Most local councils don’t employ economists – or at least not ones we hear of. The Auckland Council does have an economics unit, and the previous incumbent did some interesting and stimulating work.

But yesterday on interest.co.nz there appeared an article by two of the Auckland Council’s economists which argued, so the headline proclaimed, that “evidence from across NZ supports conclusion that land use regulation is unlikely to be the main culprit for house price rises”. They even had an estimated empirical model in an attempt to back their claim.

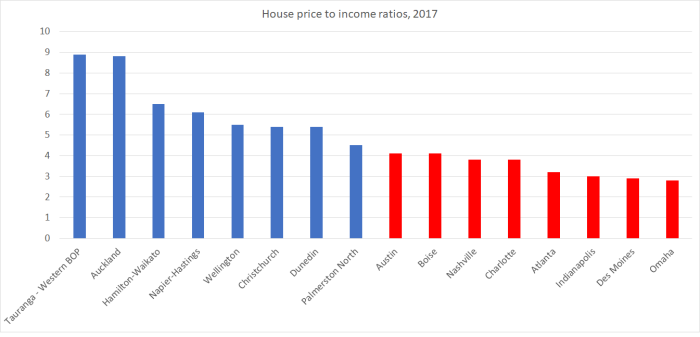

But, frankly, it looks like an attempt to play distraction, and shift responsibility from their employer (and other local governments around the country). And it is as if this is the very first time they had come to the subject and were, thus, unaware of the large number of thriving growing cities in the US with house price to income ratios not much more than a third of those in Auckland or Tauranga.

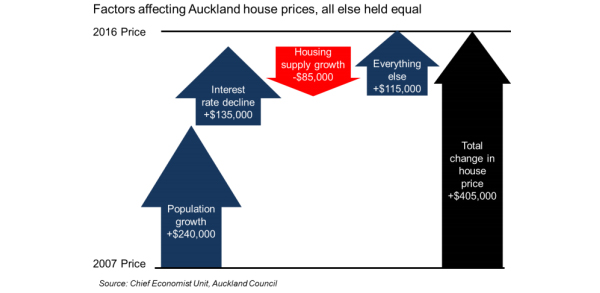

This is the centrepiece of the article

Which might look superficially fine, at least until one stops to think about what is going on here.

Firstly, it appears to be an odd model, in that they appear to be explaining changes in nominal house prices, but without any explanatory variables like general prices or wages. Over the best part of a decade, one might expect nominal house prices to rise by around 20 per cent as general costs and prices rose. Perhaps they’ve estimated the model in real terms, but there is no suggestion in the article that they have done so.

Secondly, all else equal, lower real interest rates might indeed tend to raise the value of an asset in fixed supply. But, on the one hand, this proposition doesn’t engage at all with the reasons why real interest rates might have fallen. If, for example, expected future income growth has fallen at the same time – a part of the story in most explanations of the last decade – any such asset price effect will be greatly weakened. And, on the other hand, in a well-functioning housing and land market, the only fixed factor here is unimproved land. And absent land-use restrictions, unimproved land in most places – even most parts of a city – simply isn’t worth much. Perhaps you might think of $50000 per hectare for good rural land. You could see long-term real interest rates fall 300 basis points (more than we’ve actually experienced), with no changes in future income expectations, and it still wouldn’t make that much difference to the free-market price of unimproved land (and the component of that used in a typical suburban dwelling).

Third, what about population increases? Auckland (and Hamilton and Tauranga) have had a lot of population growth – indeed, over decades Auckland has had one of the fastest population growth rates of any largest city in an OECD country. And when regulatory obstacles – land, consenting/construction or whatever – get in the way then shocks to population will boost house prices. There are regular population estimates published, which are easy to drop into a model. And, no doubt, had Auckland’s population growth rate been half the actual rate, house and land prices would be somewhat lower. But all this simply ignores the point – the insight we really get from that swathe of US cities, (as well, actually, as from basic theory) – that population growth alone makes little or no sustained difference to house prices when the land and construction markets are free to work effectively. So ascribing responsibility for house price increases to population growth is largely just cover for the regulatory failures of central and local government.

As a reminder, in fairly substantial US cities – with growing populations – we find median house (including land) prices of around NZ$250000 to $300000 (from the Demographia report: Des Moines US$198000, Louisville US$176000, Omaha $179000).

Noting that across local authority regions places with larger population growth rates have tended to have higher house price inflation, the Auckland City economists attempt to cover themselves this way

To point the finger at land use regulation would imply that all the areas with the largest population increases have the worst land use regulations and those with the smallest gains have the best regulations.

But that simply doesn’t follow. Of course, it is often the interaction between population pressures and land-use restrictions that matters in determining what happens to prices. And it is quite plausible that places with the fastest population growth might even have some of the less worse land-use restrictions, but those restrictions are simply placed under more pressure. Land-use restriction is, to some extent, endogenous.

As the end of their article approaches, they argue that

Council, the Reserve Bank and the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment have all estimated Auckland’s housing shortfall at between 43,000 and 55,000 and growing. The Auckland Unitary Plan allows for up to one million potential new dwellings. Yet the plan was implemented a year ago, and there is no evidence of decreasing land prices.

Put another way: If having already zoned to develop 20 times the current housing shortfall is not bringing land prices down at all, can land use regulation in Auckland be the major cause of high house prices?

As I’ve noted here previously, those estimates of a “housing shortfall” are almost meaningless. In the Auckland market as it stands, given the regulatory and other features, effective supply and effective demand appear to be in more–or-less balance. What makes me say that? The fact that prices haven’t moved much for a year or more. No doubt there would be demand for many more houses if the price of land were lower, but at current land prices – regulated and thus artificially scarce – effective demand seems to be largely sated.

And what of the argument that “we’ve done the Unitary Plan and prices aren’t coming down, so the problem can’t be land regulation”? Well, yes, of course it can. If anything, given the manifestly obscene prices people face for land in or around Auckland, Auckland Council officials (and their political masters) should be looking at the failure of land prices to fall back and concluding that their latest planners’ vision had failed. It is all very well to talk of the potential for a million more houses, but these are the sorts of lines local authorities have run for a long time – I recall councils running these lines when the 2025 Taskforce was looking at these issues. I haven’t looked into the “million house claim” in any depth, but as I understand it, much of this potential is about the possibility of increased density on properties that the existing owners are simply never going to sell (they like living in their existing house/location). There was probably a lot of theoretical capacity before the Unitary Plan, and of course there has been a lot more population pressure in recent years.

And the bigger issue is that when Council planners and politicians deem that certain places can be built on and others can’t etc etc, there isn’t much of the market at work. A well-functioning land market would be one in which developers and land owners on the fringes of growing cities were in active competition with each other as to which could supply new sections and new homes more effectively, and where those options in turn competed with realistic options for increased density (according to the tastes/incomes of potential purchasers, not the whims and preferences of officials and politicians). In a competitive market, holding costs are quite substantial – not so where regulation rewards “land-banking” – rewarding bringing land to market early.

The Auckland Council economists’ final line is cute in a way

In the case of Auckland at least, the answer is simple: You can’t live in a resource consent. It is because not enough houses are being built fast enough (for a range of reasons), rather than just the technical availability of developable land, that is keeping prices up. Land may be resource consented for development, but until houses are actually built on it, a premium will be placed on houses that are available.

And, of course, one can’t live in a consent, and we know from other work that the net addition to the housing stock in Auckland has been well less than the number of consents issued for various reasons (including that densification often loses existing houses). But the point isn’t really relevant to the claim the economists are trying to rebut.

I did a brief post last year on one small example of undeveloped land on the fringes of Auckland – property at Dairy Flat, still some years from actual development – where various plots were selling at an average of $1.266 million per hectare. When that sort of land – with no prospect of a house on it for the next few years – is still that expensive – land which for rural purposes might be worth $30000 per hectare – we know there is still something very wrong with land use regulation as it is being applied in Auckland. If one looked, I can only assume we’d find similar examples around Tauranga.

None of this is deny that there might be problems around consenting processes, construction costs (and the construction products supply chain), and/or infrastructure, but please Auckland City stop trying to pretend that black is white and that land use regulation is not a major part of why house price to income ratios are so high in New Zealand – not just in Auckland, or even Tauranga, but in places with few natural obstacles and modest population growth like Napier-Hastings, Christchurch, or even Palmerston North.