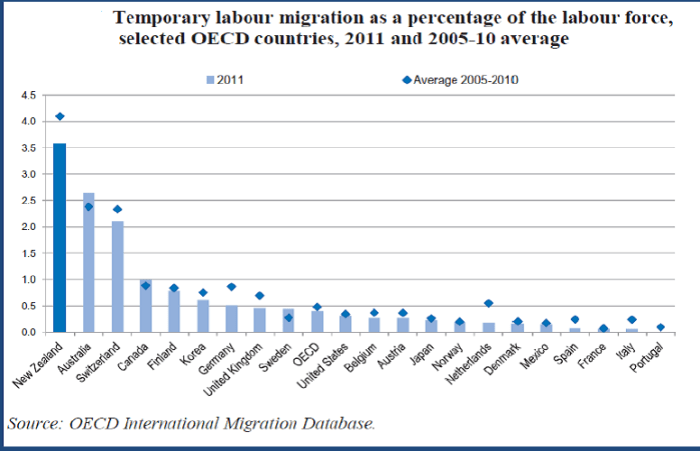

New Zealand has one of the very largest planned and managed active legal non-citizen immigration programmes of any country anywhere. Individual EU countries sometimes have larger legal inflows – but mostly they can’t control intra-EU flows – and in recent times the illegal inflows (some mix of refugees and economic migrants) to some countries have been very large. Immigration is a big issue in the UK Brexit debate, but immigration to the UK is on a much smaller scale than that to New Zealand.

Cross-border flows in conflict zones are often high – and an unwelcome, if second best, outcome all round. Most of the Syrians who have flooded into Lebanon, Turkey or Jordan would prefer to be back home in a secure Syria. The Lebanese, Turks, and Jordanians would no doubt prefer that too.

As I’ve noted recently, the United States issues green cards at a rate about a third the (per capita) rate New Zealand grants residence approvals. Canada – a much richer country than New Zealand – has just increased its target migrant intake, but in per capita terms it is still less than New Zealand’s. The only advanced country I’m aware of that sets out to (and succeeds in) attracting more migrants, per capita, than New Zealand is Israel, and their circumstances are quite different for two key reasons. The first is geopolitical, in that population could well prove critical to the future existence of the state of Israel. And the second is about the founding conception of the state of Israel as a Jewish homeland – the Law of Return allows any Jew (and some descendants) to migrate to Israel, and grants immediate citizenship to those who do.

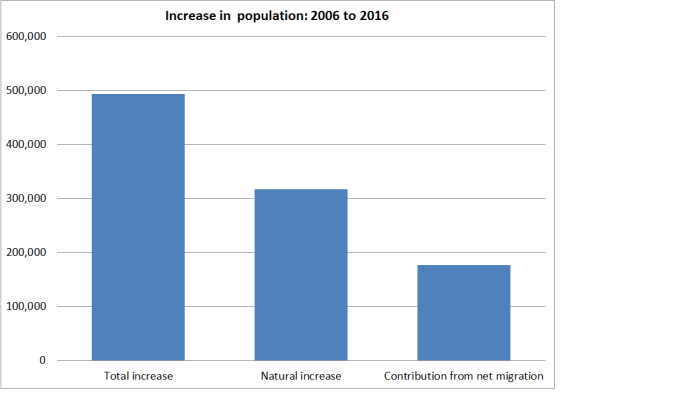

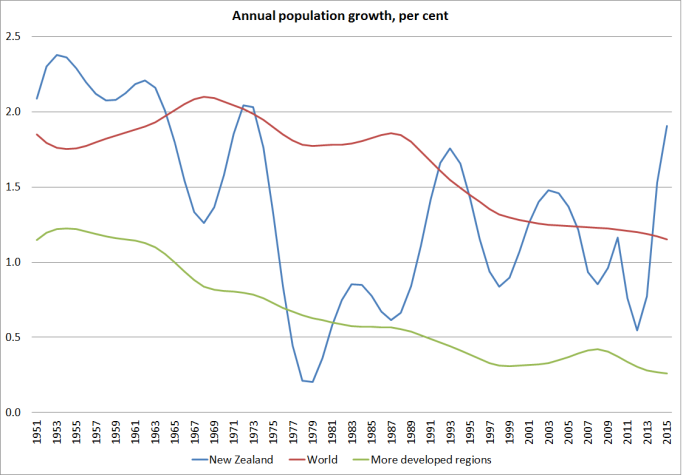

We are an outlier. We have total control of our borders, no geopolitical threats to our existence, and no sense of New Zealand as the historic homeland for some ethnic or religious group scattered across the earth. And yet we bring in huge numbers of non-citizen migrants each year. The anomalous nature of our approach is heightened when it is remembered that people who know New Zealand, and its opportunities, best – ie New Zealanders – have been leaving in large numbers for decades. Oh, and ours is an economics-based programme, and yet our long-term economic performance just keeps on being pretty disconcertingly poor.

I know most of the theoretical arguments for immigration (and emigration). But this isn’t a theoretical argument about some abstract stylized country. It is an argument about the appropriate role, and effects, of our particular immigration policy, faced with the specifics of this particular country at this particular time in its history. Theoretical models can be helpful in thinking about the issues, but only in so far as they capture the key relevant features of the New Zealand economy. On my reading, few do.

And so I’m always keen to see the strongest cases that people can make for our unusual immigration policy, in a New Zealand specific context. Hand-waving accompanied by citing papers that take a global perspective doesn’t shed much light on the particulars of New Zealand’s situation. The government’s chief economic adviser, the Secretary to the Treasury, simply asserts there are economic benefits from immigration, but has made no attempt to demonstrate how they arising in the specific context of New Zealand. His perspectives often seem more relevant to the British debate – recalling that is only about six or seven years since he moved here from the UK. Neither Treasury nor MBIE’s advice – in formal publications or in material released under the OIA – provides much to engage with.

There is a bureaucratic/academic elite consensus around the key elements of the immigration programme. But the other key source of support is the business community. Mostly they’ve favoured large scale immigration for decades – through periods of overfull employment and of uncomfortably high unemployment. Throughout those decades, New Zealand’s relative economic performance has continued to deteriorate. Perhaps they think – if they stopped to analyse the issue – we should just be thankful we avoided the counterfactual – who knows how bad our living standards might now be if, say, our population had increased by perhaps 50 per cent over the last hundred years (as in a typical Northern European country) rather than 300 per cent?

Various representatives of the business community have been out this year championing our immigration policy. I’m not suggesting that all of them support every detail of how the current system is working, but the general message seems to be that we are on the right track – running such an unusually large immigration programme, even though our productivity performance remains disconcertingly bad.

A few months ago, I wrote about a brief contribution to the debate from Roger Partridge, the chair of New Zealand’s premier business-funded (typically non-tradables business funded) economic think-tank. Running under the heading Immigration Grows the Pie, it wasn’t a long piece but it was typically forthright:

And that is not the end to the good news. Countless international studies have shown that increases in immigration not only tend to increase jobs, but also to increase the prosperity of the host nation. We benefit from their productive endeavours, their ingenuity and their diversity. And the more skilled the migrants, the greater the benefits.

That there are gains from immigration has received cross-party support in New Zealand since at least the 4th Labour Government. Let us hope the anti-immigration demagoguery falls on deaf ears. Going down that path we all lose.

The challenge is not keeping out the migrants; it is keeping out the bad ideas. Luckily, that does not need a wall, just clear thinking.

But, as Partridge acknowledged in subsequent comments, none of those “countless” studies focused on the specifics of New Zealand’s situation.

And then in the last couple of weeks, as the immigration debate has received a bit more attention, the Dominion-Post has run advocacy pieces from the leaders of two business advocacy or lobby groups.

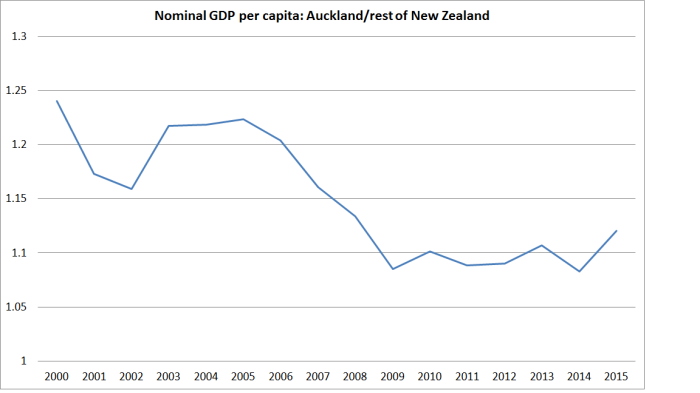

On 10 June, the chief executive of BusinessNZ, Kirk Hope, was out with a column headed – at least in the hard copy – Don’t stem the immigrant tide (there is an identical piece on the BusinessNZ website, under the more subdued heading Improve immigration for the long-term). Hope has form – I highlighted another one of his op-eds earlier in the year which celebrated our GDP growth rate as among the higher in the OECD, while never once mentioning that rapid population growth was such that recent per capita growth had been quite disappointing by international standards.

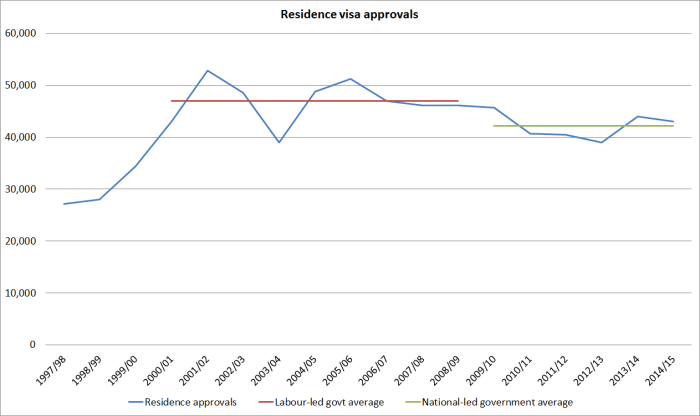

In his latest piece, Hope takes issue with calls to cut our residence approvals target.

Immigration is in the news again – being blamed for Auckland’s housing problems, with suggestions that immigration should be drastically cut, to around say 10,000 new permanent residents per year, to restrain Auckland house prices.

The numbers involved –with roughly 30,000 new permanent residents settling in Auckland a year alongside a current shortfall of about 30,000 houses in Auckland – would seem to support the suggestion.

But the suggestion doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

Reducing the quota to 10,000 would not by itself solve Auckland’s housing problem, and would bring problems of its own.

Restricting immigration as proposed would harm the economy.

With a birth rate just above replacement level, an ageing population and baby boomers retiring, we need immigrants to sustain the economy and pay for our superannuation, just as in decades past.

And that seems to be his main argument. It isn’t a very persuasive one.

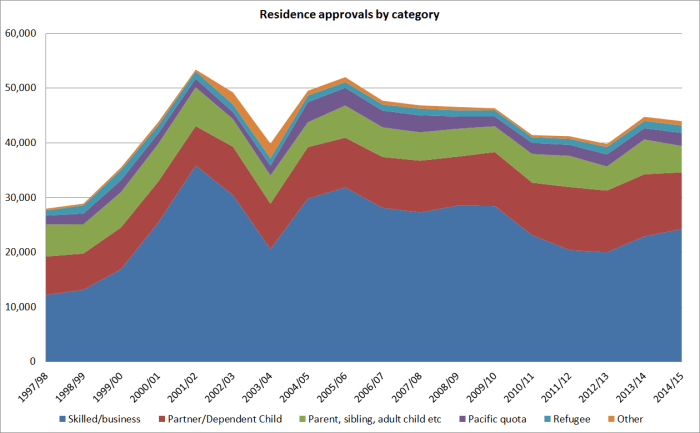

On the immigration side of the story, around 10 per cent of residence approvals are under the “parent” heading – ie mostly people who are already quite elderly themselves, and won’t be making much contribution to paying for NZS. Another 1000 or so will be refugees. I don’t have any problem with us taking refugees, but the evidence suggest refugees struggle to match New Zealanders’ earnings and employment rate even decades after arriving here. And unlike the systems in many countries, immigrants themselves are entitled to the full NZS themselves after only a relatively short time living in New Zealand – ten years.

And on the NZS side of things, if there are affordability challenges with the current system, we have it in our own hands to modify the system to make it more readily affordable. We could raise the age of eligibility – National knows it needs to happen, even if the Prime Minister has pledged not to, and Labour campaigned for a higher age at the last election. Other countries have made these sorts of changes. We could also age-index NZS eligibility. We could modify the entitlements of those who haven’t spent most of their working lives in New Zealand. And there are other options I don’t support, but which would also ease the fiscal pressures, such as income and asset testing, or linking NZS increases to prices rather than wages. And we can keep the way open for more older people to stay in the labour force for longer – on the count, we already have one of the least distortionary old age pensions systems anywhere. We are quite capable of managing the pressures ourselves.

Large scale immigration might make a small difference to NZS affordability, but it is an awfully big intervention for a really quite small difference. As it is, New Zealand’s birth rate is around replacement, unlike many European and Asian countries, so the ageing population issues are in any case less pressing here than in most places.

In the end, the best way to support the various social spending commitments society wants to make is to foster a highly productive economy. We’ve kept on failing to do that, and while immigration policy almost certainly isn’t the whole story, there is no evidence whatever that high rates of immigration have improved the position.

The NZS affordability argument seemed to be the sum total of the BusinessNZ case. In his article, Hope goes on to suggest some refinements to the current system

The jobs being filled by temporary work visas right now are mostly chefs, dairy farm workers and carpenters, showing the current growth points in the economy: tourism, dairy and construction.

There’s no problem using migrants to fill these current needs – but they are not necessarily the needs of the future.

Our aspiration for the future is to grow businesses and industries in high value areas – engineering, high tech manufacturing and services, digital technologies and high value addition to primary products.

We should be welcoming new permanent residents who have skills relevant to these areas to help these sectors to grow.

If he just means that we should be putting more focus on highly-skilled migrants then – subject to the current overall target continuing – I’d agree with him. But it is curious to see the leader of a business group reckon that he knows what skills and what industries will be the ones that will prosper in a future, more successful, New Zealand. And it is puzzling to see so little faith placed in the workings of the labour market, or the skills and capabilities of New Zealand. It is redolent of some sort of 1960s indicative planning mentality – the sort of line of argument I have previously criticized MBIE for.

Successful economies don’t need lots of migrants. In some cases they might welcome them anyway, but in others not. As I’ve noted previously, the United States was at the peak of its economic and political dominance during the decades when it was taking very few immigrants at all. I’m not suggesting a causal relationship (in which the US prospered because it cut back immigration) simply that it wasn’t obvious that high immigration was a necessary part of economic success.

Kirk Hope’s article was followed yesterday by an article from John Milford, the chief executive of the Wellington Chamber of Commerce, under the (hard copy) heading “Skilled migrants a win for us all”.

His evidence appears to be a recent MBIE National Survey of Employers. Asked their views on the impact of immigration, employers responded as follows

It isn’t an ideal piece of information. After all, MBIE – the people commissioning the survey – are also the key official champions of immigration policy, and the administrators of the system. And even setting that to one side, we don’t know how many people disagreed, and how many didn’t answer or didn’t know.

But even setting those points to one side, I’m not surprised at all that individual employers answered along the lines indicated in that chart. For an individual employer, the ability to choose a migrant for a particular vacancy increases that employer’s choices at the wage rate being offered. Indeed, in some sectors – one could think of aged care nurses – the wage rates might be sufficiently low that most of the suitable applicants might well be immigrants from poorer countries with lower reservation wages. But the ability to fill a particular vacancy says nothing at all about whether immigration policy is working to serve the longer-term economic interests of New Zealanders. And nor would individual employers have any particular expertise in evaluating the arguments in that regard. It is a lot like the idea that immigration eases skills shortages. For an individual employer, facing a specific hiring decision, the ability to recruit an immigrant may well ease that employer’s specific “skill shortage” (ie prevent the wage offered having to rise) but for the economy as a whole, large scale immigration increases resource pressures, it doesn’t ease them. New Zealand economists knew that decades ago.

Back in the 1950s and 1960s many New Zealand employers probably also thought that manufacturing protectionism was good for New Zealand too. It might well have been good for many of them individually, but it wasn’t good for the longer-term living standards of New Zealanders.

Business sector advocates often try to have us believe that key sectors just couldn’t survive without reliance on large scale immigration. Set aside the inherent implausibility of the argument – how do firms in the rest of the world manage – and think about some specifics. Sure, it is probably hard to get New Zealanders with alternative options to work in rest homes at present. So, absent the immigration channel, wage rates in that sector would have to rise. Were they to do so, I can see no reason why in time plenty of New Zealanders would not gravitate to the sector. It was New Zealanders who staffed the old people’s home my grandparents and great aunts were in 30 years ago.

Same goes for the dairy sector, or the tourism sector. As one former senior MBIE person put it to me a while ago, what reliance on migrant workers in dairy has done is mostly to enable dairy land prices to be bid a bit higher than otherwise. Raise the wages and New Zealanders will, over time, gravitate to the opportunities in the sector. That is how labour markets work.

Of course, none of this is obvious to an individual employer. They probably can’t raise their wages to attract New Zealand workers instead, even if they wanted to. To do so would undermine that particular firm’s competitive position. But again, this is the difference between an individual firm’s perspective, and a whole of economy perspective – and the latter should be what shapes national policy. Cut back the immigration target, along the lines I’ve suggested, and we’d see materially fewer resources needing to be spent on simply building to keep up with the infrastructure needs of a rising population. We’d see materially low real interest rates, and with them a materially lower exchange rate. The lower exchange rate would enable New Zealand dairy farmers, and tourism operators, to pay the higher wages that might be needed to recruit New Zealanders into their industries, and probably still be more competitive than they are now. And plenty of New Zealanders now working in sectors totally reliant on an ever-growing population would, in any case, be looking for opportunities in other sectors.

Perhaps some readers might think I’m being unfair to Partridge, Hope, and Milford. After all, no one can cover all their arguments in a single article of a few hundred words. As readers know, I certainly can’t. But surely the best, and most robust, arguments would be put forward first in high profile pieces?. And what they’ve offered us doesn’t look very robust or convincing at all. It feels like either a high level application of general international theory, without thinking about the specifics of New Zealand, or an individual employer’s view of the world – where the ability to hire more people, on the day, at much the same wage is always going to feel like “a good thing”, no matter what the macroeconomic implications might be. I really hope some of the advocates of the current policy can make the effort to put together a more sustained case for how New Zealand’s current large scale immigration – or even their preferred refinements to it – has really been working to lift productivity and the medium-term living standards of New Zealanders.

Of course, there are people on the other side of the argument, even some fairly eminent ones with some serious business backgrounds. Don Brash spent 18 years as a private sector CEO before turning first to public policy and then politics. No one can accuse Don of being some of nativist, or of having even a shred of doubt about the benefits of an open economy. Don published his memoirs a couple of years ago, and included some chapters on various policy issues. One of those chapters was devoted to issues around immigration, including some of the earlier versions of the arguments I was raising. Don concluded

I’ve been reluctantly forced to the conclusion that, if we want faster growth in per capita incomes and a lower balance of payments deficit, among the policy measures we need to take is a much more restrictive attitude to total inwards migration

Commenting further

…employers in the export sector who benefit from employing immigrant workers may themselves carry some of the “blame” for the high real exchange rate which makes their lives so uncomfortable

The current government has, during its term, commissioned two external panels to report on issues to do with New Zealand’s disappointing economic performance. Don Brash chaired the 2025 Taskforce, and Kerry McDonald chaired the 2010 Savings Working Group.

McDonald started his career as an economist, spent time as director of the NZIER, and then moved into the corporate world, spending decades as chief executive of Comalco. He continues to sit on various corporate boards. This week he came out with a fairly trenchant piece on the failings in the New Zealand political and policy process. I didn’t agree with it all by any means, but here is what this economics-trained senior business leader had to say about immigration.

The high rate of immigration is a national disaster. It is lowering the present and future living standards of New Zealanders by serious adverse economic, social and environmental consequences.

The critical criterion for policy is impact on the living standards of New Zealand residents. The impact on the immigrants is irrelevant. But, the political view is a simple and misleading “quantity” based one – more immigrants means population growth and more jobs, houses and infrastructure spending, so GDP increases. This suggests a strong, well-managed economy – which is a nonsense in New Zealand’s case with an export dependent economy.

In terms of national benefit the “per capita” impact is the important one. Unless immigrants increase New Zealand’s exports and foreign exchange earnings and savings per capita, or bring particularly valuable skills to the economy, they simply impose substantial additional costs on and reduce the living standards of New Zealand residents.

Having a job, even in an export industry or tourism, is not enough, and many immigrants lack the particular, high level of skill and productivity to add the necessary value. Using them to fill low skill, low productivity gaps in the labour market, eg. building houses for our excess population (other than on a temporary basis), is damaging to New Zealand’s interests, in the short and long term. So, we scramble to build more houses and ignore the fundamental policy problems.

As I say, I don’t agree with everything he says, but at very least his is a robust honest recognition that, whatever the glee club says, things aren’t going well for New Zealand, haven’t for a long time, and that current policy – perhaps including immigration policy – and political leaders have to take some considerable measure of responsibility for that.

Note: The x axis is scaled so that each marker is ten times the magnitude of the previous one.

Note: The x axis is scaled so that each marker is ten times the magnitude of the previous one.