The Reserve Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee yesterday delivered their latest OCR review.

In my post on Tuesday, in which I suggested that an OCR cut was appropriate now, I’d noted

As it happens, yesterday was another reminder that it is unwise ever to bet against Reserve Bank induced volatility, sometimes intended, sometimes not.

You’ll recall that the May MPS (forecasts and words) was a lurch in the hawkish direction. This was their OCR track, revised out and up, showing an on-balance probability of OCR increases for the rest of this year, and nothing below the current rate until the August 2025 Monetary Policy Statement.

and this was a chart I’d constructed from the same projections:

Real interest rates kept on rising until the second half of next year, but somehow – as if by magic (given the absence of domestic or external macro stimulus) – the economy gradually recovered anyway.

The MPC then seemed to have barely understood what it was doing, and a couple of days later the chief economist was indulging in the old bad workman’s excuse (blaming his tools). We weren’t really meaning to suggest possible rate hikes, they claimed. but if so why publish the projections that showed exactly that, when any half-competent MPC member would have known precisely how they’d have been read? And in the end the markets seemed all rather underwhelmed and unconvinced and didn’t really move much at all.

But say what you like about the May MPS, at least it was done in the context of a full set of economic and inflation forecasts. And it was finalised with the full MPC present.

By contrast, what of yesterday’s statement? Not only wasn’t there a full set of forecasts (internally, let alone published), but the Bank’s chief economist – who is presumably primarily responsible for both sets of forecasts and economic analysis – had been allowed to go off on leave and wasn’t even at the meeting (they only happen seven times a year). And there really hasn’t been that much data since late May, and none of it that (to my eye anyway) seemed particularly surprising or game-changing. Most notably, especially in the context of all the explicit concerns in the May MPS, there hasn’t even been another CPI outcome (and the Bank rashly chooses to do these reviews a week before the CPI comes out).

Now, as it happens I think the view articulated in yesterday’s statement is much better and much more likely to accurately reflect what is going on, and is likely to go on, in the economy and inflation than the one delivered in May. And in that sense, and in isolation, I welcome it. Perhaps the two new MPC members have begun to make some useful difference (although in the culture, and under the obligations of silence they’ve assumed, we may never know – we get much more openness from our Supreme Court justices than we do from MPC members).

But we should be able to expect better than such policy lurches, that are neither signalled in advance (none of the frequent speeches we see in the better and more open central banks) nor evidently grounded in big shifts in hard data. Take as just one example: the May MPS was full of worries about and references to non-tradables inflation. The chief economist’s speech just a few weeks ago was in the same vein, and if anything more stark. By contrast, in yesterday’s two page statement there was not a mention, and barely even an allusion. And did I mention that in meantime we haven’t had a CPI outcome (in fact since April)?

It really isn’t good enough. In fact, it is amateur hour stuff from a statutory committee, allegedly with some expertise, which has been delegated by Parliament a huge amount of power and influence and yet seems to face almost no real accountability (apart perhaps from an ever-growing lack of respect, as if that seems to matter to Orr et al).

This time it seems that they did move the market (significant changes in both the exchange rate and short-term interest rates). And you can see why that might be the case. This was the concluding line in May

and this was yesterday’s

One is a great deal looser, leaning towards easing, than the other. That is especially so when they chose to frame yesterday’s statement in terms not of inflation itself, but of “inflation pressure” (usually a reference to the economic imbalances – output gaps, unemployment etc – that precede changes in inflation).

Combined with a unqualified statement that they are confident inflation will be under 3 per cent this year, and rather gloomy comments on the state of activity and demand, it would normally be a pretty strong signal of the likelihood of an OCR cut really rather soon (perhaps even in August).

But this is the MPC we are dealing with. Having lurched in one direction in May, in the other direction (without much data or a full set of forecasts) in early July, who knows where they will be by late August? No doubt next week’s CPI should be quite important, perhaps even decisive now in a normal MPC, but…..this is the Orr/Quigley MPC.

It really isn’t good enough. A couple of weeks ago the Associate Minister of Finance was defending the weird reappointment of Neil Quigley (as if everything had just been fine in the Bank), with a claim that too much “chopping and changing” wasn’t a good thing.

Quigley has been chair, through all the various mishaps, for eight years already. The MPC that he is responsible for – the Board determines who ministers can appoint or reappoint – can’t hold a stable view for even six weeks at a time.

But there is no sign any of it bothers the Minister of Finance, primarily responsible for the Bank and for Quigley/Orr, or presumably her boss or the rest of the Cabinet.

And perhaps again it is time to reflect on the monolithic approach to the MPC put in place by Orr/Quigley, with the imprimatur first of Grant Robertson and now apparently (since she has done nothing to change it) endorsed by Nicola Willis.

Monetary policy is an area of legitimate and real uncertainty. As I noted in the post earlier in the week, if ever a policymaker isn’t conscious of much uncertainty, either they aren’t thinking hard enough or they’ve left things far too late. But go back and read the May MPS, and you will search in vain for any sign of intelligent differences of opinion. There simply is none. In fact this is the only use of “some members” in the entire document

Nothing at all of different models of how things are playing out here, or how monetary policy might best respond. These are matters of real uncertainty (at least among sentient thinking people).

And as demonstrated by the fact that only six weeks later the Committee had lurched to a materially different position. And again unanimously. This time the only “some members” was this statement of the blindingly obvious.

This is a Committee that simply has not earned anything like deference. It, like any powerful goverment entity but perhaps especially after the record of recent years, deserves constant scrutiny and real accountability. Instead, we get lurches and bluster….and a government so unbothered they reappoint the man directly responsible for the MPC (appointments and performance) to yet another term.

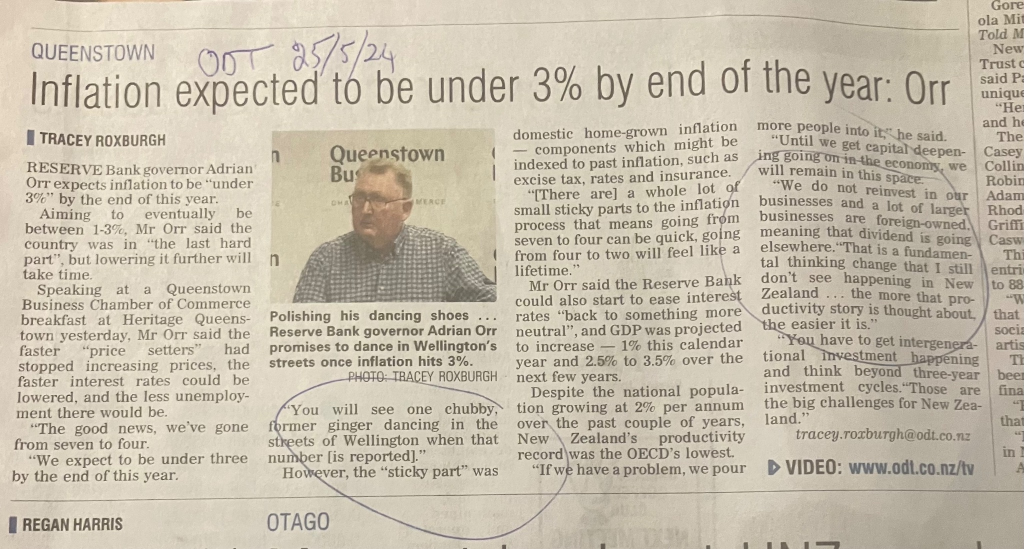

On a slightly lighter note to end, the Committee yesterday expressed unconditional confidence that inflation will be under 3 per cent this year. You may recall this, little-reported, line from the Governor, captured by an ODT reporter just after the last MPS

From my comments at the time

We should be getting, and really need, something much better, much more commanding of respect and confidence, from our central bank. That is on the Minister of Finance. But she shows no sign of caring.