Readers will recall that the New Zealand China Council was set up by the government a few years ago, and is largely funded by the government, to promote

deeper, stronger and more resilient links between New Zealand and China

The Council includes the heads of government departments/agencies (MFAT and NZTE), and includes plenty of people – including retired politicians – with strong business links to the People’s Republic of China. A significant part of what they do – see their Annual Report – is a “communications and advocacy programme”, designed – it seems – to help ensure that as far as possible New Zealanders see things their way, and don’t create trouble around either the character of the regime (and the party that controls it), or that regime’s activities at home, abroad, and in New Zealand itself. There are, after all, deals to be done, political donations to be solicited, friends to be protected, and so on.

Stephen Jacobi is the executive director of the Council, and its public face. In the last few weeks I’ve written about a speech Jacobi gave recently in which he attempted – without much depth or rigour – to bat away concerns about PRC activities and risks, and also about a rather economics-lite press release he had put out attempting (Trump-like) to make much of the current trade surplus with the People’s Republic of China.

This week Jacobi was out with another speech, this one on Investing in Belt and Road – A New Zealand Perspective. “Belt and Road Initiative” (or BRI) is the most recent label (previously “One Belt, One Road”) on a somewhat ill-defined but expanding PRC programme, partly about improved infrastructure (initially in and around central Asia) and partly – some argue mainly – about extending PRC geopolitical interests in ways that display scant regard for recipient countries’ debt burdens, social or environmental standards, transparency and so on. A few weeks ago, a Bloomberg story reported that Xi Jinping had just added the Arctic and Latin America to the areas (now almost the entire world) supposedly cover by the Belt and Road initiative

Or as a recent New Yorker story put it

“Across Asia, there is wariness of China’s intentions. Under the Belt and Road Initiative it has loaned so much money to its neighbours that critics liken the debt to a form of imperialism. When Sri Lanka couldn’t repay loans on a deepwater port, China took majority ownership of the project”

I’ve also linked previously to a recent report on the potential debt risks associated with the BRI programme.

Last week’s speech isn’t, of course, the first time Jacobi has been talking about the BRI. In a Newsroom article last year he was quoted this way

Jacobi says “the real play” in our corner of the world is less about infrastructure and more about connecting up with China through including the flow of goods, services and people.

“I’ve even heard reference to the Digital Silk Road, the vision is expanding … there’s a bit of talk in China about Belt and Road being a new way to manage globalisation instead of the old ways, which have been done off the back of trade liberalisation in particular.”

But it wasn’t very clear, at all, what it meant for New Zealand

Jacobi says New Zealand shouldn’t let too much time go by before it develops more concrete ideas for what Belt and Road could achieve in New Zealand.

“We’ve really got to move from a very conceptual phase to talking about more definite projects: I can see scope for some projects that exist at the national level between New Zealand and China on bigger picture economic cooperation-type matters, and I can see scope for more discrete projects with individual provinces.”

But what did Mr Jacobi have to say this week?

He mightn’t be sure quite what the substance of the Initiative is, but Jacobi seems pretty sure it is a good thing.

Meanwhile China under its newly-empowered President is proceeding to implement the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as a new model for globalisation, precisely at the time when people all around the world are calling for new ways to make globalisation work better.

What China – with far-reaching restrictions still in place on foreign access to its market, especially around services – means by “globalisation” isn’t what most people think of.

And so he tells us that

It is the assessment of the NZ China Council that New Zealand cannot afford to stand aside from developing a contribution to Belt and Road.

If we choose not to engage, others most certainly will and we will find our preferential position in the Chinese market further eroded.

There is the odd caveat

At the same time, we need to proceed carefully and in a way which matches our interests, our values and, especially, our comparative advantage.

although I don’t think I noticed any substantive discussion of our values or what they might mean in this context.

The context for any New Zealand involvement is a Memorandum of Arrangement signed by the two governments a year ago.

As Jacobi puts it

The MoA is non-binding and largely aspirational – it set a timetable of 18 months for the development of this co-operation – we understand the official wheels are now in motion to put some greater flesh on the bones of how we might co-operate in the future.

And the China Council is working up its own ideas.

We suspect the greater benefit for NZ is likely to be in the “soft infrastructure” rather than the “hard infrastructure” – the way goods, services, capital and people move along the belt and road rather than building the road itself.

New Zealand has wide policy expertise and commercial services to offer in this area which matches a number of the policy areas China has highlighted for Belt and Road including policy co-ordination, investment and trade facilitation, and cultural and social exchange.

And they’ve had a consultant’s report done – to be released in May – with proposals.

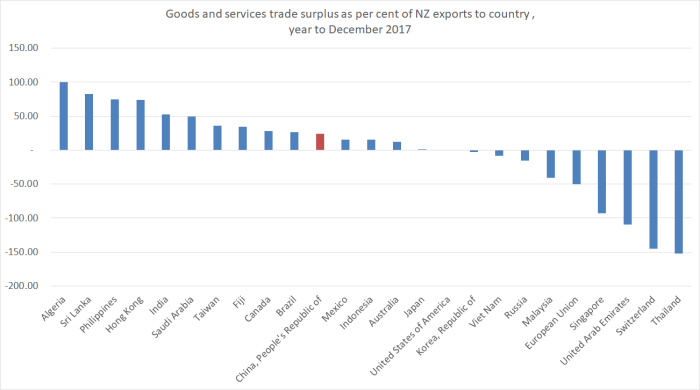

Count me a little sceptical. When Statistics New Zealand released the country breakdown of goods and services exports a few weeks ago, I had a look at the services exports of New Zealand firms to the PRC. Under services exports – themselves only 20 per cent of the total – were tourism, export education, and travel/transportation. Fifth on the list of “major services exports” was “other business services”. Last year, that totalled $32 million – a fraction of 1 per cent of total exports to China. It isn’t surprising, given that tight restrictions China has on most services sector trade, but it does leave you wondering what Mr Jacobi has in mind from his champion of globalisation.

I hadn’t previously got round to reading the Memorandum of Arrangement. On doing so, it was hard to disagree with Mr Jacobi’s “aspirational” characterisation. But equally, one had to wonder whether these were aspirations we should share (with Simon Bridges, who signed the agreement for the previous government).

It was, for example, a little hard to take at face value this bit of the preamble

and a bit further on the preamble started to get positively troubling, the Participants

I’m quite sure I – and most New Zealanders – have little interest in pushing forward “coordinated economic…and cultural development” with a state that can’t deliver anything like first world living standards for its own people (while Taiwan, Singapore, South Korea etc do) and whose idea of cultural development appears to involve the deliberate suppression of culture in Xinjiang, the persecution of religion (Christian, Muslim, Falun Gong or whatever), the denial of freedom of expression (let alone the vote) and which has only recently backed away from compelling abortions. And that is just their activities inside China. “Fusion among civilisations” doesn’t sound overly attractive either – most of us cherish our own, and value and respect the good in others, without wanting any sort of fusion,and loss of distinctiveness. But perhaps Simon Bridges saw things differently?

The next section is “Cooperation Objectives”. There is lots of blather, including this

Hard not to think that “regional peace and development” might be better secured if the PRC forebore from creating new articial islands, seizing reefs etc in the South China Sea, or patrolling menacingly around the Senkaku Islands, engaging in military standoffs with India, or even making threatening noises about Taiwan. There seem to be two main threats to regional peace, and the other is North Korea. But you’d never hear anything of that sort from a New Zealand government.

The next section is “Cooperation Principles” under which the governments agree to

In other words, if New Zealand keeps quiet and never ever upsets Beijing, whether about their domestic policies (economic, human rights, democracy), their foreign policies (expansionist and aggressive) or their influence activities in other countries, including our own, everything will be just fine, and the PRC will keep dealing with us. And on the other hand…….?

There are then five “Cooperation Areas”. Apparently, we are going to actively conduct “mutually beneficial cooperation in….public financial management” (hint: that “wall of debt” is a sign things haven’t been done well so far). But the one that really caught my eye was under the heading “policy cooperation”, where Simon Bridges committed us to

It isn’t obvious New Zealand now has any “major development strategies” (see sustained lack of productivity growth) or that the PRC ones offer much to anyone – well, individual business deals aside – when compared with, say, those of Taiwan, Singapore, or Korea. And what is this bit about strengthening “communication and cooperation on each other’s major macro policies”? Why? To what end? And who thinks it is desirable for New Zealand to “connect and integrate” our (largely non-existent) “major development strategies”, and our “plans and policies” with those of the PRC? A country that, as even Mr Jacobi recognised in his earlier speech, has fundamentally different values.

And the agreement concludes

One has to wonder how it is in the interests of the people of New Zealand (as a whole – as distinct perhaps from some individual businesses looking for a good deal), or consonant with their values, to support such an initiative, or a regime such as that of the PRC. Apart from anything else, it all seems curiously one-sided: the agreement isn’t to support New Zealanders, but rather to advance a geopolitical projection strategy of a major power, with very different values than our own. Can anyone imagine us having signed such an agreement with the Soviet Union in the 1970s?

We can only wait and see the details of what the China Council will propose in their paper in May. And, even more interestingly, what the government comes up with – being bound to formulate a detailed work plan by September. Winston Peters may regret the previous government signing up, but he is now stuck with the agreeement for four more years. One hopes the government will find a way to some minimalist, not very costly, arrangements, but given how keen governments of both major parties have been to cosy up to Beijing – party presidents praising Xi Jinping – it is difficult to be optimistic. On the other hand, it is difficult to see quite what any New Zealand involvement might amount to, and perhaps Beijing has already had the real win – getting a Western country, a Five Eyes member, to sign up to such a questionable deal with such an obnoxious regime.

But to get back to Mr Jacobi’s speech, nearing the end he observes

There is currently a debate in New Zealand about the extent of Chinese influence in our economy.

I am on record as being concerned about some of the “anti-China” narrative in that debate, especially in the unfortunate targeting of prominent individuals in the Chinese community, but there is nothing wrong with a debate focused on how to build a resilient relationship with China given the difference political values between our two countries.

While I welcome his final half-sentence, it is a little hard to take seriously when he never – at least in public – engages seriously with the concerns that people like Anne-Marie Brady have been raising. As I noted about his earlier speech, among other things he will simply never

- address why it is appropriate to have as member of Parliament in New Zealand a former Chinese intelligence official, former (at least on paper) member of the Communist Party, someone who now openly acknowledges misrepresenting his past on forms to gain entry to New Zealand (apparently because that is what the PRC regime told people to do),

- address the PRC control of the local Chinese language media, and associated (and apparently heightened) restriction on content,

Instead he falls back on plaintive laments about the “unfortunate targeting of prominent individuals in the Chinese community”. These same people – since presumably he has in mind Jian Yang and Raymond Huo – sit on his own advisory board. And both are not members of the public, but elected members of Parliament: not in either case elected by a local constituency (and certainly not by “the Chinese community”), but by all New Zealand voters for their respective parties. And yet both of them – but particularly Jian Yang – simply refuse to answer questions or appear in the English language media to explain and defend (in Yang’s case) the background, and their ongoing ties to the PRC and apparent reluctance to ever say a critical word about that heinous regime.

It must now be six months – since the Newsroom stories first broke – since Jian Yang has appeared. At the moment, it looks much less like “unfortunate targeting”, than quite specific and detailed targeting, with unfortunate defence and distraction being played by key figures in the New Zealand establishment, including Mr Jacobi. Perhaps people might be more persuaded by Jacobi’s case – that working closely with, and constantly deferring to, the PRC was in the best long-term interests of New Zealanders, if he called for his board members to front up, rather than giving them cover to simply shut up.

In concluding the post a few weeks ago about Mr Jacobi’s earlier speech, I had a speculative paragraph on some uncomfortable parallels between the PRC now, and Germany in the 1930s. If the parallel isn’t exact – and we must hope not, given how the earlier episode ended – it still seems closer than any other historical case I can think of, including the same desperate desire to appease, to understand, to get alongside (key figures in the British Cabinet were still hoping to do economic deals with Berlin well into 1939), and the same reluctance to confront evil or take a stand (even at some cost to some businesses). In a week when the PRC “Parliament” passed the amendment to remove the term limit on the office of President with 2958 votes in favour and two against, I decided to check out the results of the referendum Hitler staged in August 1934 after President Hindenburg died, to finally concentrate all power in his own hands. This was 18 months into the Nazi era. Despite widespread intimidation, almost 10 per cent of voters (on a high turnout) felt free to dissent

| For | 38,394,848 | 88.1 |

| Against | 4,300,370 | 9.9 |

| Invalid/blank votes | 873,668 | 2.0 |

| Total | 43,568,886 | 100 |

There is something to be said for our governments openly and honestly confronting the nature of the Beijing regime. We can’t change them, and it isn’t our place to, but we can choose with whom we associate, we can choose how often we just keep quiet, and how much of our own values (and the interests of many of our own Chinese citizens) we compromise in the quest for a few deals for a few businesses (and universities) – and a steady flow of political party donations. And we can, and do, as I’ve pointed out before, make our own prosperity. If individuals firms want to deal with the PRC, on its terms, then good luck to them I suppose, but we then need to wary of those same firms and institutions, and to ask whose interests they are now, implicitly or explicitly, championing.

There is a weird line in Matthew Hooton’s column in today’s Herald in which he asserts that no one should be critical of China because “China is just doing what emerging Great Powers always do”. That may be a semi-accurate description. It didn’t stop us calling out, and resisting, the expansionist tendencies of Germany, Japan, or the Soviet Union. It shouldn’t hold us back in recognising the threat the latest party-State, the People’s Republic of China, poses both abroad and here.