I’d seen various news stories suggesting that in a speech on Tuesday the Minister of Finance had made the case for sticking with the Budget Responsibility Rules agreed with the Green Party this time last year. So I thought I should read the speech. There wasn’t much there. The rules were restated, including the debt commitment, but there was no case made for following those particular rules, rather than some others. The furthest the Minister got was the standard fallback line

We must be fiscally responsible. We must ensure that New Zealand is well-placed to handle any natural disasters or economic shocks.

Which doesn’t help, because it doesn’t differentiate the Minister’s rules from those of any other reasonably conceivable alternative. Resilience to natural disasters or economic shocks is the fiscal equivalent of a motherhood and apple pie standard.

In terms of the government’s self-imposed fiscal rules, the only one that really troubles me is the debt one. There are also these two

We will deliver a sustainable operating surplus across an economic cycle.

and

We will maintain Government expenditure within the recent historical range of spending to GDP, which has averaged around 30 percent over the last 20 years.

But what of debt

We will reduce the level of net core Crown debt to 20 percent of GDP within five years of taking office.

In general, debt targets – with relatively short time horizons to achieve them – aren’t very sensible as operational rules. Such a rule can mean that a few fairly small, essentially random, forecasting errors in the same direction can cumulate to produce a need for quite a bit of (perhaps unnecessary) adjustments to spending or revenue. More seriously, recessions can throw things badly off course for a while, and risk pushing a government into a corner – either abandon the target just as debt is rising, or fallback on pro-cyclical (recession exacerbating) fiscal adjustments – even though, in across-the-cycle terms, the government’s finances might be just fine. No one looks forward to a recession, but governments (and central banks) need to work on the likelihood that another will be along before too long. Natural disasters – the other shock the Minister mentioned – can have the same effect.

Personally, I would be much more comfortable with only two key quantitative fiscal rules:

- a commitment to maintaining the operating balance in modest surplus, once allowance is made for the state of the economic cycle (cyclical adjustment in other words) and for extraordinary one-off items (eg serious natural disasters), and

- something about size of government. Simply as an economist I don’t have a strong view on what the number should be, although as I’ve noted previously it is curious that the current left-wing government, arguing all sorts of past underspends, was elected on a fiscal plan that promised spending as a share of GDP that undershot their own medium-term benchmark (that around 30 per cent of GDP).

The suggested fiscal surplus rule isn’t an ironclad protection (any more than a real-world inflation target in a Policy Targets Agreement is). There are uncertainties about the state of the cycle and how best to do the cyclical adjustment, and incentives to try to game what might be counted as an “extraordinary one-off”. That is why the fiscal numbers and Budget plans will always need scrutinising and challenging. But if followed, more or less, such a rule would be sufficient to see debt/GDP ratios typically falling in normal times, and to avoid things going badly wrong over a period of several decades. That is probably about as much as one can realistically hope for.

There are those arguing for the government to increase its debt levels at present. I’m a bit sceptical of that notion, for several reasons. The quality of a lot of government capital spending – whether it is cycleways, trains, or roads, just to take the transport area – often leaves a great deal to be desired. Advocates of more debt often talk up the relatively low interest rates at present, and suggest those low rates offer great opportunities. Except that when interest rates have been low – and if anything still falling – for a decade, they probably need to be treated as semi-permanent, and thus as revealing something about the perceived economic opportunities advanced economies are offering. And – a point I’ve made often – low as our interest rates are by historical standards, they are still high by the standards of most other advanced economies.

One consideration that might suggest it would be sensible for New Zealand to run higher debt than most other advanced countries is that our population (boosted by immigration policy) is growing much more rapidly than those of most other advanced countries. All else equal, that should lead to faster growth in future GDP (not GDP per capita, just the total) and future tax revenue, suggesting more capacity to carry debt now. There is certainly something to that argument at the local level, and hence I hope the government’s talk of facilitating local authority SPVs, which will enable debt to be taken on, serviced by specific property owners’ future rates commitments but outside existing core local authority debt limits, comes to something. I’m much more sceptical of the story at the national level since on the one hand champions of immigration will stress the idea of immigration providing immediate fiscal gains (a claim there is probably something to, even if – as Fry and Wilson suggest – those effects die away over time). If there is really an upfront windfall, there shouldn’t need to be more debt taken on. And, on the other hand, for whatever reason, New Zealand’s trend productivity growth rate has been lousy for a long time, suggesting that even if our numbers (of people) are growing faster than in other countries, our (total) GDP won’t be that much faster. It would be a different story if, say, more people was transforming (lifting sharply) our productivity performance, and future incomes, but there isn’t much sign of that.

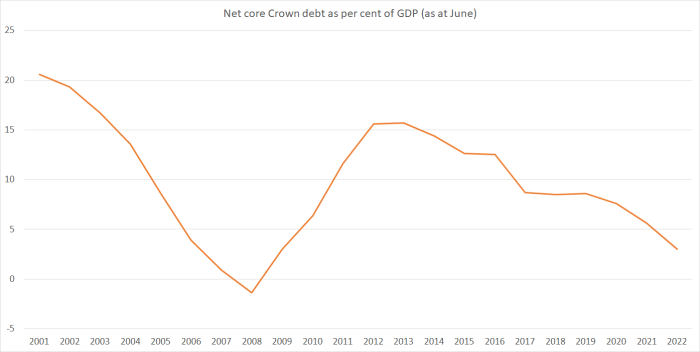

What about some numbers/pictures. Here is a chart (including Treasury forecasts) of core Crown net debt as a per cent of GDP. This isn’t the variable the government (and its predecessor) choose to target, since it excludes assets held in the New Zealand Superannuation Fund. But it is all just money, and NZSF assets could be liquidated in quite short order if necessary. (Even this variables excludes some government on-lending (“advances” in Treasury parlance) which seem to be about 5 per cent of GDP).

After a serious recession and a weak recovery, and a series of pretty costly natural disasters, this measure of net debt peaked at a level lower than we’d had a decade earlier. The estimate for June 2018 (from HYEFU numbers) is debt of 8.5 per cent of GDP. On current plans – as communicated by the government to Treasury – debt would drop away to 3 per cent of GDP by 2022. At that point, it wouldn’t be quite as low as the 2007 or 2008 levels – reached after a sequence of huge, unexpectedly large, and economically unnecessary surpluses, and partly reflecting a prolonged expansion in which the economt ran ahead of medium-term capacity – but it would be pretty close.

There is no easy metric for what an appropriate level of government debt is. And the agency issues around government debt are much more severe than those for private debt – governments aren’t spending their own money. The parallels here aren’t exact either, but a typical middle-aged household is likely to have debt materially higher than 3 per cent – or even 8 per cent – of their GDP.

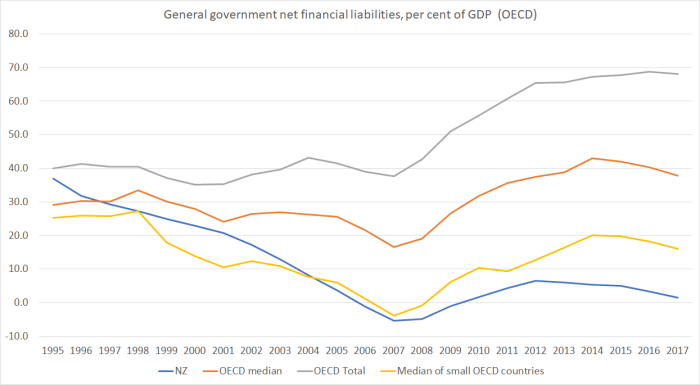

What about some cross-country comparisons? Here I turn to the OECD and, in particular, their series on general government (ie not just central) net financial liabilities. I start from 1995, because that is when the OECD has data for almost all countries.

I thought there were a couple of interesting points here:

- for all the talk of governments piling on debt since the 2008/09 recession, net debt in the median OECD country (orange line) last year wasn’t materially higher than it had been 20 years previously,

- but total net debt over all the OECD countries (the grey line) has increased very substantially. Of the big OECD economies – US, Japan, Germany, France, Italy, UK – only Germany doesn’t have a much higher debt ratio now than in 1995.

- small OECD countries seem to have been much more conservative in managing their public debt (yellow line). That group includes – at one extreme – Greece and – at the other – Norway. The median net debt of those countries is materially above where it was in 2007, but it isn’t much different than it was in, say, 2002 (15 years earlier).

New Zealand doesn’t have the lowest net debt by any means (Norway has net financial assets of 280 per cent of GDP). In fact, we mark out something around the lower quartile. We’ve had some disadvantages the other small countries didn’t – earthquakes – but on the other hand we’ve had an unusually strong terms of trade and weren’t constrained (as many of them were) by being in the euro. But it looks hard to make a strong case for actively pursuing lower net debt from here. It isn’t as if, for example, there is any sign of the economy overheating.

(Things not shown are often as important as those shown. Unlike many of the more indebted countries, we do not have a large unfunded pension liability for public servants in New Zealand. Those liabilities are not included in these debt numbers.)

Feckless governments in other countries don’t necessarily make for much of a benchmark. And, as above, I’m not actively calling for New Zealand governments to take on more debt. But simply producing a sequence of modest cyclically-adjusted operating surpluses (NOT several per cent of GDP) over the next few budgets would seem to be about as much as it would be sensible – from a macroeconomic perspective – to ask from a government.

And, on a final note, I am increasingly uneasy about one aspect of the Labour-Greens budget responsibility pledges that seems to have disappeared almost totally.

This was the promise

-

The credibility of our Budget Responsibility Rules requires a mechanism that makes the government accountable. Independent oversight will provide the public with confidence that the government is sticking to the rules.

-

We will establish a body independent of Ministers of the Crown who will be responsible for determining if these rules are being met. The body will also have oversight of government economic and fiscal forecasts, shall provide an independent assessment of government forecasts to the public, and will cost policies of opposition parties.

But nothing more has been heard. I wrote about it here, and suggested that the idea should be broadened to become a Macroeconomic Advisory Council. That still seems sensible to me, especially as the Reserve Bank reforms the Minister has announced to date do nothing to strengthen effective scrutiny of the Reserve Bank. But for now, it would be good if the Minister could update us on what has happened to the Fiscal Council promise.

I favour tight fiscal policy for NZ as we are a savings-short country, so if we were to spend up on infrastructure (say) by running fiscal deficits, it would put a lot of upward pressure on the exchange rate. Of course this is not to say that fiscal policy by itself can generate an adequate level of savings as we saw in the Cullen years

LikeLike

NZ Household savings is currently $170 billion plus Kiwisaver $60 billion against NZ household housing debt of $175 billion. How is that a savings short country?

LikeLike

If you then balance that $175 billion NZ household house debt plus $60 billion in residential investment property debt against a trillion dollars in Residential Property value then the scale of the lack of debt against NZ household house assets is quite apparently very low.

LikeLike

What gives money and kiwi saver value if house prices collaps? Lucky I won’t starve because I have money under the bed that has a store of value not connected to asset inflation.

LikeLike

Money is not a store of value as it is just a piece of paper and digits on a computer screen. It is a medium of Exchange created by the community and pretty much is an untangible value supported by just confidence. If you are unaware, India recently punished people storing their cash under their beds. So they put in a law to change the currency. Overnight your wealth disappears because it is no longer a medium of exchange it just becomes pretty pictures on paper.

Houses have underlying support as it is supply restricted and people need somewhere to live. There is therefore a fundamental support for that value. A good analoy is It is an exclusive club with a life time membership ie wait for someone to die then a new person can get membership or pay the owner the price he is prepared to exit and for a new member to enter that exclusive club. The only solution is to build more but land constraints and a growing population prevent that.

LikeLike

Usually only around 8% of Kiwisaver funds are typically invested in usually Commercial Property. Pehaps some of it through Fletcher in the building sector. Therefore house value has very little significance to Kiwisaver.

LikeLike

Blair, the NZD is the 10th most heavily traded currency in the world with $500 million to a billion traded every single day of a year. Export GDP which is a small part of that accounts for $60 billion of that. NZ overseas bonds issued is around $70 billion which has been relatively stable. The impact to the exchange rate would be the interest payments around 3% per annum of the $70 billion plus any increments to the level of overseas borrowing which equates to hardly any impact to be able to shift sentiment in the NZD.

LikeLike

Thank you for this blog post.

It could well do something to counter the deficit hysteria that seems to pervade mainstream public discourse on “fiscal responsibility”.

LikeLike

One query :”governments aren’t spending their own money.” What about Japan? The Bank of Japan buys a whole lot of its own government’s debt overtly with little inflationary consequence. Or is that not the case?

Be interested in your take on this.

LikeLike

The agency issues are still much the same – they are using levers of govt to make choices affecting others, and not at cost to themselves (unlike, say, you or me with a mortgage).

I’m a little sceptical that the BOJ bond-buying has made a great deal of macro difference – certainly not enough for the BOJ to meet its inflation target. With interest rates near or below zero, that isn’t overly surprising – which asset banks hold (bonds or accounts at the BOJ) is less important than it used to be. That said, from an employment perspective it is hard to make a case for the BOJ to do more – the unemployment rate is materially lower than (for example) our own.

LikeLike

Michael is it possible to grow the economy if there was zero house price inflation for 10 years? Japan used credit guidence from 1947 to 1984.

LikeLike

yes, indeed it is. After all, check out those fast-growing swathes of middle America, where real house prices haven’t changed much in 30 years. House price inflation itself is no engine of growth (it probably boosts the spending of some, and dampens that of others – for whom a house is further out of reach), but mostly just a reflection of some structural imbalances (land regulation and immigration policy). that isn’t to say that a sharp drop in house prices wouldn’t pose challenges – especially for some individuals. Economic restructuring always does, and there is a case for support/compensation for the losers in some cases.

LikeLike

Michael, I suggest you look at the Treasury’s long-term fiscal sustainability statement. Best regards, John

LikeLike

Thanks John. I’m not sure quite what aspect you had in mind (I wrote about the LTFS when it came out). I’m certainly not suggesting NZ has no future fiscal challenges – and personally think the failure to act on (eg) the NZS age is a fiscal and moral disgrace – but we don’t have some of the specific big risks many other OECD govts do in the form of public service pensions.

And altho there are some big challenges ahead to keep debt down, my real point yesterday was simply that there doesn’t seem a strong case for actively striving to lower net Crown debt below the 8% or so it is at present.

LikeLike

For office workers, 65 is probably still young but for heavy lifters and manual hard labour, 65 is already very old. In order to make NZS more viable, the 10 year stand down period must apply to the 600,000 Kiwis living in Australia that do not pay NZ taxes but are eligible for NZS. If Australia gets any tougher on its National super, we will see significant numbers of Kiwi oldies returning to NZ for retirement income.

LikeLike