The Minister of Finance yesterday announced the latest elements in the government’s overhaul of the Reserve Bank Act. As with so much of that multi-year multi-stage review it has good bits and bad bits.

I support the introduction of deposit insurance (with risk-based pricing), for second-best reasons canvassed here numerous times over the years (deposit insurance increases slightly the likelihood a big bank will be allowed to fail). I also support putting all deposit-takers under a common regulatory regime, replacing the weird halfway house we’ve had for the last decade or so where banks are under one regime and non-banks under another (with the Bank having key powers over the banks, but the Minister of Finance being responsible for key policy matters re the non-banks). So I’m not writing any more about those (well-flagged) aspects of yesterday’s announcement.

However, this – from the Minister’s press statement – was something of a bolt from the blue.

The reforms will also include a new process for setting lending restrictions, such as loan-to-value ratios.

“This will give the Minister of Finance a role in determining which types of lending the Reserve Bank is able to directly restrict. The Reserve Bank will then have full discretion to decide which instrument is best suited to use and how the restrictions are applied,” Grant Robertson said.

“As with other prudential requirements, lending standards policies will be subject to more general requirements such as consultation with other government agencies and the public, and the Reserve Bank needing to have regard to the Minister of Finance’s Financial Policy Remit.”

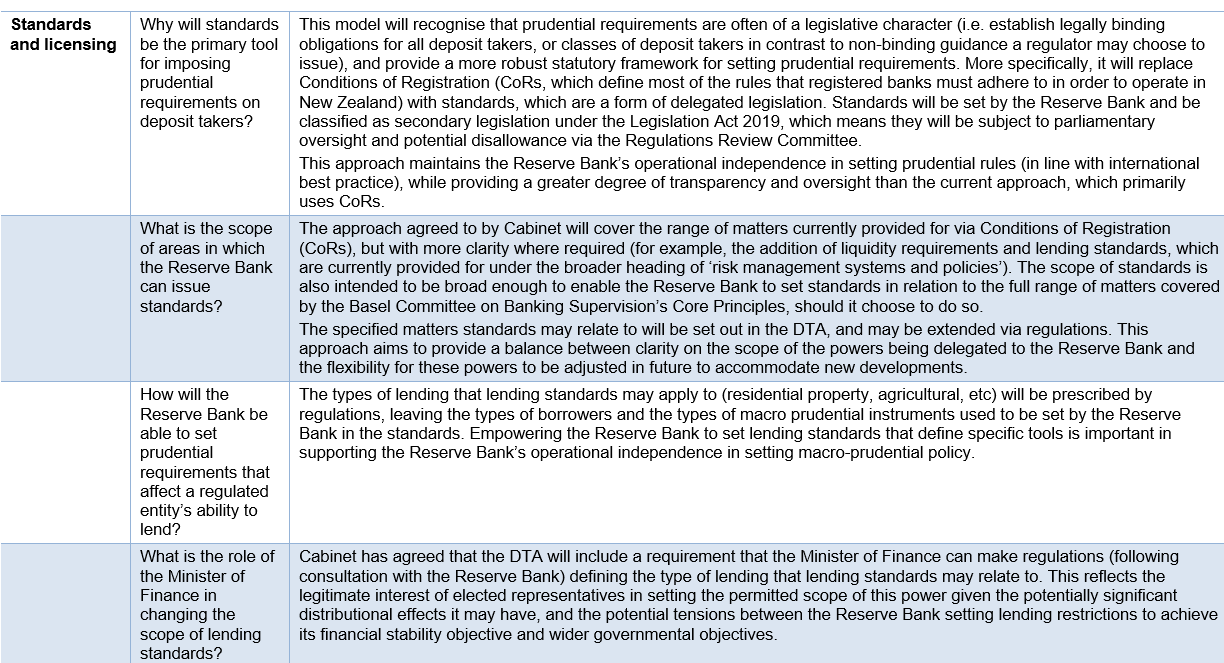

This was somewhat elaborated on in a Q&A document provided to journalists (which doesn’t seem to be on the Beehive or Treasury websites, but which one journalist sent me for my comments). The key bits are as follows (and apologies if it is a bit hard to read).

The first two rows there seem just fine, and indeed in some respects a significant step forward (notably treating future Reserve Bank prudential standards as secondary legislation, subject to proper parliamentary oversight and potential disallowance). They will also remove the current ambiguity around whether, for example, LVR restrictions are even a lawful use of existing legislation.

The problems – indeed, the oddity – is in the final two rows. Specifically

Cabinet has agreed that the DTA will include a requirement that the Minister of Finance can make regulations (following consultation with the Reserve Bank) defining the type of lending that lending standards may relate to. This reflects the legitimate interest of elected representatives in setting the permitted scope of this power given the potentially significant distributional effects it may have, and the potential tensions between the Reserve Bank setting lending restrictions to achieve its financial stability objective and wider governmental objectives.

I described this yesterday as a slightly curious step forward. It is a step forward because under the current Reserve Bank Act, applying to regulation of banks, all the policymaking powers rest exclusively with the Bank (the Governor personally at present), even though there are no clear and specific objectives, and thus little or no effective accountability. It is a really severe democratic deficit, only compounded in practice by the inadequacies of the Reserve Bank itself (see earlier posts on the weaknesses of their analysis, and the Governor’s bullying approach, around major regulatory policy initiatives).

There was an attempt some years ago to paper over this problem with the macroprudential memorandum of understanding between the Bank and the then Minister, which purported to give the Bank authority to, for example, use LVR restrictions. “Purported” because the Minister had no legal role, or authority – and could not formally stop the Bank doing what it wanted – but it may have provided some sort of political check (and without the MOU it is likely the Bank would have pressed ahead with debt to income limits).

Yesterday’s announcement appears to recognise that there was a problem, a weakness in the framework, leaving too much power in the hands of a central bank that has no mandate and no accountability. But the way the government has chosen to respond is really quite bizarre, the more so (it seems to me) the more I have reflected on it. As, frankly, are some of the other economists comments I’ve seen suggesting that this will take away the Bank’s “operational independence”.

Now, in fairness, some concerns may be allayed when the detailed legislation emerges. There are concerns that a government will be able to regulate that, say, credit to businesses they don’t like will be able to be regulated, but not that to businesses they do like, or (to take an absurd extreme) credit to National voters (or voting areas) could be restricted but not that to Labour voters. One would hope the legislation makes clear that any such regulation-making power – over which areas the Bank can impose lending standards – is subject to a clear and demanding statutory test, to ensure that such designations can be used only where there is a systemic-level threat to the financial system.

But then that is where the oddity comes in. You would expect the Reserve Bank to be (much) better positioned than ministers to determine where threats to financial stability might come from. While politicians are, in our system of government, the prime legislators and policymakers. They, after all, are the only ones we can toss out in elections, and the only ones facing day to day scrutiny and challenge in Parliament.

And yet, we are told, under this legislation the Minister of Finance will identify the risk areas (albeit “in consultation with” – but not subject to- the Bank), and then the Bank will be free to do whatever it likes in those areas. Of course, when I frame it as “the Minister of Finance will identify the risk areas”, it is also about “the Minister of Finance will identify the political no-go areas”. But that too is bizarre: the government might object to direct restrictions on lending to first-home buyers, but is unlikely to have the same objection to high capital requirements in respect of such lending – but the government can only determine the type of lending the Bank sets “standards” for, not the tools used. If there is a place for politicians in all this – and I think there is an important place – it should be about use of specific regulatory interventions (potentially very heavy-handed ones), not the identification of areas of risk.

Thus, I’ve seen no coverage of the fact that – on what we are told yesterday – in future the government will claim no right to determine whether or not debt to income limits can be imposed. That would represent a really big step back from the model the government and Reserve Bank tells us they have been using for the last decade or so. (And recall, again based on what we are told, if the government is okay with regulating housing lending – even first home owner lending – they won’t be able to (say) distinguish between LVR and DTI restrictions. That would be entirely a matter for the Bank, with no clear objectives and no effective accountability.

This is simply wrongheaded, giving official and up to date sanction to a near-unlimited potential set of regulatory interventions by an independent (and not very expert) agency. Those powers – if they are to exist at all – should rest with the Minister of Finance and Cabinet, taking advice from the Reserve Bank and Treasury.

It is also where some of the comments about “operational independence” get quite confused. As regards central banks the concept of operational independence grew up around monetary policy to distinguish the ability to adjust, say, an OCR in pursuit of a target, and the ability to set the target itself (which would be “goal autonomy”). The ECB has both goal and operational autonomy on monetary policy, but the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (like most central banks with modern legislation) has operational autonomy to pursue a target set for them by politicians. There is quite widespread support for that sort of model (even if the case is weaker than it once seemed). Not only is there a fairly clear objective and some reasonable way to assess whether or not the job is being done well, but central banks typically have quite limited (often no) direct regulatory powers as regards monetary policy: they can set their own interest rate, and can buy and sell assets (ie indirect influence), but that is about all.

By contrast, in bank (and now non-bank) regulation there is (a) no clear and specific objective, (b) no clear way of knowing whether the job is being done effectively (systemic bank failures are very rare, so there are few observations), but (c) there are few effective constraints on the direct regulatory interventions the Bank could use. It appears, for example, that they could simply ban some types of credit (provided by deposit-takers) if they so chose, or hugely impinge on household or business choices, in ways that – if done at all – should only be done by people we can hold to account. And that isn’t the Governor or the (new) Board. (As it happens, this is more or less the model – Bank advises, Ministers decides – that applies to non-bank deposit-takers, which is the reason why LVR controls don’t apply to them.)

We do want operational autonomy for the prudential regulatory agency. But that operational autonomy is about the implementation of policy powers that – at least in the broad – are set by elected policymakers. We do not want politicians interfering in how rules are applied to favour, say, one bank over another – any more than we want politicians interfering in which individuals get NZS, but the NZS policy parameters should be set by those we elect. There are grey areas (what is implementation, what is policy) but what the current government is proposing is a significant in increase in the policymaking powers of a bureaucratic agency – formally so in the case of non-banks, informally so (the prior constraint of the MOU) in respect of banks. That simply fails standard tests of good government, democratic accountability and so on – and would do even if the Reserve Bank were demonstrably an excellent agency.

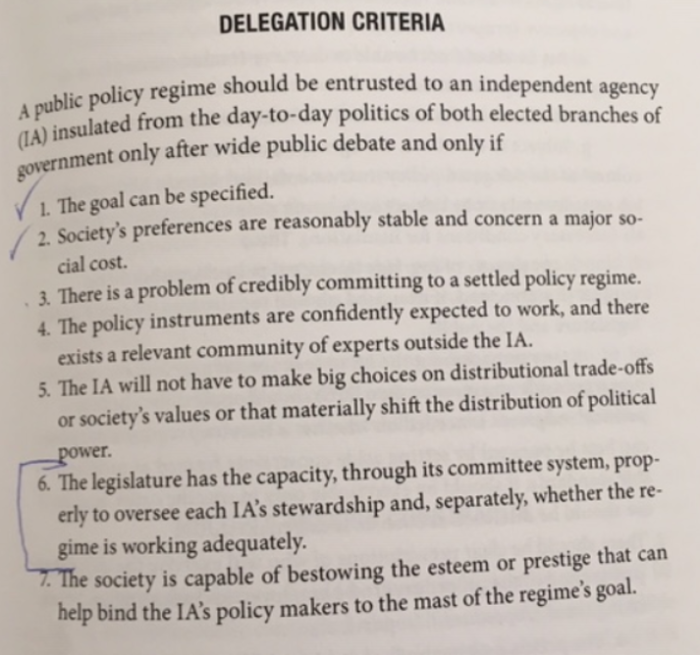

I’ve written here previously about the very useful book (Unelected Power: The Quest for Legitimacy in Central Banking and the Regulatory State) published a few years ago written by Sir Paul Tucker, former Deputy Governor of the Bank of England. This summary table is taken from the book.

Giving far-reaching policymaking powers to the Reserve Bank, particularly in areas that directly impinge on firms and households, simply does not pass the test. Cabinet seems to have rightly recognised that politicians have key responsibilities and accountabilities, and yet taken a strange – and weak – approach in response.

To be clear, I do not favour any of the sorts of interventions the Bank has adopted or tried to get introduced in recent years. The prudential regulatory (system soundness and efficiency) case for LVRs or DTIs has never been compellingly made, and if I had my way the law would prohibit either the government or the Reserve Bank from imposing such restrictions (without specific new primary legislation). But if such powers are to exist, they should be exercised only by those we elect, those we can properly scrutinise, those we can toss out.

(On which note, the government is currently advertising for members of the new Reserve Bank board, to take office in July 2022, when the Board will assume all the financial regulation powers statutes give to the Bank. The formal job description is not quite this bad, but note that in the big newspaper adverts for these roles “championing diversity and inclusion” and “sound understanding of Te Ao Maori” (even “operating with intergenerational horizons”) come before any specialist expertise in the subject matter the Bank is responsible for.)

You should have been at out meeting with the Treasury on deposit insurance for ponzi schemes in the finance companies sector.

LikeLike

Ranginui Walker said the Treaty was the countries first immigration document. As much as he is revered on the left his opinion didn’t matter where it got in front of [the] “much larger agenda for change in this country”. [Bedford]

LikeLike

wrong topic sorry

LikeLike