We’ve all seen or heard of the sort of parent who has a troubled teenager or young adult but who is always making excuses for, or minimising, the child’s repeated bad behaviour. Yes, yes, that [insert specific] was wrong, but really s/he is a good girl/boy. Parental love is, as it should be, a powerful force (mostly for good) but in those cases the indulgence and excuse-making rarely ends well.

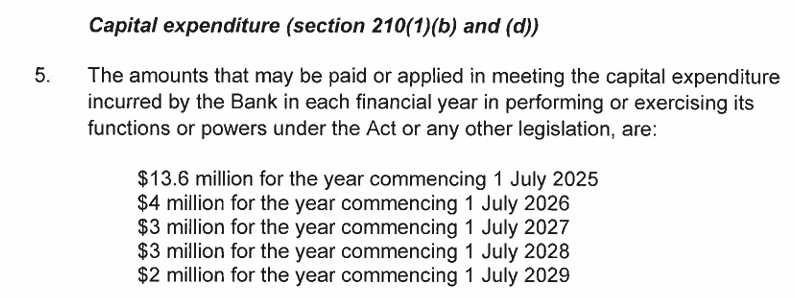

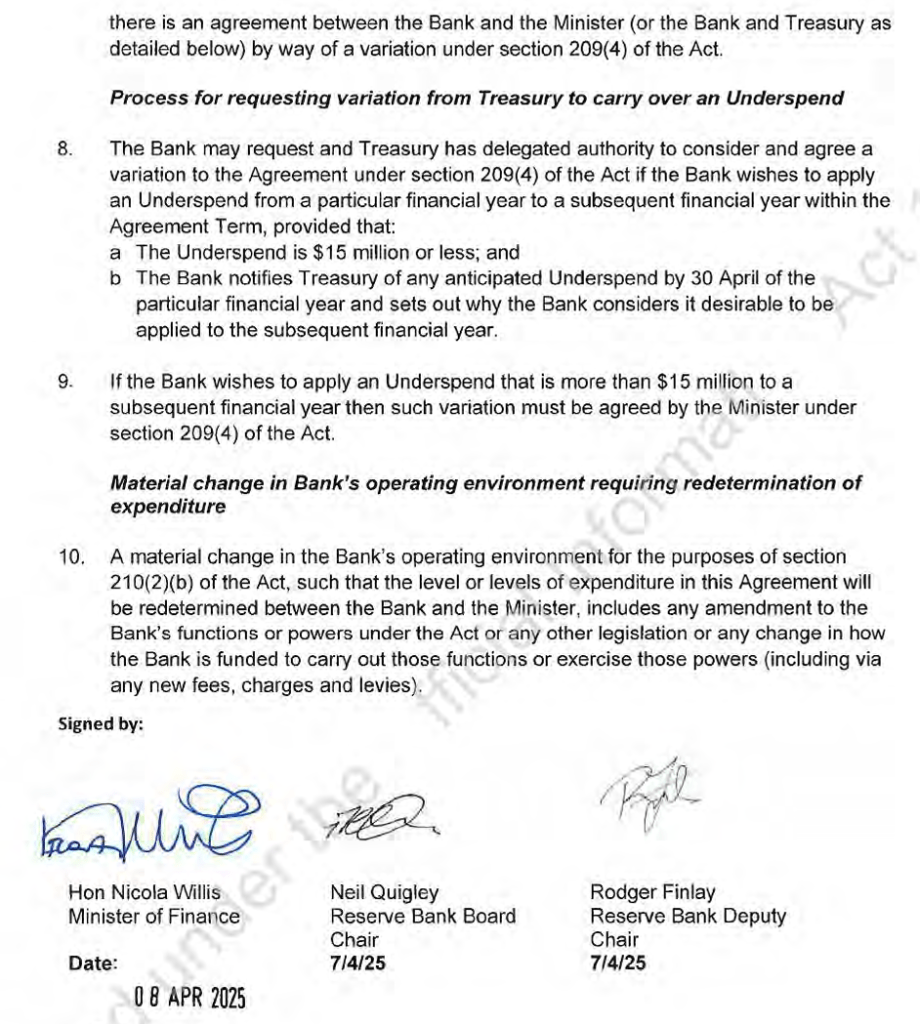

It was a parallel that came to mind in thinking again about the extraordinary way in which Nicola Willis has indulged Neil Quigley, the chair of the of Reserve Bank Board, in which role he now seems to have had more lives than the proverbial cat. No one seems to understand why she reappointed him to one last two year term as chair last year (having already been caught out actively misleading Treasury and the public, and having accommodated pretty all of Orr’s own excesses, policy and behavioural, and uneasy relationship with the truth). And things have only gone downhill from there. The same week Quigley’s reappointment was announced, he released the Bank’s 2024/25 Statement of Performance Expectations which included an operating spending budget far in excess (23% in excess) of spending allowed to the Bank for that year in the last year of the old Funding Agreement, as amended by Grant Robertson just prior to the last election. When they had sought comment from the Minister on the draft SPE (as the law required them to) they simply failed to tell the Minister how much they proposed to spend – and it appears that neither she nor Treasury thought to ask (in their defence, presumably they implicitly assumed that the Bank would simply operate consistent with the Funding Agreement limits).

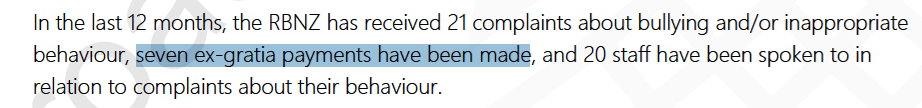

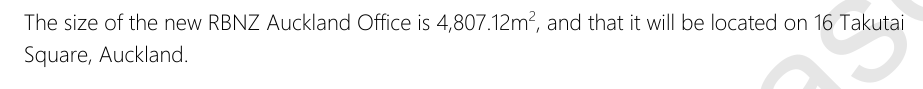

Then they – Quigley, Orr, and the rest – used that egregious budget not only to lock in fancy new and big long term office space in Auckland, to keep driving up staff numbers, but also as a base for their bid for spending for the next five years, all the while claiming their bid was quite consistent with the Minister’s expectation (as I noted on Wednesday, it seems that on the letter of what MoF had said it was – she and Treasury probably assumed they were dealing with decent and honourable people – but in spirit and substance it was anything but). They were eventually knocked back, but staff (lots of layoffs) and taxpayers (restructurings cost) are paying the price. The Board members, notably the chair, remain in office.

And, of course, it was capped by the extraordinary dishonesty of the last six months around the departure of Adrian Orr (I used to say “on 5 March” but it turned out yesterday he’d already been out of the office for a week prior to that) in which Quigley has – from the moment the first press release dropped – been actively misleading the public about what went on, attempting to block scrutiny, and (as revealed the other day) deploring Treasury’s compliance with the Public Records Act in writing a moderately-expressed file note of a major policy meeting between senior Bank and Treasury people and the Minister of Finance. Once again, it was too much for the Minister of Finance (and this time Labour’s finance spokesperson joined in), but….. Quigley (and the rest of the Board, and the governance of the Bank is vested in them collectively not in Quigley individually) is still there, even though his position as chair is one that Minister can remove him from more or less at will.

I won’t bore readers by tracing through all the chaotic litany of active misrepresentations we’ve been subjected to (and yes “litany” there was meant to evoke Peter Mahon) over the six months, through press statements claiming it was just that inflation was down and it was time to go, denial that there were any policy or conduct issues, claims that Quigley still had confidence in Orr, then the 11 June statement which again actively misled the public, through to yesterday’s new (and still selective) timeline. But just an example, compare and contrast his interview with Heather du Plessis-Allan little more than a month ago with the story revealed in yesterday’s release (which, incidentally, further confirms the story I first reported here from the anonymous insider who leaked to me). We have been misled and obstructed, deliberately, from day one – by someone who reveals repeatedly a disdain for public scrutiny and accountability, let alone the law when it might inconvenience him. Almost singlehandedly (although don’t forget Hawkesby and the rest of the Board) Quigley has materially furthered damaged the reputation of an institution already badly diminished by the now-departed Governor (who’d been lying to FEC the very morning he’d lost his cool at Treasury, forcing Quigley to apologise for at least the second of those). It is, frankly, scandalous that Quigley is still in office. A growing number of observers, not just those with a specialist in the Reserve Bank, seem to be reaching the conclusion that his position should be untenable.

It was, I think, the Taxpayers’ Union whose statement on Wednesday (ie before even yesterday’s release) which best captured for me what the repeated inaction says of the Minister of Finance herself.

This is a major and very powerful public institution. The Board is put in place by the Minister to serve taxpayers’ interests in governing the institutions, but they seem to have driven a cart and horses through any sense of acceptable standards (whether around the spending or the attempts to obstruct and cover up in recent months). The institution is diminished, the standing of the individuals (notably Quigley) is diminished, and the Minister of Finance – responsible to Parliament and the public for the Bank – does nothing beyond disclaiming all responsibility and occasionally wringing her hands and wishing that her recalcitrant or rogue chair would only behave a bit better. What sort of Minister of Finance does that make her? She (and Treasury) was played for a fool herself, and she has let the public be repeatedly lied to. An effective minister would have dished out condign punishment months ago. From Willis, nothing.

Quite why is anyone’s guess. Perhaps she is just grateful that Orr is gone (aren’t we all?) and the board did help trigger that. Perhaps there is something about the medical school – would it reflect badly on the government if they now ousted as chair the chap they’d just given a controversial medical school to? Some claim it is that Quigley is a National partisan (I don’t take that one very seriously. He might fancy himself as a political operator – though as Jonathan Milne’s profile a couple of months ago noted, people who’ve been on boards with him don’t think he is very good one – but….he was reappointed as chair as recently as 2022 by a Labour government). There are, of course, still substantial unanswered questions about the Minister’s own involvement in, and knowledge of, events leading up to the Orr resignation announcement (and Quigley and the Bank are clearly still covering for her, with no mention in any of their releases regarding contact with the Minister or what she was advised or, and aware of, when). But it all reflects very poorly on her, including associating – the Minister of Finance – with a sequence of events which has left the standing and authority of the nation’s central bank in the gutter, and with Quigley still responsible for wheeling up the nominee to be next Governor – and if the Minister accepts Quigley’s nominee, that person’s standing will be tarred from day one.

Quigley should have gone long ago. But he should go now. He should do the decent thing and resign. But if he (still) won’t, the Minister should not have any hesitation in removing him, certainly as chair, and probably as a board member too (the standard there is tougher, but clearly met).

For the rest of this post, I want to (a) step through the legal provisions, and b) address any concerns that somehow removing Quigley (and, possibly, other board members, especially those from 2024) would be in some sense Trumpian (with his current attempt to fire Lisa Cook from the Federal Reserve Board of Governors). It wouldn’t. These bits are for reference/reassurance and anyone who simply wants to take my word for what can be done can easily stop here.

Legal Provisions

In many government entities, board members can be removed more or less at will. That isn’t so with the Reserve Bank, a conscious choice made in overhauling the Act in 2021, presumably reflecting the key policy role the Board has around financial system regulation and supervision. One can debate the pros and cons of that model, but the law is what it is.

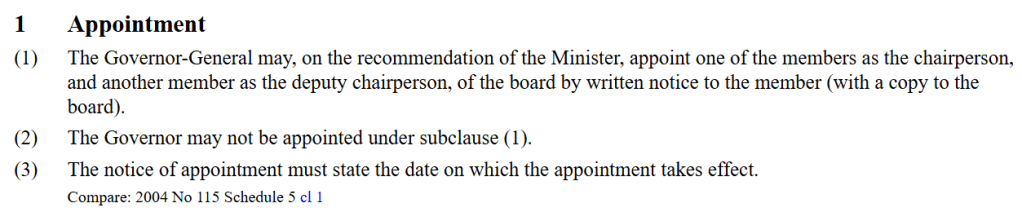

Take the chair’s position first. The chair and deputy chair are directly appointed from among board members by the Minister

There is no requirement to specify a term for the appointment, although Willis reappointed Quigley last year explicitly for what was envisaged as a final two year term.

And if the chair (or deputy chair) can’t be removed instantly, in substance it is pretty close

The Minister is not required to specify a cause and can act once she has consulted with the person affected.

Removing Quigley as chair would still leave him as a member of the Board.

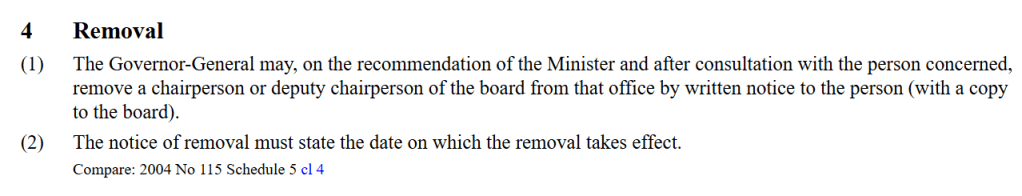

There is a tougher test to be met to remove a board member. Here is what the Act says.

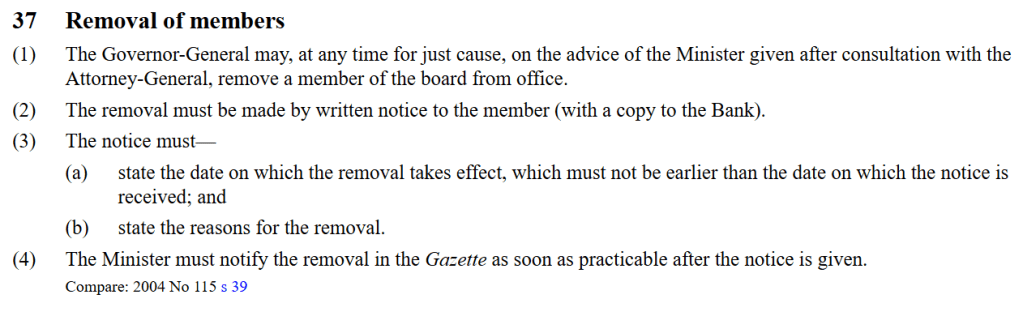

And here are the relevant bit of their duties. First, the collective ones

And these are from the individual duties

The Act is also pretty clear that the duties are owed to the Minister. For example

It would seem not difficult at all to remove Quigley from the Board altogether on multiple grounds including (a) not operating in a manner consistent with the spirit of service to the public (his disdain for legitimate public interest and scrutiny has been manifest and explicit on numerous occasions), b) not operating with honesty and integrity (in the coverup of the last six months), and c) in threatening non-collaboration with Treasury unless they defied the Public Records Act, and d) in not operating in a financially responsible manner (setting that 24/25 budget so far in excess of what was allowed for that year, and associated locking in property spending that could be warranted only if somehow the government had made something like that level of expenditure permanent, something for which he had no reasonable grounds to believe was likely to happen. But quite probably if Quigley was removed as chair, or stepped down voluntarily or under duress, he would not want to see out the last nine months as an ordinary board member again.

I reckon there is a pretty reasonable case that all the remaining 2024 board members could also be removed, since they have either supported or done nothing to stop, the decisions and behaviours described above. Probably the only board member in the clear is former Deputy Governor Grant Spencer who only took office in early July this year (although with each passing week of Quigley’s conduct and the Bank still providing only partial information his position is weakened), with Philip Vermeulen a marginal case (he was an observer – “future director” – last year, but became a full director on 13 February this year). I think there is a strong case for removing the deputy chair Rodger Finlay and Byron Pepper (both of whom had earlier ethical issues around their appointment) and Jeremy Banks and Susan Paterson, but I guess a) it isn’t likely to happen, and b) you would need a strong bench of replacements straight away. But it is a choice open to the Minister.

Lisa Cook comparisons

President Trump has, of course, been looking to oust members of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. For now, he seems to have given up on the chair, Jerome Powell, but this week has (purported to) dismiss Lisa Cook, justifying it on the grounds of alleged misrepresentations (of the sort that, if true, could be fraudulent) relating to mortgage applications she had lodged before becoming a Governor.

People can and will debate the merits of the issues, and the legal one is likely only to be decided by the Supreme Court determining what “for cause” means in the context of the Federal Reserve legislation. But it is pretty clear that Trump wants more influence – direct, or through chosen appointees – as regards monetary policy decisions. Unsurprisingly, that is controversial and can be seen to go towards the heart of central bank operational independence, which has become a hallmark of most advanced country central banks in recent decades.

Quigley’s position (or indeed that of the other board members) is quite different in a number of ways.

In terms of policy/economic substance, the most important difference is that Cook is a monetary policy decisionmaker (all members of the board of governors have permanent positions on the decision-making FOMC). Quigley – and the Board – are not. Monetary policy decisions in New Zealand are made by the Monetary Policy Committee consisting of the Governor, three other internals, and three externals. The Board’s role is to (a) nominate MPC members, including the Governor (but the decision is finally the Minister’s and Cabinet’s) and b) to monitor and review their performance (since the Board can advise removal if MPC members breach their individual or collective duties). The Board does have important independent policymaking powers in respect of financial system regulation (eg bank capital requirements are a board policy decision now), and given the government’s expressed preferences re some of the banking regulatory issues there might be some queasiness about removing board members…..if it were not for the fact that their performance on quite other well-documented matters (and especially that of the chair) evidently rose to the standard for removal.

And that sentence is the other main point. We – and the RB – are not operating under decades-old legislation with fuzzy language around removal powers, but under brand new (2021) legislation, explicitly designed to ensure (a) that the chair is readily removeable, and b) that all board members are explicitly accountable to the Minister for their performance of their individual and collective duties, with removal an explicit remedy open to the Minister in the event of (serious) breaches.

The coincidence in timing with the Trump activities is unfortunate, but – frankly – the debasement of our institutions while the Minister wrings her hands and does nothing about egregious behaviour of the sort we’ve seen is, for want of a better word, more Trumpian (much more so) than taking breaches seriously and acting accordingly to signal that we will insist on high standards from those running our government agencies. That we will sweat the small stuff and (as this become) the big stuff.

Failure to act (specifically on Quigley) is a terrible signal from the government, both of the weakness of its own senior minister and (suggestive) of an indifference to high standards in public life.