I’ve written various pieces over the years on the Productivity Commission, both on specific papers and reports they have published, and on the Commission itself. I was quite keen on the idea of the Commission when it was first being mooted a decade or so ago. There was, after all, a serious productivity failure in New Zealand and across the Tasman the Australian Productivity Commission had become a fairly highly-regarded institution. But even from the early days I recall suggesting that it was hard to be too optimistic about the long-term prospects of the Commission, noting (among other things) the passing into history of the early Monetary and Economic Council, which had in its day (60s and early 70s) produced some worthwhile reports. In a small, no longer rich, country, maintaining critical mass was also always going to be a challenge, and agencies like The Treasury might be expected to have their beady eye on any budgetary resources allocated to the Commission, and on any good staff the Commission might attract or develop (a shift to another office block at bit further along The Terrace was unlikely to be much of a hurdle).

What I probably didn’t put enough weight on in those early days was the point that if governments weren’t at all interested in doing anything serious about New Zealand’s decades-long productivity failure, there really wasn’t much substantive point to a Productivity Commission at all, unless perhaps as something to distract the sceptics with (“see, we have a Productivity Commission”).

Ten years on, it isn’t obvious what the Commission has accomplished. There have been a few interesting research papers, some reports that may have clarified the understanding of a few policy points. But what difference have they made? Little, at least that I can see. Is the housing market disaster being substantively addressed? Is the state sector better managed? Is economywide productivity back on some sort of convergence path? Not as far as I can tell. Mostly that isn’t the Commission’s fault, although my impression is that the quality of the reports has deteriorated somewhat in recent years. But if politicians don’t care about fixing what ails this economy, why keep the Commission? It might be no more pointless than quite a few other government agencies and even ministries, but they all cost scarce real resources.

For the last 18 months I’ve been looking to appointment of the new chair of the Commission, replacing Murray Sherwin who has had the job for 10 years, as perhaps one last pointer to the seriousness – or otherwise – of Labour about productivity issues. There wasn’t much sign the Minister of Finance or Prime Minister cared much at all – or perhaps even understood the scale of our failure – but just possibly they might choose to appoint a new chair of the Productivity Commission who might lead really in-depth renewed intellectual efforts to address the failure, perhaps even in ways that might, by the force of their analysis and presentation, make it increasingly awkward for governments (Labour or National) to simply keep doing nothing. I wasn’t optimistic, partly because I’d watched Robertson and Ardern do nothing for several years, but also because – to be frank – it really wasn’t clear where they might find such an exceptional candidate even had they wanted one.

But then they removed all doubt last week when they announced the appointment of Ganesh Nana as the new chair. There is a strong sense that he is too close to the Labour Party. If that wasn’t ideal, it might not bother me much – especially given the thin pickings to choose a chair from among – if it were matched with a high and widespread regard among the economics and policy community for his rigour and intellectual leadership, including on productivity issues. Or even perhaps if he knew government and governent processes inside out (Sherwin, after all, was a senior public servant rather than himself being an intellectual leader). I don’t suppose the Nana commission is simply likely to parrot lines the Beehive would prefer – and can imagine some of Nana’s preferences being uncomfortable for them from the left – but this is someone who has spent 20+ years in the public economics debate in New Zealand, from his perch at BERL, and yet as far as I can tell his main two views of potential relevance are that (a) inflation targeting (of the sort adopted in most advanced economies) is a significant source of New Zealand’s economic underperformance, and (b) that a much larger population might make a big difference (notwithstanding use of that strategy for, just on this wave, the last 25 years or so.

Then there was this bumpf from the Minister’s press statement announcing the appointment

Ganesh Nana said he is excited to take up the position and looks forward to working with other Commission members and staff to focus on a broad perspective on productivity.

“Contributing to a transformation of the economic model and narrative towards one that values people and prioritises our role as kaitiaki o taonga is my kaupapa. This perspective sees the delivery of wellbeing across several dimensions as critical measures of success of any economic model.

“Stepping into the Productivity Commission after more than 20 years at BERL will be a wrench for me and a move to outside my comfort zone. However, this opportunity was not one I could ignore as the challenges facing 21st century Aotearoa become ever more intense.

“The role and nature of the work of the Commission is set to change in light of these pressing challenges. I am committed to ensure the Commission will increasingly contribute to the wider strategic and policy kōrero,” Dr Nana said.

Whatever that means – and quite a bit isn’t at all clear to me – it doesn’t suggest any sort of laser-like focus on lifting, for example, economywide GDP per hour worked, in ways that might lift material living standards for New Zealanders as a whole.

(And then there was the unfortunate disclosure in the final part of the Minister’s press statement that the government has agreed that while functioning as a senior economic official, paid by the taxpayer, Nana is to be allowed to retain his almost half-share in his active economic consulting firm BERL. There is the small consolation that the Commission itself will not contract any business with BERL, but that should not be sufficient to reassure anyone concerned about what is left of the substance or appearance of good governance in New Zealand.)

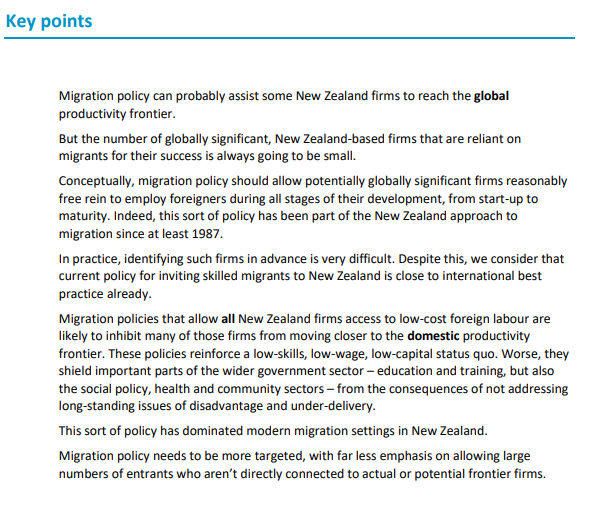

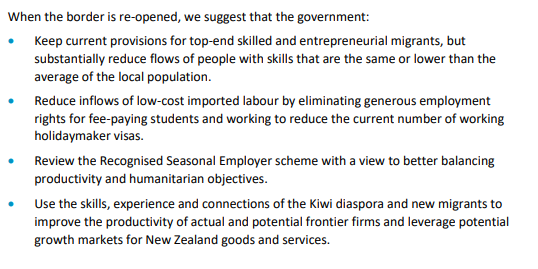

A couple of weeks ago the Productivity Commission released a draft report on its “Frontier Firms” inquiry. The Commission does not control the inquiries it does – they are chosen by the government – and this one also seemed a bit daft to say the least, since “frontier firms” always seem much likely to arise from an overall economic policy environment that has been got right, rather than being something policymakers should be focusing on directly. But the Commission might still have made something useful, trying to craft something a bit more akin to a silk purse from the sow’s ear of a terms of reference.

I had thought of devoting a whole post to the draft report, and perhaps even making a formal submission on it, but since the report will be finalised under the Nana commission that mostly seems as though it would be a waste of time. And there is the odd useful point in the report, including the reminder that our productivity growth performance has remained dreadful by the standards of other modestly-productive advanced economies, and that we have relied on more hours worked, and the good fortune of the terms of trade, to avoid overall material living standards slipping much recently relative to other advanced economies. Productivity growth – much faster than we’ve achieved – remains central to any chance of sustainably lifting those material living standards and opening up other lifestyle etc choices.

But mostly the report is a bit of a dog’s breakfast. Just before the draft report was released the Commission released a short paper on immigration issues that they had commissioned. I wrote about that note, somewhat sceptically, at the time – sceptical even though the gist of the author’s case might not be thought totally out of line with some of my own ideas. It turned out that the Fry and Wilson work was the basis for the Commission’s own discussion of immigration in the draft report, a discussion that neither seems terribly robust nor at all well-connected to the “frontier firms” theme of the report. Perhaps the RSE scheme has problems, perhaps some low-skilled work visas are issued too readily, but…..apple orchards and vineyards didn’t really seem to be the sort of “frontier firms” the Commission had in mind in the rest of the report.

Perhaps my bigger concern was about their attempts to draw lessons from other countries. They, reasonably enough, suggest that there might be lessons from other small open advanced economies, perhaps especially relatively remote ones. But then they seem to end up mostly interested in places like Sweden, Finland, Denmark and the Netherlands – all of which are in common economic area that is the EU (two even with the euro currency, most with no disadvantages of remoteness). I don’t think there was a single reference to Iceland, Malta, or Cyprus. Or to Israel – that country with all the high-tech firms and a productivity performance almost as bad as ours. And – though it might not be small, it has many similar characteristics to New Zealand – no mention at all of Australia. Remote Chile, Argentina and Uruguay get no mention – even though two of those three have had strong productivity growth in recent times – and neither, perhaps more surprisingly, do any of the (mostly small) OECD/EU countries in central and eastern Europe, many of which are now passing New Zealand levels of average labour productivity.

There wasn’t any systematic cross-country economic historical analysis or a rigorous attempt to assess which examples might hold what lessons for New Zealand. Instead, there a mix of things that might be music to the ears of a government that wants to be more active, and perhaps to punt our money again on the emergence of some mega NZ excellent firm(s) – without any demonstrated evidence that it (or its officials) can do so wisely or usefully – plus the odd thing that must have appealed to someone (eg the material on immigration – a subject that might still usefully warrant a full inquiry of its own, if the government would allow it, and when better than when we are in any case in something of a hiatus).

This will probably be the last post for this year, so I thought I’d leave you with a couple of charts to ponder.

The first is a reminder of just how little we know about what is going on with productivity – or probably most other aggregate economic measures – right now. As regular readers will know, I have updated every so often an economywide measure of labour productivity growth that averages the two different real GDP series (production and expenditure) and indexes of the two measures of hours (HLFS hours worked, QES hours paid).

First, there is the huge difference in the two GDP measures. Whichever one one uses – but especially the expenditure measure – suggests a reasonable lift in average labour productivity this year (on one combination as much as 5 per cent). In the period to June there was an argument about low productivity workers losing their jobs, averaging up productivity for the remainder, but how plausible is that when hours are now estimated to be down only 1% or so on where they were at the end of last year (much less than, say, the fall in the last recession)? And thus how plausible is the notion of an acceleration in productivity growth given all the roadblocks the virus, and responses to it, have put in place this year. And although SNZ’s official population estimates have the population up 1.5 per cent this year (to September), if we take the natural increase data and the total net arrivals across the border data, they suggest a very slight drop this year in the number of people actually in New Zealand. I’m not sure, then, which of the economic data we can have any confidence in, although I’ll take a punt that the single least plausible of these numbers is the expenditure GDP one, and any resulting implication of any sort of real lift in productivity this year. SNZ has an unenviable job trying to get this year’s data straight.

But, of course, the real productivity challenge for New Zealand was there before Covid was heard of, and most likely be there still when Covid is but a memory. As we all know, New Zealand languishes miles behind the OECD productivity leaders (a bunch of northern European countries and the US), but in this chart I’ve shown how we’ve done over the full economic cycle from 2007 to 2019 relative not to the OECD leaders but to the countries that in 2007 either had low labour productivity than we did, or were not more than 10 per cent ahead of us then. For New Zealand I’ve shown both the number in the OECD database, and my average measure (which has the advantage of being updated for last week’s GDP release).

Whichever of the two NZ measures one uses, we’ve done better only than Greece and Mexico. Over decades Mexico has done so badly that the OECD suggests labour productivity in 2019 was less than 5 per cent higher than it had been in 1990. Even Greece has done less badly than that.

(As a quick cross-check, I also looked at the growth rates for this group of countries for this century to date. We’ve still done third-worst, beating the same two countries, over that period.)

It is a dismal performance. And there isn’t slightest sign that our government cares, or is at all interested in getting to the bottom of the problem, let alone reversing the decades of failure. Talking blithely about alternative measures of wellbeing etc shouldn’t be allowed to disguise that failure, which blights the living standards of this generation and the prospects of the next.

(And, sadly, there is no sign any political opposition party is really any better.)