In the last day or so I’ve seen or heard two sets of comments from the Minister of Finance on the Orr/Quigley/Reserve Bank/Treasury/Willis – and it is now about all of them – business.

The first, that I want to deal with only briefly, was in The Post this morning under the heading “Willis dismay with RBNZ” (online here).

The journalist was obviously a bit of an Orr fan, as this article is the second time in two days The Post has talked of Orr’s “reputation for being charming”. No doubt he could and did turn it on when he chose, but not, surely, ever to anyone who ever challenged or disagreed with him (that included – very evidently – Nicola Willis when on occasion as Opposition finance spokesperson she asked Orr a slightly uncomfortable question at FEC hearings).

Much of what is in the article was also covered in my post yesterday. So I wanted to mention only this snippet

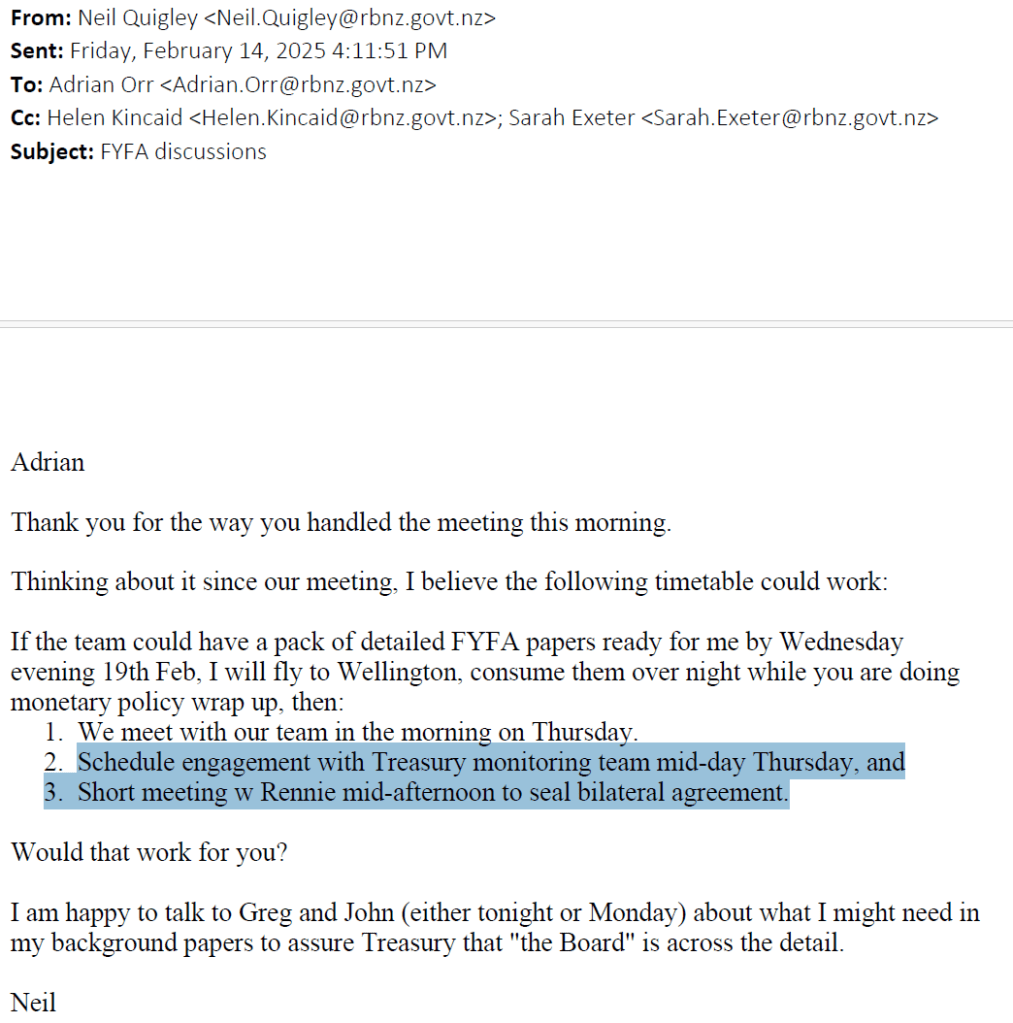

I guess she’d have looked a bit silly to have objected, but it is good to see her explicitly welcoming that Treasury release. On the second bit of that extract, it refers to the meeting on 24 February involving Quigley, Orr, Hawkesby, and senior Treasury people as well as the Minister herself. It is good to know that Treasury is considering releasing the minute of the meeting given that my request for it was lodged with them more than a month ago (as part of a larger request on Funding Agreement issues) but I presume there have been other requests, including since Tuesday when I reported the claim by my source that Quigley had been apoplectic and had complained to Treasury when he’d learned that such a minute existed. Again, it is good to know the Minister thinks Treasury should comply with the law, and we will look forward to the release.

The Minister’s more substantive comments were in an interview yesterday afternoon with Heather du Plessis-Allan. The audio is here and my transcript is here

Transcript of Heather du Plessis interview with Nicola Willis on 24 July 2025

Why do I bother doing the transcript? Partly for future reference and partly as a way of focusing my mind on all the lines Willis used in answering (and avoiding answering) questions. There were things I hadn’t really noticed when I listened live.

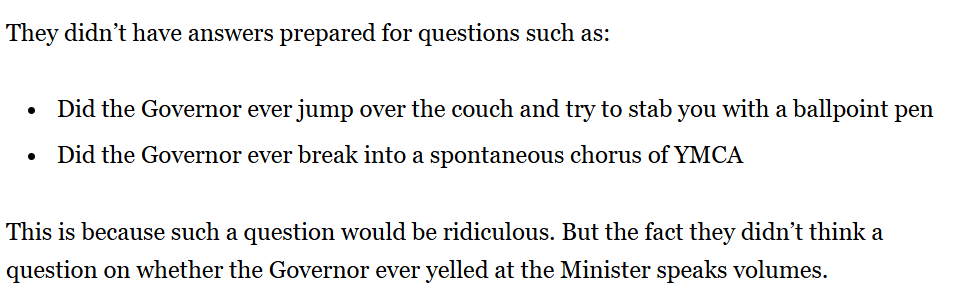

What do we learn from the interview? First that “emotions were running high” (the no doubt carefully chosen phrase for something like Adrian Orr losing his cool again) in the 24 February meeting she attended (although apparently there was no swearing) and she’d “heard reports” of the 20 February meeting between the Bank and Treasury where again “emotions ran high”. About, of all things, the Funding Agreement…..as if almost every single agency in Wellington hadn’t already been facing budget cuts (and it presumably wasn’t as if anyone was proposing cutting out the role of Governor).

Recall that Quigley email to Treasury (reproduced in yesterday’s post). The Governor was so ill-disciplined and out of control that in response to what Quigley recognised was a perfectly reasonable question from a mid-level Treasury official, Orr lost it, and then wouldn’t apologise, either immediately or after the meeting (instead Quigley was left to go and make his own apologies for Adrian). And sufficiently out of control, and unresponsive to what must have been feedback from his own chair, that the “losing his cool”, “emotions running high” behaviour was on display again several days later to a meeting with the Minister himself. In a normal employee such behaviour, especially repeated and without prompt and full apology, might of itself almost have been grounds for dismissal. (Humans make mistakes, even public sector chief executives, sometimes provoked, sometimes not. But when made aware you apologise, ensure it won’t happen again, or….you really aren’t fit to lead people and public organisations.)

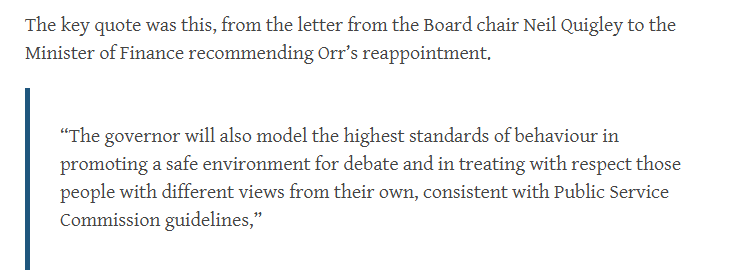

Willis was again at pains to suggest that the employment of the Governor was nothing to do with her, but purely something for the Reserve Bank Board. As a matter of law it simply isn’t so (I ran through the relevant provisions a couple of days ago), and the fact that it isn’t so has nothing to do – contrary to the Minister’s claim – with the “independence” of the Reserve Bank. There are plenty of roles and powers for the Minister of Finance in the Reserve Bank Act (as well as appointing and dismissing and receiving resignations from the Governor). For example, the Reserve Bank has what is known as “operational autonomy” on monetary policy, but they work to an inflation target by the Minister. In banking supervision and crisis management, some powers are exercised wholly by the Bank while others need ministerial approval. The Minister is directly party to the Funding Agreement. Parliament could have chosen to give the Minister no role re the Governor’s appointment etc but it never has (fortunately or there would be no political accountability at all). The Minister is responsible for the Governor, while the Board – whose chair is removable at will be the Minister – monitors etc the Governor, accountable to her.

At the very end of the interview Willis is asked

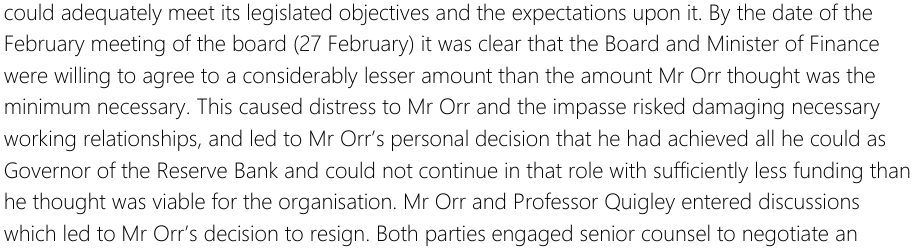

So far, we’ve had two quite different stories from Quigley, neither of which appears to be the truth. First, back on 5 March we were assured it was just “a personal decision”, with denials of any policy or conduct or similar issues being involved. We were intended to believe the man was tired, the job was done, and it was time to do something else. Then on 11 June, the Bank’s carefully crafted statement told us a new story. In this story there had indeed been material differences between the Board and the Governor over what they could live with in the next Funding Agreement. This we were told

“caused distress to Mr Orr and the impasse risked damaging necessary working relationships, and led to Mr Orr’s personal decision [ that term again] that he had achieved all he could as Governor of the Reserve Bank and could not continue in that role with sufficiently less funding than he thought was viable for the organisation”.

This time we were clearly intended to believe that the “personal decision” [which in a narrow and formal sense it was] was really just about (strongly felt) policy and resourcing differences.

Had you read either or both of those accounts, you might have believed (and were clearly supposed to) that the very first the Minister of Finance would have known that anything so dramatic was afoot was when on 27 February Quigley advised Iain Rennie of something briefly (words were withheld), who in turn advised the Minister briefly (words were withheld), who responded (puzzlingly) with nothing much more than something like “thanks for the update”.

But look at what the Minister said yesterday afternoon

You don’t usually have “employment discussions” when someone comes to you and says their job is done and they are going to leave, and even when the CE comes out of a Board discussion on funding and concludes it might be better for everyone if he, the CE, moves on. There will have been standard resignation and notice provisions in the Governor’s contract. Easy enough to have HR put those in train.

“Employment discussions” between the Governor and the Board preceding his resignation strongly suggest that serious issues were raised by the Board with the Governor, serious enough to have potential implications for whether they would be happy for him to continue as Governor. Which would be consistent with my source’s story, from the post on Tuesday:

And you can well understand why it might trigger Orr’s resignation, since getting to such a point clearly indicated a serious loss of confidence in the Governor, and quite possibly an almost irreparable breakdown of trust.

The Minister continues to state that she does not know the contents of the exit agreement then negotiated between expensive senior lawyers for both the Board and Orr. Which, on her account of what went on, should be simply extraordinary, because (a) the resignation would have to come to her, and b) she is the only guardian of the public interest here, and the one who would, in principle, have to account to Parliament for any deals done. She and her office, or at very least Treasury, should have been all over any terms – especially around non-disclosure matters – Quigley was agreeing with her (outgoing) Governor. And yet we must presumably take her at her word that she was not, and the OIAed paper trail suggests no Treasury advice on such matters at all.

One of the things that has puzzled me in the last few weeks is the absence of advice from either Treasury or the Board chair (or Board generally) to the Minister on the looming resignation. Last month I had an OIA response from Treasury (briefly written up and linked to at the end of this post), with almost nothing there (not withheld, just nothing there).

And then on 30 June I had a response to an OIA to the Bank. The relevant bit of the request was this

and their response was

Which isn’t exactly what you’d have expected if the initial Quigley spin had been anything like the truth or if the 11 June statement had been anything like the full story.

But it would make a lot more sense if the Minister of Finance had been the one initiating/prompting the actions that led directly to Orr’s “personal decision” to resign.

There is no direct evidence of that at this point. But something along those lines might explain rather a lot.

Let’s go back to that meeting on 24 February between the Minister, the top Bank people, and (presumably) very senior Treasury people. If Adrian had again lost his cool (“emotions were running high”) what do we supposed happened afterwards? Every one just put it down to a bad day and moved on? It doesn’t seem very likely. After all, we know that a few days previously Quigley had taken the initiative to apologise for Orr’s conduct to a mid-level Treasury staffer. Was he likely to have done much less after his CE blew up in a meeting with the Minister herself? As for the Minister, surely she’d have debriefed with her political advisers – “can you believe that?” sort of thing (of course, they probably could because Orr’s behaviour and style has been well known, including to the Minister, for years), or “we have to do something about him/something has to be done about him”. Perhaps she had a chat with Iain Rennie, or perhaps people in her office passed on the reports of the Treasury meeting a few days previously?

It doesn’t seem at all impossible – and I’m not sure any OIA so far (that I’ve heard of) would have captured this – that she, or someone senior acting on her behalf, got hold of Quigley (keeping Rennie in the loop) and indicated that Orr’s performance was intolerable, and that he really had to go. The specific incidents may have been like a heaven-sent opportunity, with Orr laying himself open, by having openly embarrassed the Board chair and Board as a whole, at a very delicate time re the Funding Agreement, by egregious behaviour – unacceptable in any official – in front of the two groups (MInister and Treasury) they needed to avoid antagonising to try to get a decent settlement. Perhaps Quigley intimated that he had a long list of behavioural issues re Orr that he’d built up over several years, and reckoned the Board would probably have had enongh too. Both sides will have known that only the Minister could fire the Governor – and she wouldn’t want to have done that directly – but it will have become apparent that they had leverage and could put pressure on, that would be likely to result in his “personal decision” to leave. And if something like that is what went on, maybe the Minister – conscious of maintaining semi-plausible deniability – indicated that whatever it took should be done, and don’t bother me with (or show me) the details.

It fits the facts we have better than any other story so far, including in making sense of why Willis has been so over the top in her disavowal of any involvement and insisting (contrary to the law) that hiring and firing etc Governors was just a matter for the Board, nothing to do with her. And, of course, of why there was an exit agreement – negotiated by senior counsel at all – with gag orders etc: they wouldn’t have been willing, probably, to directly fire Orr (judicial review has always been a risk too), and so he could insist on (some) terms, but it isn’t clear that Quigley isn’t using them to protect himself too.

If the truth is anything like this – another layer behind the story from my source, which itself so far looks sound – perhaps where they (the Minister in particular) misjudged was in putting too much confidence in Quigley to deal with the public side of things (if so, pretty inexcusable on her part as Quigley has no track record of being a deft and effective or trustworthy communicator). Both after 11 June and again yesterday the Minister has indicated that she isn’t satisfied with what the Board has said (or not said). From the interview yesterday

“I have also however previously shared my disappointment at the way information on this matter has been shared with New Zealanders. Today I had a prescheduled meeting with the entire Board of the Reserve Bank and at that meeting I sought to convey to everyone present that I was disappointed with the way that this matter had been handled given the ongoing public speculation because it is in New Zealand’s interest that the Reserve Bank maintains its reputation at all times and I think with better handling we would not still be having these interviews and this discussion.‘

Well, indeed, but what did you expect? They never seem to have had lines that they’d effectively stress-tested (to stand up for more than a few minutes – 5 March – or hours – 11 June) and hadn’t even got the process straight (witness what the Bank has already confirmed that the Minister was putting pressure on on the afternoon of 5 March for Quigley to do a press conference he didn’t really want to do – something surely that should have been sorted out in advance and properly rehearsed). The Minister clearly now isn’t that happy with the ongoing OIA obstructionism, and she is quite right to suggest that better handling of this whole thing would have seen it as yesterday’s story, one for next history of the RB, pretty quickly, perhaps within a week or two of 5 March. Instead, here we are, months on, and so many unanswered questions, including from the Minister herself, and with the Ombudsman all over the issues.

The Minister’s main message yesterday – to various outlets – was that she still had confidence in Neil Quigley as Board chair (which since she could have fired him at will and hasn’t we pretty well knew that by revealed preference).

But why? Some speculate that perhaps it has to do with the medical school – might not be a good look, might undermine confidence, to toss Quigley out the very week the government had granted him his controversial new medical school.

But it might also be that in some sense in fact she is deeply grateful to Neil Quigley, for having done the dirty work, possibly at her own bidding, and got rid of Orr. Perhaps somehow that compensates for the Clouseau-like performance over months since – only worse than Clouseau because it is quite clear that Quigley wasn’t just bad at this stuff, but that he had, and has, consciously and repeatedly set out to mislead New Zealanders.

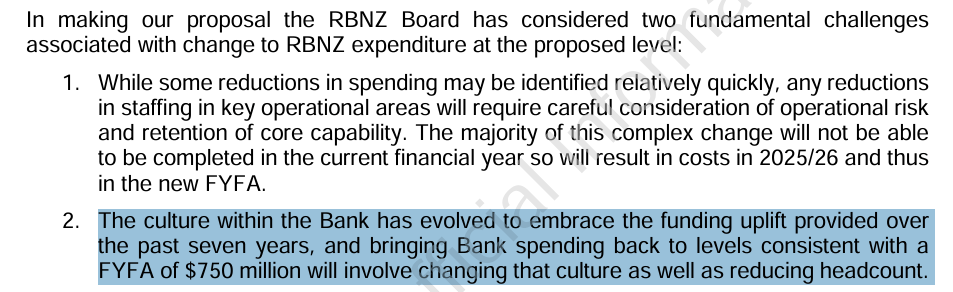

In one of those quotes a little way back up the page the Minister rightly stressed the importance of the reputation of a central bank. The Bank knows it too. This is from their recent Statement of Performance Expectations

But the problem is that we (and they) are starting from things as they are, and it is hard to see anyone with even a modicum of interest could have any trust at all in our powerful independent central bank and those who run it. There have been repeated policy failures, bloated budgets (and spending last year left to run wild while the Minister did nothing to rein in the Governor or Board chair), lies to Parliament, lies to the Treasury (see final bit of this post on Quigley and the first MPC), pretty weak (or worse) policy communications, top tiers of management currently held by people simply not fit for the job, a Governor with serious behavioural issues left unchecked for years, and now all this……the active misleading, the cover-up, and (from the chair) the sheer disdain for any sense of public accountability or interest. Oh, and a Minister who did nothing about any of this for her first year or so in office – about conduct, about fiscal excesses, about replacing the chair, about filling board vacancies, about simply insisting on something a lot closer to both excellence and openness.

And that is among the reason why Quigley really should resign or be sacked now. There will be a new Governor later in the year. That person will need to sweep clean. But how can we have any initial confidence in a new Governor – whether some stray Canadian hand-me-down not likely ever to make Governor at home, as speculated in the press the other day, or whoever – when that person has been selected by a process led by the same chap who delivered us Orr in the first place, who championed his reappointment despite all failings being evident by then, who presided over that budget-blowing (well Funding Agreement blowing) last year, and who can’t or won’t even give a straight story – somewhat diplomatic as it might have to be – about the early departure of the last Governor.

Anyway, some questions to ask. Perhaps the story here is also nothing like the truth. But it is beyond time for the truth to be told and a clean breast to be made of things. And if what happened is something like what is suggested here, it should mean some very serious questions indeed for the Minister of Finance as regards her part in misleading New Zealanders. Not exactly a sound basis for trust.

(UPDATE: To be clear, if the Minister did engineer Orr’s departure along these sorts of lines, then well done her – found an opportunity and seized it – and there should be no harrumphing about affronts to central bank independence. But the subsequent spin, misdirection etc would still raise very real questions.)