A while ago I stumbled on the report of Kristy McDonald QC, dated 22 February 2022, which had been commissioned by Hon David Clark, then Minister of Commerce, into aspects of the appointment of the default Kiwisaver providers, and specifically around the handling of conflicts of interest involving the then chief executive of the Financial Markets Authority (FMA) whose brother-in-law was the chief executive of one of the providers. The FMA provided a strictly limited bit of advice to the Minister.

I was less interested in the specifics of the case - which didn’t reflect very well on the FMA or its board/chair, but was (from the report) hardly the worst thing in the world - than in Ms McDonald’s observations on conflicts of interest. This is probably the most useful excerpt from her report (the document mentioned in italics is from the Public Service Commission).

There is a heavy emphasis on three things really. First, avoiding actual conflicts of interest. Second, ensuring that outside (“fair minded”) observers can be confident that decisions have not been improperly influenced. And, third, documentation, documentation, documentation (which helps demonstrate, at the time and if necessary later, that actual and apparent conflicts have been recognised and dealt with appropriately). As McDonald notes in 6.22 you’d think considerations like these should be particularly important in a regulatory agency, especially one - such as the FMA - with regulatory responsibilities in the financial sector. This is from the very top of the front page of the FMA’s website

You’d really have hoped that the Financial Markets Authority would have gone above and beyond in setting and applying standards for its own people, But…..no. You might remember them banging on a few years ago about “culture and conduct” in the private financial sector. I guess those were aspirations for other people. One hopes that, in the light of the McDonald report, the FMA has now lifted its game in handling such issues in its own organisation. One might hope…..

One of the classes of financial product/entity that the FMA has regulatory responsibility for is superannuation schemes. It has particular responsibility now for a class of so-called “restricted” schemes, closed off to new members and generally in multi-decade run-off. One of the FMA’s predecessor entities was the office of the Government Actuary which had in times past been required to consent to any changes in superannuation scheme rules. In old-style defined benefit superannuation schemes - a form of deferred remuneration where the effects (contributions/entitlements), even for an individual, stretch over decades – those sorts of protection and oversights, whether embedded in statute law or in the deeds of schemes are vitally important. Such schemes are typically established as trust structures in which all trustees are required to undertake their duties with the best interests of members in mind. Being a trustee is, or should be, no small thing, not a duty entered upon lightly.

Conflicts of interest can, at times, be a significant issue. In a typical employer-sponsored superannuation scheme some of the trustees will be elected by members and some will be appointed by the employer. These days - in what is mostly regulatory impost (thank you Key government) – schemes are also required to have a Licensed Independent Trustee. (There were hazy warm thoughts at the time that these might be courageous independent thinkers who’d be a force for good, but the model really seems built more to encourage box-ticking – there are lots of boxes to tick – establishment figures earning a bit of pre-retirement income: you aren’t likely to be appointed to such roles if there is any fear you might rock the boat.)

In a scheme that defers for decades employee remuneration there can be material tensions between the interests of the employer and the members. But much of the time there aren’t such conflicts. The day-to-day responsibility is to ensure that the pensions are calculated correctly and paid reliably, that member queries are dealt with in an appropriate and timely way, that statutory reporting and compliance requirements are met, and that money is collected properly and invested prudently. I’ve been a trustee of the Reserve Bank scheme for 15 years and those issues go by pretty harmoniously, with any differences of view rarely falling along Bank-appointed vs member-elected trustee lines. And if the rules are clear and discretion strictly limited the room for seriously conflicting interests is minimised.

But the differences come to the fore when there is any consideration of material changes to the rules or the status of the scheme. Things are especially problematic if employer-appointed trustees form a majority. That is why, for example, it is common to require regulator consent to change rules and to include protections such that member consent is required from any members who might be made worse off by a rule change (to which they might still consent if, for example, one adverse rule change was balanced by other changes the member considered was to their benefit).

And here the situation is supposed to be pretty clear. A member-elected trustee is not generally regarded as intrinsically conflicted simply by virtue of being a member (since the entire purpose of the trust is to benefit members, whose interests all trustees are supposed to advance). A member-elected trustee can, of course, be specifically conflicted and should then recuse themselves (as an example, it turned out some years after I left the Bank that my retirement benefits from the pension scheme had been materially miscalculated. I stood aside for any deliberations on that matter). But the situation of employer-appointed trustees is generally regarded as different: often they will be senior managers or Board members of the sponsoring employer and the potential conflicts between the interest of the employing firm and that of the trust (and its beneficiaries) can be all too evident.

There is very little regulator guidance on these issues in New Zealand - perhaps not surprising when the FMA hadn’t really handled its own well - but shortly after I became a trustee I found a lengthy guidance note from the UK Pensions Regulator, which I have since regarded as something of a guidepost (it is still current). It is a different country to be sure, but with broadly similar culture, a large DB pension sector, and much of the case law that gets cited here comes from the UK. In any case, the question here is not what is lawful, but what is proper (substantively and in terms of perceptions and appearances).

You might remember that the whole “culture and conduct” tub-thumping exercise a few years back was done jointly with the Reserve Bank. You’d have thought that the Reserve Bank might be some sort of exemplar of good conduct, and concerned to be seen as such. I guess you might have thought that of the FMA too. More fool us.

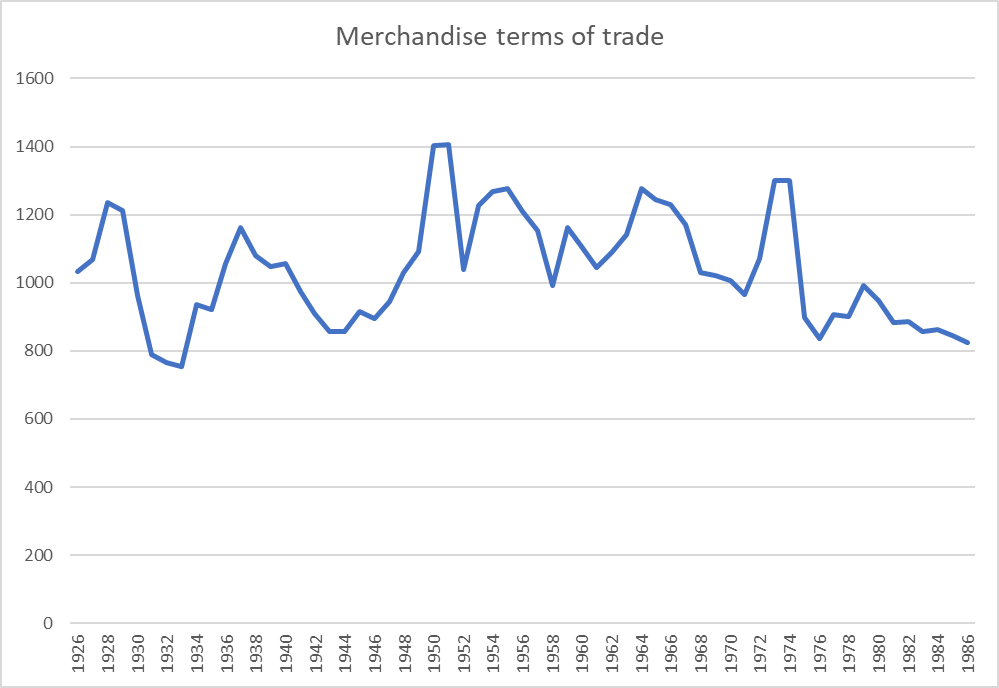

For the last decade the trustees of the Reserve Bank pension scheme have been grappling with arguments and evidence around claims that several significant deed amendments done in the white heat of the reform era (late 80s, early 90s) were not lawfully made and are thus invalid. No one really quite knows what the implications would be if these changes were to be held to be invalid, but it would be unlikely to be good for the Reserve Bank (either reputationally or financially). It would, I think, generally be conceded now that the rule changes were, to say the very least, not handled well by former trustees and management (eminent figures such as Sir Spencer Russell, Don Brash, Suzanne Snively, but also able members’ trustees). In fact, Don Brash himself has raised specific concerns with trustees regarding events on his watch - and trustees simply refused to ever meet him.

Three of the six trustees are appointed by the Board of the Reserve Bank from among directors or staff members (a fourth – the LIT – is chosen by other trustees but long ago declared he never wanted to come between member and employer interests). Those Bank-appointed members can be replaced at will for any reason or none. Over the decade they have included a Governor, a Deputy Governor, a deputy chief executive, a couple of Board members, and a long-serving relatively junior staffer. As we have dealt with the issues over ten years there has never been any sign of these appointees putting member interests first. It is not that nothing has happened - some serious mistakes have been acknowledged and or fixed – but only things that are not awkward or potentially costly for the Bank. It is, of course, impossible to know whether these trustees have actually prioritised Bank interests, but it is impossible to tell apart their actual approach from the sort of approach that would be predicted were Bank interests to be prioritised. Nothing has ever been done to acknowledge the serious conflicts of interest or to document how those conflicts are being managed or dealt with (and the Bank trustees have consistently refused suggestions of either using an arbitrator or approaching the courts for (definitive) guidance and resolution).

Tomorrow morning in Wellington there is a meeting of the members of the Reserve Bank scheme, called by a group of members (including two former senior Reserve Bank managers) under the provisions of the Financial Markets Conduct Act. The members say that they want to seek explanations for the thinking behind various decisions the trustees have made (usually by majority). Rather than engage, it appears that the intention of the Bank-appointed majority is to stonewall. The current chair – one of Adrian Orr’s many deputies - appears more interested in pursuing me for openly articulating my dissent and criticisms of trustee processes and advice than in engaging with members or getting to grips with the substance of the issues. And - par for the course – never seems to recognise any sort of conflict.

I’ve put as much emphasis on atrociously poor processes (in one part of the decade I was moved to describe what was going on as a “corrupt process”, words today’s trustee wanted excised from the version of minutes provided to members for tomorrow’s meeting). But the process problems go back to the start.

Way back when these issues were first raised with trustees, Geoff Bascand - at the time one of Graeme Wheeler’s deputies, with overall responsibility for Bank HR and finance issues - was the chair of trustees. His quick response to the initial approach - itself in the form of a letter and 30 page document- was to suggest, in writing, to trustees that we simply write back to the member who had raised concerns stated that the issue was closed. He sought to reassure trustees that they needn’t worry because even if anyone took legal action trustees were indemnified by the Reserve Bank. Bascand was later Deputy Governor and Head of Financial Stability at the time of the “culture and conduct” campaign.

Things, and processes, were mostly a bit less blatantly egregious after that, but the conflict of interest issue was simply never addressed, and the process was often Potemkin-village-like (expensive, time-consuming, but pretty much working towards innocuous ends). On all hard decisions the Bank-appointed trustees voted for the interests of the Bank……and all of them were left in office by a Bank management and Board that (fully informed throughout) no doubt appreciated their services….in the best interests of members of course, as the law required.

I have written a retrospective assessment of the experience.

The Indifference of the Powerful RBNZ Superannuation and Provident Fund, Reserve Bank, and the FMA

It is probably of most interest to present and past members of the pension scheme, but it is - to me - a fairly egregious example of simply ignoring serious conflicts of interest. The scheme is not itself a regulatory body, but it is sponsored and underwritten by one, and the bulk of its trustees serve wholly at the pleasure of the government-appointed board of another of our financial regulatory agency (Orr and Quigley cannot escape responsibility).

As for the Financial Markets Authority, they’ve displayed almost no interest whatever. I imagine it is mostly a matter of being too small, too hard, and too unglamorous but……this entity’s forerunner (the Government Actuary) actually approved some of the more egregious rule changes, so perhaps turning over rocks would be uncomfortable for them, and of course, the FMA and the Reserve Bank work closely together. You might think that something of a conflict, and a dimension that might mean one needed to be seen to go above and beyond to reassure fair-minded observers. But….this is New Zealand and here you’d be dealing with the FMA and the Reserve Bank.

The latest Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index is, on past timings, due out any day now. No doubt it will repeat the self-congratulatory self-perceptions that are so standard. No doubt too there are many places more corrupt than New Zealand. But maintaining and preserving standards involves sweating the small stuff….or the not so small when they involve key financial regulatory agencies.

UPDATE: As it happens, the Transparency International results were out less than two hours later, with New Zealand slipping out of the top two places. Seems overdue in multiple ways, sadly.