The Reserve Bank’s Monetary Policy Statement is due out on Wednesday. It will be interesting to see what tone the MPC comes out with. Quite a bit of the recent media commentary in New Zealand has been rather upbeat, for reasons that aren’t fully clear. No one seems to expect the MPC to do much that might make a difference, although there will be interest in what the Committee has to say on its handwaving supplementary tools (that do little useful), the Large Scale Asset Purchase programme and, for example, the idea of buying foreign assets. The latter, if launched at some stage, might get them some headline effects for a day or two – as happened when we tried fx intervention back in 2007 – but beyond that is likely to be even less effective than the LSAP.

Where the MPC could still be of us, even if they aren’t going to change the OCR, is to apply to refreshing dose of bleak reality to the discussion of New Zealand’s economic situation. I don’t suppose they will go very far in that direction – after all, doing so wouldn’t help their ideological allies in the current election campaign – but they might still help that they shift the ground somewhat. Even the Minister of Finance has been heard recently reporting that The Treasury – whose own PREFU numbers are due out next week – are now really quite pessimistic on the world economy. And a small, moderately open, economy isn’t that well-positioned if (a) the rest of the world is doing poorly, and (b) domestic macro policy is doing less than usual in a downturn.

The latest expectations data was a reminder as to just how little monetary policy has done this year. Take inflation expectations as just an example.

The ANZ’s survey of the year-ahead inflation expectations of a reasonably large sample of their business customers hasn’t produced a result as high as 2 per cent since May last year. As recently as their February survey – mostly taken before the February MPS when the Reserve Bank was sufficiently upbeat they adopted a slight tightening bias – year ahead expectations were as high as 1.89 per cent. Now those expectations are about 1.4 per cent, a long way below the target midpoint the MPC is supposed to focus on.

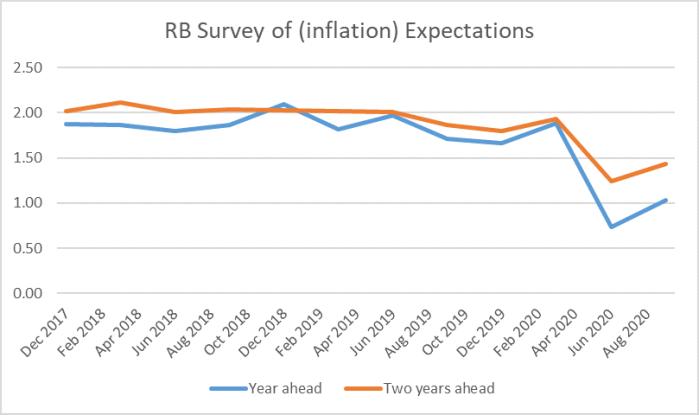

What about the Reserve Bank’s own survey of a smaller sample of supposedly relatively expert observers? We got the latest read on that last week.

As expected, there is a slight recovery in the latest survey, but both lots of expectations are a long way below the target midpoint. If you were charitable you might argue that the year ahead outlook was at least in part still beyond the Bank’s control, but there is ample opportunity for the Bank to have inflation back to 2 per cent by the year to June 2022. But respondents don’t believe they will.

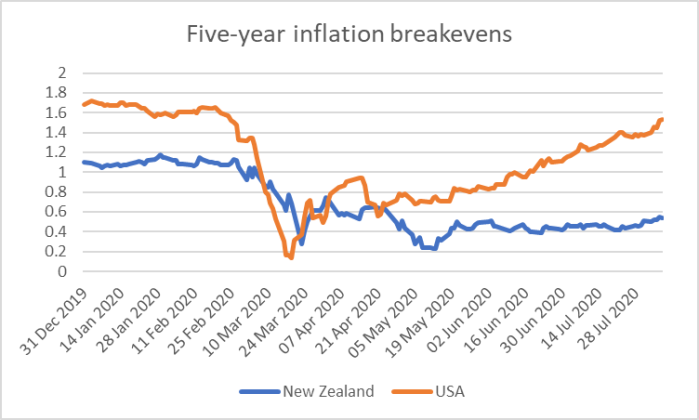

And what about market-based measures? These are the five year breakevens (from the indexed and conventional government bond yields) for the United States and New Zealand.

The breakevens fell sharply in March, especially in the US – the focal point for the stresses in government bond markets. But since then US breakevens have retraced most of this year’s falls. The New Zealand picture is very different: not only did the implied breakevens start the year miles below the inflation target, but that gap has widened substantially further this year, with little sign now of any convergence/correction. These implied expectations are 55 basis points lower than they were at the end of last year, or than they were when the MPC was setting policy in February.

Perhaps the best thing about the Reserve Bank’s Survey of Expectations is that it asks the same respondents about a bunch of macro variables, not just about inflation. If we assume those people are each answering somewhat consistently, we can look at one set of answers in light of others. For example, we know that the OCR has been cut by only 75 basis point this year, but there is also a question about where respondents think the OCR will a year ahead. Since the survey done in early February, those expectations have fallen by 78 basis points. That is actually a bit less than the fall in those same respondents’ year-ahead inflation expectations. Even if you think (as the Bank typically did) that the two year-ahead measure is more important, you are left with results in which these respondents think real interest rates have fallen only perhaps 25-30 basis points. It is a derisory change in the face of a shock of this magnitude.

What about government bond rates? Well, we hear a great deal from the Bank – and some of their market acolytes – about the difference the LSAP is making. But how much have year-ahead expectations of the long-term bond rate fallen since February, even taking account of the LSAP (actual and expected)? A mere 54 basis points. To be sure, we do not know the counterfactual – without the bond-buying actual and expectation bond yields might be higher, but the bottom line remains that yields have not fallen much, especially in real terms.

Respondents are also asked about GDP growth and although these responses seem to have got no media coverage in some respects they are the most disconcerting of them all. Respondents expect real GDP growth of 4.24 per cent in the four quarters to June 2021 (the median response is actually much lower at only 3 per cent) and 2.77 per cent over the following four quarters. Those numbers might not seem so bad until you realise that the (generally expected) trough in GDP will have been in the June quarter 2020. It is quite likely that GDP in the four quarters to June 2020 will have fallen by perhaps 15 per cent. A rebound of only 7 per cent over the following eight quarters would be alarmingly bad. The question is quite clearly posed: it is not an annual average growth rate that was asked for, although I suppose some may have misinterpreted it that way. However respondents answered the GDP question- and there is a huge range of estimates for the year ahead (from -18 per cent to 24 per cent) – respondents expect the unemployment rate to remain high.

The Bank introduced a couple of interesting new questions to the latest survey (I hope they become standard features, and that the results are reported on the main tables on the website). First, they asked respondents what they expect the OCR to be in June 2030 – ten years’ hence. The point here is not that there is anything very special about the specific June 2030 date, but that it is far enough ahead that one could expect respondents to look beyond the current crisis or evident cyclical pressures and think mostly about the long-term structural features of the economy. The range of estimates was wide – from 1 per cent to 4.5 per cent – with a median of 2.5 per cent. My own response to that question was 2.25 per cent, but since my 10 year ahead inflation expectations (1.5 per cent) were lower than those of the median respondent (2 per cent) I was a bit surprised to find that I had an above-median estimate of the neutral OCR.

(It would be interesting to invite the MPC members to follow the lead of the FOMC and publish their individual – unnamed – estimates of the neutral OCR.)

The other new question asked respondents to estimate the average OCR for the next 10 year. Again, the median response (1.5 per cent) was higher than my response (1 per cent), a difference likely to be mirrored in a difference in inflation expectations).

If these responses to the Reserve Bank survey capture anything useful at all, they should really be quite concerning to the Governor, to the Monetary Policy Committee, and to those with the legal responsibility for holding the Bank to account (that’s you Reserve Bank Board and Grant Robertson). Inflation is expected to be well below target, unemployment is expected to remain worryingly high, the recovery in GDP is expected to be pretty feeble at best, and hardly anyone expects that the Bank will manage to establish any material policy leeway in the period before the next economic downturn hits. It is a pretty clear case where the informed respondents do not act (write down expectations) as if they believe the Bank is adequately doing its job.

Now perhaps on Wednesday the MPC will come out with some much more upbeat story, and tell us reasons why the views of survey respondents should be discounted. But if anything at the time of their last MPS, the Bank was more pessimistic than survey respondents, even though their official line has been the monetary policy is providing large amount of stimulus.

Now, of course, the Committee likes to abdicate its responsibilities and put everything on fiscal policy. But that isn’t the way the regime is supposed to work. Rather, governments set fiscal policy and then the MPC is supposed to do whatever it takes (loosening or tightening) to deliver the inflation target the government has set out for them. Respondents to the Bank’s survey know all about fiscal policy, and yet they conclude that the Bank is not acting to do its job, isn’t acting consistent with getting inflation promptly back to 2 per cent or – for that matter – with quickly re-establishing full employment. The peak contribution to fiscal policy is already passing, monetary policy could have been aggressively deployed months ago to be in a position to take up the slack. Instead, we sit here now with real interest rates barely down much at all, a real exchange rate that hasn’t budged, and yet with really worrying – and remediable – economic and inflation outcomes in prospect.

I’m sure many readers are inclined to discount the significance of inflation expectations. I’m not one of those who runs a model in which inflation expectations directly set inflation outcomes, but when both expectations (all measures) of inflation are below target and unemployment is well away from full employment, what it tells us is that monetary policy simply isn’t being used to the full. There is a reasonable debate to be had about whether some countries, or the world, might emerge from this crisis with much higher – troublingly high, or (to some) usefully high – but when there is no indication at all, from surveys or market prices, that inflation is even likely to be at target, let alone far overshooting it, we should be able to expect more from the Reserve Bank, not just some handwringing exercise – from the macro-stabilisation agency – suggesting that the unemployment is someone else’s problem.

In this case, notably, we need deeply negative interest rates. I’ve seen some banks suggesting that interest rates will eventually go a bit negative because more stimulus is needed. But it is clear – including from those banks’ own commentaries – that that stimulus/support from monetary policy is needed now, not – even then in half-measures – sometime next year.

Michael what do you say to the most common response I see to the suggestion we need negative interest rates – that they haven’t worked overseas and we see little sign of increased usage of them?

LikeLike

On the first leg, I’d say they have worked – they haven’t been used v aggressively, but places like Sweden and the euro-area and Japan were back to full employment prior to Covid, and very low interest rates helped (but bear in mind rates were never v negative).

On the second strand of the question, I don’t have a particularly good answer, altho in no advanced country do we see macro policy being aggressively set to get countries back quickly to full employment. Central banks and govts seem v reluctant to try the “deeply negative” route, and the parallel I drew in a post a few months ago was with the reluctance of countries to go off the gold standard in the great depression – and yet as and when they did their economies typically recovered.

LikeLike

I can understand why the gold standard became more a hindrance to monetary stability when it is hoarded and gold prices rises, the result is that currency pegged to the gold standard would also be hoarded. Afterall the intent of cash is to facilitate commerce and international trade and not a keepsake to increase wealth.

Similarly we do not want negative interest rates because there must be a cost to the bank to hold cash deposits which would be recouped through on lending to borrowers otherwise in these troubled times the tendency would be to hoard the cash and making a revenue from hoarding rather than release it to facilitate lending liquidity and earning an interest revenue.

LikeLike

On your second para, negative interest rates work in part by charging banks to hold deposits at the Reserve Bank (ie paying a negative interest rate), to disincentivise “hoarding” and to encourage banks to lower their own deposit and lending rates.

LikeLike

Looking at the the RBNZ Balance Sheet, the deposits Under Financial Liabilities of $41.6 billion in June 2020 looks like a book balancing entry of the NZ Treasury bond buying. The increment from last year June 2019 is almost equal the $22 billion NZ Treasury bond buying from local banks. I highly doubt that this is actual local bank deposits with the RBNZ but more a book balancing entry. After all printing cash still requires a double entry.

The likely Balance sheet entries are.

The initial cash creation book entry

Dr Cash – $22 billion

Cr Deposits – Financial Liabilities – $22 billion

The NZ Treasury bond buying from local banks.

Dr Securities – large scale asset purchase – $22 billion

Cr Cash – $22 billion

Note that the cash goes straight to the local banks in exchange for the purchase of NZ Treasury bonds and not likely held as a Deposit at the RBNZ. Personally I would have called the book entry a Equity Reserve rather than an entry to Deposits – Financial Liabilities.

LikeLike

See also ‘Box 1’ within the latest Bank of England monetary policy report

LikeLike

I expect the MPC and the announcement this week will maintain a very cautious / timid tone… one cannot offend the Tree God himself and with the election campaign now underway the money has to be on now change at all….

Depressing….

LikeLike

You mention that the OCR was reduced by “only” 75 basis points, completely overlooking the fact that the OCR was already at historic lows, having been recently dropped by a further 75 basis points the previous year. As I have previously outlined there are numerous reasons why negative rates – especially deeply negative interest rates could have hugely damaging effects and perverse side effects and this is surely why central banks in Australia, UK, US, Canada have been wary of using them. As numerous commentators have repeatedly pointed out the very low level of interest rates is not a constraint to business investment and lower still rates are likely to be ineffective. But, I would add, they are a red rag to the property market. Ultra low rates forcing savers into risky investments (other than property), in a time when risks are higher anyway seems a perilous policy.

Recently the ASB made these observations:

We nevertheless remain sceptical on whether the benefits of a negative OCR outweigh the costs. There is a considerable body of evidence (see our earlier paper) suggesting that the effectiveness of interest rate cuts tends to diminish the lower rates go. Internationally, retail deposit rates don’t tend to fall below zero when wholesale rates are negative. Generally, mortgage rates do tend to decline as the policy rate falls. However, this means that extended periods of negative interest rates squeeze net interest margins, and bank profitability can suffer. As a result, negative interest rates can interfere with the functioning of banking systems reliant on deposit funding and impair the ability of some banks to supply credit – the opposite of what monetary easing aims to do.

Moreover, banks may actually increase their retail borrowing interest rates in order to recoup the cost of holding reserves at negative interest rates. Recent evidence even suggests that zero interest rates may be more effective than negative rates in bringing forward economic activity. The experience offshore with negative interest rates had been decidedly mixed and does not exactly inspire confidence. It is telling that the US Federal Reserve, Reserve Bank of Australia, and the Bank of Canada have been publicly sceptical on the benefits of negative policy interest rates.

LikeLike

What happend in 1971 Michael?

https://wtfhappenedin1971.com/?fbclid=IwAR2Ds5VeCeDvmCnoAgGZjI5nDNPRR7P2zAWFKYs55DsQNYucCf6fFqDENcM

LikeLike