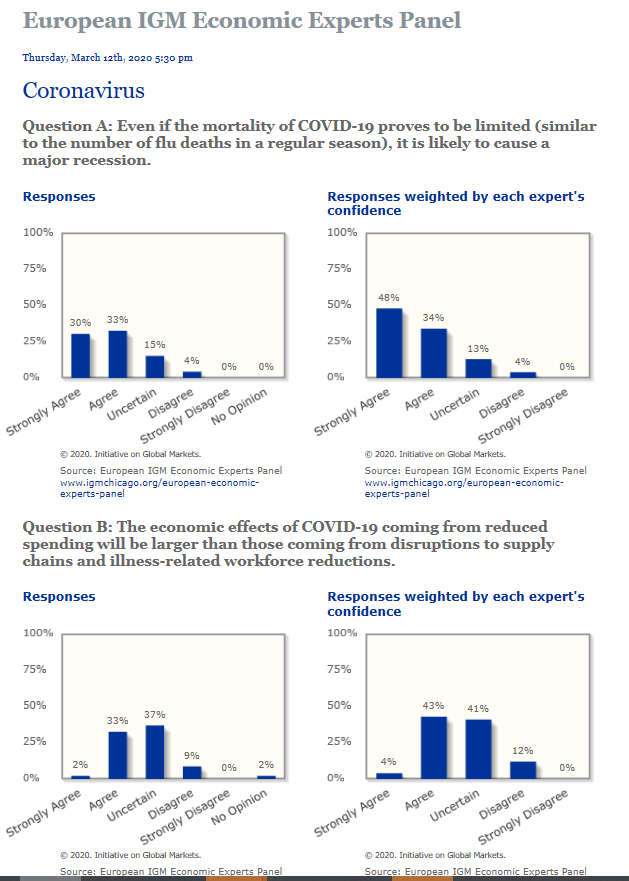

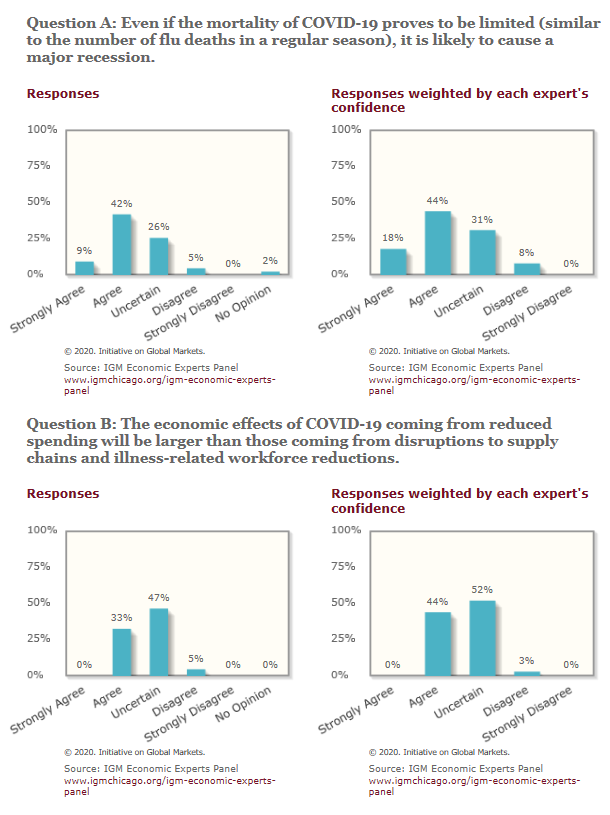

The government’s sudden decision on Saturday to substantially close the border seems to have jolted some towards realising just how serious the coming economic dislocation is. But it has also led to a plethora of comments suggesting that the “border closure” is itself the cause of, or trigger for, the dislocation and huge loss of income and output that is coming. It wasn’t. As is well known, willingness to travel internationally was drying up anyway, and was only likely to drop further, amid the progress of the virus and the skyrocketing levels of fear and uncertainty. Only the marginal additional effect of the border closure, over and above what was already happening any way, is really relevant to assessing the cost of that particular policy.

Personally, I’m still a bit sceptical about border closures now, which seem more akin to political theatre than to serious policy (with hindsight the one – simply impossible to conceive – border closure that would have made sense would have been for China to have closed its border, in and out, in November). But unless they distract attention, including media coverage and analysis, from the real and bigger issues I guess at this point they don’t do much harm either.

On the other hand, there has still been a real reluctance to grasp just how deep and long that economic shutdown/dislocation seems likely to be. There was the absurdist extreme this morning of the (overwhelmed?) Reserve Bank Governor who was reluctant to even concede a recession. But if the Prime Minister – who is usually hopeless on matters economic, including in her Q&A interview yesterday – and the Minister of Finance have been less bad than that, they’ve still refused to level with the public, in ways that leave one wondering whether even they have yet grasped what we’ve found ourselves in so quickly.

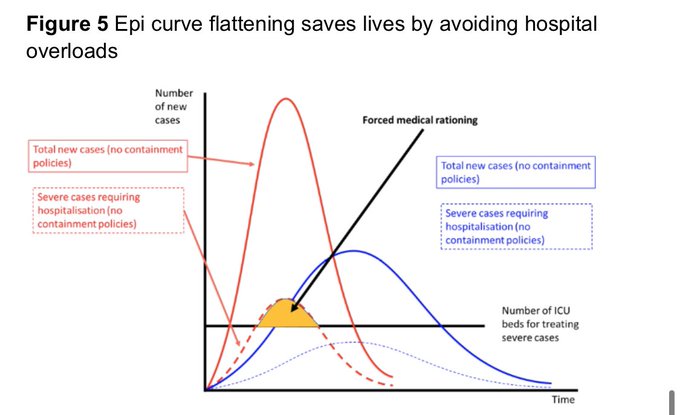

Thus, it was good on Saturday to hear the Prime Minister articulate the “flatten the curve” strategy, but neither she nor any other public figure I’ve seen or heard from has been willing to recognise that if we do flatten the curve a lot, whether by border closures or (more probably) physical distancing, there is no quick or easy exit strategy: in some form or another, perhaps varying through time, the restrictions and behavioural changes (compulsory or voluntary) have to be in place for a long time, unless/until (say) a widespread vaccine is available. That means a huge economic cost, and huge economic uncertainty, for the (uncertain horizon) future. Perhaps it is the only sensible strategy now – notice the pushbacks against the UK “herd immunity”/cocoon the elderly notions – but how does it feel three months hence? Six months? Nine months? There has been no open discussion of the exit strategy, or the implications economic and social.

It is pretty easy to develop scenarios in which real GDP for the next year could be 25 per cent lower than otherwise. Foreign tourism has evaporated. There’s 5.5 per cent of GDP gone. Perhaps a few more people will holiday locally, but more likely reluctance to travel will keep on diminishing, even if we never quite get to the point of being penned in our homes, even just outside working hours. No new investment project will start, and many of those underway will be halted – whether because of uncertainty, illness, lack of finance, disrupted supply chains or whatever. Housing turnover will dry up. On the expenditure GDP side, investment is about 20 per cent of GDP. Demand for many of our other exports will also weaken – as most every other country battens down and experiences big income losses as well as disrupted distribution channels. Personally, I went to a movie yesterday afternoon, but I doubt I’ll be going to any more for the duration. Restaurant bookings in other countries are plummeting and so on. Lock people down Wuhan style – or have them so fearful they won’t venture out – and of course for a time the losses are even greater.

It is an enormous loss of income and wealth, most of which will never be recouped. Those losses will be borne – the only question is who bears them. That is likely to be some mix of law, canons of fairness/justice, and considerations of economics (what will help us eventually emerge with the least semi-permanent damage).

A key aspect of my approach to this issue is that now is not the time to be encouraging more spending and economic activity. In fact, to do so is likely to run directly counter to the public health imperatives. There will come a time when we do want people to emerge from their shells and be ready, eager, and able to spend. But not only is that time not now, but a realistic take on what “flatten the curve” seems to mean here and abroad, suggests that at best that time will not not be for many months yet.

So talk of stimulus packages is really quite misplaced (much of the Australian package last week will have really just be wasted money). The focus now needs to be on three things in my view:

- basic income support for everyone, whether through companies or through the welfare system,

- throwing all that can usefully be thrown at gearing up health system capability (I have no idea what can actually be done, but the impression so far is that not much has been done, perhaps so as not to muddy the waters of the political message about our “world-class health system”, when it is clear that no health system in the world can cope with very much of this virus at once – another message politicians have not fronted the public with), and

- creating a climate of confidence that in time – as soon as possible, but it won’t be soon – things will get back to normal, including economically, and that the authorities will not stint in helping that happen WHEN THE TIME COMES, which is not now, and cannot be now. Included among the imperatives regarding confidence are things around medium to long term inflation expectations – something the Bank used to like to talk about, until it really mattered – and the assurances it takes to create credit and liquidity available.

So here I want to propose a strategy or framework for approaching the period ahead, the period before there really is light at the end of the coronavirus tunnel. When that light becomes evident, my suggestion of the temporary cut in the rate of GST would be apt, as would a temporary cut in one of the lower income tax bands. A one-off significant lump-sum cash transfer might even have a place. And monetary policy would have been fixed in ways that mean interest and exchange rates strongly accommodate any nascent uptick.

But in the meantime here is something along the lines of what I think needs doing.

First, people keep playing down just how much it matters that monetary policy cannot adjust very much. Even in normal recessions, whether or in the US or elsewhere, cuts in short-term interest rates of 500 basis points or more are quite normal. This economic dislocations seem almost certain to be larger than anything anyone living has ever experienced in countries with their own monetary policy. We simply cannot accept the status quo of an effective lower bound on nominal interest rates not far below zero (let alone the rank incompetence that for now has the RBNZ telling us the floor is 0.25 per cent, because they hadn’t ensured banks could cope with negative rates).

This problem can be solved. The effective lower bound arises because people- and institutions can convert deposits into cash, which yields zero, rather than accept a materially negative interest rate. It isn’t worth doing so – insurance, storage, AML laws etc – for a few tenths of percentage points, but if the OCR were to be set at – 5 per cent (quite plausibly what would be sensible now: there are papers for the US in 2008/09 which suggested -5 per cent would be appropriate then) the general consensus is that such conversion would occur on sufficiently large scale to make it not worth cutting that deeply.

But those restrictions can be eased, temporarily or permanently. If, for example, the banks had to pay a premium of 5 per cent over face value to purchase (net new) notes from the Reserve Bank, they’d be likely to pass that cost on to customers – and particularly to any large customers. If a pension fund (say, and I’m a trustee of two so have thought about these options) considered switching into physical cash and faced a 5 per cent fee, they’d have to think about how long they expected the crisis to last. If they thought it would be largely over this time next year, you’d rather accept a -5 per cent interest rate in a bank that pay the insurance and storage costs on top of the 5 per cent cash fee. It isn’t technically hard to do. It is pretty countercultural – cash and deposits have been essentially interchangeable – but then so is coronavirus and the attendant economic and social disruption. There is a bunch of other ways of achieving much the same effect. They can be done in fairly short order (and announced, for the signalling benefits) even sooner.

Doing so would help ensure we could keep driving the exchange rate down, (as the Governor put it) a standard part of the buffering mechanism in New Zealand. And it would demonstrate to markets, and anyone else paying attention, that New Zealand authorities were absolutely determined to keep medium-term inflation up – in the face, for the next year or so, of an otherwise deeply deflationary shock – which might even lift inflation expectations, but would at least limit further erosion.

This stuff is geeky and may not make much direct sense to the man in the street. But it is a reallly important part of a successful macroeconomic framework. It does not put money in pockets now, but it helps keep the climate right for an effective recovery.

And what it would do is enable us to make a much more brutal and effective start on the appropriate income redistribution to fit the crisis. Interest rates are really a reward for waiting, and for the opportunities used/foregone over periods of time. But for the economy as a whole there really is no value in time at present. And yet we still have deposit and lending rates – even after today’s cut – well above zero. That simply shouldn’t be for the time being.

Of course, there are arguments around negative rates that depositors won’t readily accept negative returns. Those are arguments – mostly about slow adjustment of norms – for relatively stable times, not for the next year or so. What else are the depositors going to do with their money? Extreme risk aversion will deter them from purchasing other assets here, and if they either shift abroad or starting spending either effect works in the macro-stabilising direction.

And on the other hand, in deep recessions servicing burdens for floating rate debt typically plummet. That seems even more imperative than usual (for a recession) now.

In other words, radically lower interest rates would (a) lower the exchange rate, (b) achieve a desirable and typical downturn redistribution from depositors to borrowers, and (c) help create the medium-term confidence in the rate of inflation once we’d emerged. Those are significant gains even if no more overall economic activity is induced right now in the midst of the crisis.

If the Reserve Bank won’t act to do this now – and they’ve shown no sign of any energy thus far, including nothing more than a passing mention in last week’s speech – the Minister of Finance should insist on it, using his existing monetary policy override powers or, if they aren’t enough, passing special legislation.

Consistent with this, the Bank should – and quite possibly will within the next couple of weeks – starting standing in the market offering to purchase any and all government securities at a yield of (for the sake of a round number) 0 per cent. Doing so would not make much difference to short-run economic outcomes – frankly little (other than the virus) will or really should – but it would be a strong signal of how committed the authorities are to avoiding a deflationary shock turned into a deflationary underemployed semi-equilibrium. It would also establish upfront that any bond market disruptions – and there may be more – would not impede the government’s ability to raise whatever it takes over the period ahead. (And for monetary tragics, yes wouldn’t Major Douglas and Bruce Beetham have marvelled to see such an hour).

The second strand of my adjustment package is a proposal for a wage cut, across the board, of (say) 20 per cent for the coming year. Remember that I noted that GDP could easily be 25 per cent lower than otherwise for the year ahead. Someone (lots of people) will bear that loss. Most owners of businesses/shares will take very heavy losses for the time being. Many people face losing their jobs, or being unable to find one (at a mundane level my son, in Year 13, fairly suggested that finding a holiday job next summer, prior to starting university is going to be…..well, challenging). They lose out very heavily (recessions never fall evenly). And at the other extreme, who won’t be losing out at all? That would be the 20 per cent of so of the workforce employed in the public sector, few or whom will face any material risk of redundancy. (And sure, some public sector workers will be working harder than ever, but so will some private sector workers – and in case anyone thinks this is beating up on public servants, our main household income is a public service salary.)

In such a dramatic climate, across the board wage rates seem fair, as a way of distributing the (inescapable) losses and pain. It would have to be done by legislation, which might not be that easy to draft, but it is one of those cases where centralised coordinating devices allow adjustments that couldn’t otherwise readily or quickly occur (the floating nominal exchange rate serves a similar function).

Now, of course the typical high income person can afford to lose 20 per cent of their wage for a year more readily than someone at the bottom. But in a typical recession the labour income losses are concentrated even more heavily on low income people, so that isn’t a particular argument against what I’m suggesting. But frankly most people are likely to be spending less anyway over the next year, even if it is just saving the bus fare if people are coming into the office less often (or not at all), or closed bars or movie theatres etc. But one could tailor the scheme to some extent: perhaps a fulltime equivalent cut of 20 per cent to wage rates, but cappped at $4000 (FTE) for low income workers?

Now one loud objection will be that such a cut will be deflationary: less income, less spending etc. But (a) I have another big strand to come, and (b) recall that this is mostly redistribution – instead of most losses falling on firms, more of them would be borne by workers (being as we are all in this together). And don’t forget that the first strand of my suite of framework policies was a radically expansionary monetary policy, relative to what we have now.

The third strand of my framework – perhaps the most controversial of all – starts from asking the question of what we’d have done 20 years ago if we’d really focused on pandemic risk, including at a macroeconomic level. Presumably the answer is that we would have sought insurance. It would not necessarily have been available on market – especially not from anyone we’d count on to be around to meet the claims – so we’d have self-insured. In fact, in the sort of as-if argument favoured by economists you could mount an argument that that is exactly what we have done, across successive governments, by keeping government debt low (and taxes higher as a result – in effect, the premium). Now is the time to draw on the policy.

I should say that much of what I’m about to suggest sticks in the craw. There are some firms that I really have no sympathy with at all: if you are an airline then after 20 years of 9/11, SARS, H5N1 planning, H1NI, MERS, and the never-long-away risk of major new terrorism, you surely have to plan on the basis that sustained disruption in ability to fly is a core business risk. But, even if politics didn’t mean any such argument would just get ignored anyway, I think we have to set such perspectives aside, in the interests of a timely restoration when the virus fades as an issue/risk.

At a conceptual level, I am going to propose something like an “ACC for the national economy”. ACC, you will, recall typically cover 80 per cent of lost earnings.

So how about committing as a country, and by law now – would be needed to have the effect I’m seeking – that for the tax year 2020/2021 – we would guarantee that everyone taxpayer’s net income would be at minimum 80 per cent of what they received in 2019/2020. That guarantee would apply to firms and individuals, even foreign-owned firms with substantial operations actually here. (For firms, it might be conditional on – and scaled to – maintaining at least 80 per cent of the 31 Dec 2019 workforce.)

I’m not here proposing a mechanism to operationalise the payouts of these guarantees, but I don’t believe that would be necessary now. It would, in effect, be akin to a government bond or guarantee which people and firms could count on and – as important – their banks could count on. With such a guarantee, there would be less reason for banks to be reluctant to keep existing loans outstanding, or indeed to extend further credit to cope with the – often significant cash flow hole. It wouldn’t avert all failures – and nor, generally, would that be desirable – but it would make a huge difference, and provide a high degree of certainty about income floors up front.

The guarantee doesn’t, of course, make people whole (not adversely financially affected) but then all this is on the assumption that 25 per cent of GDP is lost. Those losses have to be borne by someone (and, as noted above, spending opportunities are going to be fewer anyway).

Recall again that the goal isn’t, and should not be, to stimulate new spending at a time when people have to hunker down, be careful, separate etc. It is about minimising the longer-term disruption from a totally unforeseen, genuinely exogenous to the New Zealand economy shock. Done well, firm failures and job losses – at least of permanent employees – should be kept to a minimum (as will inevitably be the case in the core public sector anyway), and keeping up something like the required level of credit (much of any addition, secured by a statutory government commitment). Same applies to household mortgages.

How much would it cost? It is impossible to tell. But here’s the thing. On the OECD net general government financial liabilities series, New Zealand’s net government debt is about 0 per cent of GDP. That’s right, zero.

Suppose we lose 25 per cent of GDP for a year, but decide to pay every New Zealander (individual and firm) just what they got the previous year, what would that leave net government debt at the end of that year? Well, that would be something like 25 per cent of GDP. Not exactly high by international standards, having traversed one of the very worst shocks imaginable outside war. Of course, the lost output could be larger than 25 per cent of GDP (in Wuhan it will almost certainly have been larger than that so far), or the losses could run longer than a year. But worry about the second year when we get closer. For now, an strong demonstrated fiscal commitment should support both credit and jobs. And, as a society, we pay for it in higher taxes over the following 20 or 30 years. It is, essentially, ex post pandemic insurance.

(If you wanted you could add some sort of “windfall profits tax”, levying a higher tax rate this year on anyone whose income in 2020/21 was more than 20 per cent higher than in the previous year.)

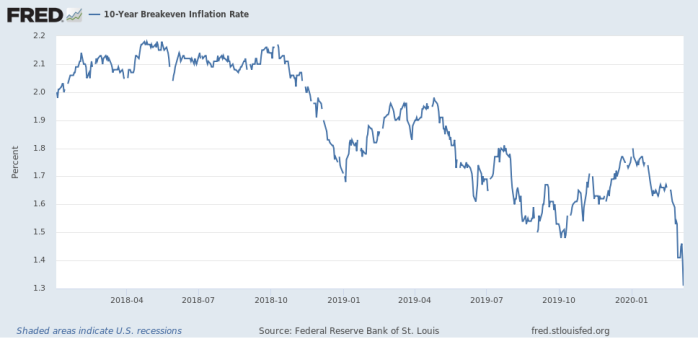

And that it is it for a big macroeconomic framework package. It doesn’t obviate lots of short-term issues, including perhaps around sick leave etc. It doesn’t render irrelevant series stimulus effects – fiscal and monetary – to demand and activity as the virus looks to be sustainably behind us. What it is designed to do is (a) share the inescapable) losses fairly, if inevitably a bit crudely, without removing all risk from individuals or firms (b) support the existing level of credit and a secure basis on which existing banks could lend to cover shortfalls, (d) dramatically cut servicing burdens (and returns to depositors) as is normal in a deep recession ,and e) support/create confidence in an absolute commitment to keep medium-term inflation up at around 2 per cent, avoiding seeing real interest rates rising into a savagely. deep and at least somewhat prolonged recession and deflationary shock.

I’m sure there are many detailed pitfalls and issues to address. Perhaps the biggest high level one is the possibility this is all over three or six months hence. Frankly, I don’t even think that is really worth considering very seriously at present, but even if it were to happen (a) the wage cut could be shortened (new legislation) and (b) the net income guarantee is just that: if it isn’t called because incomes recover very quickly, then that is just great for firms, households, individual and governments.

I commend it to your consideration.