Adrian Orr is now 7.5 months into his term as Governor and we still haven’t had an on-the-record speech from him about either main strand of his responsibilities: monetary policy or financial supervision and regulation. Is he just not engaged on these issues?

But yesterday, his deputy Geoff Bascand delivered – in Australia – a substantive speech on financial stability issues. There were a few good elements in the speech. For example, I was pleased to see this in the conclusion

The capital review gives us all an opportunity to think again about our risk tolerance – how safe we want our banking system to be; how we balance soundness and efficiency; what gains we can make, both in terms of financial stability and output; and how we allocate private and social costs.

It may be that the legislation underpinning our mandate can be enhanced, for example, by formal guidance from government or another governance body, on the level of risk of a financial crisis that society is willing to tolerate.

At present, the legislation is drafted so broadly and loosely that a single unelected and unaccountable official gets to make any such choices. He (as it typically is) gets to make choices in a pretty much unconstrained way and we (including our elected political leaders) just have to live with the consequences. Whether the sort of formal guidance Geoff refers to in that second paragraph is (meaningfully) feasible is open to question, but we need to improve on the current situation. If such guidance isn’t feasible – if society can’t write down its preference and give them as a mandate for the technocrats – the big decisions around banking supervision policy frameworks (as distinct from the application of them to individual institutions) should be made by elected politicians (the Minister of Finance).

But, sadly, most of the speech just wasn’t that good. It had plenty of politicially popular lines, and there was even the obligatory reference to the Reserve Bank as a tree god. On climate change we had this

Climate change presents significant financial stability risks both through the direct implications of physical events for insurers, farmers and households, the indirect effects on insurance availability and property values, and through the potential social and economic disruption it promises.

We are working on developing a climate change strategy, which will be informed by discussions with banks and insurers in due course. Our role as a regulator is to try to ensure that financial institutions are adequately managing these risks, even though the horizon for their realisation could be decades away.

Given that the best evidence for New Zealand is that projected increases in global temperature are probably neutral and at best slightly positive for New Zealand in economic terms, and that all sorts of relative price changes occur every year changing the economics of all manner of businesses banks might have lent on, all this should amount to nothing. But we know the Governor is a zealot – why, he bets billions of dollars of your money on particular views of the economics of climate change, while so obscuring the choice there is no effective accountability – so no doubt there will be pages and pages of bureaucratic bumpf from an agency with no expertise in the issue (or mandate), simply adding to compliance costs (especially for small institutions).

There was a rather lame attempt to defend the Bank’s involvement in the bank conduct review. I noticed that the Governor had a bit of spat with ACT MP David Seymour at FEC last week on just this issue, which ended with the Governor (to whom any concept of deference or politeness seems unknown) responding as follows

When Seymour persisted, Orr simply said: “I am right, you are wrong”.

My own take is that they are probably both right. Seymour is right on the fundamental point – the bank conduct review was about politics and perhaps about Orr advancing his standing, not about financial soundness and efficiency (the Bank’s statutory mandate). And if Orr is correct – about the law giving him scope to do this – it is only because the legislation was written – guided by Bank officials – far too broadly in the first place.

But what bothers me rather more is the Bank’s weak understanding of the nature of financial crises, systemic risks, and so on. These are concerns I’ve raised over several years in various contexts, including the cases the Bank has made for LVR restrictions and the (longed-for) debt to income restrictions.

For example, they continue to claim that

Household sector indebtedness represents the New Zealand financial system’s single largest vulnerability.

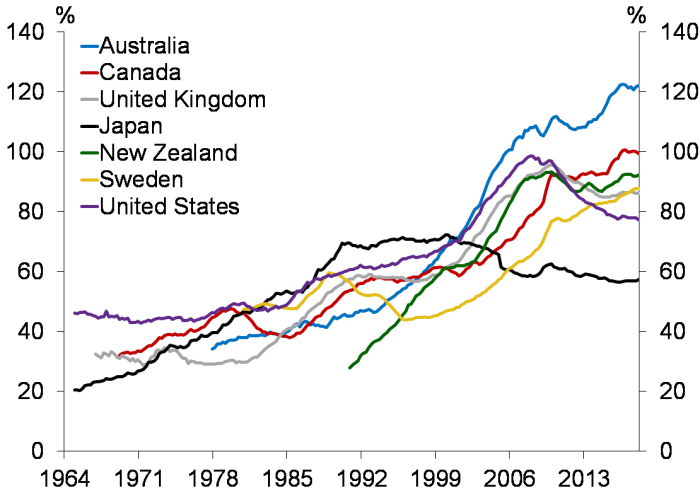

Yes, household debt is the largest component of financial system assets, but that is a quite different proposition. As their stress tests have repeatedly shown, banks’ housing portfolios are constructed in a sufficiently cautious way that even very large adverse shocks (rising unemployment and falling house prices) wouldn’t threaten the soundness of the banks. They run this cross-country chart of credit to households as a share of GDP.

Yes, there is a lot more household credit than there was. That is the inevitable consequence of things like land-use restrictions than make urban land artificially scarce (and highly-priced). And in New Zealand’s case, household debt to GDP is still a touch lower than it was going into the last recession (and at that time the servicing burden was also much heavier). Despite all the angst, bank housing portfolios came through that severe recession unscathed – as they did in Australia, Canada, and the UK.

But perhaps my biggest problem with the speech is a combination of three things:

- the attempt to suggest that the system is very fragile – at least without wise bureaucrats – and that crises are always just around the corner, coming for us,

- the continued failure to pay attention to the experiences of countries that had significant asset and credit booms and didn’t have a domestic financial crises, and

- the inexcusable failure – in a central bank – to distinguish between countries with floating exchange rates (which greatly assist adjustment in the face of shocks) and those without.

In combination, the Reserve Bank leads us towards quite misleading conclusions about the economic costs of financial crisis. By overstating those costs – hugely overstating – they seek to strengthen their own position (and our respect of them) as regulators; the people who will do everything to keep us safe. (As commonly, one never sees mentioned in the speech that in all the financial crises they like to cite, there were in fact banking regulators who no doubt thought they were doing their job well.)

Of my first bullet, they say

First, why does financial stability matter? The answer is that bank crises are frequent and bank crises hurt.

Since the mid-1970s there have been over 140 banking crises around the world.

and (without any backing for this claim)

Serious incidents (that could have led to a crisis) are more common than people realise.

Yes, there have been lots of crisis, although since (depending on your definition) there are getting on for 200 countries in the world, even the number the Bank cites is less than one crisis per country over 45 years.

But there haven’t been many at all in stable, well-managed, floating exchange rate countries. And in countries like ours – for example, New Zealand, Australia, Canada, Norway – the only financial crises in 100 years have related to the period just after liberalisation when everyone was just getting grips with what a market financial system meant (and when, for that matter, regulators also didn’t cover themselves with glory). Of course, well-run banking systems can run into trouble, but since it is New Zealand that our Reserve Bank is supposedly focused on one might expect some grounding in the Australasian experience. That experience just doesn’t suggest danger (massive credit losses) lurks continually.

The Reserve Bank has long been keen on citing the experience of Ireland as somehow relevant to New Zealand. It pops up again in this speech

The consequences in terms of employment are also severe. After the GFC, Ireland’s unemployment rate rose from 4.6 percent in 2006 to 15 per cent in 2012

And yet – prosperity and geography aside – what is the biggest relevant difference between New Zealand and Ireland? We get to set our own interest rates, and our exchange rate can adjust freely, while Irish monetary policy is set in Frankfurt for the entire euro-area, and they have no nominal exchange rate to adjust. The Reserve Bank knows very well that floating exchange rate exist in large part because they provide greater leeway to cope with severe adverse economic or financial shocks. Thus it was from the beginning – at the time of the Great Depression – and is now too. I did post a few years ago – which I can’t now see – documenting that no floating exchange rate advanced country has ever experienced an increase in its unemployment rate of the magnitude Ireland put itself through. I could commend to the Reserve Bank the experience of Iceland (which went through a financial crisis which, in many respects, was even nastier than Ireland’s, and yet had only a fairly moderate increase in its unemployment rate).

And then there is the hoary old chestnut about just how expensive financial crises supposedly are. Here is Bascand

Since the mid-1970s there have been over 140 banking crises around the world. And they have had large costs for the affected economies and societies.

On average a bank crisis costs a country 23% of its GDP, while public debt increases by around 12 percent.3 The amounts are higher for advanced economies.

That footnote records that the numbers are calculated as deviations of actual GDP from its (pre-crisis) trend.

They sound like scary numbers, and if true (in some meaningful sense) they might even be so (although even if a crisis happens every 20 years, a loss of 23 per cent of one year’s GDP is roughly a loss of 1 per cent of the total GDP over that full period). But they aren’t meaningful, on a number of accounts.

First, the calculations (implicitly) assume that any deviation from the pre-crisis trend is a result of the crisis itself – and not, for example, the misallocation of real resources that might well have occurred even if the financial system had stayed sound. At best, these numbers conflate the two effects.

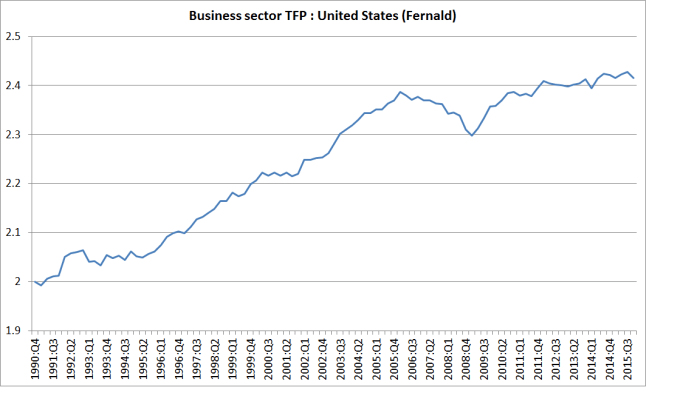

Relatedly, the estimate ignore things that might have getting underway in the year or two prior to the crisis. Thus, as I’ve shown before, productivity growth in the United States had already begun to slow very markedly a couple of years before the crisis hit.

A small amount of that might make its way into the pre-crisis trend measures, but most of it won’t.

And thirdly, the Bank – and many of their peers among other keen regulators – makes no attempt to compare the experiences of countries that went through serious financial crisis and those that did not. US economic performance over the last decade has been underwhelming to say the least. The US was at the epicentre of the 2008/09 financial crises. But it is simply a step far too far to conclude that the extent to which the US has done less well than in the previous decade is the measure of the cost of the financial crisis, especially if other countries that didn’t have a crisis also did less well than they had done the previous decade or so.

I’ve touched on this issue before, including in this post last year. Of course, finding good comparators isn’t just a matter of a random into the OECD bag of countries. For a start, as I’ve already noted (and as the Reserve Bank knows), a fixed exchange rate tends to exacerbate the severity of any shock. The United States – epicentre of the financial crisis – is a floating exchange rate country. Some floating exchange rate countries – notably the UK and Switzerland – were caught up in the 2008/09 crisis primarily because of the exposure of their internationalised banking sector to the US and its housing debt instrument (rather than because of domestic credit exposures). But there are six well-established floating exchange rate advanced countries that didn’t have a serious domestic financial crisis at all in 2008/09: New Zealand, Australia, Canada, Norway, Israel, and Japan.

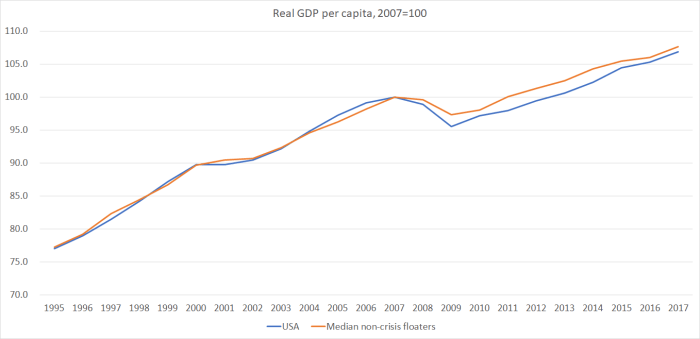

Here is how the US experience, on real GDP per capita, compares with the median of those non-crisis floating exchange rate advanced economies

The US experience was a little worse than that of the median of this group of countries, but the differences are small, and there is a lot of variability in the experience of the non-crisis countries (since 2007 Israel has done much better than the US, while Norway has done much worse). And as I noted in the earlier post, the comparison still tends to exaggerate any contribution of financial crises themselves, as the US had less fiscal leeway than all the other floaters except Japan, and the US had less monetary policy leeway (running into the lower bound) than New Zealand, Australia, and Norway.

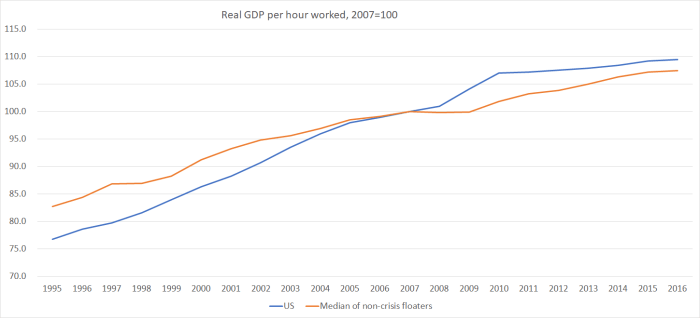

That’s GDP per capita. But what productivity? Quite a lot of the arguments about the cost of financial crises attempt to build a story about persistent dampening effects on innovation, risk-taking etc, reflected in the productivity numbers. Here is the chart, showing the same comparison countries, for real GDP per hour worked (OECD data).

Perhaps this chart is a bit more favourable to the story, depending on how you read it. Over the whole period – pre and post crisis – the US managed faster labour productivity than the median of the six non-crisis countries. But perhaps the slowdown in productivity growth is a bit more in the US than the others (even if, as the earlier chart showed more clearly) the slowdown pre-dated the crisis? Then again, the level of labour productivity in the US is higher than in all but one (Norway) of my non-crisis collection of countries, so if there was a global productivity growth slowdown (for whatever reason) you might be expect the US to be hit more visibly than the other countries (that sitll had catch-up and convergence opportunities). Even among the non-crisis countries, there is considerably divergence – since 2007 Australia has had the strongest productivity growth and Norway the weakest. (Remarkably, Iceland – savage financial crisis and all – has had faster labour productivity growth than all these countries.)

I’m not wanting to suggest that recessions and financial crises don’t have costs. At an individual level almost inevitably they do, and at a national level recessions are rarely pleasant or welcome (that’s why we have active monetary policy). But we deserve much more searching analysis from our central banks and financial regulators (and those holding them to account, including national Treasurys) when they bidding to persuade us to entrust them with so much power, and the deference due to people who make so much difference (so they claim).

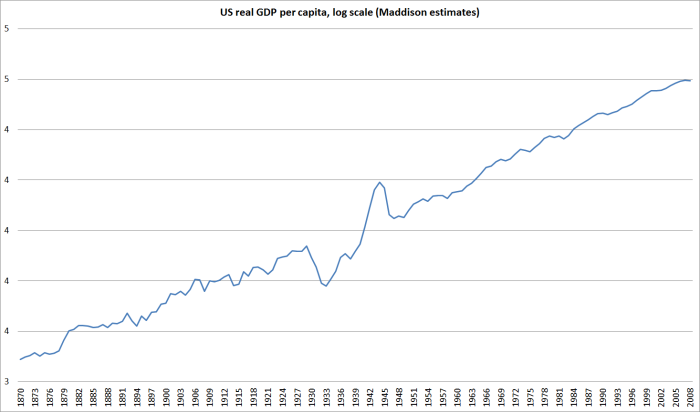

A good starting point remains this very long-term chart (due originally to Nobel laureate Robert Lucas)

As I noted in a long-ago post

It is a quite simple chart of real per capita GDP for the United States, back as far as 1870. These are Angus Maddison’s estimates, the most widely used set of (estimated) historical data, and as Maddison died a few years ago they only come as far forward as 2008. The simple observation is that a linear trend drawn through this series captures almost all of what is going on. More than perhaps any other country for which there are reasonable estimates, the United States has managed pretty steady long-term average growth rates over almost 140 years. And yet, this was a country that experienced numerous financial crises in the first half the period. Lists differ a little, but a reasonable list for the US would show crises in 1873, 1884, 1893, 1896, 1901, 1907, perhaps 1914, and 1929-33. There were far more crises than any other advanced countries experienced.

And yet, there is no sign that they permanently impaired growth, or income.

If we are to have good financial stability policy, and confidence in it, it needs to be based on good searching robust and honest analysis, that recognises the puzzles and the ambiguities in the data, not the sort that rushes to support the conclusions policymakers have already settled on.