Back in early October I wrote a post “Public policy just keeps on worsening”, on the then newly-announced Residential Development Underwrite scheme, under which the government will provide free downside price/liquidity insurance to big residential property developers, for a period that was said not to be forever but with no specific time limit, and instead with confident assurances from the minister (Bishop) that the government (Cabinet) would judge when to turn this subsidy off and on. It seemed like a classic example of bad policy, playing favourites at the big end of town, offering subsidies with no rigorous analysis of any sort of market failure, handing unconstrained discretion to ministers, and so on.

All this was stated to be being done with the primary objective of “maximising overall housing supply, while minimising the risk and cost to the Crown”. On which I noted in the earlier post

You minimise the cost and risk to the Crown by simply not offering free insurance, and if you must offer such insurance you should do so with a disciplined and transparent model (to, for example, estimate the economic price of the option). But there is nothing of that sort in any of the MHUD material, just a lot of mention of the (extensive) discretion afforded to officials, of whom we may be left wondering both what their expertise is and what their incentives are. Why would we back them to make better choices than financial market participants? And as for “maximising housing supply”, there seems to be no analytical framework there either, including around incentives on developers (who will, of course, prefer free insurance and can be expected to try to game the rules). Will there be any material impact on supply, will any impact be any more than timing, and how will MHUD rigorously evaluate claims put to them by developers? Oh, and isn’t developers finding themselves with overhangs of houses and land part of the way that much lower house prices actually come about?

I ended that post this way

It is a rather sad reflection of how the quality of New Zealand policymaking has fallen. Perhaps we should be grateful that exchange rate cycles aren’t what they were – and that past governments were less prone to scheme like this – or who knows what sort of free insurance the government would be dreaming up for exporters.

Who knows what the relevant government agencies thought of this scheme. I’ve lodged OIA requests and am particularly interested in any analysis and advice from The Treasury and the Ministry for Regulation.

You might have thought an arbitrary and apparently inefficient intervention like this would be grist to the mill for that new “central agency” the Ministry for Regulation, an opportunity to show any microeconomic chops they had. Instead, like true bureaucrats, they took a full 20 working days to reply to my OIA request to tell me that the new ministry had undertaken no analysis and offered no advice related to the Residential Development Underwrite scheme.

But I suppose I should be grateful they only took 20 working days (note that the law does not automatically give agencies 20 working days: the standard is “as soon as reasonably practicable). The Treasury, by contrast, took 40 days, insisting that they needed time for “consultations”.

Their full response is here:

Treasury OIA reply re Residential Development Underwrite scheme Dec 2024

There were only five papers. Two were from after the scheme was announced (operationalising the required ministerial delegations). The first two aide memoires were from January and February respectively in response it appears to advice from the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development, concerned about a possible “hard landing” in the housing construction market, and picking up on discussion of underwrite schemes that had been put in place as part of the ill-fated Kiwibuild scheme.

This is from the first of those aide memoires, dated 17 January

That is a pretty astonishing paragraph. Neither here, nor anywhere else in the papers, is there any attempt to justify a claim of “market failure”, and while we can all agree that government land-use restrictions have created and exacerbated many problems in the housing and urban land market they aren’t in any meaningful sense “government failures” either, but rather choices which governments could undo if they chose. And nothing in the first two sentences provides any serious or analytical support for the third sentence, apparently supporting fresh interventions. (There is of course little doubt that government interventions can affect the level of activity in particular markets, but the question is the robustness of the case for any such interventions.) That last sentence is also perhaps a bit puzzling: isn’t a subsidy to private developers going to add to private construction activity (not crowd it out?) and how are the efficiency and value-for- money tests even plausibly met when guarantees are handed out for free?

Carrying on through the papers we find this snippet

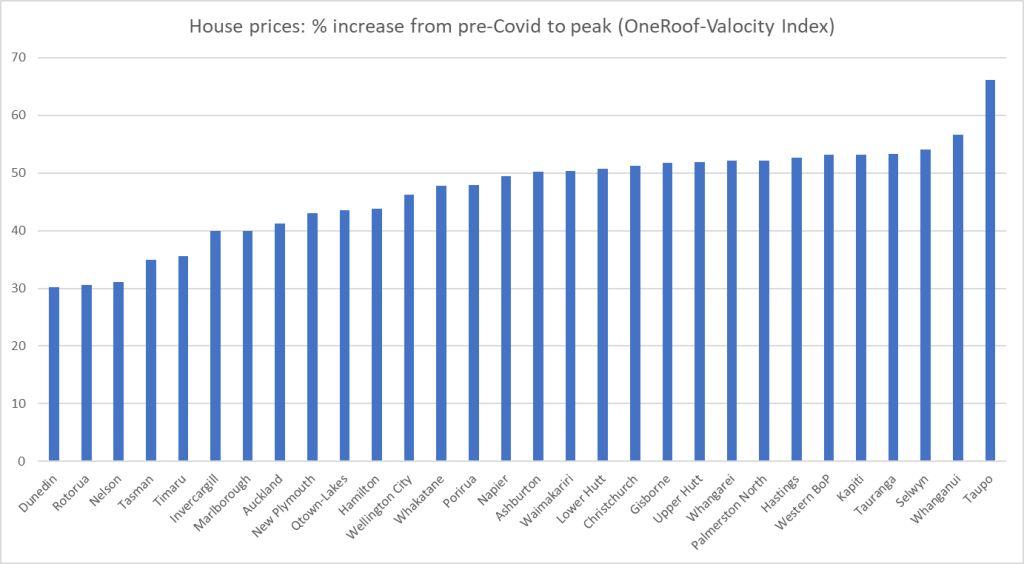

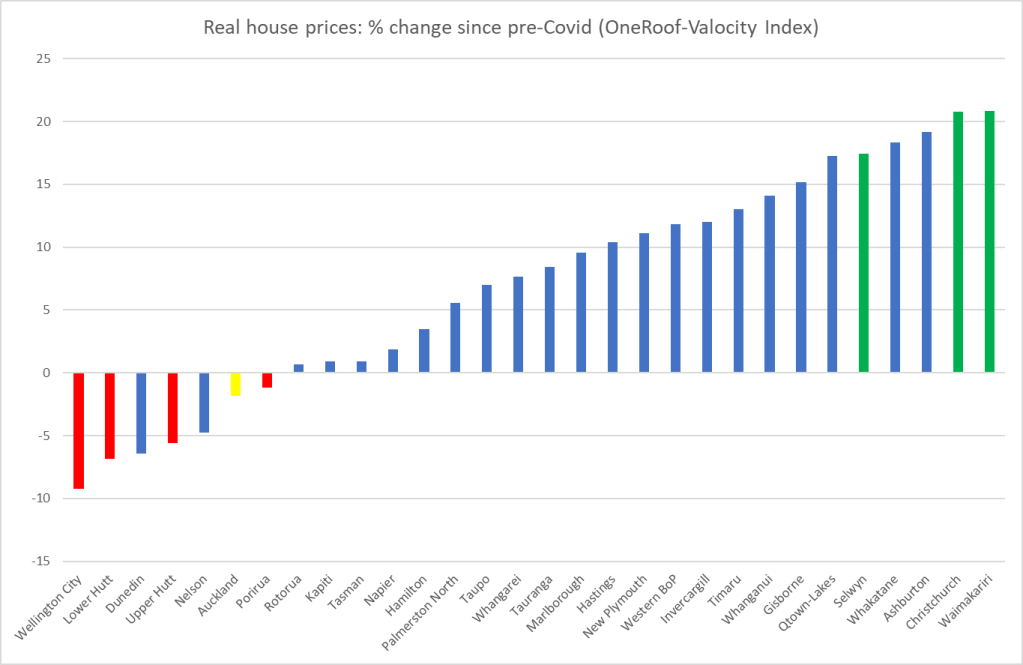

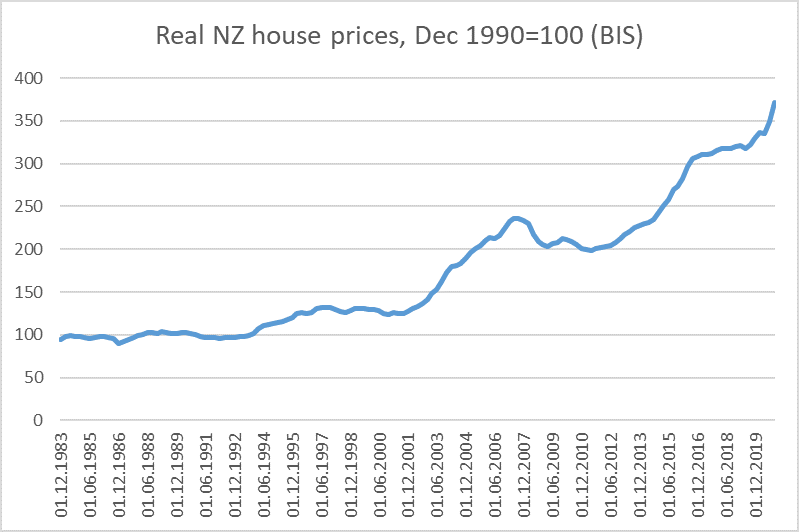

Really? Our Treasury thinks a mitigant is that bad underwrites can simply be stuck in the bottom drawer in the hope that one day something will turn up…. And here one thought a wider goal of a housing reform process was permanently lower real house prices.

And these from the 16 February aide memoire

But there is no robust analysis anywhere, including not scintilla of analysis leading us to believe that Treasury had thought hard and robustly about why judgements of officials and ministers were likely to be better than those of private financiers, including reflecting hard on the incentives facing the two groups. Perhaps this is more of an example of ‘government failure’.

But what is perhaps more surprising still is that those notes were written in January/February, and then there is nothing released (or withheld) until the next document, which is dated 3 October. The Residential Development Underwrite scheme was announced on 4 October.

There are several things interesting about this aide memoire

- (rather trivially) Treasury has withheld, as out of scope, more than half of the title of the aide memoire, only to release the title in full in their letter to me

- much more substantively, the paper is dated 3 October, and is described as being for a meeting with the Minister of Housing on 7 October. The paper goes on to note that, as far as Treasury understood things on 3 October, “the RDU will be announced before the end of October”. It was, of course, announced the following morning.

- and perhaps most remarkably of all, the substance of the RDU section of the aide memoire is just slightly more than one page, and is really all process oriented, and answer one detail question from the Minister of Finance about scope for changing the parameters once the RDU was in place.

In other words, assuming (as we must) that the OIA has been answered honestly, there was no Treasury advice at all on the specific development of the RDU, or any of its parameters, and the scheme itself was rushed out far more quickly than The Treasury had understood just the day before the actual announcement.

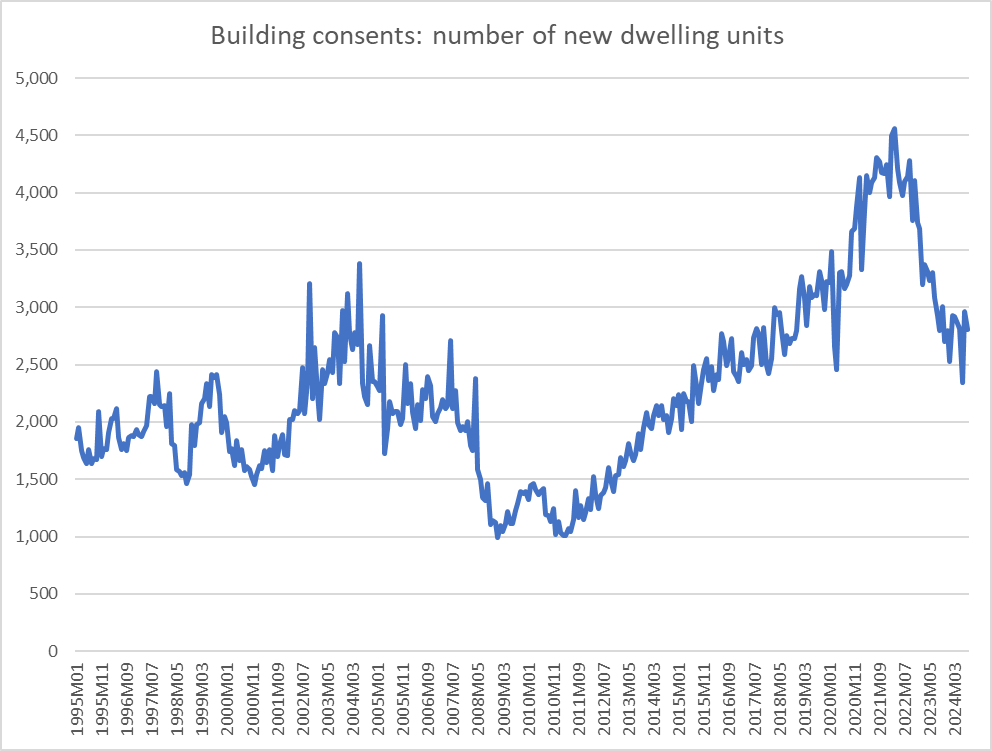

It is a poor and unnecessary policy, underpinned it appears by a poor policy process, a central planners’ mentality (government knows best how many houses should be built etc) and a cast of mind from The Treasury that seems astonishingly more sympathetic to big-end-of-town corporate welfare handouts and ministerial discretion than would have seemed even remotely plausible in the heyday of The Treasury. And perhaps, as is the nature of so many of these sorts of interventions, many economists are suggesting that the residential building approvals cycle was already bottoming out even before ministers and bureaucrats rushed out their shiny new subsidy toy.