Way back on 16 March, the day before the government brought down the first of its pandemic economic response packages, I ran a post here in which – among other strands of an approach to the rapidly worsening economic situation – I suggested that the government should legislate quickly to provide, for the coming year, a guarantee that no one’s income would fall below 80 per cent of what it had been in the previous year. The proposed approach was to treat individuals and companies in much the same way. The underlying idea was to provide some certainty – to individuals, firms and lenders – without offsetting all losses (society was going to be poorer) and without locking people in to employment or business relationships that may have been sensible/profitable previously, but which wouldn’t necessarily be in future. And to recognise that individual firms and people are better placed to reach those judgements – about what makes sense for the future, what makes sense (say) to borrow to support – that government ministers or officials.

I knew that any such scheme might be very expensive, and rereading the post I see that I proposed it even though I was talking about economic scenarios for potential GDP losses that were materially worse than most think we will now actually face. But part of the mindset was the parallel with ACC – our no-fault accident compensation system. Being able to treat people in a fairly generous way when a serious pandemic – that was no one’s fault – hit could be conceptualised as one of the bases for the low-debt approach successive governments had taken to fiscal policy over recent decades. And it did not require governments to pick winners – firms they thought might/should flourish – or pick favourites.

Since it was sketch outline of a scheme, dreamed up over the previous few days, I was always conscious that there were lots of operational details that would have to be worked through before an idea of this sort could be implemented, and any scheme would need to be carefully evaluated for the risks that might lie hidden just beneath the surface. But evaluated not relative to standards of perfection, but relative to realistic alternatives approaches in a rapidly unfolding crisis.

I wrote a couple of other posts (here and here) touching on aspects of the pandemic insurance idea, and as I reflected a bit further and discussed/debated the idea with a few people, I suggested some potential refinements, including greater differentiation between companies and individuals. Other people, here and abroad, also suggested ideas that had some similarities in spirit to what I was looking to achieve.

Of course, nothing like the pandemic insurance scheme was adopted. Instead, we had a flurry of schemes and of individual bailouts, the main attraction of which seemed to be a steady stream of announceables for Cabinet ministers in election year (generally a negative in terms of the public interest, in which similar cases should be treated similarly), all while offering little or no certainty to individuals, firms, or their lenders.

I’ve continued to regard something like the pandemic insurance scheme as a superior option that should have been taken, but mostly I moved onto writing about other things. But the return of community-Covid, more or less severe government restrictions on economic (and other) activity, and arguments about whether and for how long the wage subsidy should be renewed only reinforced that sense that there would have been a better way. But a few tweets aside, I hadn’t given the issue much thought for a while until a few weeks ago a TVNZ producer got in touch to say that they had found reference to the pandemic insurance idea in an OIA response they had had from The Treasury, and asking if I’d talk to them about it.

It was only late last week that I got to see the response Treasury had provided (Treasury having fallen well below their usual past standards has still not put the response – dated 12 August – on their website (or even acknowledged my request for a copy of the same material). A little of the subsequent interview with TVNZ was aired as part of their story on Saturday night, itself built around the notion that the government had rejected this (appealing sounding) idea.

OIA Response Pandemic Insurance etc

The TVNZ OIA request had actually been for material on “helicopter payments”, which was refined to mean

“one-off payments made by the Government to citizens with the purpose of stimulating the economy,

(which in some respects does not describe the pandemic insurance idea well at all).

And yet most of the material in the quite lengthy OIA response (77 pages) turned out to be about the work The Treasury had undertaken on the pandemic insurance idea over the couple of weeks from 7 April, including some advice to the Minister of Finance.

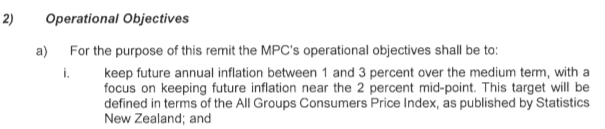

There seems to have been quite serious interest in the option, and there is paper to the Minister of Finance providing a fair and balanced outline of the scheme – merits and risks – dated 9 April

and suggesting that if the Minister was seriously interested Treasury would do more work and report later in the month. Although there is no more record of the Minister’s view, he must have been sufficiently open for more work to have been done, including drawing in perspectives from operational agencies (including IRD and MSD) on feasibility and operational issues.

My impression is that Treasury did a pretty good job in looking at the option.

That final paragraph was always one of the key attractions to me.

As I went through the papers, I didn’t find too many surprises. The issues and risks official raised were largely the ones I’d expected – including, for example, the risk that some people might just opt out of the labour market this year and take the 80 per cent guarantee, and issues around effective marginal tax rates for those facing market incomes less than 80 per cent. Perhaps the one issue I hadn’t given much thought to was a comment from IRD about the risk of firms being able to shift revenue and/or expenses between tax years, with the observation that existing rules were not really designed to control that to any great extent. But, and operating in a second-best world, the officials involved generally seem to have regarded few of these obstacles as insuperable, bearing in mind the pitfalls of (for example) the plethora of alternative schemes.

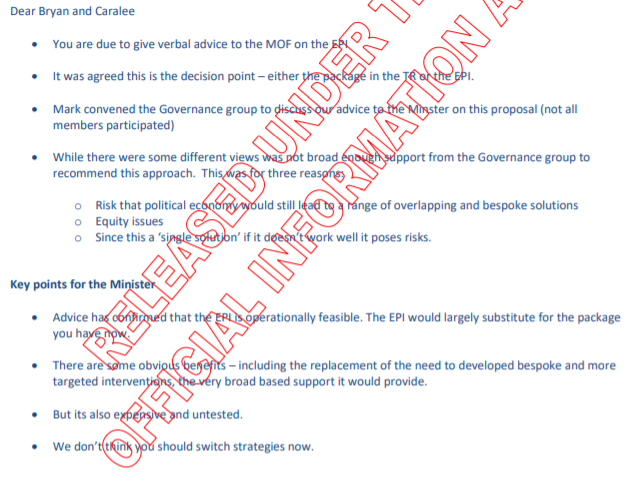

The work seems to have come to an end on or about 23 April with Treasury finally deciding not to recommend the pandemic insurance approach. This email is from a Principal Advisor heavily involved in the evaluation to the Secretary and key (on the Covid issues) Deputy Secretary.

It probably shouldn’t surprise readers that I think the wrong call was made in the end, but equally it is probably not that surprising that the decision went the way it did. One reason – not, of course, acknowledged in the Treasury papers – is how slow officials were (across government) in appreciating the seriousness of what was already clearly unfolding globally – and as a major risk to New Zealand – by the end of January. As I’ve noted before there is no indication in any of the papers that have been released, or public comments at the time, that (for example) Ministers or the heads of the key government departments had begun serious contingency planning – devoting significant resource to it – any time before mid-March. This particular work didn’t get underway until well into April, by when a great deal had already begun to be set in stone, and when rolling out bite-sized new announcements – robust or not – no doubt seemed, and was, easier than a new comprehensive approach.

As it happens, even though there was a great deal of concern back in April about the affordability of the pandemic insurance scheme, with the benefit of hindsight there is a reasonable argument that it could even have been cheaper than the approaches actually adopted (GDP losses having been less severe, on a sustained basis, than feared in April), which in turn might have left more resources for the stimulus and recovery phase (pandemic insurance – like wage subsidies – was always more about income support and managing uncertainty in the heat of the crisis than about post-crisis recovery stimulus).

From my perspective, the post was mostly about recording my pleasant surprise at how seriously the pandemic insurance idea (mine, and some other variants) was taken by officials, and by what appears to have a pretty good job in evaluating it as an option, in what will have been very trying and pressured times.

From this vantage point – with the advantage of knowing how the first six months of the virus went, and with a sense of the economic ramifications – I still reckon it would have been a better approach. And yet – and I don’t recall seeing this in Treasury’s advice (perhaps it isn’t the thing for officials to write down) I can also see political pitfalls – around very large payouts to some companies, even if they weren’t gaming the system – that might have made it impossible, and unsustainable if tried, without (at least) a very strong degree of political leadership and marketing that such a no-fault no-favour approach was a better way to have gone. As I noted in an earlier post, I’d have hated having the Crown pay out to casino companies, but I would have endured for the sake of a fair across the board scheme. But every single person, every single lobby group, would have found some potential recipient to excoriate.

The TVNZ interviewer asked me about the pandemic insurance idea still had relevance for the future. My initial response to him was that yes it did, and that we might be much better off to have the infrastructure required to make it work in place and on the shelf ready to go for when future pandemics happen. Taxes will, after all, be a bit higher than otherwise as we gradually lower debt ratios, amid repeated talk of being ready for the next major adverse event, whether earthquake, volcano or pandemic.

And yet reflecting on it again over the weekend, I’m no longer quite so confident of that answer. More detailed work, and more thought, is probably required once this pandemic is behind us to strike the right balance – individuals vs firms, generosity in a no-fault shock vs moral hazard as just some of the examples of issues to be thought through, and planned for, ideally in a way that would survive contact with a new real severe adverse shock.