You might have thought that there were real and important issues for The Treasury to be generating research and advice on. Things like, for example, the decades-long productivity underperformance and the associated widening gap between New Zealand and Australia. Or a housing and urban land market which renders what should be a basic – the ability to buy one’s own house – out of reach for so many New Zealanders. Or even just preparing for the next recession. Analytical capability is a scarce resource, and time used for one thing can’t be used for others.

But instead…..

In a post last night about various papers presented at the recent New Zealand Association of Economists conference, Eric Crampton alerted his readers last night to a contribution from Treasury’s chief economist (and Deputy Secretary) Tim Ng and one of his staff.

I did not attend Treasury’s session in which they noted Treasury’s diversity and inclusion programme which saw the scrubbing of the word “analysis” from Treasury’s recruitment ads as overly male-coded. Those interested in priorities at Treasury might wish to read the paper.

And so I did. I’m not sure I could recommend anyone else do so, except to shed light on what seems to have become of a once-capable rigorous high-performing institution. We’ll see later the background to the “overly male-coded” stuff, but – in fairness to Treasury – the first Treasury job advert I clicked on did still look for

- Critical thinking, analytical ability and learning agility

- An ability to drive discussion and provide critical analysis

[UPDATE: As Eric notes in a comment below, he has now amended his reference to “analysis”.]

There is no standard disclaimer on the paper, suggesting that we should take it as very much an institutional view (perhaps not surprisingly, when one of the authors is a member of the senior management of The Treasury).

The Ng/Morrissey paper has several sections. The first relates to what the authors describe as “women’s (in)visibility within mainstream economic theoretical approaches, in particular, with respect to the conception of ‘rational man’.

A well-known trope in economics (and in critiques of economics and of economists) is that of the rational individual, one who is self-interested and seeks to maximise their own welfare, and who is consistently rational in the sense of diligently and correctly applying the calculus of constrained optimisation using complete information. Sometimes this actor is explicitly referred to as a man (especially in writings earlier than the mid-20th century – no doubt at least partly reflecting the linguistic conventions of the time). At other times, it has been argued that this is implicit in the way in which the scope of the subject is defined for the purposes of research or pedagogy.

In my years of formal economics study – some decades ago now – I don’t recall any aspect of economic analysis ever being framed in terms that focused on men, or male involvement in the market. Since I focused mainly on macroeconomic and monetary areas, perhaps it was different in other sub-disciplines, but I doubt it. And if standard simplifying assumptions – as much about tractability as anything – about rationality are a common feature in models, those assumptions are not, actively or implicitly, focused on male perspectives. They are a proposition that people will use the information they have, that they will pursue the best interests of themselves, their families, or other things they care about. None of which should be terribly controversial.

But Ng and Morrissey seem to think something terribly important is missing.

We look at the degree to which mainstream theory adequately captures the value of the roles typically undertaken by women, especially unpaid care work, and examines how alternative models, such as those based on the mother/child relationship, could improve economic understanding and policy advice in contemporary developed economies.

They go on

There is a consensus from a number of notable authors that the new paradigm would have the mother / child relationship at its heart as this provides a more accurate depiction of fundamental human interaction.

Both Orloff (2009) and Strassman (1993) identified human’s dependency in infancy and old age, and often in between, as unchosen but present. By identifying dependency as natural they resist the negativity now associated with the term. Folbre (1991) considers how this negativity came about and suggests that women’s dependency was created as a fact through discourse, in the vocabulary used in the political and economic census, which tied non-earning women to earning or moneyed males.

Held (1990) makes her case by identifying the inherent dependency within the relationship between the mothering person and the child, and based on her observation of children as ‘necessarily dependent’, she puts this need at the centre of human interaction. Hartsock (1983) makes a similar argument in asserting mother/ infant as the prototypical human interaction. The importance of this relationship is discussed by Fineman (1995) who suggests the classic economic focus on the sexual relationship neuters the mother from her child.

I struggle to see how any this – even if it has any substantive merit – has any relevance to the sort of work, and advice, The Treasury should be providing. But no doubt it goes down well with the Ministry for Women.

The authors do offer some thoughts on the potential relevance. They begin thus

The implications of the above for policy depend to some extent on the degree to which gender roles and preferences are socially constructed (rather than innate). If the latter, then policy settings (e.g. labour market regulation) have a role not only in recognising different gender roles and preferences, but also in possibly reinforcing or leaning against gender roles that contribute to gender inequality. A more comprehensive microeconomic and measurement approach that incorporates care work would support better analysis of policy settings to promote better gender equality over the longer run.

But even this is almost content-free. Whether things are socially constructed (society having evolved the way it did for reasons that presumably had survival value) or innate, what role is it of The Treasury to be trying to impose its vision on how people organise their lives? What, after all, does “gender equality” mean – beyond individual equality of opportunity, before the law – if there are indeed innate differences (on average) between men and women?

It is a very heavy-handed feminist analysis

A number of feminist theorists have noted the value of paid employment for women. It has been suggested as being ‘constitutive of citizenship, community, and even personal identity’ (Schultz, 2000:1886). It has also been proposed to be a vehicle for participation in society and entitlement to social insurance rights (Lister, 2002:521). Of course paid work also has benefit to women in terms of poverty alleviation (Lawton and Thompson, 2013; Ben-Galim et al, 2014; Thompson and Ben-Galim, 2014).

Whereas I’m quite sure my grandmothers (and even my mother) would not have seen paid employment as a positive for them (or for their families). Both would have seen it as constraining their ability to be heavily involved in church and community activities. Nor, in today’s terms, is there any recognition of the fact that many families would prefer one parent (often the mother) to be able to stay at home fulltime with young children, but find that a near-impossible choice to make given the dysfunction that is the housing market. (And, as a voluntary stay-at-home parent – albeit male – I don’t feel remotely disenfranchised or devalued as a result of that household choice.)

Four pages of the paper is devoted to a rather strained attempt to demonstrate the potential value of a gendered lens on macroeconomics (Ng is a macroeconomist, indeed a former Reserve Bank colleague of mine). Some charts show basically no difference between the cyclical behaviour of male and female unemployment rates, but the authors are undeterred

Of course, this descriptive commentary is just that – we are not attempting here to make strong empirical claims about gender differences relevant to the cyclical labour market behaviour. Instead the idea is to simply to illustrate, with a bit of introspection, the directions in which policy thinking – macroeconomic in this case – could be enriched if a gender lens is taken, exploring the possible links between behaviour within the household regarding participating in the labour market vs. other activities, and the possibly gendered impacts of macroeconomic phenomena on employment, which is an important contextual factor for within-household decisions. A public policy which aspires to be relevant to different groups in society, including different genders, and cognisant of the possibly different impacts of policy on those groups, could be strengthened by taking more of this kind of approach.

For all the blather – and without denying that it can be interesting to understand differences in how different population groups (male and female, old and young, European and Maori, Christian, Muslim, Hindu, and pagan, and so on) behave – there is, it seems, nothing there.

Having failed to demonstrate a problem – except perhaps an agenda to pursue – the authors push on to look at the participation of women in the economics discipline. This. it appears, is key (to what, one might ask?)

Education is our critical starting point. Those who study economics will later be those who practise economics, those who work in policy making, and those who undertake economic research. In order to ensure diverse perspectives are represented within that work, particularly with respect to gender and other distributional consequences of economic policy, it is important to have diversity within those who study economics. As this paper specifically focuses on gender, we will consider the position of women in economic education, in particular. Such a focus is supported by New Zealand’s international obligations through the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

When authors have to invoke CEDAW (twice in two paragraphs) and UN SDGs you know they are on substantively weak ground.

As the authors demonstrate, numbers of people studying economics have been in decline (not just in New Zealand). That probably should be of concern, at least to agencies wanting to employ economists. The authors present numbers suggesting that, at least at high school level, the drop has been particularly concentrated among girls (personally – and I have both a son and a daughter doing high school economics at present – that seems a wise choice on the girls’ part, so mind-numbing (and non-economic) is much of what is taught as economics at high school).

At an advanced tertiary level, it seems that perhaps a third of the economics students are female (in 2014, 31.4 per cent of economics doctorates were awarded to women). Ng and Morrissey don’t like this at all.

What is our impressionistic conclusion about these patterns in participation in economics education by gender? There appears to be a “pipeline” problem with both genders, and some evidence that the proportion of women is falling – a double whammy in terms of the female economist pipeline in particular. Evidence is accumulating on a number of smoking guns relating to the way in which economics itself is taught and perceived, how leaders in the field are presented, and questions about the social construction of our identity as economists. It appears that a lot of work is needed on several fronts to improve the female pipeline into the profession.

But what, specifically, is the problem? They don’t say? Do they have a problem with the fact that 97.5 per cent of speech langugage pathologists are women or that 98.3 per cent of automotive service technicians and mechanics are male (US data for 2016)? Can they, for example, point to areas where The Treasury’s analysis and advice has been deficient because female students have chosen – and over decades now it has been pure choice – not to study economics? They make no effort to do so in the paper. The consistent undertone appears to be that Treasury (and economists) make policy, when in fact politicians make the big choices (and, as it happens, in New Zealand three of our last five Prime Ministers have been female).

Ng and Morrissey go on to a new section of the paper

This section reports some experience with a programme to increase gender diversity in an economic and financial Ministry, the New Zealand Treasury.

They perhaps don’t help their case by suggesting that the current head of the International Monetary Fund is an economist, when in fact she is a lawyer and politician.

Treasury is certainly at the forefront of politically-correct blather

In the context of the now well-established literature on the benefits of diversity for the quality of decision making, as well as an obligation to be a good employer, the Treasury has for some time had an active and comprehensive diversity and inclusion (D&I) programme. The discussion in Section 2 about the (non-)role of women in mainstream economic models and approaches, and the consequences of the potential “blind spots” this might imply for policy development, reinforces the importance of gender diversity in a Ministry focused on economics and finance such as the Treasury. Meanwhile, the gender imbalance in the economist pipeline discussed in Section 3 underlines why the Treasury cannot be complacent about this issue.

In fact, this stuff carries over to the Treasury Annual Report

The Secretary to the Treasury co-leads the diversity and inclusion work stream in Better Public Services 2.0 and is a Diversity Champion for the Global Women’s Champions for Change initiative.

Too bad he isn’t a champion of analytical excellence, or of fixing New Zealand’s deep-seated economic problems (but then, not being a New Zealander, he doesn’t have much motivation to care).

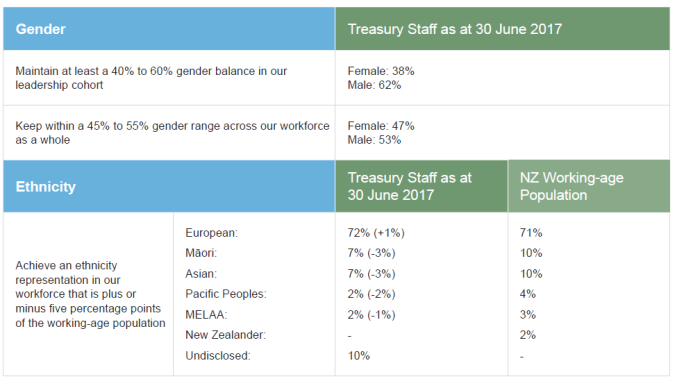

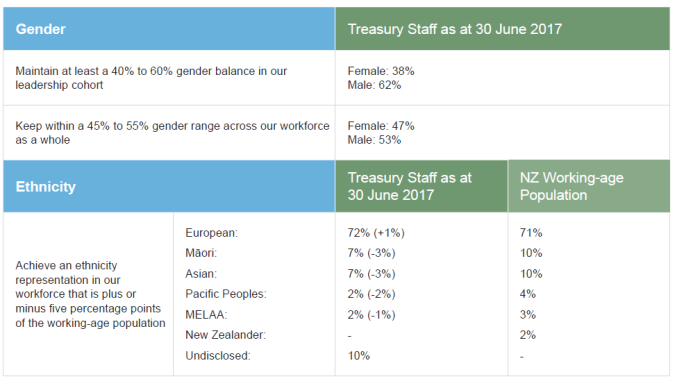

Consistent with all this, they run quasi-quotas. They would probably object to the numbers being called quotas, but when you report your target near the front of your Annual Report, it must put a great deal of pressure on individual managers to hire to the quota, not to ability to do the job.

Franly, citizens should be more worried about the proportions of people who are top-notch economic and policy analysts, not their skin colour or sex.

But not, apparently, at Treasury. Here is Ng and Morrissey again

As the data above suggest, a clear issue is the lack of women in senior leadership positions, and part of the response includes obligations on managers to have regular career discussions with all staff on a regular basis and for succession planning to more systematically address possible sources of disadvantage for women. Within-grade gender pay gaps are regularly examined and the target of eliminating any such gaps explicitly included as a criterion in annual remuneration reviews. The parental leave and flexible working policies are regularly reviewed to check for gendered impacts.

But still with no attempt whatever to suggest how any of this has adversely affected Treasury’s policy advice. Surely that should be the most important test?

It is also clear that The Treasury is dead-keen on the flawed concept of unconscious bias (here for some problems with the Australian public service experience), and the associated training/indoctrination.

Application of emerging insights from studies of unconscious bias have been quite influential in this work, and point to certain interventions and relatively simple changes in HR processes that may help to address some of these biases. For this paper, we took the opportunity to explore in some detail the Treasury’s recent use of a tool, Kat Matfield’s Gender Decoder, which provides an easy way of assessing the potentially different impacts on prospective male and female applicants of language used in job advertisements. The Treasury now has about two years of experience with using this tool as a way of reducing unintended gendered impacts on pools of job applicants

What of this tool?

The Gender Decoder is available on the web at http://gender-decoder.katmatfield.com/. This tool is based on the findings of Gaucher et al. (2011) which provide evidence that certain words in job ads appeal differently to each gender, which may be a channel to exacerbate existing gender imbalances by profession, especially in traditionally male-dominated occupations. The theoretical mechanism is essentially that words connoting individualism and agency (“leadership”, “ambitious”, “challenging”), or that reflect stereotyped male traits, tend to appeal more to male applicants, while words connoting communalism or that reflect stereotyped female traits appeal more to female applicants.

They attempt some analysis of Treasury’s experience with the tool (emphasis added)

To look at gendered language in Treasury job ads in general and the possible impact of the use of this tool, we sampled 40 job ads posted by male and female hiring managers, 20 before and 20 after the introduction of the use of the tool in March 2016 as a recommended practice in Treasury recruitment.

Looking at the pre-2016 ads, it is notable that male and female hiring managers tended to code their ads towards their own gender, with male managers in particular tending to use strongly “masculine” language. Post 2016, male managers showed roughly balanced gender coding in their ads, while female managers showed a dominance of masculine-coded ads. The preponderance of strong gender coding increased after the introduction of the use of the tool, the opposite to what one would expect if the tool alerted managers to unintended or unnecessary gendered language in ads and if the managers wanted to attract gender-balanced pools of applicants (as they are encouraged to do by Treasury policy).

So those were “quotas” again, in that final sentence? I’d hope Treasury managers, male and female, wanted the best pool of applicants, based on ability to do the job, not based on some institutional gender quota approach (that seems to disregard the fact – demonstrated earlier in the paper – that at least among economists, there will only be half as many women as men in the overall pool to atract applications from).

The authors reflect

Faced with this somewhat surprising result…..we looked at the nature of the jobs advertised themselves, and this exercise suggested to us some limits to the effect that scrubbing job ads of unintended gendered language can have on the gender split of applicants, including for economics jobs. The masculine-coded ads tended to be for jobs in the analytical functions of the Treasury, and “analysis” is coded as a masculine word by the Gender Decoder. Treasury also routinely presents itself as “ambitious” and a “leader” – another masculine-coded word – in the area of economic policy. The feminine-coded ads tended to be for “support” and corporate jobs, with an emphasis on “collaboration” – both feminine-coded words.

Dear, oh dear. Treasury management has for some time been using an HR tool that treats “analysis” as some nasty male word. Perhaps this paragraph should lead Ng and his senior management colleagues to rethink, and to wonder whether zeal and ideological presuppositions have not been not been outstripping evidence and analysis?

The Ng and Morrissey paper concludes this way

This paper has reviewed the position of women in economic theory, economics education and economics practice. We argued that the role of women and care work is insufficiently incorporated into mainstream economic models and approaches, and illustrated how a more gender-sensitive approach could enrich a particularly gender-blind sub-discipline – macroeconomics. We then documented the lack of a deep pipeline of women entering the profession, and the gender imbalance at senior levels in our own economic Ministry.

and

We conclude that the position of women in all three areas of economics is unsatisfactory. While the quality of management and decision making in general has been shown to benefit from diversity in general, in the delivery of quality economic policy advice that benefits all New Zealanders, it is particularly important that a diversity of perspectives is represented.

As a profession we have lots of work to do.

Eric Crampton has previously challenged as “wishful thinking” (or worse) the Secretary to the Treasury’s repeated insistence on the substantive benefits from “diversity” (population diversity, rather than diversity of view). Other recent New Zealand research has challenged that proposition too.

The Treasury seems to have become committed to the modish view that how one analyses an issue depends on where one comes from (at least race and sex, although presumably their logic applies to age, religion, birthplace, and all the other trendy identity markers). As an institution, they now have a huge distance to go, lots of work to do, to restore a reputation for analytical excellence. Between their institutional weaknesses and the lack of demand for excellence from our politicians, it is no wonder our serious economic problems aren’t seriously addressed. Pursuing modish causes, no doubt ones in favour with the government of the day, is easier I guess.

The former Minister of Finance, Bill English, had many weak points in his political record. Among them was his decision a few years ago to support the reappointment of Gabs Makhlouf as Secretary to the Treasury (when, within the law, he’d have been quite within his rights to have asked SSC to find someone who might actually restore the quality of Treasury we once had). We are the poorer for that degradation of what was once a strong, robust, and analytically-driven institution. Politicians make policy, and a good Treasury can’t force them to make good policy, but a poor Treasury gives them all the excuses they need to avoid tackling the real issues (while revelling in the feel-good content-lite nature of the coming Wellbeing Budget).

In the meantime, one has to wonder about the opportunity cost of the Ng/Morrissey paper. Time spent writing it, is (taxpayers’) time that could have been used for tackling some real issues.