When I stopped regular blogging in December I wrote

This is one of those issues that has really got my goat. (There won’t be any other return to blogging, although if I make a submission to the government’s belated independent review of Covid-era monetary policy I might put a link to that in a post.)

It is a nice summer evening in Wellington and would be a good time to be at the beach but….well…Wellington City Council…

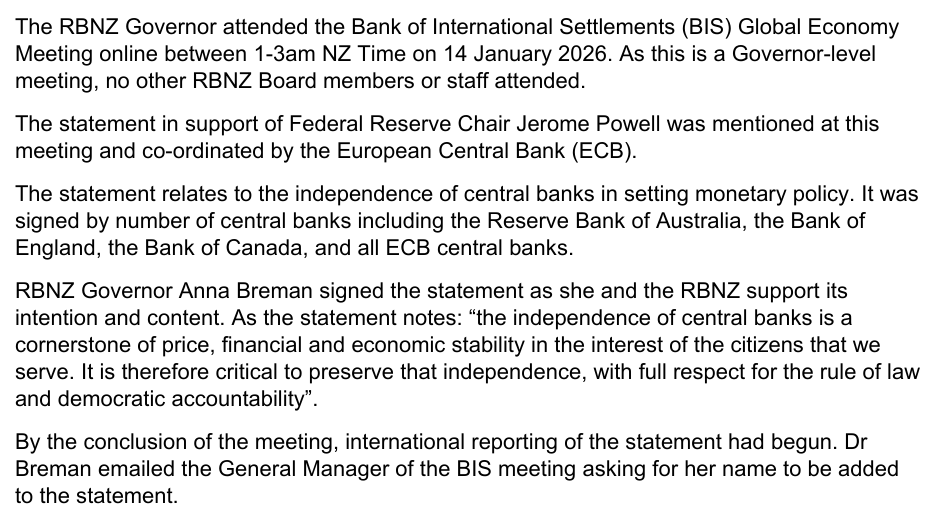

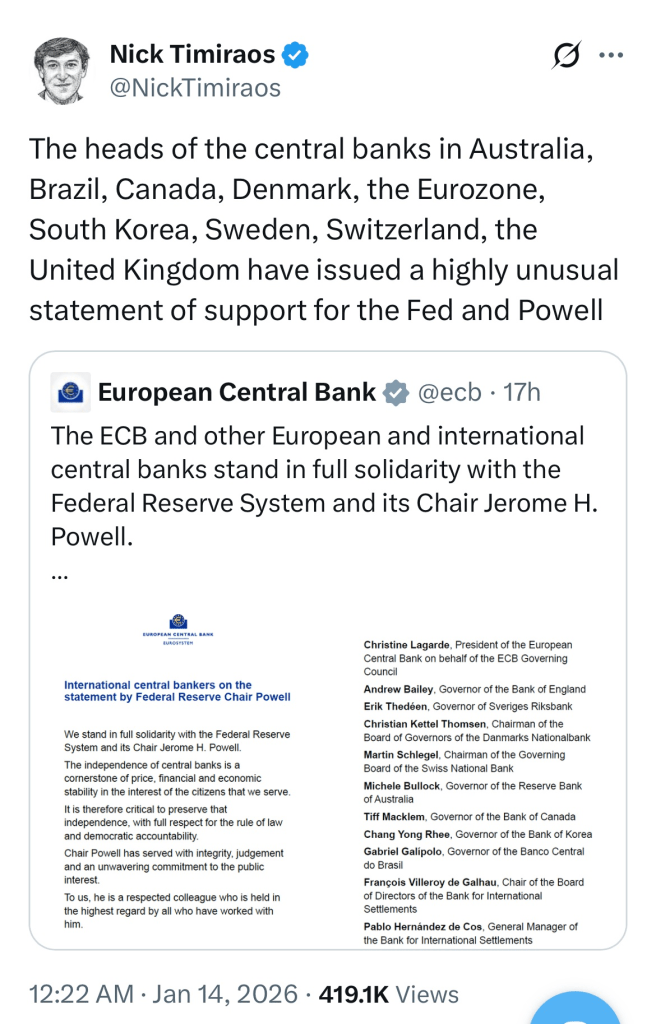

A month or so ago the new Governor of the Reserve Bank signed up to a public statement by a group of several other central banks (ECB, BOE, RBA, Riksbank etc) in support of the outgoing Fed chair, Jerome Powell, following his revelations of what appeared to be an attempt to intimidate him by Trump’s Department of Justice. Most of the world’s (operationally independent) central banks didn’t sign (14 central banks signed up, and among those who didn’t were – from among advanced countries – central banks of Japan, Israel, Czech Republic, Poland, and Chile). Nor, of course, did the non-independent central banks from advanced countries (Singapore, Taiwan).

One can debate the substantive pros and cons of the statement (eg was it wise, helpful, accurate and so on). But that isn’t my focus here. One can also debate the best way for countries to respond to Trump (my own stance would be much more openly critical than our government’s own timid approach). But again not my focus here.

Instead my focus is on the Reserve Bank Governor’s approach and response.

Shortly after the news emerged that she had signed on to the statement (on 14 January) I OIA’ed the Bank (and the Minister) for all relevant material, including on (for example) invitations to join, consultation within the Bank, and consultation across other government agencies/ministers. An hour or two later, the Minister of Foreign Affairs Winston Peters had a go at Breman, noting that there had been no consultation with MFAT and strongly suggesting that the Governor needed to stay in her lane, suggesting that the Bank had operational independence in various domestic areas, but not to go trespassing across foreign policy, as a government agency.

(Personally, my initial scepticism about signing had to do with the credibility of the Reserve Bank itself – if you wanted good central bank governance and accountability you would certainly not have looked to the Reserve Bank of New Zealand over the last couple of years (budget busting, active misrepresentation by the outgoing board chair, repeated attempts to mislead Parliament, and finally the appointment of a new chair who’d been not only an active part of all that but had initially been appointed to the board when he had a clear conflict of interest. Oh, and a Minister of Finance who prevailed on the Bank to change its – independent – bank capital policies. Should anyone in the US administration have cared enough, a New Zealand signature would have looked laughably hypocritical (even if the new Governor might have good intentions.)

As it happens, in this particular saga documents released today suggest that, for all his other faults, the Board chair was one of the adults in the room.

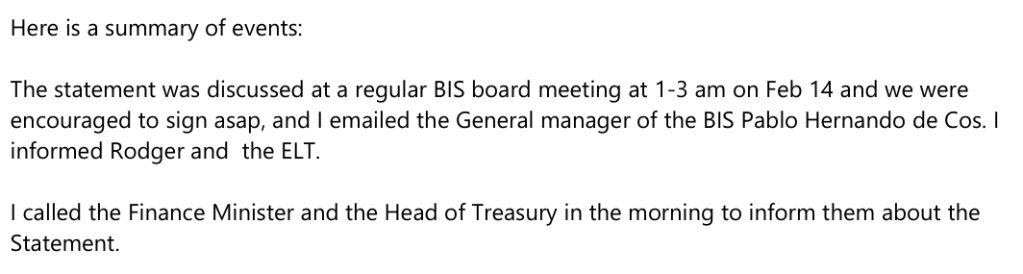

You may recall that the Governor claimed that she was under real time pressure to sign up to the statement (at an on-line BIS meeting held from 1 to 3am that day). And, being the middle of the night, she didn’t feel she should bother the Minister of Finance (for example). The Minister of Finance has since made it pretty clear that the Governor should have felt free to have rung. The Prime Minister also weighed in with a gentle rap over the knuckles. And the Governor has apologised to both ministers (Finance and Foreign Affairs) for having gone ahead without consulting them (and/or their agencies).

When you listen to the Governor’s rhetoric one of the attractive dimensions is the claim that she wants a greater degree of transparency. That is welcome, but once again she does not walk the talk.

That OIA request of mine was lodged on 14 January. The Official Information Act requires agencies to respond as soon as reasonably practicable. The deadline for my request is tomorrow (the Bank probably envisaged sending it at 5pm on Friday). But this afternoon a 39 page release appeared silently (no press release or anything) on the pro-active releases page. I happened to spot it only because I was checking up something else. The 39 page document is presumably what they will tomorrow treat as the response to my OIA. Were they actually committed to transparency they could have put the lot out just a few days after the request was received (the release consists of a summary statement, a long set of letters from members of the public in support or opposed to the Governor’s decision to sign up, and a set of emails mostly among a few senior managers and board members, with no substantive redactions). But when bureaucrats tell you they are committed to transparency, mostly it is only for occasions when it suits them, and that is no accountability at all.

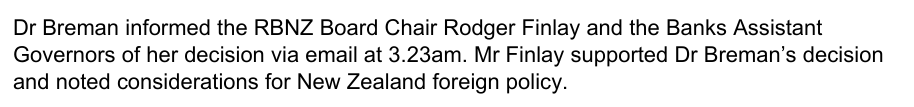

I’ll use the “Summary background statement” to frame all that follows, since it is the story the Governor has apparently chosen now to tell.

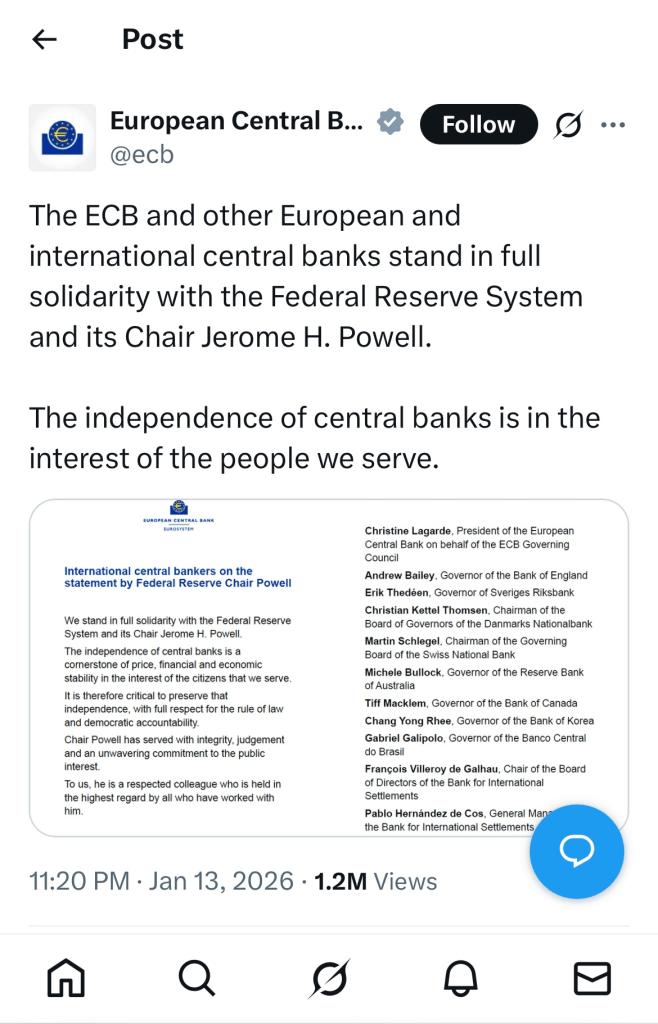

Which is fine, except all that it leaves out. What you would not know from this statement, or any comment from the Bank last month, is that the initial statement (9 central banks signing) had gone out a couple of hours before the BIS meeting (at 11:10pm New Zealand time). The ECB had it on its Twitter feed by 11:20pm

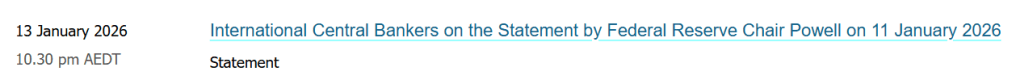

And, despite the Governor’s comment that “by the conclusion of the meeting, international reporting of the statement had begun”, in fact the WSJ’s chief economics correspondent had been tweeting about it by 12:22am

In this part of the world, the RBA had put the statement on its website at 12:30am NZ time

The statement had gone out, and was being reported on, before the 1am meeting even began.

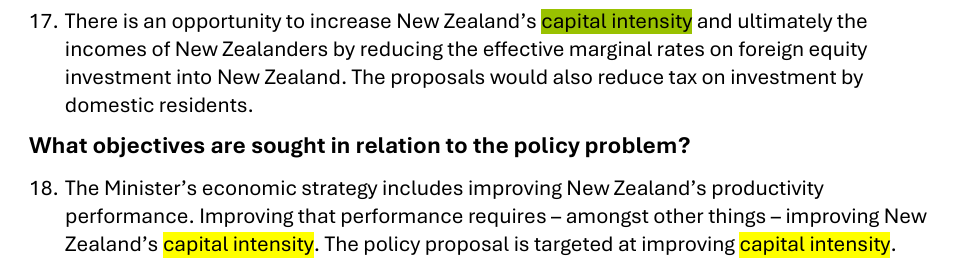

There is no sign that the Governor or her staff were aware of any of this or (importantly) that they had even been invited to sign. My OIA request included any invitations to sign or correspondence with other central banks etc, and there is simply nothing of that sort in the response. The nine signatories will not have done so on the spur of the moment (there must have been exchanges over drafting, substance etc in at least the day prior to release, and probably at least some heads-ups within those individual central banks and perhaps to other government agencies/ministers. Some who were invited – one might guess the BoJ – apparently chose not to sign.)

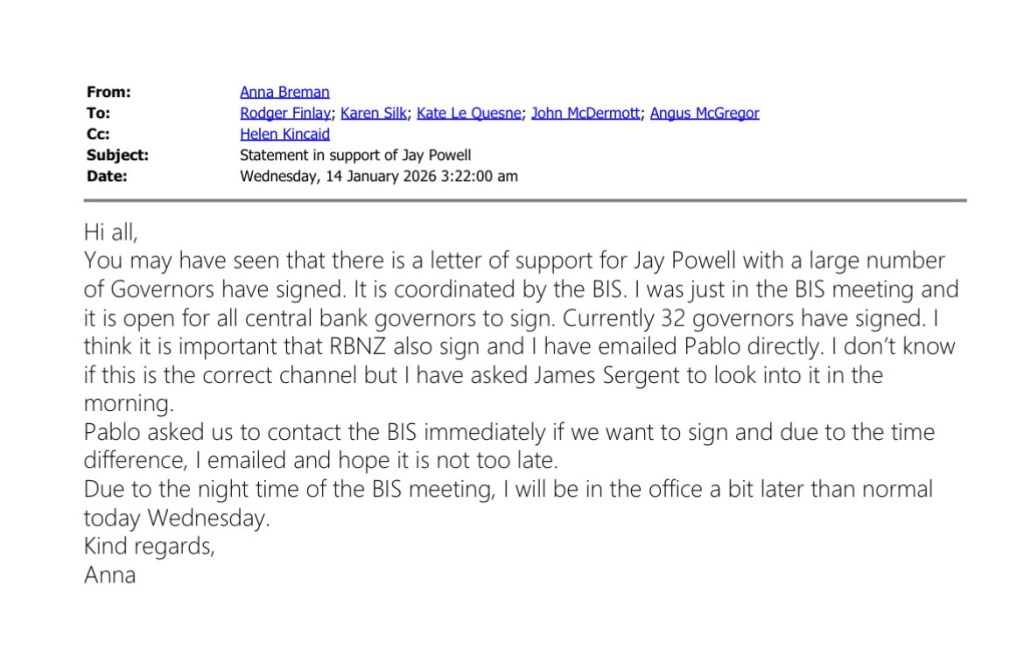

Apparently (from the Governor’s email to her staff at 3:23 that morning) in the BIS meeting it had been indicated that any central bank that wanted to was free to sign. The Governor notes that “I..hope it is not too late” for them.

There is simply no basis for her claim that there was anything so pressing she needed to act immediately. The statement had gone out already, she hadn’t been invited….but perhaps she wanted to associate with the “cool kids” central banking club? Why would she still be seeking to mislead the public like that?

What of consultation?

It turns out that she consulted no one at all. Not senior staff, not the Board chair, not the ministers, not the Treasury or MFAT. We’d been told previously that she had informed Finlay. It wasn’t then clear whether that was before or after she signed (bearing in mind it was the middle of the night there may have been no practical difference if she’d just sent an email).

Here is the email, sent nine minutes after her email signing up.

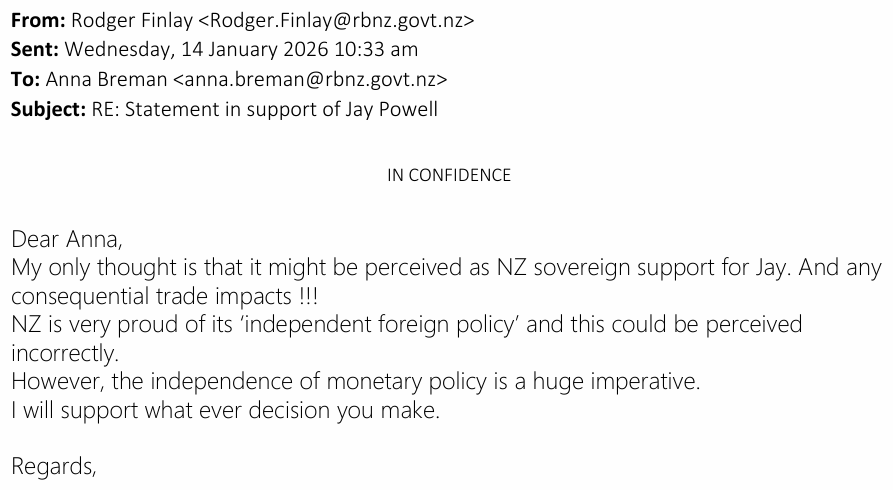

Quite a few hours later the board chair Finlay gets back to her

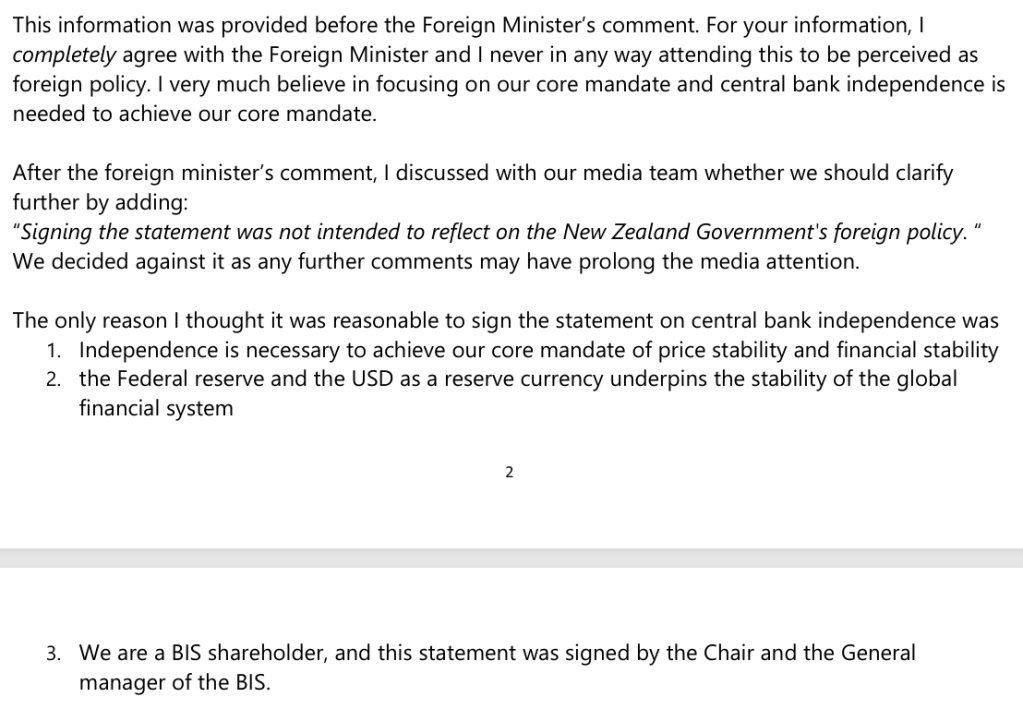

You can tell he is not exactly impressed and, again, the Governor’s statement spins things in her favour. He raises the foreign policy concern issues – exactly of the sort the Foreign Minister would later make in public. And while Breman is technically correct to say that “he supported her decision” it really reads a lot more like “what is done is done. too late now, but….you are my new handpicked Governor and of course I will back you”.

That he was hardly an enthusiastic supporter is also implied by a email to the Board the Governor sends out the following day, which includes this “I have discussed this with our Chair at length yesterday”. The “at length” really says it all. Finlay seems to deserve a rare “well done”.

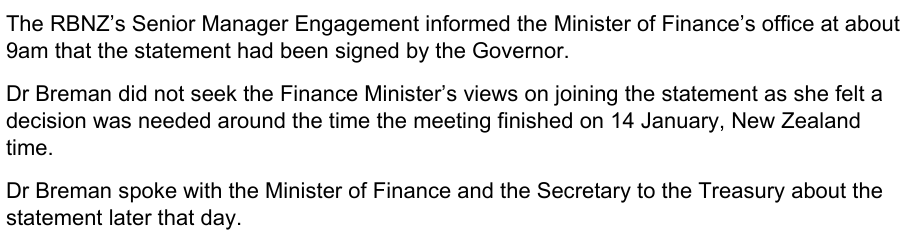

And what of the rest of government. The official statement now says:

But in fact, even here the documents released suggest a less favourable story. Two of the Assistant Governors weigh in enthusiastically when they finally read the email (after 8am – don’t these senior people check their emails when they wake up?), only for one – a non policy guy – to suggest that perhaps “we should also give MoF a heads-up…..maybe MFAT” – maybe, when the boss has, hours ago, signed up to a statement by implication attacking the volatile US President. Karen Silk, the egregiously underqualified macro policy DCE then qualifies her enthusiasm with a belated “sorry, also agree with John – in particular MFAT just as an FYI”. She – the macro person – apparently didn’t think Treasury or the Minister were worth bothering about.

The Governor herself may still have been on her way to work at this point – she isn’t part of the email chain – but some comms people get on to telling the Minister of Finance’s office, but even then there is no record of them advising Treasury or MFAT. Quite when Breman spoke to Willis or Rennie isn’t clear although it seems to have been later in the morning (there is no email traffic relevant to these calls, either mooting them or reporting what was discussed).

The final set of documents released relate to an email to Board members from the Governor the following day.

She claims “we were encouraged to sign asap” but…..after all, she was a free agent. The statement itself had already gone out. It is simply extraordinary that the Governor – a new Governor, with probably (and understandably) little sense of New Zealand government ways or foreign policy perspectives – allowed herself to be rushed into signing up with the cool kids without consulting a single other person on her side, in the middle of the night. What, precisely, would have been the consequences of having said “it is the middle of the night here, I’ll talk to my colleagues in the Bank and elsewhere in government and get back to you by midday”? (In fact the statement on the ECB website still reads “Other central banks may be added to the list of signatories later on” although none have been added since later that first day.)

She concludes this email to board members this way

It betrays an almost incredible degree of naivete. The Bank – like many government entities – has some, quite defined, operational independence. It is however fully a part of the New Zealand public sector. The Minister of Finance appoints and dismisses the Governor, sets spending limits, sets policy targets etc. How did the Governor not think that her signing on might be seen by some as stepping across foreign policy boundaries? Being the middle of the night is no excuse – all manner of real crises can occur in the dark hours too. It was a serious rookie error.

Responses from only two board members are recorded, both formal and neither offering either support (or criticism)

And the Bank’s summary statement ends this way

Previous reports indicate that she had also apologised to the Minister of Finance.

As I said earlier, I’m not here to debate the pros and cons of the statement. My interest is in two things. The first is the apparent inexperience and rookie-error stuff of the new Governor, revealed in her actions and descriptions. Relatedly is how weak her management team seem – it took hours for any one of her top team to suggest that perhaps they needed to look others in government know, none of them raised the foreign policy/appearance issues, and none of them seem to have proposed a strategy to deal with the mess they found when they woke up (Silk, here, seems particularly culpable).

And then there is the spin still to this day. Why skip over the fact that you hadn’t been invited to sign up initially, or that the statement had gone out (and been reported on) well before the 1am meeting even started. Why suggest, in the summary statement, that the board chair had been more enthusiastic than the later documents really suggest. Why imply an urgency – to act without consulting anyone, having gone into a meeting apparently not even aware of the statement – that simply was not, in any substantive way there.

It is a pretty poor start from the Governor, not at all consistent with her statements about improving transparency. Perhaps it is an illustration of the old line that you can change the people but organisational cultures – good and (in this case) ill – can prove quite enduring.

She needs to up her game, and the board and Minister need to insist on it.

UPDATE (Fri): The OIA response came this morning (in substance the same as what the RB put out yesterday)