This morning as the Quigley/Orr/Board saga rumbles on I wanted to touch on three items:

- the latest comments from Board chair Neil Quigley (and the Minister’s comments on and to him)

- a reminder of where this all started, with the Board unanimously approving a budget last year far in excess of what had been approved under their then-current Funding Agreement, and

- outstanding OIAs.

Quigley

When I wrote my post yesterday morning I’d seen only Quigley’s extraordinary jaw-dropping comments to interest.co.nz suggesting that he had been deliberately (to say the least) economical with the truth and actively misleading the public because they had no right, or particular need, to know. And when Brunskill suggested that this was perhaps inconsistent with the Bank’s oft-boasted commitment to transparency, Quigley let loose with the classic line that “I’m not interested in having you question me like you’re a lawyer”. A journalist doing his job would have been more like it…. It was, sadly, consistent with the Quigley who has long acted as if public affairs are matters only for the chosen and that the great unwashed should really pipe down and be grateful.

Then I saw another story from Brunskill in which he recorded that in a follow-up email Quigley had said that an agreement with Orr limited “the communication we could offer on March 5”. Which may well have been true, but doesn’t take us any further since

(a) it was Orr who resigned, and there were presumably standard resignation terms in his contract,

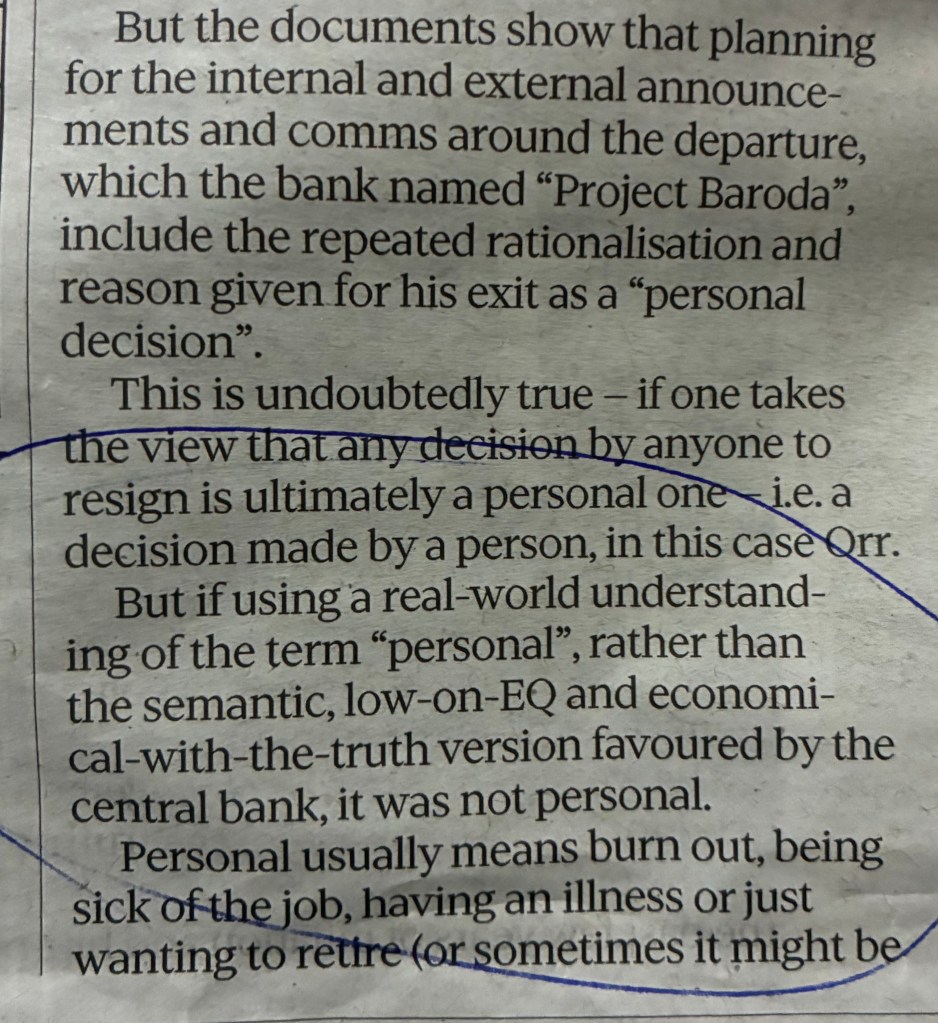

b) even if they had mutually agreed that the only comment on 5 March would be the agreed official press release i) Quigley did not need to agree to content that actively misled the public (reread the statement it is clearly designed to give the impression of “nothing to see here”, but perhaps suggestive of a long-serving CE who was tired and had accomplished what needed doing), and ii) it was Quigley who chose to give the press conference later that afternoon in which he clearly went well beyond the press release, trying fairly explicit to suggest that it was all just personal reasons – but not conduct or anything of the sort – and more or less explicitly denied it had anything to do with (the emotional overreaction to disappointment around) the forthcoming Funding Agreement.

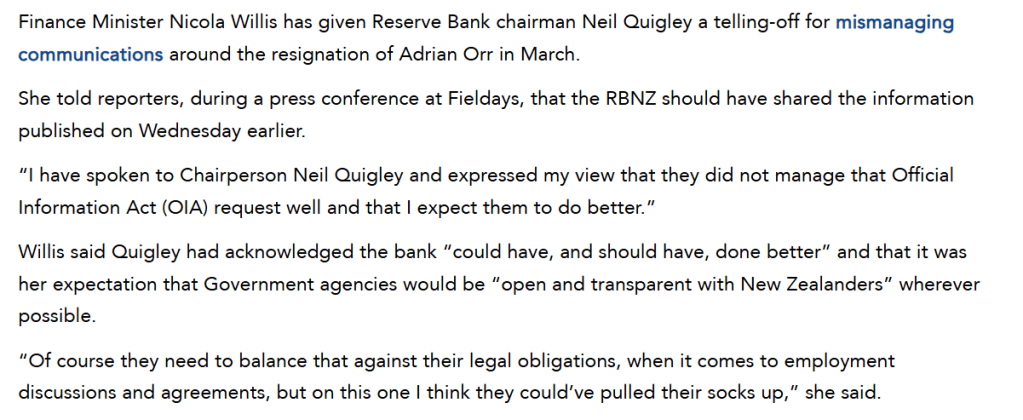

Then the Minister of Finance entered the picture, giving a press conference at Fieldays (account here)

Which was a good start, although re that final paragraph note that the Board (Quigley) chose what to agree to in the exit agreement. It seems to have been Orr who wanted out. Quigley should have been acting to protect the interests of New Zealanders, including in transparency and accountability.

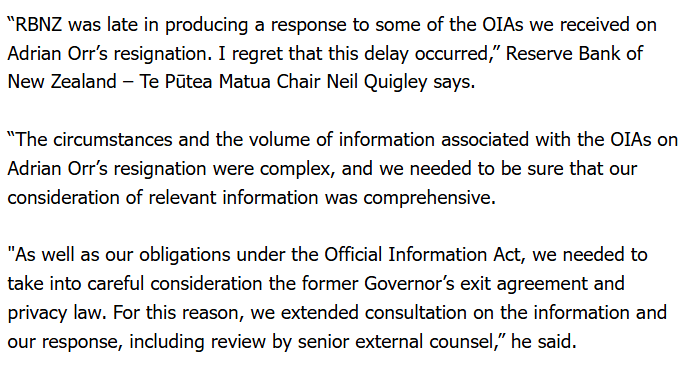

And then a few hours later a statement emerged from Quigley himself. It came via the Bank’s standard email advisory list (link here to a website version). I really don’t think it helped (and from people I’ve talked to I’m not the only one).

He started with this

“Late” doesn’t even begin to describe it. The bundle they have released – while interesting and revealing in itself – hides as much as it reveals, including almost everything about Quigley’s role, and does not even touch on large chunks of my request (not sure about others but my impression from reading coverage is that others are similarly underwhelmed). And the law is the law, and they knew from day 1 (well actually from when Adrian first said he was going) that there would be intense public interest in this and should have been pro-actively positioned to provide a comprehensive response early, for public and for staff.

As for that 3rd para, as noted above while Orr’s employment contract was a given, it was Quigley who decided what sort of non-disclosure restrictions to accept/impose.

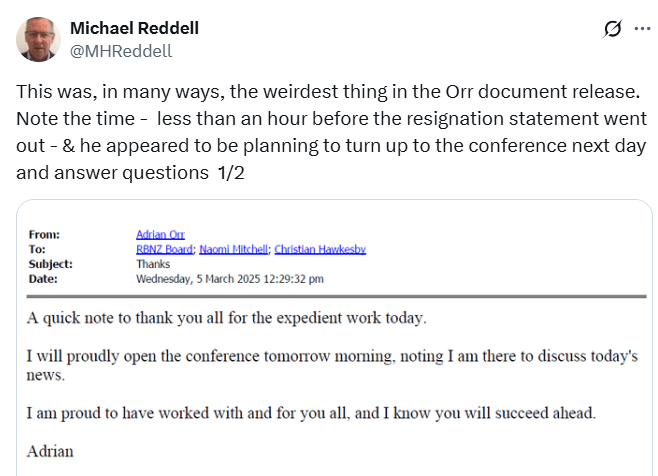

Note that in the early afternoon of 5 March, just an hour before the resignation statement went out, Orr was planning to front the conference the next day and “discuss today’s news”.

As it happened, going through some old articles this morning I found one from 5 March when Dan Brunskill had door-stopped Quigley and asked him about the conference (“Quigley said he did not know whether Orr would still host the central bank’s monetary policy conference”) He had sorted that out by the time of his ill-starred press conference later in the afternoon, but none of it feels like some advance commitment that Orr would disappear in utter silence and no answers would be given for months.

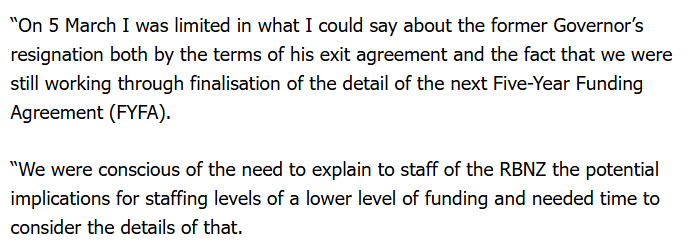

The second bit of Quigley’s statement was this

On the first para:

- even if there had been an agreement that the only public comment on 5 March would be the official agreed press release (a not unreasonable approach in itself), a) Quigley had a great degree of control over what was (and wasn’t) said in any statement, and b) why then did he seem to go off-reservation with a press conference where again and again he seems to have actively misled the public (acknowledging to Brunskill on Wednesday that he had done so deliberately?

- the fact that the Funding Agreement hadn’t been finalised is really just distraction. The Minister had already said in public the previous week that she was looking for cuts, documents released show even Orr was reconciled to a lower level of spending than they’d initially asked for (even if not to what the Board was willing to go to to reach agreement with MoF). What stopped them saying “negotiations between the Board and Minister on the next funding agreement are progressing. In straitened fiscal times it is unsurprising that the Minister is looking for cuts. The Governor did not believe that the scale of cuts sought was appropriate and chose to resign”. Sure, it would have been uncomfortable, but….that is what real accountability and transparency means. (And anyway, the Funding Agreement was published in mid April and we got no disclosure until 11 June.)

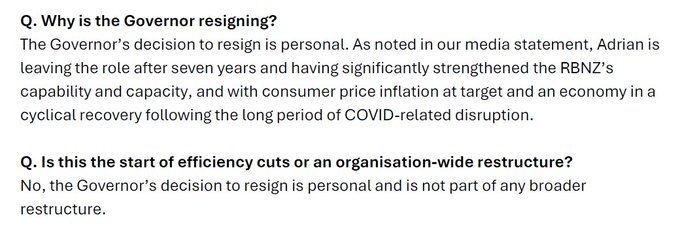

As for the second para, their treatment of their staff seems to have been particularly egregious. Recall this from their internal Q&As for managers to use with staff.

They lied. They – Board and remaining senior management – had known for weeks at least (it is the released documents) that staff cuts were going to be necessary. That is more or less what public sector budget cuts meant across the board. Staff are adults. They know that. Sure, the final budget numbers hadn’t been determined but it would have been perfectly possible – they had days to do it – to have crafted a message for staff that said “it is now certain that our funding next year will be materially lower than this year’s operating budget. We do not know how much lower but the implications will certainly include staff cuts this year”.

Or, slightly less bad perhaps than the way they actually treated staff, they could just have stonewalled and said “no comment, no comment, no comment” when staff asked what was going on.

Can Quigley survive? He certainly shouldn’t but who knows. When a journalist asked me last night I noted that since I didn’t adequately understand why Willis had reappointed Quigley for a final two year term last year, one couldn’t be confident she’d do the right and necessary thing, but I still reckoned that within a month there was a better than ever chance he’d be gone. Victoria University’s Martien Lubberink suggested on Twitter last night that he was buying a lettuce. The original lettuce outlasted Liz Truss. I hope this one lasts longer than Quigley. Any good he did in his 15 years on the board seems long long past and there needs to be change at the top now.

Budgets

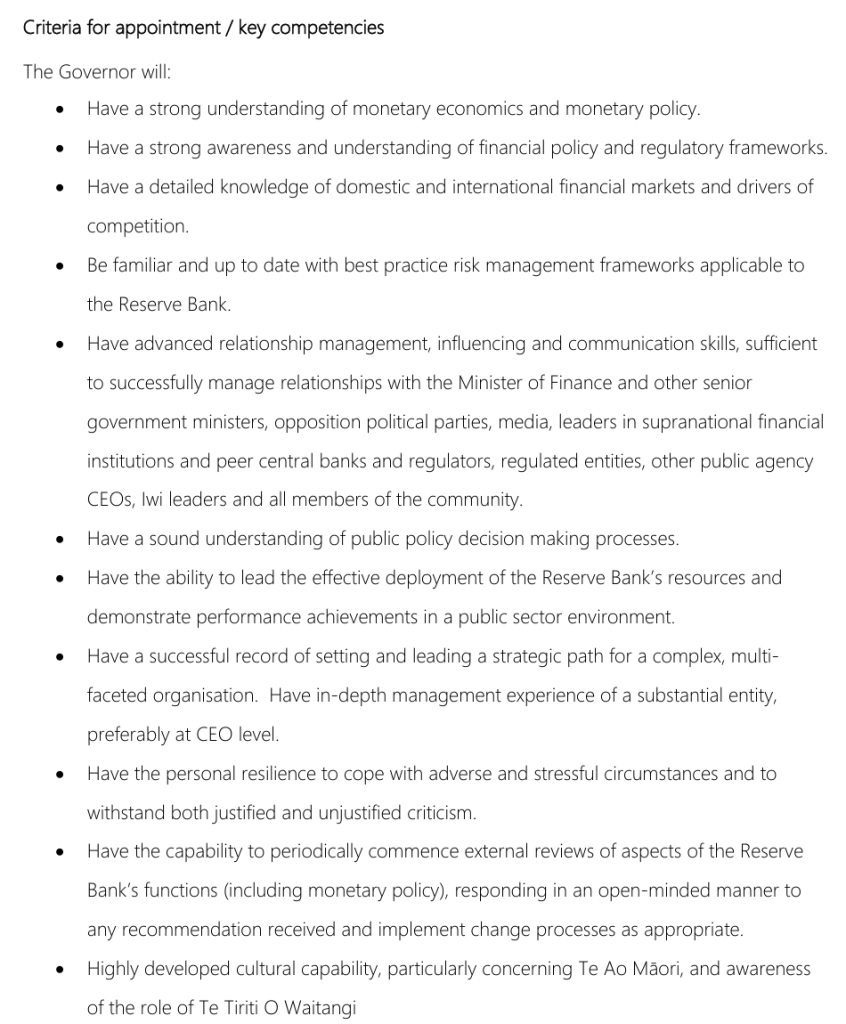

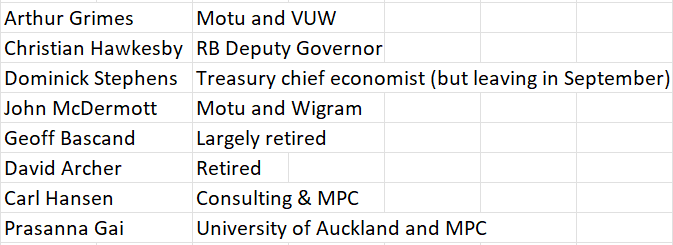

I was in a meeting yesterday and chatting over lunch with people who aren’t very focused on central banking or government finance issues, and a couple asked “what was Orr planning to do with all that money?” My response was simple: it wasn’t what he was planning to do in the future, but rather that the money had already been spent. And in breach of the Funding Agreement they’d signed with the Minister of Finance in mid 2023 (an agreement that covered the 23/24 and 24/25 financial years, amending the 2020-25 five-yearly Funding Agreement).

All the details of this are in a post I wrote last month. But to quickly summarise:

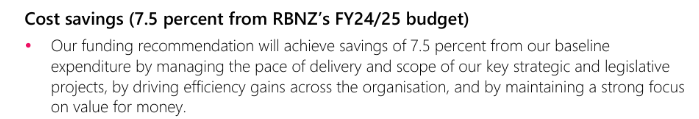

- in that 2023 amendment the Bank had been allowed to spend about $154.4 million on (within scope) operating expenses in 2024/25,

- the Bank’s Board adopted on operating budget for the same (within scope) items for 24/25 of $191 million, 23 per cent above the level of operating expenses Grant Robertson had allowed them for 24/25. This Budget was adopted unanimously by the Bank’s Board last June (and overall budget numbers were included in the Statement of Performance Expectations published then),

- the Bank’s bid in respect of its next Funding Agreement, also adopted unanimously by the Board, involved a 7.5 per cent cut from that $191 million level (with a bit of sleight of hand in proposing to move some more things out of scope).

If you doubt the story, here it is in their own words

Spend up hugely, far beyond what the Minister of Finance had allowed – something no other government agency or department could do – and then offer up modest savings relatively to that grossly inflated (and improperly authorised level).

Consistent with this, they’d increased staff numbers from, 601 to 660 between 30 June last year and 31 January, and the documents revealed Orr talking of a plan to take it as far as 742.

It really was that simple, that extraordinary. And if it represents an abuse of office in respect of New Zealand taxpayers, it was almost worse in respect of their own staff. People had taken on new jobs in those last few months as the empire continued to be built even as Board and management were (at best) deceiving themselves about the fiscal environment and the sort of restraint that might reasonably be expected from them (as most other public agencies).

Now, there are still a couple of puzzles around the role of the Minister and Treasury. As my detailed post documents, the Minister of Finance had to be consulted on that Statement of Performance Expectations (containing the budget). We do not yet know whether she ever pushed back strongly at that stage (just after last year’s government budget).

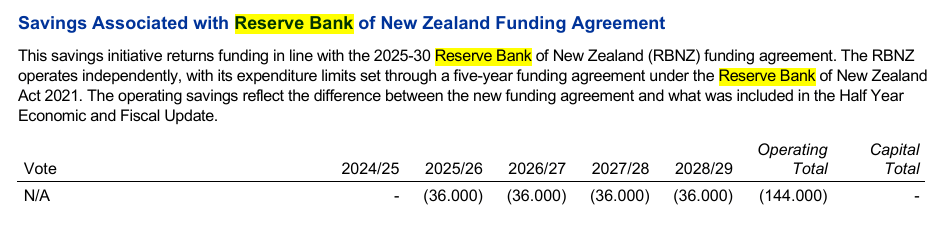

And then there was this, spotted in the recent (government) Budget Summary of Initiatives document

The savings are good, but it looks as though Treasury had included in the HYEFU numbers much much higher levels of spending than the Minister eventually accepted, and more in line with the Bank’s opening bid. Why did they do that, when those higher levels were well above the previous Funding Agreement? Had conversations with the Minister in the second half of last year indicated that she was then fairly relaxed? We do not know (but really should).

So, it was never a bid for even more, it was about consolidating most of the extraordinary growth in spending and staff in recent years, the last and most egregious bit (in 24/25) having happened without any ministerial authorisation, quite inconsistent with the statutory instrument governing Bank spending, the 2025-30 (amended) Funding Agreement.

Outstanding OIAs

I saw a serious observer on Twitter the other day note that he’d had several OIAs in with the RB since February (clearly not Orr resignation related) and had not yet had a response.

My experience isn’t that bad, but…..

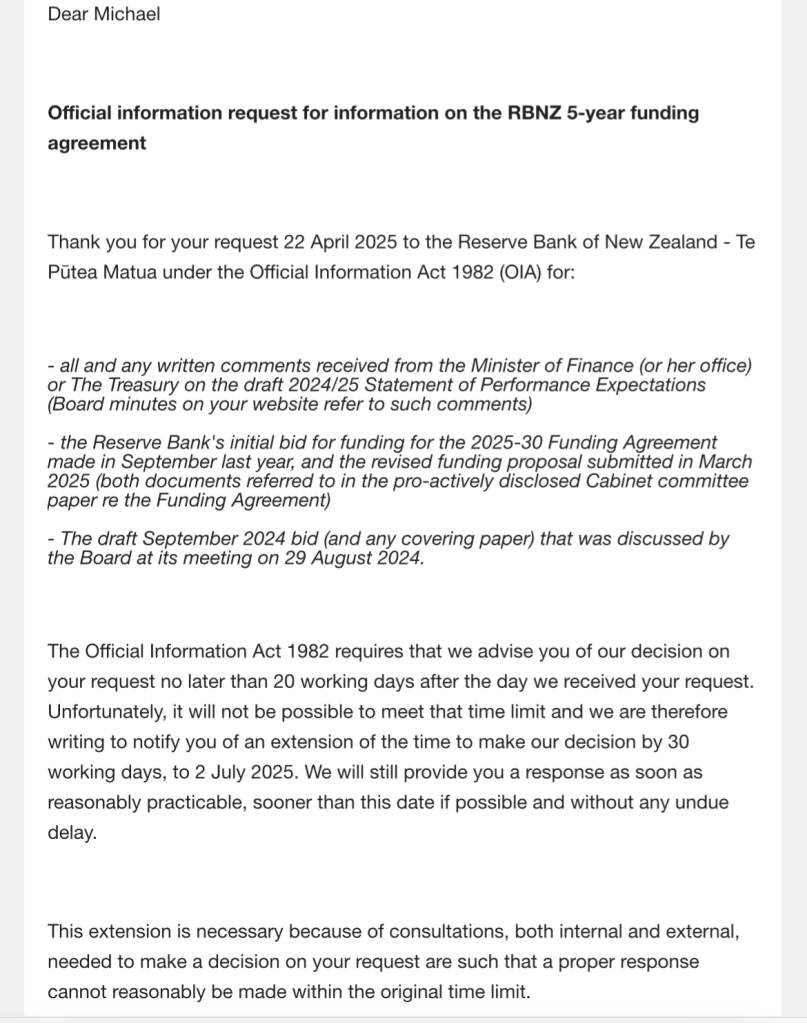

On the spending levels and the Minister’s involvement, I still have this outstanding

All this will have been readily accessible. If Quigley is serious about sharpening up the Bank’s OIA act, perhaps he could get them to address this one rather more promptly.

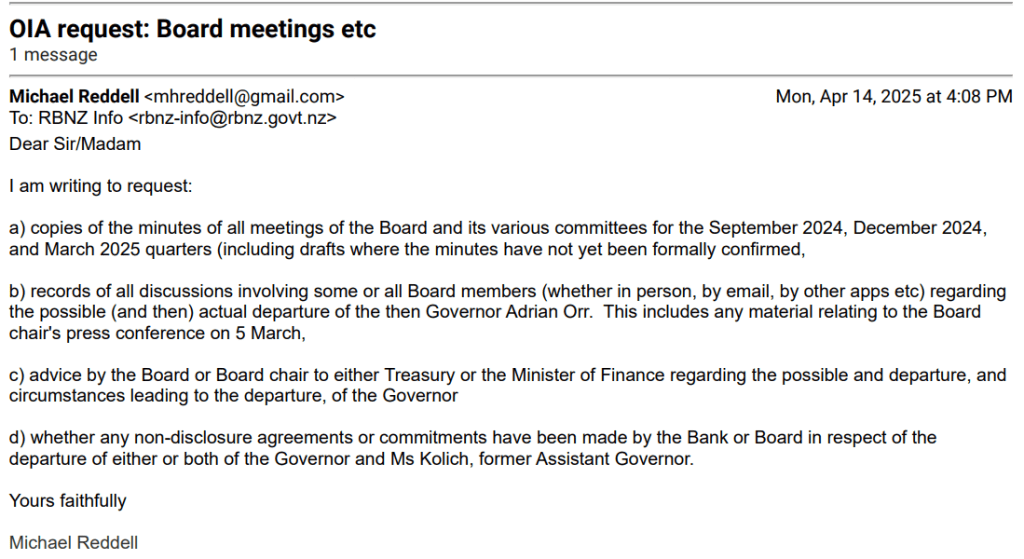

And then there was my request regarding the Orr resignation events. I didn’t put one in until quite late, and deliberately touched on only some specific aspects. This was lodged with them on 14 April

In their official response to me on Wednesday they claimed that the document dump dealt with this request.

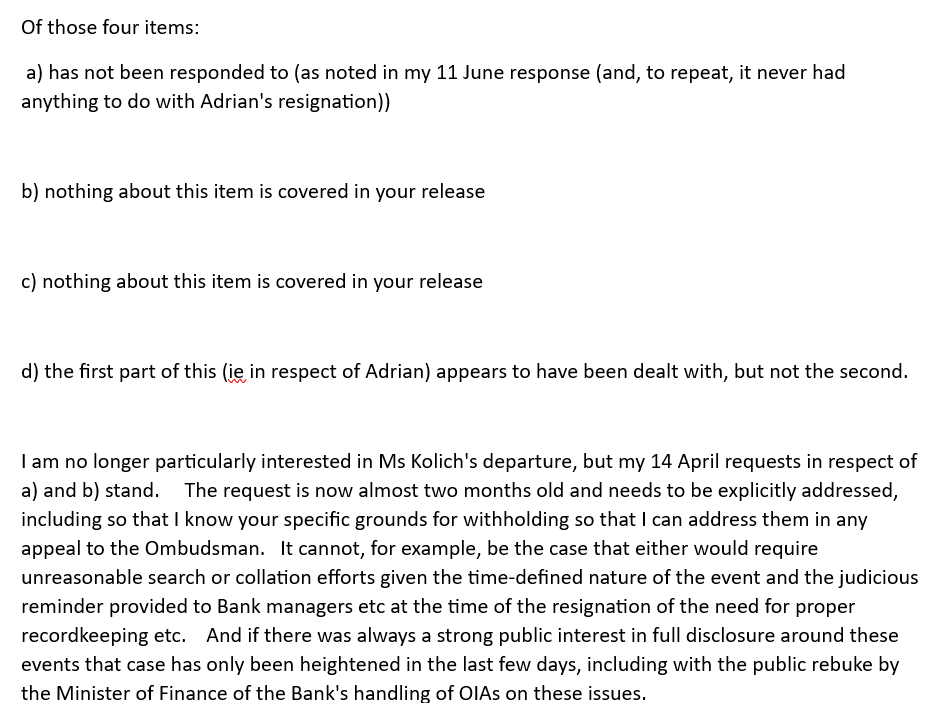

It didn’t. I had already pointed out to them that the first request had almost nothing to do with the Governor’s resignation (and of course nothing in the release dealt with that). This morning I went back to them as follows

It is as if they either can’t/won’t read, or somehow think the Official Information Act doesn’t apply to them. I’m not optimistic of getting anything more (well, at best this side of 2028 if it involves the Ombudsman), but they can’t get away with claiming they’ve responded to OIAs they’ve chosen to ignore.

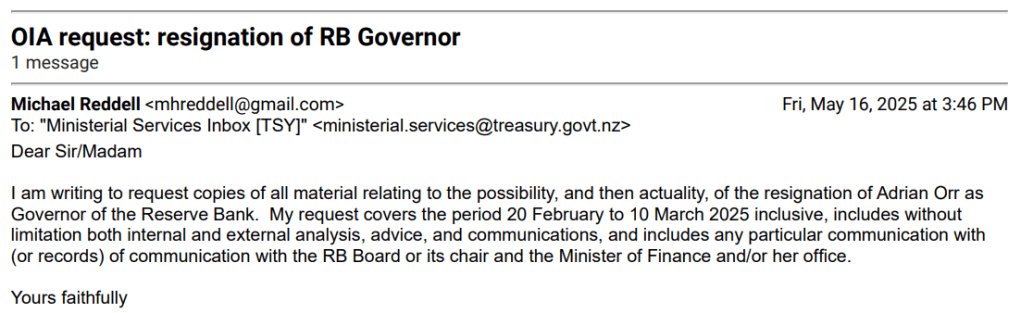

And then there is this outstanding from The Treasury, which should be due in the next few days.