Earlier in the week I wrote about Reserve Bank chief economist John McDermott’s rather strange attempt to distract attention from the Bank’s own GDP forecasts – which some had suggested were a bit optimistic – by suggesting that private bank economists didn’t understand the process the Reserve Bank used, and even using the word “nonsense” in an attempt to bat away what seemed like quite legitimate questions. Somewhat to my (pleasant) surprise, Westpac – one of the banks that had questioned the Reserve Bank’s forecasts – actually went public in response , although being an institution regulated by the Reserve Bank they still seemed to feel the need to express due deference to the powerful, ending their note this way, (emphasis added)

We are comfortable respectfully maintaining that difference of opinion.

After each Monetary Policy Statement the Reserve Bank’s senior staff fan out across the country to do a series of post-MPS presentations (I used to do some of them myself). These events are all hosted, and paid for, by the commercial banks, and commercial clients of those banks are the invited guests. It is an arrangement that is convenient for the Reserve Bank – the banks rustle up an audience – but which has always seemed a bit questionable to me: preferential access to senior public officials, on sensitive policy issues, for the invited clients of particular banks. The tone and thrust of questioning might be a little different if some such occasions were hosted by the Salvation Army or unemployed worker advocacy groups.

These occasions are supposed to be off-the-record, whatever that means. The Bank defends it on the basis that it is supposed to let them speak more freely. But the reason people turn up is to garner information and perspectives from – and ask questions of – senior public officials. And no one supposes that financial markets people in the room don’t (a) use, and (b) pass on to clients anything interesting, any different angles, that are raised when the Governor (in particular) and his leading offsiders are talking. As I’ve noted previously, the contrast with the Reserve Bank of Australia is striking: senior officials will give speeches to private audiences, but the standard practice is, wherever possible, to post the text of the address and a webcast or audio of the address and any question and answer sessions, to minimise the extent to which some have access to Reserve Bank information/views others don’t have.

After my post the other day, a reader who had been at the post-MPS presentation John McDermott had given last Friday got in touch to pass on some of what McDermott had said there. My reader felt – and based on his report I agree – that they didn’t put this senior official, or the Reserve Bank, in a particularly good light. The reports are secondhand (ie I wasn’t there), so I’m relying on my reader to have captured the thrust of what McDermott said reasonably accurately. But having worked closely with McDermott in the past, what I read had a ring of authenticity to it. My reader has given me explicit permission to quote from the email I was sent.

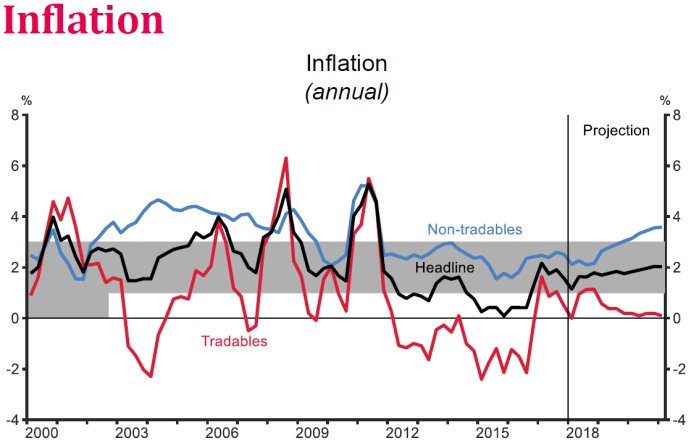

He spent the first five minutes of his short presentation defending their record by displaying a chart showing CPI, broken down into tradables and non-tradables components, over the last 50 years or so. Essentially he was highlighting how insignificant the recent deviations from target look when you compare it to the extreme volatility in prior, pre-OCR, decades. He also claimed the RBNZ can only influence the non-tradables component and was rather self-congratulatory in how well they had done there.

Something didn’t sound quite right about that (the tradables vs non-tradables breakdown doesn’t go back that far), so I asked the Bank for a copy of McDermott’s slides (which, legally required to respond as soon as reasonably practicable, they supplied within 24 hours). In fact, this paragraph was summarising two slides. The first is, from memory, one of McDermott’s favourites.

In the 70s and 80s inflation was very high and volatile, and for the last 25+ years it hasn’t been. It is a worthwhile point to make from time to time, but doesn’t have much bearing on anything to do with how monetary policy should be run right now (a bit looser, a bit tighter or whatever). Apart from anything else, almost every advanced country could show a similar, more or less dramatic, chart. And in the earlier decades, inflation wasn’t being targeted – until 1985 the ‘nominal anchor” was the (more or less) fixed exchange rate.

The second chart was this one

This is presumably what McDermott was talking about when, as my reader reported,

He also claimed the RBNZ can only influence the non-tradables component and was rather self-congratulatory in how well they had done there.

There is no doubt that, in the short-term, the Reserve Bank is a pretty minor influence on tradables inflation, which is thrown round quite a bit, and most obviously, by fluctuations in petrol prices (changes in which closely track international oil prices) and the influence of weather events of fresh food prices. The Reserve Bank can’t do much about those, and is specifically instructed (in every PTA) not to focus on them. Of course, in the very short-term the Reserve Bank can’t do much about non-tradables inflation either – it is quite persistent (ie not very volatile), and inflation right now is a response to monetary policy choices from perhaps 18 months ago, and economic forces (often hard to forecast) from the last year or so.

But it would be nonsense to suggest (if in fact McDermott did) either that tradables inflation is outside the Bank’s influence, or that the track record on non-tradables inflation is just fine. New Zealand can’t do anything much about the world price of tradables, but monetary policy is a direct influence on the exchange rate, and thus on the New Zealand dollar price of tradables. That can’t sensibly produce a stable tradables inflation rate quarter to quarter, but it can (and does) have a material influence on the trend – “core tradables inflation” if you like. And McDermott’s chart seems deliberately designed to avoid focus on the fact that, over time, tradables tend to inflate less rapidly than non-tradables. As I’ve noted previously, the rule of thumb around the Bank used to be that if one was targeting 2 per cent inflation, that might typically involve something nearer 1 per cent tradables inflation and something nearer 3 per cent non-tradables inflation.

As it happens, the Reserve Bank produces estimates (from its sectoral factor model) of core tradables and core non-tradables inflation. I ran this chart of those data a few weeks ago

Not only is this estimate of core tradables inflation not terribly volatile, but the gap between the two series isn’t unusually large or small. Overall (core) inflation has simply been too low to be consistent with the target set for the Reserve Bank. There isn’t anything for current Reserve Bank management to be proud of.

One of the reforms the new government is promising is the addition of some sort of employment objective (non-numerical) to the Bank’s statutory monetary policy responsibilities. We don’t know the details, and probably neither does the Bank – The Treasury was accepting submissions on that point right up to today – but I presume we will get a hint when the Policy Targets Agreement with the new Governor (under existing legislation) is signed and released next month. But it is an obvious area of interest and apparently McDermott was asked some questions about the new environment. You may recall that in the MPS the Bank released, for the first time, an estimate of the NAIRU (the estimated rate of unemployment at which there is neither upward nor downward pressure on inflation from the labour market) – “released”, but in a footnote (repeated in the press conference), citing analysis in an as-yet-unpublished research paper.

My reader reports that McDermott was asked about this, including

whether their estimate of NAIRU came about as a result of the likely addition of an employment mandate to the PTA, and … how they went about coming up with that number. His initial reply was “I’ve got a lot of very smart people working for me” and then he went on to basically say that the analysis and maths involved are too complicated for us to understand. He also highlighted, to the point of seeming rather proud of, the fact his team had decided to come up with the estimate on their own accord without any suggestion from him. It didn’t seem to me that even he knew how they came up with 4.7%, nor that he particularly cared much.

The final sentence is clearly editorial in nature, and may or may not represent McDermott’s actual view, although it was clearly how he came across to this particular member of his audience. As for the rest, when you put out a number in a footnote, don’t simultaneously make available the workings and background research, fall back on “very smart” staff, and won’t even attempt to explain the intuition of the work that has been done, it isn’t a particularly good look from a senior public servant. (I’ve also heard that in fact the “acting Governor” had been all over staff, as a matter of urgency, to produce publishable estimates of the NAIRU.)

I’m still looking forward to seeing the research paper when they finally get round to publishing it. Perhaps the 4.7 per cent estimate of the NAIRU (with confidence bands) will prove to be robust, although it seems implausibly high to me. But it is worth remembering that the Bank has form when it comes to rushing out new labour market indicators in high profile documents endorsed by senior managers, that play down any notion of ongoing excess capacity, without having first adequately road-tested and socialised the background research. Persevering readers may recall the saga of LUCI , touted a couple of years ago by a Deputy Governor as the latest great thing, allegedly demonstrating that the labour market was already at or beyond capacity (and at least in that case the associated Analytical Note had already been published), before the interpretation of the whole indicator was quietly changed, and then it disappeared from view.

The questioner of McDermott apparently continued and

….suggested NAIRU will presumably become a more important consideration for the Bank going forward if they are handed a ‘full-employment’ mandate but he didn’t really address that question and instead spent 5 minutes explaining why it would need to be the Bank, and not politicians, who define what full-employment means at any given time, a suggestion I wasn’t aware anyone had made otherwise. He pressed the point that he didn’t believe the change to the mandate would make any difference whatsoever and sarcastically pointed out that they already consider employment when making decisions.

Since neither we, nor McDermott, has seen the new mandate, and since the new Governor (not yet in office) will be the single legal decisionmaker for a time, and then the new statutory Monetary Policy Committee will take responsibility, it isn’t clear how or why McDermott thinks he can say with any confidence that a new mandate won’t make any difference to policy. Perhaps he wishes it to be so, but then he has been one of key figures in the regime of the last six-plus years that has delivered core inflation consistently below target even while (even on their own estimates) the unemployment rate has been above the NAIRU for almost the whole of that time. As reported, it didn’t seem a very politically shrewd answer either – it is one thing to emphasise that (as everyone agrees) in the long-run monetary policy can only influence nominal things (price levels, inflation rates etc), and quite another to suggest that there aren’t legitimately different short-run reaction functions.

We deserve better from our operationally independent central bank. Lifting the quality, and authority, of the Bank’s work around monetary policy will be one of the challenges for the new Governor, and needs to be borne in mind too by those devising the details of the new Reserve Bank legislation.

Hi Michael. The RBNZ’s release of their NAIRU estimate contrasts with the RBA’s transparent and detailed release of their thoughts on NAIRU recently. In the June 2017 Bulletin they laid out their modelling and estimates in some detail – with a very wide +/-1% 70% confidence band around the 5% central estimate. This week Assistant Governor Luci Ellis spoke on the topic. http://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2018/sp-ag-2018-02-13.html. Historically, the RBA has been reluctant to refer to the NAIRU – one official told me recently NAIRU was the concept that could not be named inside Martin Place. NAIRU is certainly a politically awkward concept for a central bank that also has a full-employment objective – saying the unemployment rate has gone as low as we’ll allow it doesn’t sound as appealing as saying we’ve achieved “full employment”. Why the change of heart? Two reasons i suspect: 1) at the moment NAIRU is a very useful device to highlight your uncertainty about the capacity/wage dynamic – both the Bulletin article and Ellis this week have highlighted their uncertainty of where NAIRU is rather than putting a lot of weight on the central estimate as a policy trigger; and 2) with NAIRU falling it’s a much easier political sell. Peter

LikeLike

This blogsite has two appeals: the clarity and courtesy of the prose and secondly the new concepts for a layman.

As an example of the former “”The final sentence is clearly editorial in nature, and may or may not represent McDermott’s actual view, although it was clearly how he came across to this particular member of his audience. “” might be paraphrased in normal conversation as “clueless”.

The concept of NAIRU was new to me before finding this website. The underlying concept that unemployment can never reach zero was obvious enough when growing up in the UK with endemic wage inflation in the seventies. I have to consider specific examples to hold the idea in mind.

Our hospitals will always need nurses willing to work nights; if they are not available then hospitals have to raise wages (or persuade INZ to grant 3rd world foreign nurses work visas). The point is nurses are available but their objection to anti-social hours can vary; why would any single person want to destroy their social life or married person want to endanger their family life. So it is quite possible that a night nurse may add to wage inflation but the same nurse working normal social hours will not.

Then consider building labourers in Auckland today; just not enough of them so presumably if you need some you have to outbid other potential employers and wages are going up (lucky for my son). However a similar level of skill may be required to do manual work in forestry and there may be forests that become viable to harvest; it could just be a matter of luck if your forest is in an area of high rural unemployment.

So location and skill level makes a difference. So do benefits; my unemployed daughter can choose to work or study or stay on benefit; her decision depends on many factors with potential wages only one.

LikeLike

I have spent the last 4 months visiting my mum in Auckland hospital. There is really only a few qualified nurses on each floor and perhaps 1 qualified doctor somewhere at night on each floor or section/department whom I have never met as i visit around 7pm each nite to spend around 2 hours before leaving around 9pm The rest of the staff are mainly interns, intern doctors or intern nurses. Many of them are international students assigned from the different study institutions and work to complete their study program.

LikeLike

Should you enquire you will find most of the top-flight medical specialists at any hospital are on an evening call-out stand-by roster for emergencies – the duty doctor will always phone the rostered on specialist for to discuss any emergency and seek guidance if necessary – usually the roster schedule for each specialist is 1 week in every 4 to 6 weeks – it’s fully covered – relax

LikeLike

From what I can see, a large part of a wannabe nurse’s job is cleaning men and women. The smell of human waste is a daily part of that cleaning job. Just make sure she would be up for all the cleaning if she wants to embark on this job.

LikeLike

Just to be clear, re the “clueless” observation, that that isn’t my view. I stepped around the wording delicately mostly because i’m always a bit uneasy about relying on secondhand reports. It possible that McDermott, if asked for his recollections would say something along the lines of “no, what I actually said was [x…]”, something subtly different in emphasis. But for practical purposes I assume my correspondent was faithfully reporting what he heard (and am grateful for his account).

LikeLike

“it is one thing to emphasise that (as everyone agrees) in the long-run monetary policy can only influence nominal things (price levels, inflation rates etc)”

I don’t think you can take it as given that everybody agrees on that point. Some quite well known economists don’t agree about that assumption at all.

https://larspsyll.wordpress.com/2017/04/22/keynes-on-money-neutrality-and-the-classical-dichotomy/

Its also relevant that even in a pure mathematical theory equilibrium can only be guaranteed to be reached over an infinite time horizon. Things which take infinitely long to happen, never do happen, and therefore don’t exist e.g the economy doesn’t have a long-run.

LikeLike

without engaging in much of a debate, let me just narrow the point to what I was really focused on – all those in current debates about NZ mon policy (Robertson, Wheeler, bank econoimsts, McDermott, Spencer, Orr, me etc) think that in the longer-run monetary policy won’t make any material or predictable difference to real outcomes. The disputes/debates are about the short-term choices/tradeoffs which, equally, everyone recognises exist.

LikeLike

Even on those narrow terms this should be highly contentious (and therefore requiring significant empirical evidence to back it up as a theory).

Here is a talk by Steve Keen discussing a fallacy in free trade theory.

At the end he highlights the persistent high exchange rate of the pound and the UK’s low investment rate (in contrast to Germany). The low investment rate will have contributed to the UK economies long term economic performance. Its also pretty well known that Germany has a history of benefiting from a low exchange rate relative to their export performance.

While the magnitude of the exchange rate effects on over all investment is debatable (and there are many other factors) the effect of monetary policy choices on the exchange rate is not. Over long time frames the exchange rate (and other direct monetary policy effects) have on going impacts on the development of the NZ economy and its eventual performance. This includes things such as available economic capacity which will eventually have impacts on inflation rates. Simply put the state of the economy is a product of its history of development and can never be de-coupled from that history.

Though of course another way of thinking about it is that the long term is so far ahead its totally irrelevant (or even so far ahead it never happens). In that sense you are of course totally correct.

LikeLike

I certainly agree that protracted real exch rate deviations have real consequences (it is at the heart of my argument about NZ economic performance) but I’d argue that those longer-term deviations (eg lasting more than 5 years) are rarely if ever caused by monetary policy (but about real savings and investment choices/preferences.

But – because i don’t have time for a long debate – my point was still narrower: it wasn’t whether long-run money neutrality actually holds, just that among those engaged in the current mon pol debates in NZ it is the standard working hypothesis.

LikeLike

Tell that to the long suffering Christchurch residents who still have tilted houses and damaged infrastructure that the poor decisions by the RBNZ in not recognising when a QE was absolutely necessary after a major earthquake that decimated a major city central. EQC just was not sufficiently funded to act urgently and to be responsive without being sufficiently funded. Instead the RB was trying to raise interest rates. We are still living with the long term legacy of those poor decisions.

LikeLike

Sounds like either McDermott realises his record is on shaky ground and has not yet ‘managed’ the politics around new Governor. Comes across at first, in the account, as defensive. The latter portion sounds like McDermoot is an ivory tower arrogant academic. I took Westpac Stephens’ ‘respectfully agree to disagree’ comment not as supplication to the RBNZ but more as choosing not engaging in power struggle…just simply being respectful. Something we should all expect of the RBNZ, as a servant of the public.

LikeLike

On reflection, i think you are largely right about the Westpac comment. as much as anything it might have been drawing a quiet contrast between the RB/McDermott style and that of Westpac’s own response.

LikeLike