Today’s labour market data seem to point again to the underperformance of the New Zealand economy. Oh, the headline rates of GDP growth haven’t looked too bad – although they are quite modest in comparison with previous New Zealand growth cycles – and employment growth has been strong. But to what end? Labour productivity looks still to be shockingly weak, yet another year ends with the unemployment rate well above Treasury estimates of NAIRU, and even as core inflation has picked up somewhat (yesterday’s post) wage inflation seems to be about as subdued as ever. There seems to be something quite wrong with the economic strategy that presides over such outcomes – and no sign from the major opposition parties that they have anything materially better or different to offer.

Hours worked, as captured in the HLFS, have increased strongly in the last five quarters, up by 6 per cent (adjusting for the break in the series, because of new methodology in the June quarter last year). There have only been a couple of periods in the 30 year history of the series that have seen growth in hours worked that rapid.

We don’t have GDP data for the December quarter yet, and of course earlier quarters are always subject to revision. But for the four quarters we do have, real GDP (averaging expenditure and production measures) rose by 4.0 per cent. In other words, unless quarterly GDP growth for the December quarter is at least 1.9 per cent, we’ll again have had no productivity growth at all during that five quarters of rapid growth in hours worked. Few commentators I’ve seen think GDP growth was anything like that strong – something a bit over 1 per cent seems closer to expectations. If so, we’ll have had really rapid increases in hours worked and employment, but the economy will have got less productive at the same time. (And recall that we’ve now had five years of no productivity growth).

In the past, periods when growth in hours worked have been very strong haven’t always seen rapid productivity growth. There can be good reasons for that, if (on average) lower productivity workers are being reabsorbed into employment for example. In the early-mid 1990s we had a couple of years of very rapid growth in hours worked, and over that period productivity growth, although positive, was pretty weak. But over that couple of years the unemployment rate fell from around 10 per cent to around 6 per cent, and the employment rate also rose by around 4 percentage points.

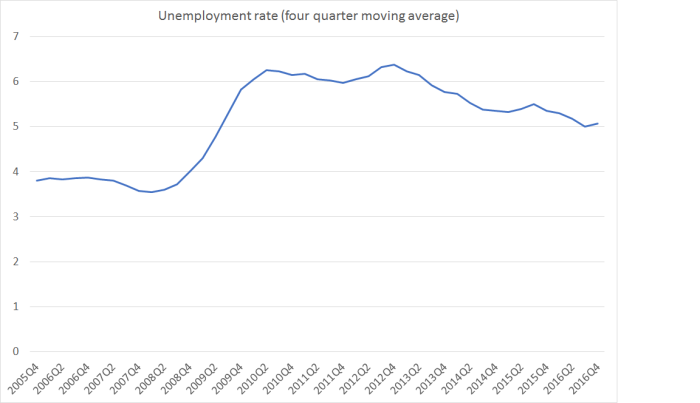

Here is the unemployment rate (four quarter moving average to smooth through some of the quarterly noise, down and up)

The unemployment is still slowly trending downwards, but the pace is quite excruciatingly slow. Over the five years in which there has been no productivity growth, the average unemployment rate has fallen from around 6 per cent to around 5 per cent, and over that period Treasury estimates that the natural rate of unemployment (determined by things like demographics, welfare provisions and labour market regulation) has been falling – and is now around 4 per cent.

The unemployment is still slowly trending downwards, but the pace is quite excruciatingly slow. Over the five years in which there has been no productivity growth, the average unemployment rate has fallen from around 6 per cent to around 5 per cent, and over that period Treasury estimates that the natural rate of unemployment (determined by things like demographics, welfare provisions and labour market regulation) has been falling – and is now around 4 per cent.

So we’ve had:

- no productivity growth (perhaps even a contraction over the last year)

- high and only slowly falling unemployment (and for those inclined to glibly respond that 5 per cent unemployment isn’t high, recall that that numbers mean that any one time one in 20 of those people available for wanting, wanting to work and making active efforts to find work can’t find a job).

And what of wage increases? Unsurprisingly perhaps, there has been little sign of any recovery nominal wage inflation. A standard response is that wages will inevitably lag improvements in the labour market, but….the unemployment rate has now been falling slowly for five years or so.

There is a variety of different wage inflation measures. Here are two from the Labour Cost Index – both the headline published series, which tries to adjust for productivity growth, and the Analytical Unadjusted index which is more like a raw measure of wage inflation. In both cases, I’ve shown the data for the private sector.

Of course, if one believes this data (in particular the red line) there must have been some continuing productivity growth in New Zealand, even if at a slower rate than previously. Quite why SNZ finds (implied) productivity growth here, and not in national accounts (real GDP per hour worked) is a bit of a mystery.

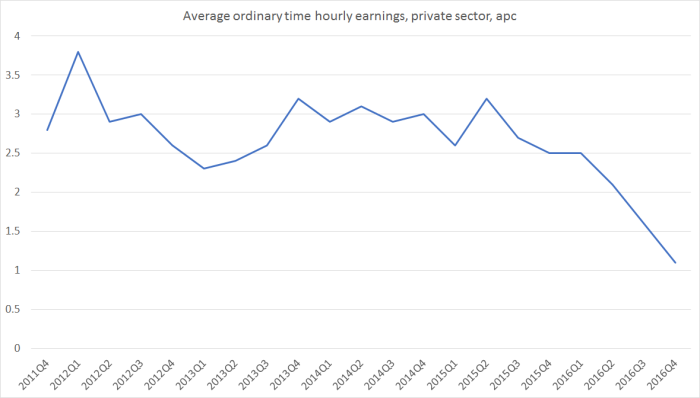

The other measure of wage increases if from the QES. In this case, the annual rate of increase in private sector ordinary time hourly wages.

There is some volatility in this series, and I’m not sure I’d want to put much at all on the reported sharp fall-off in hourly wage inflation over the last year, but…….there is certainly no sign of an increase in wage inflation.

It is always easy to look around and find countries that have done worse than New Zealand – several of the euro area countries spring readily to mind. But our performance, and the gains for our people, are nothing much to celebrate. And while, for example, there has been a global slowdown in productivity growth since the mid 2000s, New Zealand’s productivity levels are so far below those of the more strongly performing OECD countries, that there was no necessary reason why we needed to share in the slowdown. It should, if anything, have been an opportunity for some convergence. But there has been no sign at all of that.

I don’t find that particularly surprising – an economic strategy that appears to involve attracting ever more people to one of the most isolated corners on earth, in an era in which connections, contacts, and proximity seem to matter more than ever, all while producing a very high real exchange rate (again resurgent in recent weeks/months), and the highest real interest rates in the advanced world, is simply a recipe for continued long-term underperformance. One would like to think that the government – and the Opposition which seems to support very similar policies – has been surprised. They can’t, surely, have planned on such a bad performance. But persistent bad outcomes, of the sort New Zealand continues to see, should be prompting some serious policy rethinks, not just more PR about how rapidly employment numbers are growing.