There is a full Monetary Policy Statement from the Reserve Bank and its Monetary Policy Committee tomorrow. No one expects them to do anything much, but I’m less interested in what they will do than in what they should do. It is hard to be optimistic that the Committee will do the right thing at first opportunity – it mostly hasn’t for the last 3.5 years – but whatever is required will, presumably, eventually get done, perhaps after a prolonged dalliance with the alternative approach (if you think that cryptic, think $10-11bn of LSAP losses, entirely the responsibility of the MPC, and core inflation persistently some multiple of the target that had been set for them).

I wrote a post a couple of weeks ago looking at what had been happening to monetary policy and inflation across a bunch of advanced economies in the light of the complete suite of June inflation data. I’m not going to repeat all the analysis and discussion from there, and nothing very much has changed in the published data (for real nerds, still disconcertingly high Norwegian core inflation has come back down again after rising the previous month or two). But some key relevant points were:

- as yet, there is no sign that core inflation in New Zealand is falling (and even if one measure it might be lower than the early 2022 peak there is no sign it is still falling now). That is a quite different picture from some other advanced countries (notably the US and Canada, but also Australia).

- employment appeared to continue to be growing strongly (and even confidence measures were stabilising),

- New Zealand is one of a small handful of advanced countries where the policy rate now (5.5 per cent) is still well below the pre-2008 peak (8.25 per cent)

- The MPC asserted at their last review that they were “confident” that they had done enough. Neither those words, nor the idea, appear in the recent statements of any other central banks, and our MPC offered no reasons for their confidence.

Bear in mind that with core inflation around 6 per cent and the Bank’s target requiring them to focus on the 2 per cent target midpoint, there is a very long way to go. It isn’t a matter of getting core inflation down by 0.5 or 1 per cent, but of a four percentage point drop.

Bear in mind too that whereas past New Zealand tightening cycles have typically seen total interest rates rises similar to what we’ve seen to date (a) the scale of the required reduction in core inflation is greater than anything we’ve needed to achieve for 30+ year, and b) unlike typical New Zealand tightening cycles there has been no support from a higher exchange rate.

What local data there have been in the last couple of weeks hasn’t given us any more reason for comfort. Late last week, there were the monthly rentals and food price data. The food price data did look genuinely encouraging, although it was a single month’s data in a part of the CPI that had seen inflation far faster than the core measures until now. Rents, on the other hand, appeared to be continuing to rise quite strongly, with no sign of a (seasonally adjusted) slowing at all.

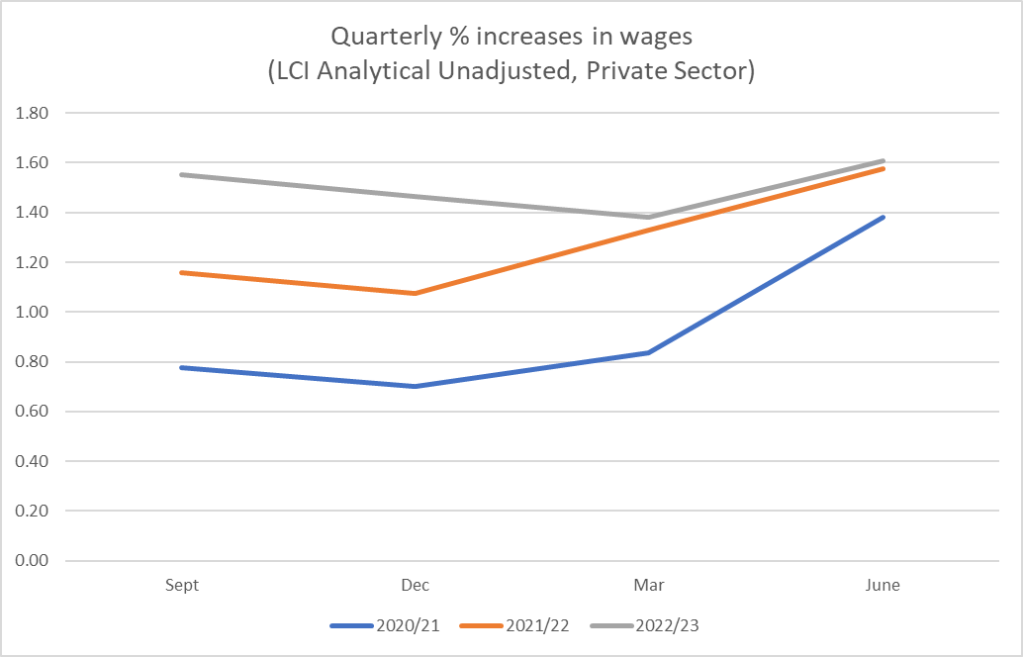

The suite of labour market data (HLFS, QES, LCI) was not really any more encouraging. Labour market data do tend to be lagging indicators, but we have to use what we have. 4 per cent annual growth in numbers employed (comprised of four individual quarters each showing material growth) is absolutely and historically strong, by standards of past cycles the unemployment rate has barely lifted off the (extremely low) floor, and there is no sign of any slowing in wage inflation (remember that much of services inflation is, in effect, wage inflation). There is seasonality in the wages data and SNZ don’t publish seasonally adjusted series but as this chart illustrates at best wage inflation might be levelling out, not much higher than the same quarter in the previous year.

To the extent the mortgage borrowers/refinancers tend to go for the lowest shortish-term fixed rate on offer, current two year fixed rates are barely higher than they were at the end of last year, and all the reports from the property market suggest a bottom has already been found and prices are already rising (still modestly) again.

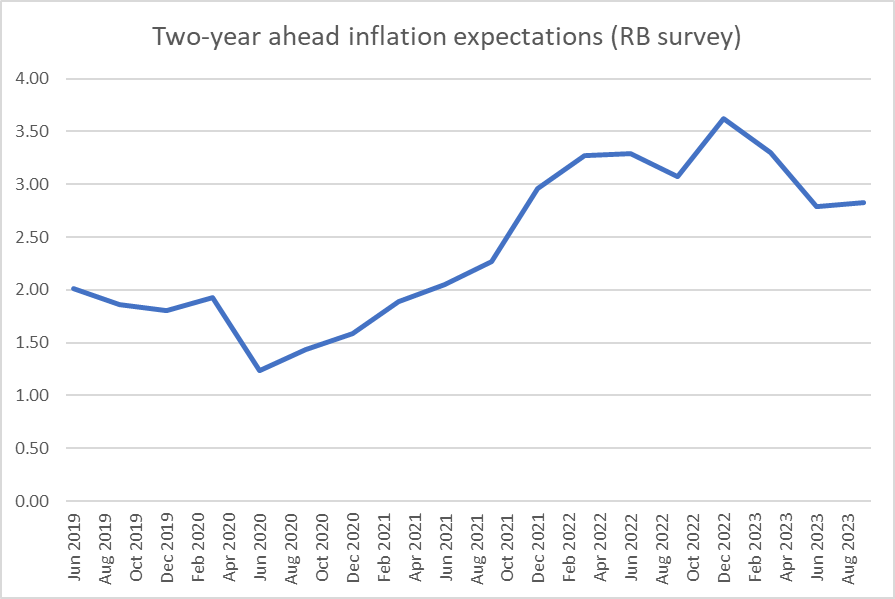

And then there was the latest RB survey of expectations. Medium-term expectations of inflation actually rose a touch (one could discount the small rise, but we should have been hoping for a fall, especially as the relevant horizon date moves out each quarter). This group of respondents has consistently and badly underestimated inflation in recent years. The Reserve Bank has too, but it has done even worse than these survey respondents.

The survey responses regarding the inflation outlook don’t seem anomalous. The same respondents revised up their GDP growth forecasts, revised up their wage forecasts, revised up their house price inflation expectations, and revised down their medium-term unemployment expectations. They might be wrong – and often are – but are there good grounds for thinking the Reserve Bank is any better at present (in a period when no one really has a compelling model of what has happened with inflation – if they had, they’d have forecast it better).

You may have noticed that a couple of local banks think the Reserve Bank will raise the OCR later in the year (presumably a view that the Bank will eventually be mugged by reality). One presumes this predictions are best seen as a view that “more will need to be done”, rather than a specific confident prediction of 25 basis points being specifically what is needed. No one can be that confident (with 25 basis points). It may be that the MPC has already done enough (as they thought) or that it needs to do quite a bit more, but even in hindsight it will be very difficult to distinguish between the effects of a 5.5 vs 5.75% peak choice.

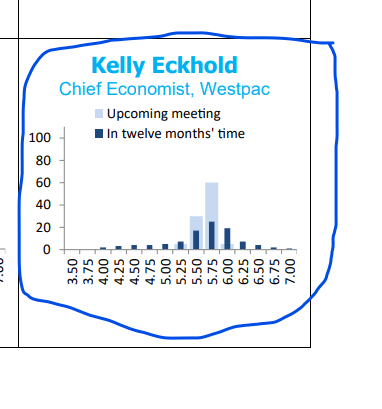

In the NZIER Shadow Board exercise, where respondents are asked what they think should be done, Westpac’s Kelly Eckhold thought that an increase in the OCR to 5.75 per cent at tomorrow’s MPS would be warranted (as does one other economist in the survey).

When I tweeted yesterday about the Shadow Board results yesterday I was still hedging my own position. I noted that I thought a least regrets approach – remember the MPC’s enthusiasm for such a model on the downside – suggested that it would have been better if the OCR had been raised more already.

That was deliberately an answer to a slightly different question than what I would do tomorrow if I were suddenly in their shoes, or (separate question again) what I think they should do. The actual MPC is somewhat boxed in by its own past choices (not just the “confident” rhetoric, but the absence of any speeches etc giving any hint of how they, individually or collectively, have seen the swathe of data that has come out since they last reviewed the OCR). To move the OCR tomorrow would bring a deluge of criticism on their heads, from markets and economists, but it would then be amplified greatly by politicians as we descend into the depressingly populist election campaign.

Since I think making the right policy adjustment (even amid all the uncertainty) is more important than communications, and since there is already reason to think the MPC has been playing party political games (its treatment of the Budget in the last MPS), I think they should raise the OCR anyway, by 25 basis points, and shift their forward-looking approach back to a totally data-dependent model, rather than trying to offer reassurances. Were I suddenly in their shoes, shaped to some extent by past choices, I would probably be wanting to indicate concern that core inflation was not yet falling, emphasising how far there was to go, and making clear that the real possibility of OCR increases would be on the table for both the October and November reviews (the latter the last before the MPC moves into its very long summer holiday).

To me, the issue now is not whether core inflation is going to fall. It seems most likely that it will finally begin to (and although overseas experience in by no means general, perhaps the US, Canadian, and Australia recent experiences offer grounds for hope) but rather how far and how slow the reduction will be. We need large reductions in core inflation, not just the beginnings of a decline, and two years into the tightening cycle we need to see large reductions soon. Perhaps it will happen with what has been done already, but that seems more like a hopeful punt than a secure outlook. One thing we should be looking for tomorrow, especially if the MPC does nothing, is some serious analysis illustrating their thinking as to why it is that core inflation here has not yet fallen (whereas, for example, it has in the US, Canada, and Australia). I don’t know the answer myself, but with all the resource at their disposal we should expect the MPC to make a good fist of a compelling story.

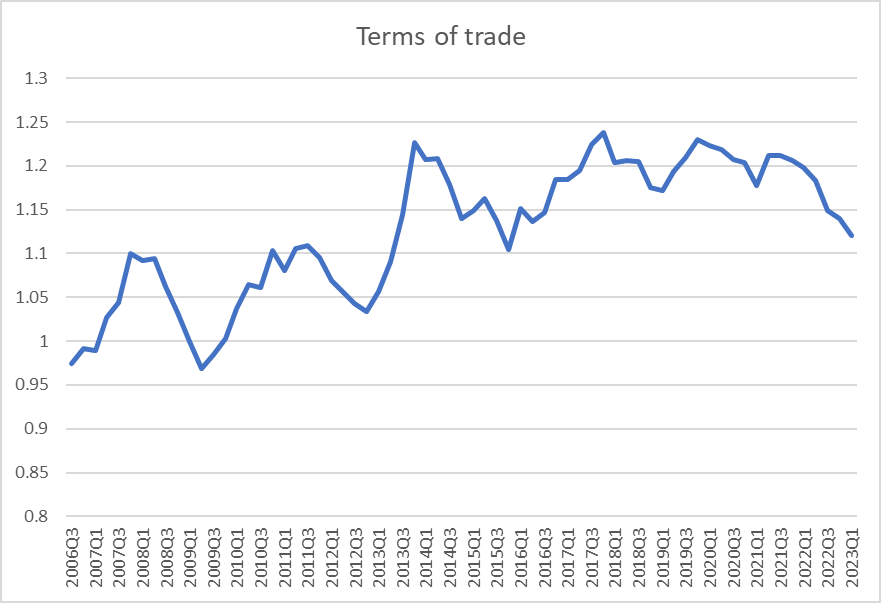

The world economy, and the travails of China, have got some attention recently. That global uncertainty will no doubt be cited by some, including around the MPC table, as reason for waiting. I’m not convinced, partly because over the decades I’ve seen too many occasions when such potential global slowdowns have been cited as an argument, only for them to come to not much. Relatedly, over the years one of the most important ways global events affect New Zealand has been through the terms of trade. A serious global slowdown might be expected to dampen the terms of trade (and thus real incomes and demand relative to the volume of domestic output) but…..

….New Zealand’s terms of trade have been trending down since Covid began, and quite sharply so since the start of last year. We’ve been grappling with an adverse terms of trade shock and have still had persistently high core inflation (and super-tight labour markets etc). There isn’t any obvious reason why the terms of trade couldn’t fall another 10 per cent (dairy prices have already weakened further in recent months, this chart only being to March), but if so it won’t be against a backdrop of recent surges of optimism (unlike the reversal in the recession in 2008/09). In short, there is plenty of time to react to really bad world events if and when they actually happen.

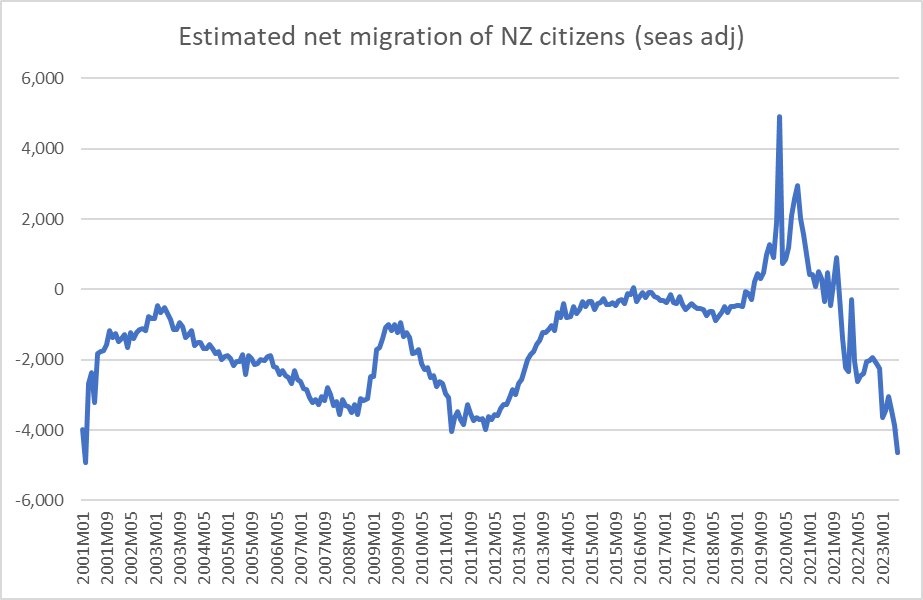

Finally, the immigration situation has materially changed the New Zealand macro position in the last year. In the June quarter last year, there was a net migration outflow of 2600 people. In the June quarter this year (June month data out only yesterday), the estimated net inflow was 20000 people (consistent with an annual rate of 80000 or so). The Reserve Bank is on record as saying it doesn’t know whether the short-term demand or supply effects are stronger (which is quite an admission from the cyclical macro managers) but all New Zealand history is pretty clear that – whatever the longer-term effects might be – in the short term demand effects, particularly from shocks to migration, outweigh supply effects. Without that effect, it might have been safe to assume enough had been done with monetary policy months ago. But not now, not against the backdrop of high and not falling wage and price inflation, strong employment growth, recovering housing market and so on.

Note too that the net inflow numbers are held down by the high and rising number of New Zealanders leaving. Outward migration of New Zealanders tends to be particularly strong when the Australian labour market is very tight (see 2011 and 2012), and if that market were to ease – as seems to be generally expected and thought to be required – the overall net inflow to New Zealand could surge again

Bottom line: I think the MPC should raise the OCR tomorrow, and certainly should flag October (once the Q2 GDP numbers are in) as live.

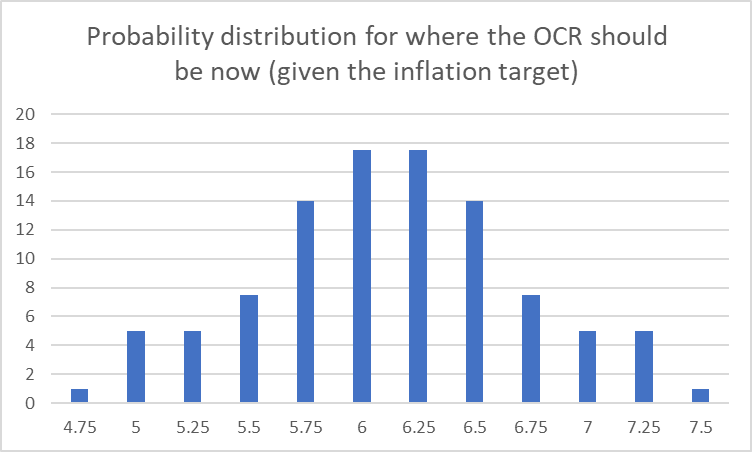

But all these views have to be held somewhat lightly. Doing that Shadow Board exercise (see above) myself, and it is something the Governor’s advisers at the RB used to have to do, I might distribute my probabilities as to what OCR is appropriate now something like this (none of those individual probabilities is higher than 20 per cent)

UPDATE:

In the comments Bryce Wilkinson points us to this. Having been in the weeds in 2007 I’m not convinced that on the information we had at the time an OCR of 10% was needed in Dec 2007. That said, an OCR of 4.3% in February 2022 would have been much better than policy as actually delivered. And note that an 8% OCR now would be close to the 2007/08 actual peak (as many other countries’ policy rates now are). Food for thought.

Absolutely agree that a hike tomorrow would be the right response (to 6pc) , but wouldn’t bet against the conservatives saying “wait and see”in a politically charged atmosphere. In our complex and relatively open economy with persistent core inflation and a “spend like there’s no tomorrow – but not on anything for growth” Government, a strong signal is needed to discourage expansionary spending and price growth. Short term linkages between rates and unemployment are uncertain and may be counter intuitive, as Scott Sumner points out https://www.econlib.org/ricardo-reis-on-the-phillips-curve/ but the core inflation is an indicator that stands out for NZ.

LikeLike

Great post. The data seems clear.

It seems obvious that the economy has fallen off the cliff, while inflation remains elevated, so we have stagflation. This stagflation is driven by a wage and price spiral, which may be exacerbated by the New Zealand currency falling. Stagflation requires a reserve bank to act independently, especially when an election is imminent.

Who is “confident” that our reserve bank is independent from political considerations?

Ha.

LikeLike

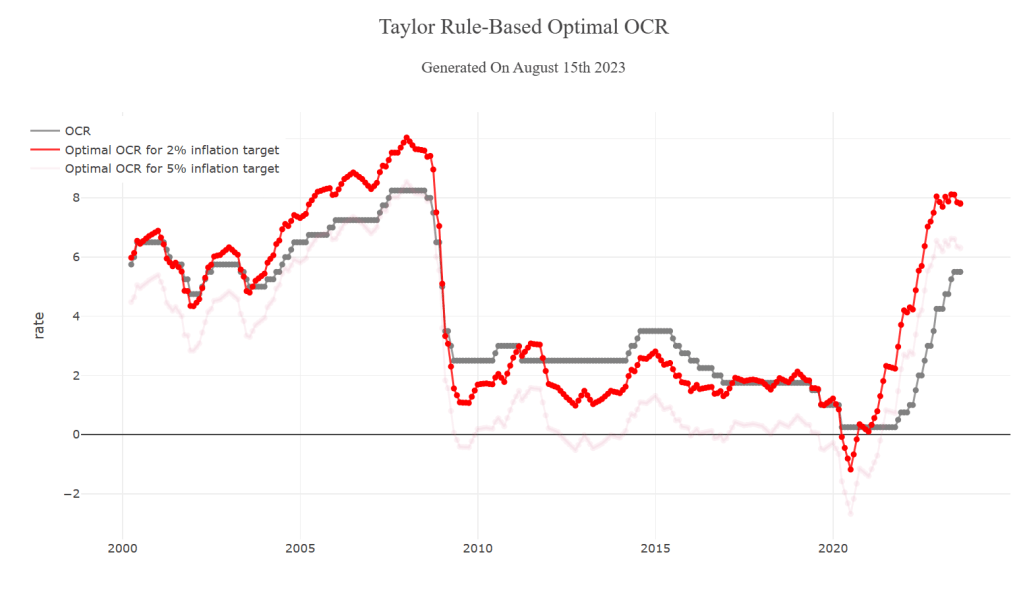

GDP live has a data-driven ‘Taylor Rule” OCR of 7.8%

https://www.gdplive.net/Dashboard#partners

Obviously, it is there to inform debate, not to predict what decision a government or MPC will take.

LikeLike

Thanks Bryce. I have put their chart of the Taylor rule recommendation on Twitter

LikeLike

Would the RB do the right thing if it wasn’t for the high mortgage level mainly caused by urban containment policies. NZ houses would be about one third of the current prices if it wasn’t for restrictive zoning – especially in Auckland. So to make the anti-sprawl zealots happy we have to have to have high inflation for longer… to add to the misery of higher house prices and rents.

LikeLike

I doubt that is much of the story. Much more important is that no one (and no cen bank) has a very good model for inflation in recent years, and it is a bit surprising (to say the least) that we have not yet seen more evidence of core inflation fallling (similarly it is a bit of puzzle why it seems to have fallen as it has already in US/Can/Aus. Reall question for tomorrow, at least for me, is how much intellectual curiousity and analytical grunt they display in thinking thru these things in a NZ context.

LikeLike

Thanks again ,including commenters , for the obvious and sensible suggestions re the OCR levels.

The RB will not move this time simply because it is election year.

Forgive the cynicism ,but it is clear that this Government is driving increased inflation as they struggle to buy back power.

The reasons for an OCR increase are clear, but the politically appointed RB have other reasons!

I think it was Milton Friedman who said that inflation was a tax.

He was right and this Government does love tax!

LikeLike

It would be interesting to see the inflation rate graphed with the Taylor rule. Bryce Wilkinson makes the comment that it could be used to inform debate. Perhaps it should replace the existing MPC! I don’t know the background of it, but perhaps there could also be an argument for the MPC explaining why they agree/disagree with the the Taylor rule on an ongoing basis

LikeLike

The main problem with the Taylor rule is that it relies on having a reasonably firm view on the neutral interest rate and the size of the current output gap. If one had a secure view then using it to pose questions re actual central bank choices would make sense (Taylor himself has suggested that approach). At present in NZ I could prob mount a reasonable case for the neutral rate being anywhere from about 2.25%to 5% (the latter roughly what the bond market is implying)

LikeLike