I watched the Q&A interview yesterday with the Leader of the Opposition Chris Luxon. Monetary policy and the position of the Reserve Bank Governor came up.

It is really quite disappointing that the Minister of Finance, presumably with the acquiescence of the Prime Minister, has so politicised the situation that a Leader of the Opposition can reasonably be asked what he would expect (eg possible resignation) of the Reserve Bank Governor after the election if National wins. If he is at all serious about his answer – appoint an independent reviewer as soon as they take office and only decide after that – it is a recipe for considerable, unwelcome, market uncertainty, and further reputational risk for New Zealand and its system of economic governance.

We really should have appointees to such positions that both sides of politics can respect and trust. That has always been implicit in the model under which the central bank is given operational autonomy over monetary policy (and the massive cyclical influence that involves), the Governor (and MPC members) are appointed for terms not coinciding with, and longer than, parliamentary terms, and (in NZ since 1990) where the Minister of Finance cannot simply appoint his or her own person as Governor. That expectation was further reinforced when the current Prime Minister and Minister of Finance in 2018 amended the Reserve Bank Act to explicitly require consultation with other parties in Parliament before a person is (re)appointed as Governor.

When Adrian Orr was first appointed at the end of 2017 that “general acceptance” threshold was probably met. There was plenty of Orr sceptics about. although often rather quietly (since they or their employers had to deal with either NZSF or the Reserve Bank, and Orr was never known for embracing criticism), but there was no great controversy about the appointment (as it happened the search and selection process had been well underway before the election and change of government, and the Bank’s Board – which put forward Orr’s nomination – had been entirely appointed by the previous National government).

It isn’t the case now. The two main Opposition parties had both made clear to the government, when the legally-required consultation occurred, that they had concerns about the proposed reappointment. But there has been no hint or sign that the Minister of Finance made any effort to engage to allay those concerns, instead – his own legislation notwithstanding – he simply pushed ahead and reappointed Orr, having had the nomination made by the new Reserve Bank Board, possessed of almost no subject expertise, he himself had appointed just a couple of months earlier. Perhaps a bit like the entrenchment outrage in the headlines today, it was lawful (much is in New Zealand) but it was far from proper.

(As I’ve pointed out before the actual argument National made in their letter re Orr was weak and their historical parallel was flawed, but then they were caught in a difficult position – unless Robertson heeded their concerns and looked elsewhere for a new Governor, they could be stuck with Orr as Governor, almost certainly unable to dismiss him (unless he did something particularly new and egregious in his new term) – and may have felt reluctant to outline a range of specific concerns about Orr and his stewardship in writing.)

TVNZ’s interviewer, who usually does a fairly good job, seemed to come to yesterday’s interview holding a brief for Orr. Among the lines he put to Luxon was the suggestion that he shouldn’t be too critical or Orr and the Bank because they had been the first developed country to raise their policy interest rate. This is the sort of spin the Bank itself likes to hear, and it uses a more-muted version of it at times. I don’t know how many times it has to be said but it is simply a false claim. It isn’t a matter of interpretation or nuance, it is simply false.

There are probably two main sets of groupings that are used to capture a list of developed countries or advanced economies. The first is membership of the OECD, and the second is the IMF’s “advanced economies” groupings. Neither is ideal. The OECD includes several Latin American countries (Costa Rica, Colombia, Chile, and Mexico) that are mostly much poorer and less productive than other members (I’ve often suggested they are “diversity hires”),and excludes Singapore and Taiwan. The IMF list on the other hand does not include any of the Latin American countries, but in central and eastern Europe seems to include countries if they are in the euro but not if not, even if the latter are equally productive. Since so many advanced countries are in the euro, there are really only 20 or so countries with monetary autonomy, setting their own interest rate.

On several occasions in the past on Twitter I’ve used the BIS’s monthly data on policy interest rates. Of the countries there that are on either the OECD or IMF lists, these were the first countries to raise policy interest rates in 2021.

Discount Mexico and Chile if you like and you are still left with five advanced country central banks having moved before our Reserve Bank did, all of them for countries that are either materially richer/more productive than New Zealand or (Korea, Hungary, Czech Republic) about the same. You could make further allowance for the Reserve Bank and accept that if their MPC meeting in August 2021 had been a day earlier, the OCR would first have been raised then, but they still wouldn’t have been the first to move.

There is no question but that our Reserve Bank moved earlier than the other Anglo central banks (or even the ECB) but what of it?

More generally, when individual central banks moved (early or late in calendar time) is really neither here nor there anyway. Each central bank faced different domestic situations in terms of capacity pressures, emergent inflation, and the core inflation outlook.

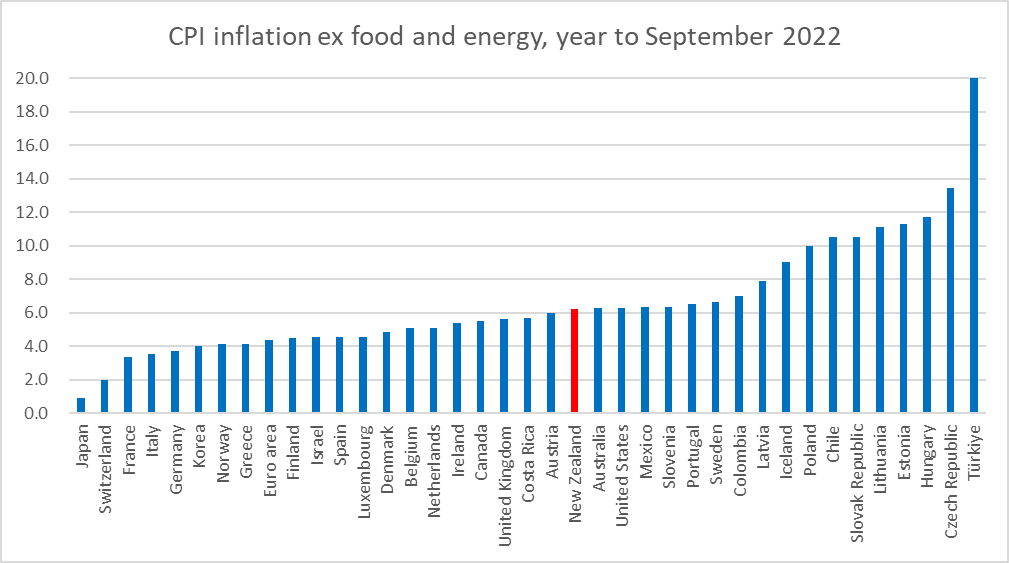

I’m not going to attempt to analyse the story each central bank faced last year, but I’ve shown this chart in a previous post.

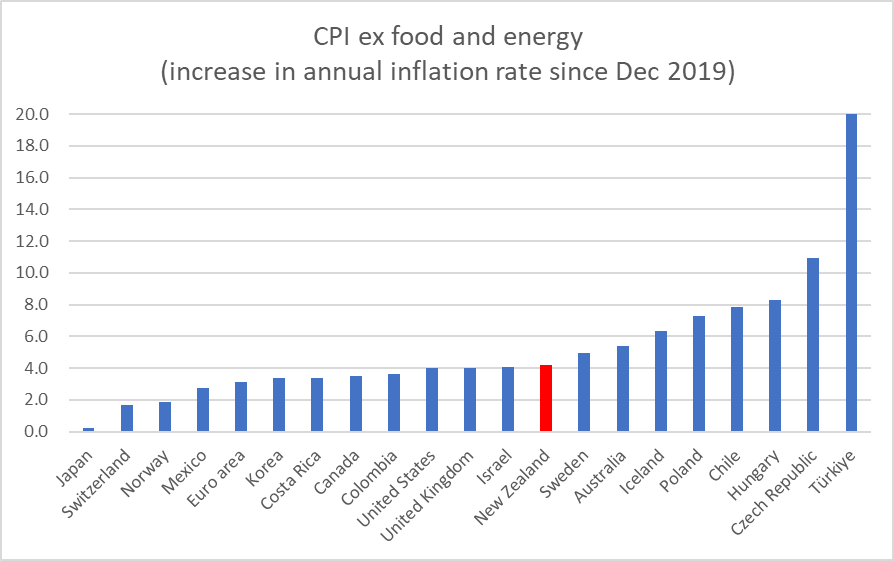

On the most recent data, for the only internationally comparable measure of core inflation we readily have, New Zealand’s core inflation rate now – a year on from the first OCR increase – is nothing special, being just above that of the median OECD country. If we focus only on OECD countries with their own monetary policies (and the euro area as a single observation) we get this chart showing the increase in the core inflation rate since just prior to Covid (actual Turkey increase is far larger than the scale allows).

It isn’t one of the worst, but again it is slightly worse than the median country (and, as it happens, worse than in three of the four Anglo countries, and worse than the euro area).

This isn’t another post trying to evaluate in any detail the Bank’s absolute or relative performance, but as a general observation almost all central banks have done poorly in the last couple of years, and little about the Reserve Bank’s policies or policy outcomes stands out from the pack. Media defenders of the Governor should take note, and/or get better basic researchers.

What the post is mainly about is central bank appointments. We’ve had some dreadful ones this year – the deputy chief executive responsible for matters macroeconomic who has no background or evident expertise in the subject, and who yet is a full voting MPC member, and (see above) the reappointment of the Governor. Then there was the decision (apparently joint between the Governor, Minister and (old) Board) to keep in place the blackball prohibiting anyone with current in-depth expertise in matters macroeconomic or monetary from serving on the MPC, all as prelude to the reappointment without much scrutiny of two external MPC members whose terms were expiring.

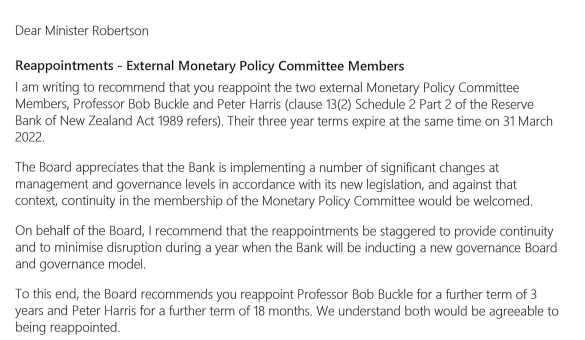

On which note, I had another OIA request back the other day, which included the letter from the Reserve Bank Board chair to the Minister of Finance recommending those reappointments. It was perhaps even more lame than I had expected. There was no attempt to evaluate or describe the contributions Buckle and Harris had made, nothing at all about the rapidly rising (core) inflation backdrop for which they shared responsibility, no suggestion of having considered any alternative candidates (neither Buckle nor Harris are young). In fact, the strongest (only) argument for reappointment seems to have been that “the Bank is implementing a number of significant changes in governance in accordance with its new legislation”, even though almost none of the 2021 Act had anything to do with monetary policy or the MPC

That letter did, however, partly answer one question I’d had. Peter Harris – former politically-appointed adviser in Michael Cullen’s office – was reappointed for a term of only 18 months to expire on 1 October 2023, right in the middle of the likely election campaign. Why, I wondered, would Robertson have done that – ministers after all being well aware of the convention that new appointments should not be made to positions starting close to likely election dates? But it turns out it was the Board’s doing, and there is no sign they gave any thought to the fact that the end of Harris’s term was going to land in the midst of the election period. Which seems quite unnecessarily careless of them. One hopes there is no question of any new appointment being made until after the election. If National were to win, the vacancy would give them an opportunity to begin to exert some influence; one would hope they would remove the bar on expertise, and at the same time amend the MPC’s charter to make it clearer that individual members were expected to bring expertise to bear and to be individually accountable.

But the current government is quite free to make the next MPC appointment. The worst of the first batch of external MPC members was Caroline Saunders. Her term expires on 31 March 2023. The papers released at the time of those 2019 appointments make it pretty clear that she was a diversity hire. Professor Saunders may be very capable in her own field but she has no background at all in macroeconomics or monetary policy. Consistent with that, we have heard not a word from here in her (almost) four years on the MPC. She has taken the taxpayers’ dime and there is no evidence she has made any contribution at all, and has done or said nothing – no speech, no interview, no parliamentary committee appearance – to provide any basis for holding her to account, even as she shares formal responsibility for the biggest monetary policy stuff-up in decades

It would be quite unfortunate if Saunders is reappointed (but most probably it is already a fait accompli, given that no vacancies have been advertised). If there was ever a case for a token female appointment (which there wasn’t; token appointees are never desirable), the ultimate in token appointees now holds a senior executive role on the committee. More generally, in any body – public or private – fresh blood should be introduced from time to time, and yet none of the externals has been changed, and (by the rules they themselves signed up to) those members are not allowed to foster any independent subject expertise themselves in their time on the MPC (and the Bank has been doing very little serious research, so there won’t be much expertise being fostered/extended inside). From a narrowly political perspective, one might have thought it might have been in the government’s interest to have found a strong new appointee who might have a good chance of doing two future terms.

Which bring us back to Luxon. It isn’t clear that National cares very much about any of this,or will fllow through if and when it takes office (why rock the boat when you now have an office to hold and savour?). I’m not at all optimistic, but if they are more serious than they seem, here was a post outlining some of things they could look at.

Reblogged this on Utopia, you are standing in it!.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I look forward to your comments about Peter Harris’s comments.

https://www.rbnz.govt.nz/hub/news/2022/11/mpc-external-committee-member-peter-harris-media-response

LikeLike

See today’s post. It is a bit hard to believe that they are quite that bad.

LikeLike