In the few weeks since the Financial Times/Newsroom story about Jian Yang broke and, independently, Professor Anne-Marie Brady’s conference paper on the extent of People’s Republic of China influence-seeking activities in New Zealand became available I’ve been doing a bit of reading around the issues. As far as I can tell, overseas experts appear to see Professor Brady’s paper as portraying a situation in New Zealand that is more extreme than (and more successful?), but consistent with the direction of, PRC activities in a range of other countries. Her paper seems to have attracted quite a lot of interest abroad, even as our own politicians (in particular) and media have largely overlooked the apparently serious issues she raises. The approach of successive governments, but perhaps particularly the most recent one, appears to closely resemble “never, ever, say anything to offend Beijing”.

In the course of reading around the issue, I found a couple of interesting papers on the MFAT website. The first, Opening doors to China: New Zealand’s 2015 Vision, was released in 2012. It is currently described as

The NZ Inc China Strategy maps the possibilities for the relationship on a 10-15 year horizon.

The document is totally consistent with the relentlessly upbeat and deferential tone that seems to characterise the New Zealand government’s approach to China. It begins with a Foreword from the then Prime Minister John Key.

With its talk of “centralised plans” it seems strangely apt for China.

The NZ Inc China Strategy is the second in the Government’s series of centralised plans – developed to strengthen our economic, political and security relationships with countries and regions, and to encourage people-to-people links and two-way investment.

He continues, in a paragraph that rather gives the game away.

Our strategy for China starts from an explicit recognition that an excellent political relationship is the foundation upon which everything else must be built. We can’t engage with China just on the trading front – we need to work across all sectors to build the range of links that will enhance our understanding and familiarity with one another.

That isn’t how normal countries, and firms in them, typically operate. Trade is, largely, a firm to firm matter, and governments set overarching standards and (largely) stand back. But not with China: that compliant political relationship really seems to matter.

Even the economics seem shonky, or (deliberately?) naïve.

Knowledge is in fact set to be a key driver of our rapidly growing relationship. Clearly it is a two-way street – we want to work with China to drive forward science and technology linkages, and we want to exploit the fruits of that collaboration to the commercial advantage of both countries.

But China isn’t at the leading-edge of technological innovation – thus, it is still a relatively poor middle income country – and while it has had a strong interest in acquiring western technology, by legal means or otherwise (so much so that research agreements between western universities and Chinese interests are raising increasing concerns), there is considerably less evidence of a “two-way street”.

Key concludes

The New Zealand Inc China strategy articulates the vision of a relationship with China that stimulates New Zealand’s innovation, learning and economic growth.

I won’t blame the New Zealand-China relationship for the lack of any productivity growth at all in New Zealand for the last five years. But perhaps we could just say that the claimed benefits to the wider New Zealand economy are still somewhat hard to identify.

I’m not going to comment on the detail of the rest of the 40-page document, which is full is pretty upbeat stories, and some (no doubt) useful advice to firms considering China. But this snippet did grab my attention, as I suspect it captures the flawed mindset that lies behind so much of our government’s approach to China.

China’s increasing economic success has given it greater influence in regional and international politics. Its prosperity has driven prosperity and stability throughout the Asia-Pacific region.

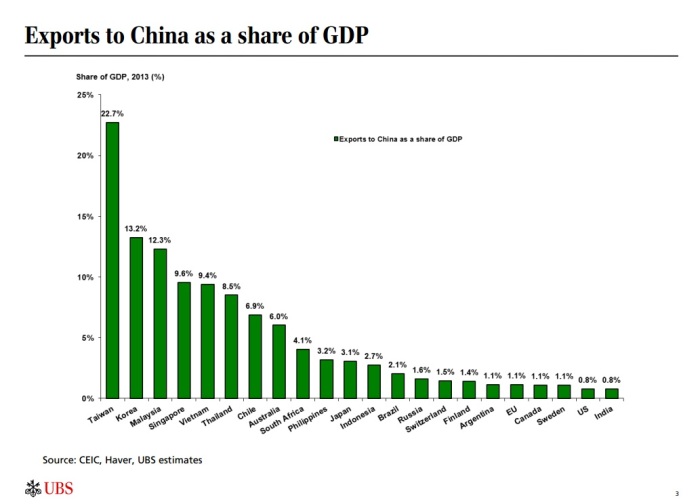

But that simply isn’t true on either count. Singapore, Taiwan, South Korea and Japan – the advanced countries of east Asia – aren’t rich because of the People’s Republic of China, but because they had their own policies, institutions, and people that equipped them to catch up with the leading economies of the West (something China is still failing to do). As for “stability” well it isn’t my field, but I doubt it is an impression shared by China’s neighbours dealing with its South China Sea expansionism. (I’ll try to do a separate post on the fallaciousness of the proposition that New Zealand’s economic prosperity, wellbeing, or stability depends to any large extent on China, hopefully drawing from some possible historical parallels.)

As is perhaps so often the case, what is missing from the document – the shop-front of the government’s China strategy, whether for firms looking to operate in China, or for citizens interested in evaluating government policy – is as interesting as what is there. There is no mention of how deeply corrupt much of China is, there is no mention of the pervasive controlling role of the Chinese Communist Party (generally regarded as more important than the state itself), and nothing on the absence of the rule of law (which means not the presence of courts, but the willingness to have independent judges apply laws impartially even when it doesn’t suit the authorities). You have to wonder whose interests those omissions serve. Beijing is no doubt happy. Established businesses trying to protect their interests in China may be too. Big China-associated donors to major parties might be. But this is supposed to be a government of 4.8 million New Zealanders.

The other document I found on the MFAT website suggested that, in fact, at least among some officials there is a rather greater degree of realism about China than politicians seem ever willing to allow. In conjunction with MFAT, the Victoria University Contemporary China Research Centre is conducting five-day “master classes” for public servants. The purpose is described as

To develop a pipeline of China-savvy public sector professionals with global perspective and deep insight into the political, economic, security and cultural dimensions of the New Zealand government’s relationship with China.

It looks like a really interesting course. Among the speakers they have the retired ANU China expert, Geremie Barme, now resident in the Wairarapa, whose post on Professor Brady’s paper I linked to the other day.

Among the themes course participants will be considering are:

• The three Chinas: through the eyes of the Party, its history, and a leading global Sinophile

• What it means to be China savvy – developing a political, economic, security and perspective

• The peculiarities of media in China and the roles that Party and government play in controlling media

• The role the Chinese government takes in the threat of commercial failure to safety of Chinese. people in China and for Chinese outside of China.

• The nuances of building and protecting a brand in China, the Chinese legal system and the cultural nuances when doing business in China

• The profile of the modern Chinese in New Zealand and media influence on Chinese youth abroad.

But if this shows signs of a greater degree of realism, there are clearly limits. In the brochure for next month’s course it states of Day 1.

Scenarios throughout the day cover visiting delegations, the Māori-Chinese relationship, and navigating authorities.

But I also happened to find on-line a brochure for a version of the course run earlier this year. In that brochure it says of day 1.

Scenarios throughout the day cover visiting delegations, being Chinese in New Zealand, corruption issues, and the party-state structure.

Perhaps that was getting just a bit too close for comfort?

Last night I finished re-reading Richard McGregor’s excellent 2010 book The Party. On his final page, there were a couple of telling quotes.

The Chinese communist system is, in many way, rotten, costly, corrupt and often dysfunctional.

And

China has long known something that many in developed countries are only now beginning to grasp, that the Chinese Communist Party and its leaders have never wanted to be the West when they grow up. For the foreseeable future, it looks as though their wish, to bestride the world as a colossus on their own implacable terms, will come true.

That was, of course, written before the ascendancy of Xi Jinping.

Somewhat more immediately, a couple of people last night sent me a link to a new article by Charles Finny, former senior diplomat, and now a partner in the government relations firm Saunders Unsworth (where he describes himself as “making the impossible possible”). For someone who knows a great deal about China, and must surely be well aware of the sort of regime it is, and the nature of its activities, it did remind me of Lewis Carroll.

“Alice laughed. ‘There’s no use trying,’ she said. ‘One can’t believe impossible things.’

I daresay you haven’t had much practice,’ said the Queen. ‘When I was your age, I always did it for half-an-hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.

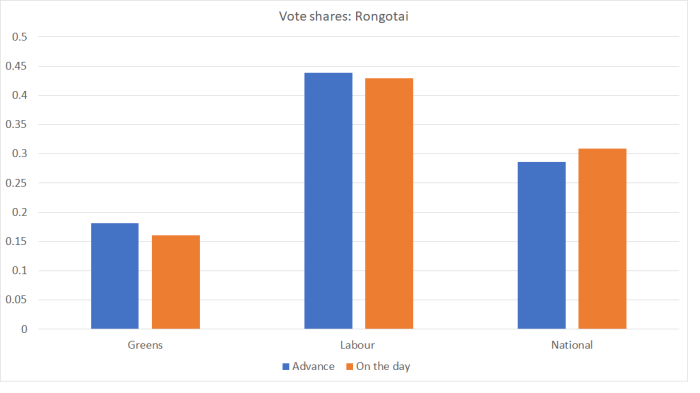

Finny’s article is headed “Time for NZ political parties to take the migrant vote seriously” (actually I was pretty sure Labour had been doing just that in South Auckland for decades), but his focus is on the ethnic Chinese vote, and Jian Yang.

On the last day of the Westie experience [some years ago] I was introduced to a National Party candidate, Dr Jian Yang. He was teaching in the political science department at the University of Auckland. We talked about his academic background, about what he had done in China before leaving for Australia (where he completed his PhD at ANU), about the China-New Zealand relationship and about the Chinese Embassy and Consulate network in New Zealand.

It was clear Dr Yang was very well-connected to the leadership of the Chinese communities in New Zealand, as well as to the Embassy of the People’s Republic of China and its Auckland Consulate. He also had significant connections in China, both to government figures, and to the business community. This was the first of many meetings I have had with Dr Yang. We have met in his context as a MP, as a member of select committees and at social functions. We have travelled together to China and elsewhere as part of official delegations. It is my understanding that Dr Yang has become one of National’s most successful fundraisers, in much the same way Raymond Huo is important for the Labour Party’s fundraising efforts.

Did they, one wonders, back in 2010/11 discuss Yang’s background in the Communist Party and his teaching role in the Chinese foreign intelligence services?

What is astonishing is that one of New Zealand’s most-experienced China experts is, at least in public, untroubled by any of this: the close connections to a foreign government’s embassy, even as he serves as a member of the New Zealand Parliament, or the key role he describes both Yang, and Labour’s Raymond Huo playing in party fundraising? Not that many decades ago, the convention – perhaps not always rigorously observed – was that elected politicians stayed well clear of party fundraising efforts, for good reasons to help maintain the integrity of the parliamentary system.

Finny is in full defence mode for Yang (and presumably Huo).

But it was a strange campaign period, with political players employing various strategies. Among the twists and turns, a rather strange and well-coordinated analysis/investigation was undertaken and then reported by Newsroom and the Financial Times about the past of Dr Yang. Subsequent coverage has led to calls for Dr Yang’s resignation.

Now, I have been involved in politics long enough to know that there are few stories of substance to emerge in the middle of an election campaign by coincidence (particularly ones that are so thoroughly researched). This was a story suggested by someone who had an agenda of some sort – and the timing was intentional.

If 10 days before an election isn’t a reasonable time to ask questions about a candidate’s background. I’m not sure when is? And it isn’t as if, to date, anything those media outlets reported has been disproved or refuted?

And Finny has nothing at all to say about Professor Brady’s paper, the timing of which was determined by the dates of an international conference she was presenting at. As he talks up – no doubt correctly – the importance of the migrant vote, surely suggestions that a major foreign power might be actively engaged in attempting to control most of the local Chinese-language media, and Chinese cultural associations, might have been worthy of some mention? These people are, after all, voters in our system, and our system allows new arrivals to vote much sooner than any other democracy.

I’m sure Finny is well aware of all this stuff, and is probably well able to distinguish the stronger bits of Professor Brady’s case from any that might be more questionable, or which might require more evidence to confirm. But nothing, not even a word. Would saying more have queered the pitch in terms of his future professional dealings?

Of course, if so, he isn’t the only one. Those master-classes MFAT is promoting had a number of eminent speakers. Some are current public servants and they, of course, must serve the government of the day. But most weren’t. And, of them all, the only one I’ve seen engage openly on the issues, and potential/actual threats Professor Brady raises, is Geremie Barme. And he’s Australian.

I’ve been critical of much our mainstream media for their lack of ongoing or substantive coverage of either the Jian Yang issue, or the more general influence-seeking activities Professor Brady describes. But you might have supposed that the Chinese-language media would be agog with the stories. In fact, I asked a fluent Chinese speaker about that. That person found that other than in Epoch Times (an anti-communist network of papers – including a NZ version – based in the US, apparently with some Falun Gong connections) there has been little about the Jian Yang story, and nothing at all about Professor Brady’s paper.

As Brady notes

New Zealand’s local Chinese language media platforms (with the exception of the pro-Falungong paper 大纪元/The Epoch Times) now have content cooperation agreements with Xinhua News Service, get their China-related news from Xinhua, and participate in annual media training conferences in China. Some media outlets have also employed senior staff members who are closely connected to the CCP. As part of Xi era efforts to “integrate” the overseas Chinese media with the domestic Chinese media, New Zealand Chinese media organizations are now also under the ‘guidance” of CCP propaganda officials.

The (lack of any) coverage of her paper and its claim would appear to consistent with her story.

And lest there is any doubt about the sort of regime the rest of the world faces in the People’s Republic of China, I thought this Reuters story on internal censorship in the modern age was a good place to end. It tells of a flash private company in China, full of eager young “auditors”, scouring the web for material to delete, anticipating/implementing the Chinese government-Party edicts. Here, it seems, all too many of our government and opposition politicians, our academic and business elites, and too much of our media seem all too ready to do the same. Whether it happens through naivete, a misreading of New Zealand’s economic exposure to China, the influence of private business interests, political fundraising opportunities, post-political opportunities, sponsorship deals, access, some combination of these, or whatever, it isn’t what we should accept in a free and democratic society.