Tyler Cowen had an interesting and thoughtful piece on Marginal Revolution yesterday, headed Why Brexit happened and what it means. He summarises his answer as “ultimately the vote was about preserving the English nation” – on this telling, primarily about immigration. And despite his own pro-immigration inclinations, he runs a sympathetic interpretation of why a majority of British voters might reasonably have voted as they did.

He runs a story in which there is something distinctly different about Britain (along with Japan and Denmark)

One way to understand the English vote is to compare it to other areas, especially with regard to immigration. If you read Frank Fukuyama, he correctly portrays Japan and Denmark, as, along with England, being the two other truly developed, mature nation states in earlier times, well before the Industrial Revolution. And what do we see about these countries? Relative to their other demographics, they are especially opposed to very high levels of immigration. England, in a sense, was the region “out on a limb,” when it comes to taking in foreigners, and now it has decided to pull back and be more like Denmark and Japan.

The regularity here is that the coherent, longstanding nation states are most protective of their core identities. Should that come as a huge surprise? The contrast with Belgium, where I am writing this, is noteworthy. The actual practical problems with immigration are much greater here in Brussels, but the country is much further from “doing anything about it,” whether prudently or not, and indeed to this day Belgium is not actually a mature nation-state and it may splinter yet. That England did something is one reflection of the fact that England is a better-run region than Belgium, even if you feel as I do that the vote was a big mistake.

I’m not sure I’m totally persuaded by the idea that immigration was the main factor explaining the British vote. One of a package of issues no doubt, but whether it is the main story is another question. After all, Lord Ashcroft’s poll asked thousands of people why they had voted as they did. Here were the results

-

Nearly half (49%) of leave voters said the biggest single reason for wanting to leave the EU was “the principle that decisions about the UK should be taken in the UK”. One third (33%) said the main reason was that leaving “offered the best chance for the UK to regain control over immigration and its own borders.” Just over one in eight (13%) said remaining would mean having no choice “about how the EU expanded its membership or its powers in the years ahead.” Only just over one in twenty (6%) said their main reason was that “when it comes to trade and the economy, the UK would benefit more from being outside the EU than from being part of it.”

Among both Labour or Tory voters the biggest single reason for voting Leave was, on respondents’ own accounts, “the principle that decisions about the UK should be taken in the UK”. If governments are going to do something as silly as ban powerful vacuum cleaners, at least it should be our own government that does it.

Perhaps voters were reluctant to own up to concerns about immigration as the most important factor? And perhaps immigration and the changing character of the country was important beneath the surface – as the economic underperformance of the last nine years has probably been. But it isn’t an open and shut case that this was mostly an immigration referendum. After all, stories – accurate or not – about the EU wanting to ban bendy bananas, or force people to use metric units, have had considerable traction in Britain for decades.

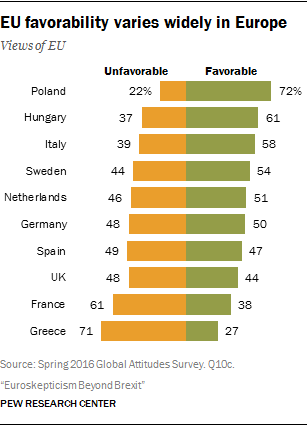

And if you were British you might reasonably think you would be at least as well off having your own government makes the choices for you. Things might seem different in the rest of Europe where, for example,

- in 1970, Spain, Portugal and Greece were under authoritarian dictatorships,

- in 1980, the Baltic states didn’t exist as recognized entities, and Poland, Rumania. Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, Croatia and Hungary were all under failing Communist rule (and four of those countries didn’t even exist independently),

- Finland Ireland, and Norway (the latter not in the EU, only the EEA) weren’t independent countries as recently as 1900,

- Germany had its unsavoury 20th century history (accompanied by Austrians cheering for the Anschluss),

- Denmark, Belgium, Netherlands and Luxembourg were all occupied by Germany for several years,

- Having been defeated by Germany in 1871, and narrowly (and at vast cost) winning World War One, France then endured the shame of German occupation in World War Two, the collaborationist Vichy regime, and the crisis of 1958,

- Malta’s 40 years between independence and joining the EU was the historically abnormal self-rule phase.

It doesn’t leave many countries where citizens can look back over the last 150 years and say “yep, we ran ourselves over long periods of time pretty well really”. But Britain did. Now, as we know, there is plenty of anti-EU sentiment in much of the rest of Europe as well, but it seems quite readily understandable, just in terms of their own country’s history, that UK voters would prefer their own governments to make decisions for them. And it doesn’t take a huge political and bureaucratic edifice to establish a free trade area, or a mutual external defence arrangement (such as NATO).

Having said all that, what really prompted me to write this post was this line in Cowen’s post.

Of course, USA and Canada and a few others are mature nation states based on the very idea of immigration, so they do not face the same dilemma that England does. By the way, the most English of the colonies — New Zealand — has never been quite as welcoming of foreign immigrants, compared to say Australia.

I’m at a loss to know what he is basing that final sentence on. For better or worse – and given the economic opportunities here, I think it has been mostly for the worse – that proposition seems to be defied by the data.

At times, I’ve had people run the line to me that since in 1500 the non-indigenous populations of New Zealand, Australia, Canada and the United States were all, essentially, zero, and since New Zealand has by far the smallest population of any of those countries we must have been less open to immigration. But those other places started European settlement and immigration earlier than we did – and were closer to Europe, at times when travel costs (mostly elapsed time) mattered hugely.

I’m going to start my comparisons from 1870. That is partly because I was using the Maddison database and its first annual New Zealand population numbers are for 1870. But it also seems reasonable on other grounds. In both New Zealand and Australia the influxes (and outflows) associated with the respective gold rushes were over by then, and by 1870 the New Zealand Land Wars were winding down – never thereafter was there any serious question about settler control of the North Island. The large scale Vogel immigration and public works programme began shortly thereafter.

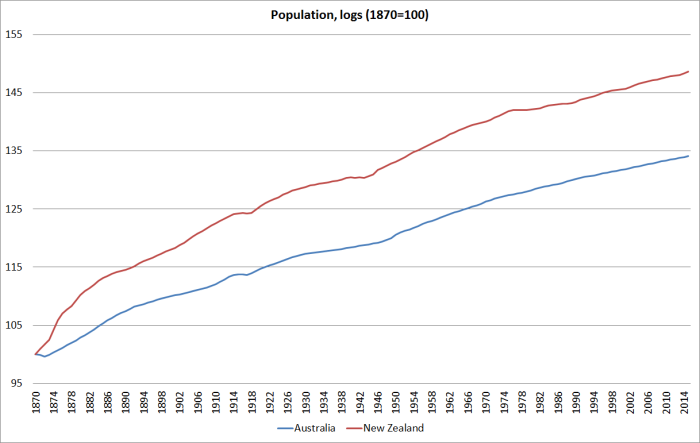

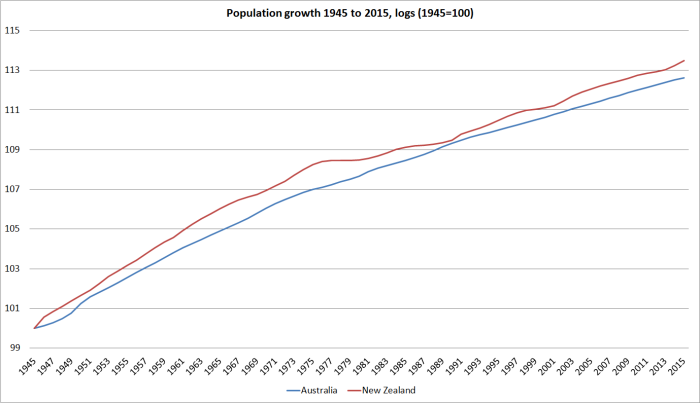

Here is a chart showing the total populations of New Zealand and Australia since 1870, both normalized to 100 in 1870, and done in logs so that readers can see changes in growth rates over time.

Over the full period – 145 years – New Zealand’s population has grown materially more rapidly than Australia’s. Of course, the largest differences were in the first decade, but the gap hasn’t narrowed since.

I’ve often run the argument that New Zealand’s post-WWII immigration policy was materially misguided, at least on economic grounds, given the absence of new favourable productivity shocks or technological opportunities that would support top tier incomes for a rapidly growing number of people in these distant islands

Here is same chart starting from 1945.

You can see the period from the mid 1970s to the late 1980s when New Zealand had very low rates of net immigration, but over the full period New Zealand’s population growth has still modestly exceeded that of Australia.

And here is the most recent period since 1991 – which uses official New Zealand population data, and ties in quite well with the change in immigration approach in New Zealand that largely prevails to today.

Again, our population growth has been a bit faster than that of Australia.

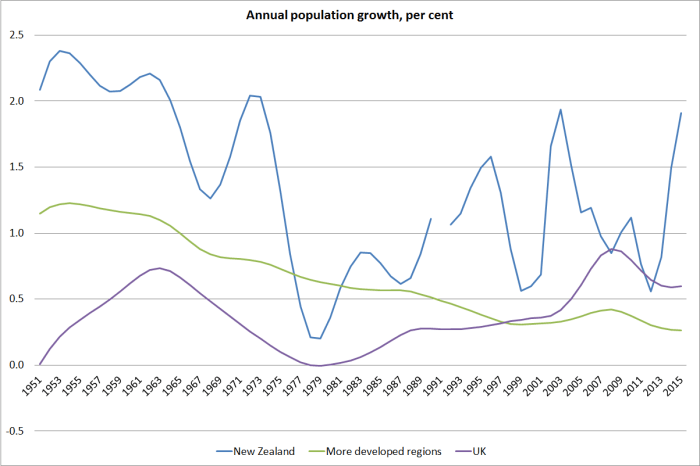

Now it is perfectly true that in the immediate post World War Two period, Australia was much keener on taking continental European migrants than we were. Then again, in the 1960s and 70s we had large inflows of Pacific Island migrants, and there was nothing comparable in Australia.

But, and here is my other key point, we’ve had faster population growth than Australia even though we’ve had huge outflows (net) of New Zealand citizens, that swamp any outflow from Australia of Australian citizens.

Here are the numbers on the total net outflows of New Zealand citizens for each decades since the 1950s

| Net PLT outflow of NZ citizens (March years) | |

| 1950-59 | -2494 |

| 1960-69 | -34,057 |

| 1970-79 | -161,231 |

| 1980-89 | -229,874 |

| 1990-99 | -146,229 |

| 2000-09 | -263,651 |

| 2010-16 | -138,705 |

That is a total of 976000 people, from a country which at the start of the period had only 2 million people and now has around 4.6 million people.

Some of the people who left will have died by now, but official estimates reported by Statistics New Zealand suggest 600000 New Zealand born people living abroad (and perhaps 1 million New Zealand citizens living abroad). Australia has five times the population of New Zealand, and yet estimates of the total number of Australians living abroad are around one million.

Yes, there are differences in rates of natural increase from time to time, but the big story of recent decades in particular has been one in which New Zealand has taken materially more non-citizen migrants (per capita) than Australia has, reflected in the slightly faster population growth we’ve had despite the huge continuing outflow of New Zealanders.

In fact, you can see this in the respective policy-controlled bits of the immigration programmes. This chart is cobbled together using data since the late 1990s on Australian permanent migration approvals under their Migration stream and Humanitarian stream, and New Zealand data on residence approvals. To the Australian numbers I’ve added the net inflow of New Zealand citizens to Australia, and to the New Zealand numbers the (much smaller) net number of Australian citizens moving to New Zealand.

Most years, the rate of permanent immigration of non-citizens to New Zealand has been higher – often materially higher – than that to Australia. And the Australian numbers have dropped back since the end of this chart as the flow of New Zealanders moving to Australia has fallen back.

Perhaps Cowen had some less numerical basis in mind for thinking that New Zealanders have been less welcoming of immigrants than Australia. But I’m not quite sure what it could be (although there is always this site). And given our continuing economic underperformance, it is quite remarkable how receptive New Zealanders have been to such high rates of immigration (roughly three times per capita the size of net non-citizen inflows to the US and UK) – especially as the programme is repeatedly sold as an economic-based measure, a “critical economic enabler” in the words of the government department responsible for immigration policy matters.

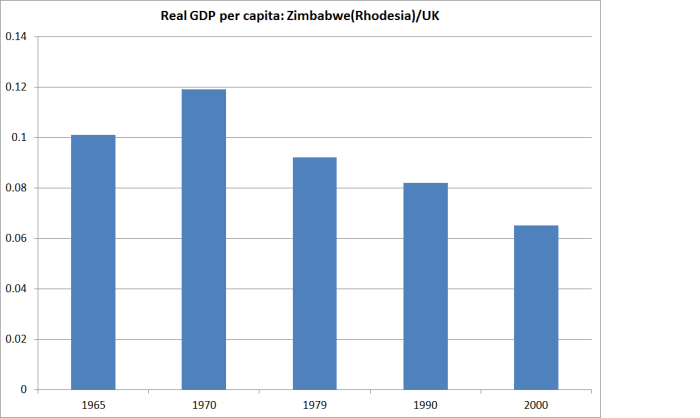

I’ve also shown the data for 1929 (the eve of the Great Depression) and 1939 (the eve of World War Two, which Ireland stayed out of). There is always a lot else going on, so the whole story of Irish relative economic decline isn’t (the policy choices/constraints that followed) independence. But much of it was. Today, of course, Irish real GDP per capita is higher than that of the United Kingdom.

I’ve also shown the data for 1929 (the eve of the Great Depression) and 1939 (the eve of World War Two, which Ireland stayed out of). There is always a lot else going on, so the whole story of Irish relative economic decline isn’t (the policy choices/constraints that followed) independence. But much of it was. Today, of course, Irish real GDP per capita is higher than that of the United Kingdom.