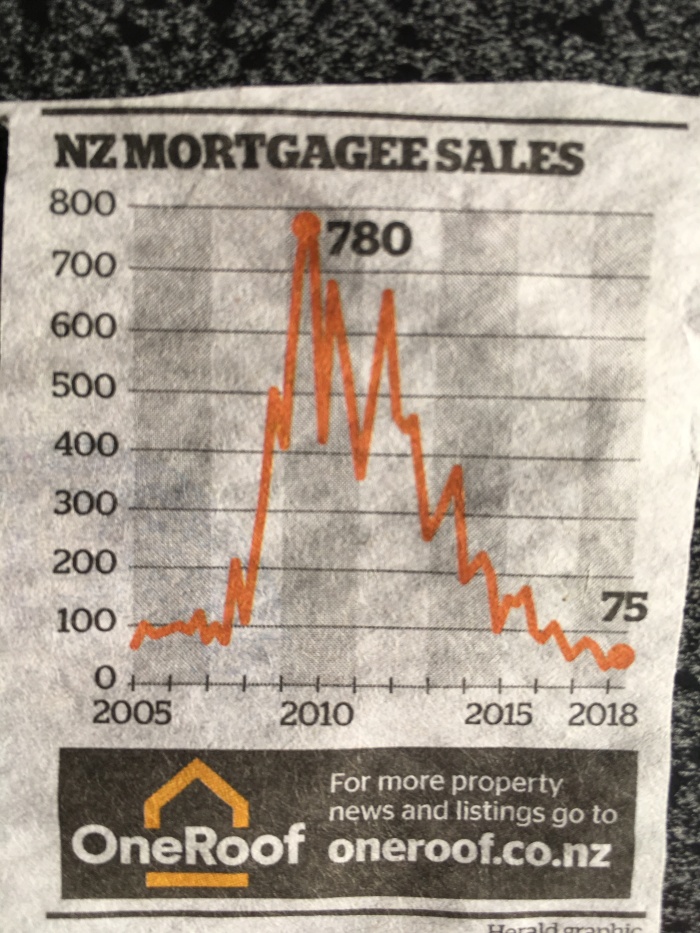

This chart appeared in an article in yesterday’s Herald, heralding (so to speak) mortgagee sales of houses hitting the lowest level for more than a decade.

The chart isn’t clearly labelled, but it appears to be quarterly data. Elsewhere in the article, it is noted that the peak in annual mortgage sales was 2616 in 2009 – the trough of the last recession, when the unemployment rate had risen quite sharply and nominal houses had fallen quite a bit (down 9 per cent nationwide in the year to March 2009).

In many respects, one wouldn’t wish a mortgagee sale on anyone. But one also wouldn’t wish any individual to find themselves overstretched and having to sell the house themselves (and thus not a mortgagee sale).

But, equally, risk is part of a market economy. And the housing stock financed by mortgage isn’t just the (sympathetic) case of the first home buyer owner-occupier, but also investment properties, beach houses, and fancy houses (the Herald story includes a piece about a pending mortgagee sale of a $3 million house in St Heliers). In a country of almost five million people (and more than 1.8 million dwellings) one might reasonably wonder whether a mere 250 to 300 mortgagee sales in an entire year is lower than might be, in some sense, entirely desirable. After all, the nature of taking risk – and both purchaser and financier do – is that sometimes things will go wrong. The optimal number of mortgagee sales is very unlikely to be anywhere near zero.

The key combination of factors that tends to drive the number of mortgagee sales sharply upwards is higher unemployment and falling nominal house prices occurring together. If unemployment rises but house prices stay high then even if the borrower runs into servicing difficulties they can usually sell the house themselves, repay the mortgage, and move on, without the additional and humiliation of being sold up by the bank. If nominal house prices fall but unemployment is still low, borrowers will typically still be able to service the debt, and banks are reluctant to sell up people with negative equity who are still servicing the debt, even though they are legally entitled to do so.

We had that combination in 2009 (although in neither case to extremes) and you can see the consequence in mortgagee sales in the chart.

What is often lost sight of is that in a properly functioning housing and urban land market, mark to market losses on houses shouldn’t be uncommon, even in nominal terms (with, say, a 2 per cent national inflation target). In such markets, land use can readily be changed in favour of housing development, and new houses/apartments readily consented and built. In such markets there is no reason to expect a trend increase in real house prices, even if the population is growing rapidly. Across a full country, some areas will do well and some not. So some localities will more often see, perhaps modest, trend falls even in nominal house prices. And, of course, without ongoing maintenance individual properties would depreciate in most localities.

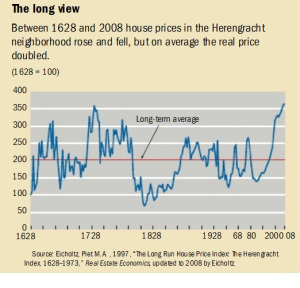

For those who doubt that such things are possible, I could bore you with charts from US cities where the markets function well, but instead I will use it as an excuse to reproduce what was for a long time one of my very favourite charts (written up here), showing prices for a street of houses in central Amsterdam from 1628.

There are ups and downs, but over several hundred years no strong trend.

And, of course, that is now what marks out housing markets in New Zealand (and Australia, and various other places, including parts of the US, where land use restrictions have become binding). In recent decades there has been a strong upward (regulation-facilitated or induced trend) in real (and even more strongly in nominal terms) house prices. As I noted yesterday, REINZ numbers show that over the last five years prices in Auckland and out of Auckland have averaged 8-9 per cent increases every year. And that was on top of substantial increases in the 1990s and the 2000s. It isn’t that easy (although not impossible) to get yourself into a position where the bank sells you up when house prices are rising that strongly. But in a well-functioning market, we wouldn’t see such pervasive trend increases.

It is interesting that the number of mortgagee sales is now lower than it was in the mid 2000s (even though the housing stock is bigger now than it was then). The unemployment rate has come down quite a long way, but is still about a full percentage point higher than it was in 2006/07 (and underemployment rates linger high). For the sort of people – a diminishing number – who can afford a house anyway now, unemployment probably isn’t a big consideration now. But, again, in a well-functioning housing market – in which the Prime Minister wasn’t doing photo-ops with professional couples who’d won the lottery to buy a subsidised four bedroom house, but appearing with a working class couple of similar age able to buy their first house in one of our larger cities – it might well matter more. Downturns hit harder people in less skilled jobs, and with more marginal attachments to the labour market. In a better functioning system, more of those sorts of people would be buying houses, and some would end up unlucky and having to sell up later. That is the “price” we pay for better access to the home ownership market.

The other relevant consideration is access to finance. If a bank won’t lend more than, say, 40 per cent of the value of the property, it would be extremely difficult to ever see a mortgagee sale (only, say, idiosnycratic shocks such as the house burning down when the borrower had forgotten to pay the insurance bill or some such). At the other extreme, of course, if banksare lending 115 per cent of the value of the property – in some over-exuberant mood in which everyone believes property values only ever go up, and where new buyers want to have extra cash for, say, fancy furniture, then it doesn’t take very much to go wrong for there to be lots of cases of negative equity, and potentially lots of mortgagee sales. Mostly – and to the credit of the banks – we’ve avoided those sorts of excesses.

But for five years now we’ve had the unprecedented situation of the Reserve Bank limiting how much banks can lend to individual purchasers of residential properties (LVR limits). We went through successive waves of these controls, and although they were eased somewhat last year binding restrictions are still in place. The economic case for these controls was never robustly made (the Bank could never quite get round the fact that its own stress tests kept showing that banks were in fine health, or that mortgage lenders – public and private – had for decades been lending 90 per cent LVR loans in New Zealand and been able to managed the associated risks).

The Reserve Bank has been keen to boast about how effective these controls were in limiting the amount of high LVR lending banks were taking on. They always presented this as “a good thing” even though they could never demonstrate (a) that banks were safer as a result (all else equal, banks need less capital when they have fewer risky loans), or (b) that their judgement on prudent lending standards was better grounded than that of willing borrowers and willing lenders, with their own money at stake, or, incidentally (c) what other risks banks might have chosen to take on to keep up profits if prevented by regulation from lending to housing borrowers.

There wasn’t much doubt, though, that LVR controls applied tightly enough – and the RB controls became increasingly tight – could restrict the amount of high LVR housing lending. And high LVR loans will be disproportionately represented among those where a mortgagee sale eventually occurs. So, even in a period of moderate unemployment, it is quite likely that LVR restrictions have reduced the number of mortgagee sales.

But it simply doesn’t follow that that is a good thing. The other side of the same equation is that some people who would otherwise have been able to purchase a property using credit, whether owner-occupiers or investors, won’t have been able to do so. Perhaps those people will have got into the market a few years later, but in the interim they will have missed out on the opportunities of home ownership – and in most localities, being forced to wait means the entry price will be higher than it would have been if Reserve Bank controls had not intervened. Those are real missed opportunities, while regulations skewed the playing field (cheaper entry levels) for cashed-up buyers.

In a well-functioning market, house prices rise and fall (although typically not that dramatically) and it is unlikely anyone will be much good at forecasting the movements that do happen. With the best will in the world, and the best countercyclical monetary policy, economies will fluctuate, and some people who’ve taken on debt will find themselves unable to service the loan. Painful as that no doubt it, it is only one of the many potential vicissitudes of life – probably not the end of the world if you are in your 20s and have decades to get back in the market. The alternative to expecting that a reasonable number of people will eventually have to sell up, in a world of uncertainty and unforecastability, is to have credit policies so tight that they also exclude substantial cohorts for much longer than necessary from being able to enter the housing market at all, whether as owner-occupiers or investors.

I don’t wish a mortgagee sale on anyone, any more than I’d wish a business failure or a redundancy on anyone. Even the transactions costs associated with any of these of events are often non-trivial. But without them – while still in a world where the future can’t be foreseen – we’d be living in an economy so cossetted that many opportunities – for individuals and for the economy as a whole – would be missed. In the housing market, between regulatory restrictions on access to housing credit and other regulatory restrictions which impart a strong upward bias to real house prices, we are probably in that sort of situation now. Too few people can get into the market at all, and too little risk may well mean we are in a position where a higher level of mortgagee sales might be desirable for the efficiency of the economy, the financial system, and the housing market itself.

Took a look at Epsom/Mt Eden properties on realestate.co.nz and there is a big pullback in the values. That foreign buyers ban is certainly affecting the values of these properties that were previously above $2 million plus pitching many now below the December 2017 Council QV valuations by many hundreds of thousands of dollars. This is in contrast with my below $1 million properties in other Auckland suburbs which seems to be quite stable and now starting to rise again.

LikeLike

A long-run, inflation-adjusted house price increase of 0.2% per year sounds pretty sweet to me. As a property owner, rampant house price increases over the short term have made me feel very lucky I got in at the right time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a lot of economists forget to factor in is that we are talking about inflation adjusted leveraged returns. For most people they start off with only 20% or less for a deposit and borrowed the rest. When inflation was running around say 10%, a 20% equity leveraged return would have been 50% even though the price increase on the property was only 10%.

As a property owner it actually does not really matter when you buy. It is not about timing the market but it is actually time in the market.

LikeLike

The main reason for the mortgage not being paid: unemployment & falling house prices? I was told that when that occurred in the UK about 1990 half the mortgagee sales were due to relationship breakup. Don’t most businesses obtain finance from their owners increasing their mortgage? If a business fails to deliver expected profits then a mortgagee sale could occur.

I think the LVR limit was a wise move; it protects two greedy groups from excess (home buyers and banks). Spent the morning reading about USA sub-prime loans pre-2008 and have concluded there does need to be some standardisation of mortgage loans sufficient to make them understandable by typical purchasers – it is only similar to the consumer protection involved in selling butter in standard weights and alcoholic drinks in standard units.

NZ is full of zombie towns and villages; they have acceptable houses, some boarded up and they have reasonable prices.

LikeLike