National announced its tax and spending plans this morning. You can read the full 29 page document.

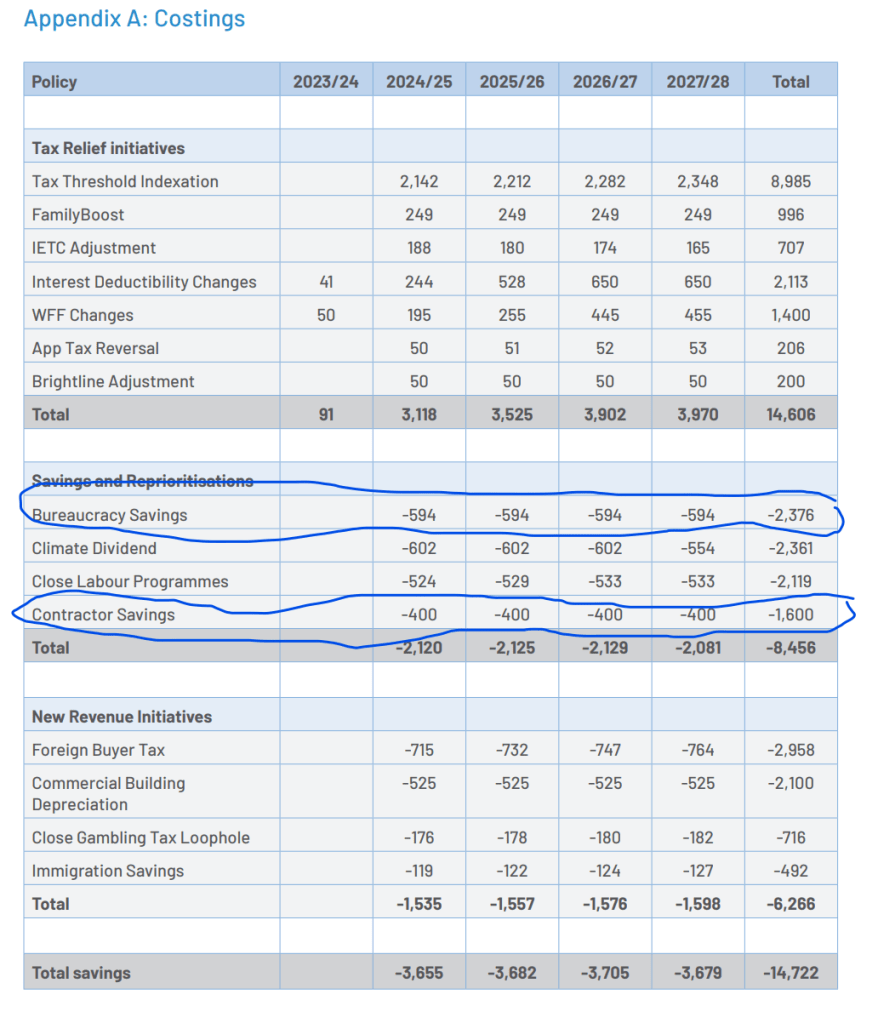

In the way of all parties and bureaucratic agencies these days, everything gets quoted as a four year figure: $14.7 billion sounds like a lot but it about $3.7 billion a year, which is about 0.8 per cent of annual GDP. Cost things over 10 years and you could if you wanted call it a $35 billion plan, with no more or less meaning (and, to be clear, all parties and agencies engage in this headline-inflating exercise).

Today’s plan is sold as being fully separable from National’s fiscal plan, which we will apparently get to see after they’ve had time to digest the PREFU numbers (coming on 12 September). It is a clever wheeze – it seemed to work – in allowing Willis and Luxon to deflect all and any questions this morning regarding the deficit and the possible/eventual/one day return to budget operating balance or surplus. They sold this line on the basis that today’s package was itself fully-funded from new initiatives of one form or another, so that in principle the net impact on what fiscal numbers The Treasury comes up with this package could just be slotted in with no net fiscal effect.

I’m not close enough to any of the line by line numbers to know whether each of them is solidly costed. Their economic consultants say they have been, and (assuming there were no silly mistakes made by accident) National does have a pretty strong incentive to ensure the numbers are each reasonably robust. So, for now, I’ll assume they are (with a few possible caveats about the foreign buyers tax, see below).

But the overall argument – “this isn’t our fiscal plan, come back next month for that” – doesn’t really wash. It might if the budget now was pretty near balance, or even in surplus. No one would, or perhaps should, be very worried about modest changes in a comfortable fiscal position.

But we don’t have a comfortable fiscal position.

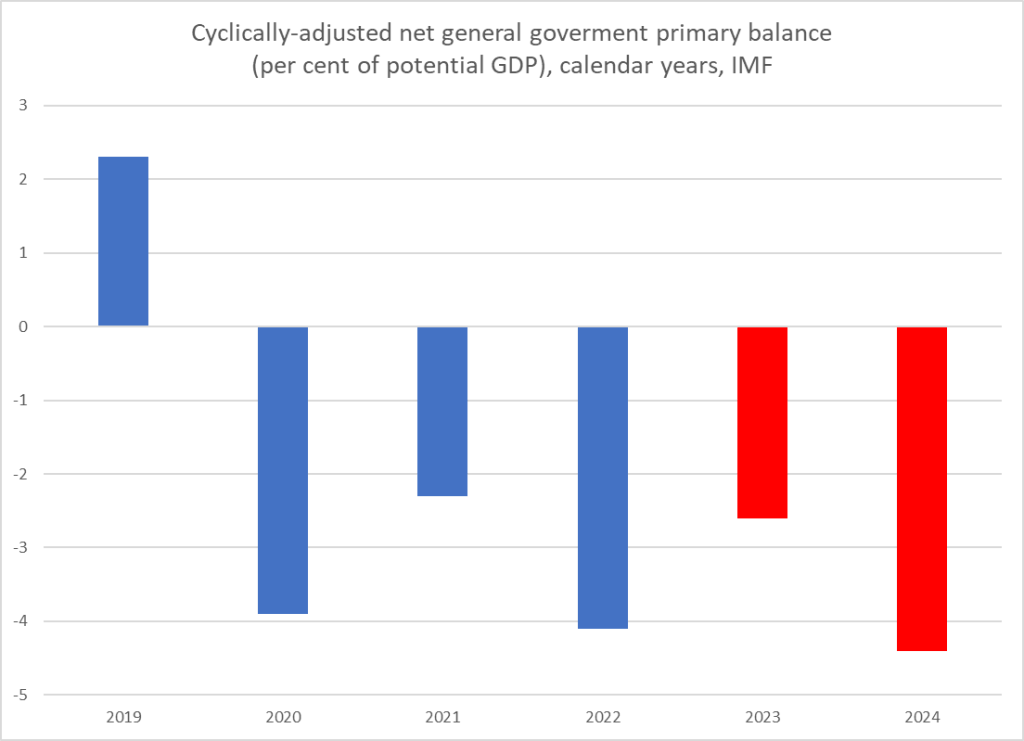

These were the fiscal numbers the International Monetary Fund put out yesterday in their annual New Zealand review

The blue numbers are more or less solid (actual fiscals are, but the cyclical adjustments could still change a bit), while the red numbers – calendar 2023 and 2024 – are going to be heavily influenced by choices and decisions the government has already made. The best advice from the IMF is that no progress has been made in reducing the deficits first run up in the Covid disruption years, even though actual Covid spending is no longer a thing. The Fund includes projections for the further-out years in which the operating balance goes back to respectable surplus for calendar 2027 and 2028, but those are really just assumptions, and don’t rely on specific identifiable tax or spending decisions that would bring about such an adjustment. I should stress that these are cyclically-adjusted numbers, so the ebbs and flows of the economic cycle don’t provide either the problem or the solution. These sorts of numbers led to the IMF recommending – in really quite pointed language for a diplomatic agency talking of a country that has been among the star fiscal performers for decades – “frontloaded fiscal consolidation” and steps to ease the fiscal pressure on monetary policy.

(The government’s control of the timing of the release of the IMF report, kicked to after Monday’s modest fiscal announcement, means these sorts of lines have had almost no media coverage. And of course no one seems to have gone and asked the Governor “what is this fiscal pressure on monetary policy/inflation the IMF talks about; you have claimed in the last two MPSs that there was none?”)

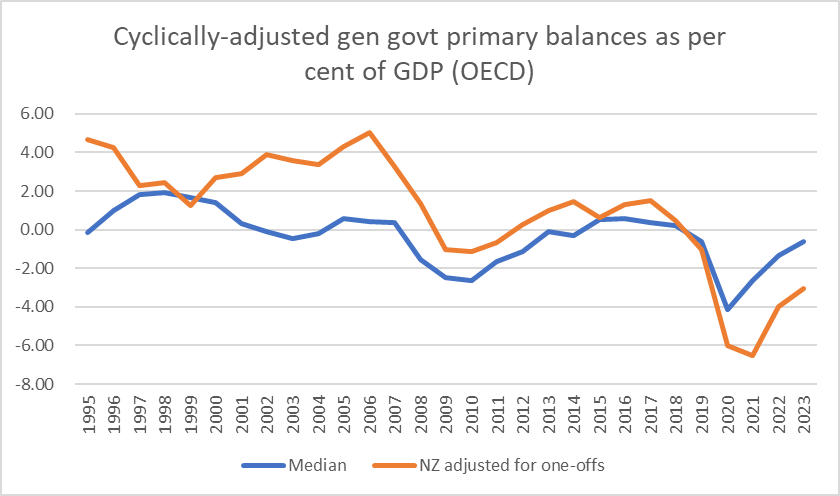

Last week I ran a post here using the OECD’s fiscal numbers. Those numbers will have been finalised a bit earlier than the IMF’s but are available on a consistent cross-country basis. Using that data you can see how large our (cyclically-adjusted) general government deficits now are relative to other OECD countries (and to our own past). The picture of recent years is a little different, but the final year deficit is also large.

Or here (not cyclically-adjusted)

We have a primary deficit that is large in absolute terms, and among the largest in the OECD.

These international comparisons aren’t done on the New Zealand operating balance definition. On that metric, the cyclically-adjusted operating deficit will be a smaller percentage of GDP, but there is little case for a cyclically-adjusted operating deficit (paying for the groceries etc) at all.

These structural deficits do not heal themselves. And while fiscal drag has been a bit of a help in limiting the deterioration in recent years, the forecast return to lower inflation means not even much of that support will be on offer.

Both Labour and National profess allegiance to the idea of an operating surplus…….but seem to have not the remotest interest in telling us what choices they are going to make to get us there. Discretionary choices/adjustments of perhaps 3 per cent of annual GDP might be required.

Today, however, is National’s day. This was their big tax and spending plan. Willis told reporters this morning that “your tax cuts are coming no matter how much Labour proves to have wrecked the joint”. So the tax cuts are iron-clad, and having bitten the bullet – after railing at Labour’s new taxes for years – and put several new tax increases on the table, it is hard to see they are suddenly going to pull a whole bunch more tax increases from their hat a couple of weeks hence to close the deficit.

It is always possible, they could announce some big new expenditure cut – killing off a few big wasteful specific programmes – but it doesn’t really seem in character, and would completely blunt the message from today that “tax cuts are coming”.

It is much more likely that – having announced their big tax and spending plan today – that is largely it. It may be fiscally neutral in its own right, which is better than the alternative of adding to the deficit, but they aren’t going to do anything much about the deficit at all. No doubt Labour won’t either – it will just handwave around whatever the PREFU shows, having cut (with no accountability whatever re eg likely cost pressures) future operating allowances on Monday. It will be a case of “trust us”, without even any credible evidence from either that ‘we know what we are doing” or really care one way or the other. We are at risk of sliding towards the normalisation of operating deficits, of borrowing to pay the grocery bill. The sort of really poor fiscal management you see in places like the United States federal government.

If asked, perhaps National will talk up cutting public sector bloat. I’m sure there is a fair amount to go round (and no one has mentioned the big increase in Reserve Bank spending that the government snuck out last week), but (a) in this morning’s announcement they ruled out a whole bunch of agencies, both because of Labour’s own vapourware announcements on Monday, and because they want any savings redirected to frontline services those agencies provide. That latter might be laudable but it doesn’t represent fiscal savings.

And, in any case, today’s package already relies on unspecific cuts in public sector bloat.

That is $4bn of the $14.6 billion cost of the overall package (30 per cent). I’m not disputing that there are (substantial) savings to be made, but savings made to finance tax cuts (as in this morning’s package) can’t then be used to also close the deficit. Both Labour and National talk of cutting consultant spend. That is cheap talk, unless (a) it amounts to a reduction in total spend, not just taking people onto the permanent staff (shifting the line item, but not changing the total, and b) identifying what work future governments don’t want done.

To the extent there is genuine bloat, the tax cuts package will have grabbed it. To cut further – cut the deficit – they would need to cut deeper and that would mean harder choices, which so far they’ve shown no inclination to be willing to make (nor Labour, but this is National’s day). And all this assumes that cost pressures are adequately captured in current baselines (which I doubt – citing for example the real wage cut forced on teachers despite apparently very real recruitment and retention challenges).

Finally a few thoughts on specific items. Childcare subsidies aren’t really my thing (better to collapse house prices), but both parties seem to like them. I like them cutting back the brightline test tax (less good than abolishing it, but…) and the restoration of interest deductibility for residential rental property owners (like any normal business). On the other hand, there is no commitment to inflation indexing income tax brackets even going forward (if they’d committed they’d have to have costed it).

But what got my goat were the first two of the new taxes.

Is it marginally better to have no ban on foreign buyers buying very expensive houses but having to pay a high tax to do so than to have an absolute ban? I might grudging acknowledge that, but any gain is marginal at best, and it is a policy that David Parker might have dreamed up in a moderate moment. It is an unprincipled revenue grab, which is wildly inconsistent with the party’s rhetoric (mostly good rhetoric) that freeing up the responsiveness of housing supply is what matters, and that we should be encouraging and facilitating more foreign investment generally. And from a party which claims to be – and historically has been – keen on immigration, it just seems weird (conflicting messages) again to not be allowing anyone who moves here, even on a work visa for several years, to buy a house. They are all over the place with barely a hint of philosophical consistency. It is all made more weird by this line from their document in which they seem to argue that their foreign buyer tax policy will itself somehow dampen property price growth.

As for the revenue estimates ($750 million a year), they seem quite high, and the tax rate seems high by most international standards (Singapore is a lot higher). Only time will tell how many people not living here so want a New Zealand house they will pay a 15 per cent tax to do so.

And then there was the other unprincipled revenue grab, the removal of tax depreciation for non-residential buildings. This measure – which increases the tax rate on businesses – was first introduced by National in 2010 to help fund that tax switch package, with no credible or rigorous underpinnings at all. Buildings depreciate (land doesn’t). In 2020 Labour restored this depreciation provision, and was supported in doing so by their own Tax Working Group. And now both Labour and National are campaigning on getting rid of it again, with no more rationale than that they need revenue (and no doubt tax depreciation provisions won’t show up in the focus groups). The intellectual bankruptcy behind this is evident in National’s document

No rationale at all beyond claiming it was a “tax break”. They rightly pushed back when Labour called interest-deductibility a tax break – it wasn’t, business operating expenses are generally deductible – and depreciation is no different. (Arguably, simply calling it a tax break is no worse than Labour pretending the 2020 change as a temporary Covid stimulus measure when they were quite clear at the time it was permanent, but…..it is a close call. Our political parties………)

Finally just a fairly small technical point. Willis claimed this morning that the National package would not add to inflation pressures. The justification for this claim is that the package is fiscally neutral. That isn’t necessarily sufficient for there to be no net demand impact. For example, the tax cuts etc are skewed towards people who probably have a very high marginal propensity to consume, and the revenue sources probably less so. Perhaps more important, and as someone pointed out over lunch, 20 per cent of the revenue is coming from the foreign buyers tax. Since the higher end, most lucrative, foreign buyers – some billionaire wanting a luxury mansion – mostly won’t be paying the tax out of New Zealand income that additional tax revenue may not represent any diminution of demand in New Zealand. These are small points – the whole (funded) package is less than 1 per cent of GDP – but all else equal I would expect it to be slightly stimulatory. Those compiling Treasury’s fiscal impulse measure might think the same.

The IMF probably wouldn’t think it was a step in the right direction. Perhaps the same will be able to be said for Labour’s plans as they unfold?

UPDATE: On the fiscal impulse issue, the removal of the regional petrol tax in Auckland has the potential to be net stimulatory, at least for a time, as the Auckland local authorities had to wind down projects or identify alternative revenue sources. Re the foreign buyers tax, there may be an incidence question (purchasers of mansions may be able to push the tax incidence back onto vendors, but probably not purchasers of $2.1 million houses in Roseneath or Epsom (where there would normally be more potential domestic purchasers)). In any case, I think most estimates of spending from capital gains – by fairly well-off vendors- probably assume a lower MPC than spending from income.