On Tuesday afternoon we learned that the Minister of Finance had written to the Governor of the Reserve Bank about housing and monetary policy. At his press conference yesterday, the Governor told us that the first thing he knew about it was on Monday, suggesting that the government had become worried over the weekend that it was on the political backfoot on housing and felt a need to be seen to be doing something/anything, to change the headlines for a day or two at least.

There wasn’t much to the Minister’s press statement. Perhaps it might even have seemed not-unreasonable if he’d come into office for the first time just a few days ago, but he’s been Minister of Finance for three years, and the housing disaster has just got steadily worse over that time. Little or nothing useful has happened in that time to do anything other than paper over a few symptoms of the problem. And no one believes any agenda the government has is likely to markedly change things for the better: if they did, expectations would already be shaping behaviour and land/house prices would already be falling. Why would one believe it when the Prime Minister refuses to talk in terms of materially lower house prices, and even the Minister of Finance yesterday could only talk about wanting “a sustained period of moderation in house prices” – ie enough to get the story of the front pages, not to actually fix the problem? That makes them no better than their National predecessors.

And so he made a bid to play distraction, writing to the Governor and suggesting that he (the Minister) might change the Remit the Monetary Policy Committee operates under. The Minister can make such changes himself (he does not need the Bank’s consent), but must seek comment from the Bank first.

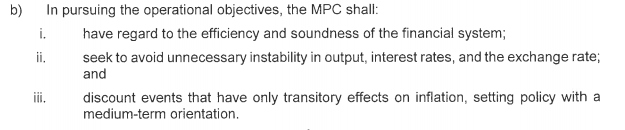

It was a limp suggestion, as the Minister must have known when he wrote the letter (and as The Treasury would almost certainly advised him, if he asked for advice from them). In the Remit, consistent with the Act, the MPC is required to use monetary policy to keep inflation near 2 per cent, and consistent with that to do what it can to support “maximum sustainable employment” (in practical terms, low unemployment). And then there is this

The Minister suggested in his letter that he might like to add “and house prices” to the end of the worthy grab-bag phrase in b(ii).

b(ii) has been in the Bank’s monetary policy mandate (the old Policy Targets Agreements – which I’d link to, but the Bank seems to have removed them from their website) since the end of 1999. It was inserted when Labour became government that year and the new Minister of Finance, Michael Cullen, wanted some product differentiation. The Bank had had a bad run over the previous parliamentary term, including the period when it ran things using a Monetary Conditions Index operating guideline, which led to us actively inducing a wildly unnecessary degree of variability in short-term interest rates. Cullen had also, for some years, been somewhat exercised about the cyclical variability of the exchange rate.

It was cleverly-crafted wording. Don Brash agreed to some new words that sounded worthy – who, after all, wants “unnecessary” variability in anything – but which really changed nothing at all. Better (or worse) still, no one has ever known quite what it meant, or if it meant anything at all beyond what was already implicit in a medium-term approach to inflation targeting (looking through short-term price fluctuations – per b(iii) now – had always been integral to the way we’d run thing). A lot of time and energy was spent trying to articulate what it might mean – the Bank’s Board were particularly exercised, since they were supposed to hold the Governor to account, and it wasn’t clear how, if it all, b(ii) changed anything. For practical purposes, in all the years I sat on the OCR Advisory Committee, with b(ii) as part of the mandate we were advising against, I’m not convinced it ever made any material difference to any specific OCR decision. If the Governor didn’t want to tighten much anyway, it was sometimes a convenient reference point – wanting to avoid “unnecessary instability” in the exchange rate – but a more hawkish Governor, or a more accurate set of forecasts, might just as easily have determined that any resulting pressure on the exchange rate, while perhaps a little regrettable, was nonetheless, “necessary”. And then there were the tensions – avoiding a bit more upward pressure on the exchange rate might actually contribute to increasing the variability in output, and so on.

The clause was, and is, largely meaningless in any substantive sense. From a purely substantive perspective I’ve argued for some years that it should simply have been dropped, but the fact that it lives on is a reminder that documents grow not necessarily because the substance requires it, but because there is a political itch to scratch.

So Grant Robertson’s suggestion that he might change the Remit to add “and house prices” to b(ii) should be seen in exactly that light. It is about scratching political itches – and distracting from the government’s own failures on housing – not about substance. We know this also because the Minister was at pains to reassure people that he wasn’t proposing to change the operational objectives the MPC is required to pursue. If not, then adding “and house prices” is really no more than getting the MPC to add another few lines to the occasional MPS, to imply that they had paid ritual obeisance. It might do no harm, but it will do no substantive good either.

But it won Robertson quite a few headlines, and even got the markets excited for a while, temporarily prompting the sort of lift in the exchange rate that might otherwise appear appear out of step with the government’s alleged desire to promote investment in more “productive assets”.

But if there was anything real to it – if the aim was actually to make the MPC set monetary policy differently (tighter at present) – it would, of course, have to have come at the cost of a more sluggish recovery, lower than target inflation, and cyclical unemployment higher than necessary. Which would have seemed very odd coming from a Minister of Finance who had explicitly introduced to the Act – what was always implicit – the cyclical unemployment dimension just a couple of years ago, complete with reminders of the importance his Labour forebears – notably Peter Fraser – had placed on full employment. (I suppose, charitably, it could have involved some more fiscal stimulus to offset less monetary stimulus, but if the Minister had been serious about that he could do it anyway – the RB sets monetary policy in the light of government fiscal choices whatever they are.)

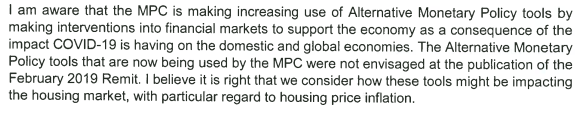

But of course it wasn’t serious. It was political theatre, and distraction, including an attempt to distance himself from monetary policy policy that he had explicitly authorised. Thus he claims

But as the Minister knows very well, not only was the Bank well advanced in thinking about unconventional monetary policy options by then – they’d published a whole Bulletin article about it in May 2018 – and much of the rest of the world had been using them for some years, but that the LSAP programme (the one actually in effect this year) has been inauguarated with the explicit and repeated consent of the Minister of Finance himself (through the guarantees he has provided to the Bank). Unconventional monetary policy is, in any case, yet another ministerial distraction, since no supposes that whatever contribution monetary policy might have made to this year’s house price developments, it would have materially different if the Minister had ensured that the Bank had its act together in ways that meant that they used a negative OCR this year.

Anyway, the Minister’s letter prompted a quick response from the Bank. Perhaps some wonder if that was necessary – these things could be dealt with to a greater extent in private – but I’m with the Governor on this one. It was the Minister who chose to issue his letter the afternoon before the Bank’s long-scheduled FSR press conference. The Bank had no effective choice but to respond, and better to put things in writing than just rely on throwaway comments at a press conference.

I thought the Governor’s letter was mostly a fairly sensible and moderate holding response. He promised to come back to the Minister with more considered thoughts on the suggested addition to b(ii). There were a couple of bits that could be read more pointedly. For example, the Governor noted that

We welcome the opportunity to contribute to your work programme aimed at improving housing affordability. As I’ve said publicly on many occasions, monetary and financial regulatory policy alone cannot address this challenge. There are many long-term, structural issues at play.

The Bank had, in fact, had some nice lines to that effect in its Monetary Policy Statement just a couple of weeks ago

This is a government failure, not a central bank one. But I guess I wouldn’t expect any central bank Governor to be quite that pointed in public.

Several have also noted that the Governor pointed out that the Bank already considers house prices in setting monetary policy.

I can assure you that the MPC, in making its decisions, gives consideration to the potential impact of monetary policy on asset prices, including house prices. These are important transmission channels that affect employment and inflation. Housing market related prices are

also included in the Consumer Price Index, for example rents, rates, construction costs, and housing transaction costs.

But actually that was a bit cheeky. On those terms, at times like these the Bank positively welcomes higher house price inflation because of the beneficial spillovers they think that leads to in raising CPI inflation. Recall just a few weeks ago their chief economist was actively welcoming higher house prices, distinctly averse to falling prices.

Out of that first round, I’d suggest that the Governor came out ahead on points. The Minister got his headlines – lots of them in some media – but the Governor gave no hint of believing that there was likely to be anything of real substance there.

But the Governor must have over-reached yesterday. At the FSR press conference he expansively declared his pleasure that the Bank has been invited to share its expertise in advising on the wider issues of supply and affordability. In an interview with Stuff – now the frontpage story in the Dom-Post – Orr went further, talking about the tax advice they might also offer. It wasn’t clear what expertise the Governor thought the Bank had in these areas – there is nothing in their research publications or speeches in recent years that suggests any – but I guess that doesn’t often deter the Governor.

But all that talk can’t have gone down well with the Minister, as the newsroompro newsletter this morning includes this

Ouch.

All seems not to be sweetness and light between the Governor and the Minister. But then they deserve each other really. Robertson was engaged in a transparent attempt to distract briefly from the three years of failure of his own government, writing to the Reserve Bank – sure to get headlines – rather than putting the hard word on his own boss and his ministerial colleagues. And Orr, who surely knows there is nothing there and how empty b(ii) really is – and who genuinely seems to think monetary policy should be focused on boosting aggregate demand in ways that lift inflation and employment, can’t help himself in openly trying to embrace a much wider role as adviser on all manner of things that really have nothing much to do with the Bank. Meanwhile, through this period we have had precisely no serious speeches or research papers on monetary policy, we have a central bank that fell back on LSAP partly because it didn’t think to do the basics and check that banks could operate with a negative OCR, and (of course, still) the invisible external members of the Monetary Policy Committee. A high-performing central bank and Monetary Policy Committee would have done a much better job over months of articulating a story, and explaining the place of monetary policy in the mix.

Then, of course, there was the question as to whether had the proposed amendment to b(ii) been in place back in March anything about monetary policy this year would have been different. Orr – probably diplomatically – avoided answering that, but of course the straightforward answer is no. That is so for two reasons. First – and this is a point Orr made in his MPS press conference – the threat to output, employment, and inflation in March was so large that the operational objectives the Minister has given the MPC would simply have impelled a significant easing in monetary policy. But the other reason – actually more an explanation for monetary policy choices than is often realised – is the forecasts. Back in March, hardly anyone (no one I’m aware) would have forecast the rise in house prices we’ve actually seen. Most probably expected – I did – something more like 2008/09, with a dip in prices for a time. So sitting in an MPC meeting in March with an amended b(ii) the house price issues would have appeared moot. Monetary policy would have been conducted just as it was. Oh, and not to forget my point earlier: no one knows what b(ii) means in practice anyway.

But of course if the Minister took any economic advice at all before sending his political theatre letter, he’d have known that too.

So change the Remit, or don’t, in this way and (a) it won’t make any difference to the conduct of monetary policy, and (b) it won’t change the fact that the reforms that might make a real difference now to land/house prices are all matters under the control of ministers already, backed by their majority in Parliament. If my kids can’t buy houses 10 years hence, it is going to be the fault of Ardern and Robertson, and not at all that of the Reserve Bank.

Yes, Robertson was clearly hoping to divert attention from Labour’s failures and clear the decks for an extended holiday until February. But Orr has returned service, how inconvenient of him. There are five sitting days before Christmas. The government could make a start now by pushing through legislation to require Councils to rezone land for housing and by suspending those parts of the RMA that impede housing development. But they will do nothing because they are incompetent and fearful of a backlash from those who have a vested interest in keeping things as they are, especially in regard to the RMA.

LikeLiked by 2 people

And now I see they plan to declare a “climate emergency” in Parliament next week: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/mps-will-next-week-vote-on-whether-or-not-parliament-should-declare-climate-emergency/JAV6PY5BV5MTXDMB4IAYIUIRGU/. A thoroughly useless gesture designed for UN consumption. How about a “housing emergency”? Yeah, right.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Jacinda Ardern and Grant Robertson want to win the next election. Jacinda likes her $450k salary and so does Grant Robertson on $350k. They have learned a do nothing approach keeps them in the centre and keeps them in government. People with houses want higher house prices. No one invests $1 million in a house and hope prices will fall.

LikeLike

Jacinda, in the House yesterday blamed National for the situation, a situation they’ve had three years to get on top of. They really are completely useless.

She needs reminding that they had the opportunity to support the reform of the RMA when they were in opposition. National couldn’t get the changes through because of resistance from the Maori Party. Now they’re flailing about blaming any one and any thing other than there own incompetence.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Phil Twyford announced Tier 1 cities before the election. 6 levels unrestricted builds in Auckland, Hamilton, Christchurch, Wellington etc. And that sparked a structural repricing and the current boom in the property market. Phil Twyford was demoted and lost his portfolio. If you want to build 10,000 houses a year, you need heights. More land is not the answer. Traffic congestion is a massive barrier towards living any further out.

LikeLike

Speaking of diverting attention (AKA blaming everyone else)

“Jacinda Ardern says public bears some responsibility for housing crisis after failed taxation attempts.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern is putting some onus on the public for the housing crisis, saying the Government had tried taxation to ease the soaring market three times without public support”

So many lies and half truths to cover up for incompetence

A/ The public actually supported capital gains tax – A 2017 ONCB poll found 58% supported a CGT and 34% opposed

B/ The CGT as proposed didn’t apply to family homes and hasn’t had any significant effect elsewhere

C/ Proposals that could have made a difference – RMA reform, immigration reform, abolition of the Auckland rural urban boundary and infrastructure bonds and increased height limits were ignored or not pursued but, apparently it’s all the general public’s fault.

https://www.tvnz.co.nz/one-news/new-zealand/jacinda-ardern-says-public-bears-some-responsibility-housing-crisis-after-failed-taxation-attempts

LikeLike

The problem as I see it is successive governments have wanted to have their cake and eat it too. At best, monetary policy can be used to constrain the demand side, but trying to finesse where the money supply goes is like trying to fill water bottles using a fire hose. So then you get all these layers of regulation like LVRs and bright line tests, which are equally ineffectual and most hurt those trying to get into the market. Then you have the Greens, assisted by a concerted campaign of the media in the last few weeks, calling for draconian capital taxes, which (to get a bit carried away with the analogies) is like drinking drain cleaner to get rid of a stomach bug.

The housing problem is supply side (notwithstanding broader concerns about the economic effects of immigration). You could define a well-functioning housing market as one in which supply is sufficient to meet the demand for reasonably priced housing, with “reasonably priced” being something like the global median price-to-income ratio rather than one of the highest in the world. That means more land development, more building consents and less costly building regulations – all of which are within the Government’s control.

Unfortunately, the Government seems intent on pointing the finger at everyone and everything other than those things they have control of. The only reason for this dishonesty is if you have no intention of dealing with the problem and wish to avoid the blame.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The really sad parts of the housing crisis is that the housing stock is generally in poor condition and funds that could be used to upgrade it and extend it are being used instead to bid up the price.

Meanwhile, those outside the market watch it moving further out of reach and the fools in the market think they’re better off when they are really just ballooning their balance sheets. And those who do own “investment” properties are often just slum landlords.

As more kiwis drop out of the housing market, there’s even less incentive for people to maintain the housing stock. why look after someone else’s asset? And I’ve yet to meet a landlord who even knows what a sinking fund is, or depreciation for that matter…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed it is true that the sharemarket and the property market are just ballooning numbers on a screen as I have a $200k wage that covers all of my daily spending requirements and the growing assets on the balance sheet is not drawn on. The increasing rents and falling interest rates also equates to a significantly higher tax bill this year.

Slum landlords rather more difficult with Healthy Homes. I will spend $20k per property on heatpumps, reroofing, painting and other maintenance which employ dozens of workers even with my small $9 million investment property portfolio. A booming market allows for a hefty spendup on my 11 properties.

LikeLike

The RBNZ is not completely blameless. The LVRs should have stayed on.

Figure 2.10 clearly shows the recent surge in house prices being mainly driven by investors.

https://www.interest.co.nz/news/108120/rbnz-notes-financial-stability-risks-associated-sky-rocketing-house-prices-doesnt-see

LikeLiked by 1 person

Important to keep monetary policy and bank prudential regulation distinct, as the legislation does.

On LVRs, agree that if financial repression is eased one will see more of the previously constrained activity (as happened when controls were lifted in the 80s). In the midst of the crisis in March/April with mortgage holidays and all sorts of govt support measures temporarily lifting the LVR limits was both wise and more or less inevitable (esp given that the case for controls was about exuberant lending and weak lending standards in economic boom times).

LikeLike

All good on mon pol tools being constrained. But what is the problem of debt to income limits? Many countries have them.

The measures the RBNZ took since March made sense in a world with significant uncertainty, with no clear prospect of a vaccine. Expectations since the start of November have changed, people and businesses can make plans again. Today’s world looks different, and the RB could act accordingly.

LikeLike

I agree that the March measures made sense.

I don’t spend much time on the Bank’s earlier DTI proposal but I usually find Ian Harrison’s critiques pretty persuasive.

Click to access Ian-Harrison-DTI-response.pdf

I noticed yesterday that Geoff Bascand sounded less than 100% enthusiastic about a DTI tool.

(What does slightly amuse me is that formally the RB does not need ministerial permission to deploy a DTI restriction but the media don’t seem to be aware of that.)

LikeLike

The banks already have a income limit based on 4 weeks vacancy factor built into rental income and a risk interest calculated at 6.5%. This interest rate dropped only 0.5% even when actual interest rates fell to now 2.39%. Income also is required to service plus repay a 30 year loan. A debt to income restriction is already a bank self imposed discipline.

The problem we have is the rubbish statistics that dumb economists use as a measure when they calculate income and compare with NZ debt. Income calculated by NZ Statistics is a local NZ income. It does not factor in the income of 1 million Kiwis that work overseas, derive a overseas income and do not pay NZ taxes but do buy up NZ property and do borrow from local NZ banks. Also there are 1 million migrants who will have overseas incomes that are not declared as NZ income but can be used for borrowing in NZ.

LikeLike

In other words, even though interest rates are at a all time low of 2.39% and likely continue to fall, your ability to borrow is still unchanged because the bank still require income to service 6.5% plus repay a 30 year loan in order to lend.

LikeLike

Regardless of the flavor of the current government, I don’t see how any political will can ever be developed to materially reduce the price of the major asset of the majority of New Zealand families.

Are there any comparable polities who’ve dealt with this successfully?

LikeLike

It is a line I’ve often used to optimists, that I’m not aware of any country/region that having once so badly messed up their housing market with land use restrictions etc has unwound it.

I started using the line as a prod to see if anyone had counterexamples. I’m now convinced there are none.

On the other hand, and being briefly a little more optimistic, this sort of systematic distortion is relatively now and a huge problem in a relatively small number of countries (at least as I understand it). So there is an opportunity to be first. Any successful reform – outside a deep deep crisis – is likely to have to be part of some package of measures, including compensation for some losers, to help build and sustain a coalition that will support/tolerate those measures.

On the other hand, there is also the rising generation. Speaking personally, having paid off my mortgage, I would not feel one whit poorer if house prices halved, since I intend to live here for life. And I am increasingly angry – a word I use very sparingly – about what governments have done to the house purchase prospects of my kids. As mid-teens, only a few decades ago they would reasonably be looking to buy in 10 years or so. In our not-that-large cities, at present that looks like a pipedream.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As you have a debt free property similar to 33% of households, you will already have planned the transfer of that equity into the hands of your children either through your will or through your family trust by being beneficiaries of your family trust. As I have a portfolio of properties, I have already transferred a property plus cash savings to my daughters. The one with a wage I have gifted equity plus cash for her to purchase her first property at age 26, similar age to me when I bought my first property. My younger daughter I have already gifted cash of $100k into her bank account. Nothing much has changed for my 2 kids so I am at a loss to understand as to why you would be angry and think your kids are not able to buy as you have bought?

LikeLike

I am in a similar situation, our home is mortgage free and we have no desire to move. Even if we did, we would aim to go from mortgage free to another mortgage free situation. Therefore the actual value of the home has no real meaning.

Those not owning a home have a different reality, staring at an impossible task. The concern is, once the borders and the world opens up, the brain drain will become a major problem. Why stay as a permanent renter when there are so many opportunities to get ahead elsewhere. NZ will probably lose its best, only to try and replace them with those that find a country where never owning a home is still better than what they have.

LikeLike

New Zealand will always lose its best simply because our education institutions train them for highly skilled jobs which simply do not exist or just not enough jobs to employ them and provide advancement.

LikeLike

Australia’s housing system needs a big shake-up: here’s how we can crack this – https://theconversation.com/australias-housing-system-needs-a-big-shake-up-heres-how-we-can-crack-this-130291

also

Ten lessons from cities that have risen to the affordable housing challenge – https://theconversation.com/ten-lessons-from-cities-that-have-risen-to-the-affordable-housing-challenge-102852

LikeLike

Hi Michael. Hope you are doing ok. If you get a chance I’d be interested in your comment on this report. https://nzier.org.nz/publication/could-do-better-migration-and-new-zealands-frontier-firms

LikeLike

Am hoping to write something about it tomorrow.

LikeLike

Great. Look forward to reading your post.

LikeLike