In various posts over the years I’ve mentioned how countries finally got out of the Great Depression. Generally that involved breaking the link between their respective currencies and gold and then being able to adopt more-expansionary macroeconomic policies. That was relatively easy to do as a purely technical matter, but it took a long time for countries to get there (a handful of significant countries not until 1936). I’ve worried aloud that given how low the starting point for nominal interest rates was going to be that in the next serious downturn the refusal of central banks – and it is simply a refusal – to take policy rates deeply negative would end up as much the same sort of fetter as gold once was.

The definitive book-length treatment of this angle on the Great Depression is Berkeley professor Barry Eichengreen’s Golden Fetters. It was published in 1992 – decades ago now – and going by the marks in the margin of my copy I seem to have read it once a crisis since then. It is one of those books that repays rereading, partly because the contemporary context against which one reads it is different each time. I read it again last week.

What follows is informed by Eichengreen, although refracted through my lenses. There are places where Eichengreen’s argument isn’t fully persuasive (and he has one or two facts wrong about New Zealand).

Much of the book is scene-setting for the experience of the Great Depression. That includes a perspective on the pre-War Gold Standard, which tied together most of the major (and many of the minor) economies of the time, with a leadership role played in particular by the Bank of England. In many of the core countries – UK, France, Germany notably – central banks played an important role, but in other countries operating on a gold standard there was no central bank at all (most importantly, the United States, but also countries like New Zealand and Canada- all three of whom were net capital importers). Price levels didn’t change much over time (the British price level was about the same in 1914 as it had been in 1834), capital flowed freely, trade (and migration) was extensive, and if there were periodic crises or threats to the system, central banks worked together to maintain stability.

World War One greatly disrupted the picture. Some countries formally went off gold, others didn’t formally but there were enough interventions that the pre-war parities didn’t act as any sort of constraint on price levels. Huge debts – internal and external – were run-up in the process, and the US moved from being a net borrower to being a net lender to the rest of the world. And in the aftermath of the war there were reparations obligations established, huge distributional fights (inside countries) as to who should cover what portion of the accumulated costs, and some countries collapsed into hyperinflation sooner (Austria) or later (Germany). All manner of other countries had much higher price levels than pre-war, and in some – notably France – high inflation remained an issue well into the mid-1920s.

Against that backdrop, in many quarters a return to a money convertible to gold was seen as partly as a key confidence-building commitment, and partly as a return to something like normality. It took a long time – in one case, Japan, it din’t actually happen until early 1930 – and for good reason. There were debates about which rate to restore parity at – the UK eventually, perhaps unnecessarily, chose to re-peg at the pre-war parity, which implied several more years of moderate deflation. For France, having had so much inflation, the pre-war peg quickly became unrealistic and they stabilised at a considerably devalued exchange rate to gold. For Germany, of course, hyperinflation made a nonsense of the pre-war parity.

There hadn’t much gold mined in the previous few years, and yet global price levels were much higher than they had been. That in itself posed some challenges. But international cooperation and trust wasn’t what it had been pre-war either. And particular policy choices made by the US and France meant that those two countries’ central banks accumulated an increasing share of the world’s gold are were unwilling and/or unable to let those inflows flow into much looser domestic monetary conditions (France, for example, having just stabilised was understandably averse to a fresh wave of inflation). The UK – still operating as a major global financial centre, significant source of long-term foreign lending – operated with low gold reserves. Germany, with a populace only too conscious of hyper-inflation just a few years previously, had high minimum gold cover requirements, but those buffers couldn’t be cut into. Higher interest rates in the US – as in 1928/29 – forced both the UK and Germany to adopt tighter domestic monetary policy. And so on.

The Depression itself got underway in a variety of countries influenced by various factors, domestic and international. The 1929 sharemarket “crash” wasn’t particularly important, except perhaps in shaping the mindset of various US policymakers (including at the Fed) who were uneasy about much looser monetary policy because they reckoned the excesses of speculation needed to be purged. Some countries were affected worse than others early on – Australia for example on the worse side, and France on the more positive side.

Generally, however, monetary conditions did ease as the respective economic conditions deteriorated. But the fixed exchange rate system, underpinned by convertibility to gold, severely limited what could be done with either fiscal or monetary policy – and that was true even in the countries with large gold holdings, the US and France.

The financial crisis aspects really intensified in mid-1931, in Austria and Germany (where there were significant domestic banking system issues) initially, and then spilling over to the UK, where the economic slump itself had been relatively mild – relative being the word – but the pressure eventually told on gold parity. The re-formed National government – still led by former Labour Prime Minister Ramsay McDonald – decided not to impose further pain on the domestic economy (which might have been insufficient anyway) and went off gold. The break in the parity was initially envisaged as temporary, and it was some months before domestic policy itself became much more expansionary. But the consequence of the lower exchange rate – although many smaller countries moved to peg to sterling, giving rise to the “sterling area” which persisteed for several decades) and easier domestic monetary conditions meant that the UK was the first significant economy to recover from the Depression.

The US held on to the old gold parity until April 1933, and while that old parity held it acted as a real and binding constraint on the ability of domestic authorities – including the Fed – to run much easier policy. Fear of devaluation sparked capital (and gold) outflows. But as Eichengreen records, many of the senior Fed officials were not that keen on much easier policy anyway, and some saw the roots of the Depression primarily in past speculative excesses. Even in the US, concern about possible inflation risks – in the depths of a deflation – were heard, and were evidently sincere. The US later returned to a gold parity (while prohibiting for decades citizens from holding gold) but at a much-devalued exchange rate.

Those inflation concerns were all the greater on the Continent. Germany never abandoned the old gold parity, but just rendered it non-binding with an increasing complex of exchange controls and other payments restrictions. But for the remaining gold countries – most notably France, Belgium, Netherlands and Switzerland – the tensions grew between the desire to maintain the parity – whether as symbol of normality or (more strongly in the French cases) ran increasingly up against the losses of competitiveness producers in those countries faced as other countries devalued, and the market recogmition of those pressures (thus capital flight). It wasn’t until 1936 that those parities were finally abandoned.

As Eichengreen notes, at the end of it all, by the late 1930s, real exchange rates among the major economies had not changed that much at all. Some countries had got the initial advantage of moving earlier (the UK notably) but in the longer-term the beneficial effect was not breaking the gold parity and getting a lower exchange rate, but breaking the constraints (domestic and international) on domestic macro policy (fiscal and monetary). As he also notes, it wasn’t enough just to break from gold, since countries also had to be willing to break with the Gold Standard ethos, and allow/adopt looser macro policies. One obstacle to that had been the fear of inflation. That fear might look unreasonable – whether from this standpoint, or contemplating a country with a deep deflation in the early 1930s – but the hyperinflationary and high inflation experiences really weren’t that far in the past, and had been utterly destructive for many.

Eichengreen has a nice table late in the book illustrating how industrial production – the main macro variable at the time, before quarterly national accounts were a thing – responded in different groups of countries.

Look at the last two columns and you can readily see the difference of experience in the countries that went off gold/devalued (sterling area and the “other depreciated currencies” lines) with the experience in the gold bloc countries, where even by 1935 industrial production was still 20 per cent lower than in 1939.

Look at the last two columns and you can readily see the difference of experience in the countries that went off gold/devalued (sterling area and the “other depreciated currencies” lines) with the experience in the gold bloc countries, where even by 1935 industrial production was still 20 per cent lower than in 1939.

It need not have been. It wasn’t as if the 1920s and 1930s were a period of underlying economic stagnation. The US – by then the world’s leading edge economy – experienced really strong total factor productivity growth in both the 1920s and the 1930s. I’m sure some economic ups and downs were inevitable, but nothing on the scale and duration of what actually happened in the 1930s was in any way inevitable – it was largely the consequence of a succession of choices, of almost entirely well-intentioned people, working against the backdrop of presuppositions, presumptions about normality, and the backdrop of some deeply unsettling experiences, that led to those savage and prolonged losses. When countries broke the golden fetters – and for many it was regretted initially or felt to be hugely risky – economies started to recover, and the gains in an increasing number supporetd a sustained global recovery in demand.

(You might be wondering where New Zealand fits in all this. That is mostly another post. We had no central bank. We went off gold in 1914. That left our banks issuing their own currency, in practice loosely pegged to sterling (but not legally so), with banks managing domestic credit based on their holdings of London funds. Our exchange rate – managed by the banks – was allowed to depreciate a bit, but the big movements were in September 1931 when the UK went off gold and their exchange rate depreciated against the rest of the world and so, thus, did ours, and – more importantly – then in January 1933 when the government initiated a formal devaluation against sterling (still not having a central bank) over the objections – and resignation – of the Minister of Finance (and with not a little domestic unease and debate). In 1931 and 1932 even after the UK went off gold our economic policy options were very very few, and our devaluation was much more of a turning point (probably helping that it was followed a couple of months later by the beginnings of the US reflation). I have an old post on New Zealand and the Great Depression.)

Of course, the point of the post is to draw some loose comparisons between the golden fetters of the early 1930s, which proved so costly in the specific circumstances of the time, and what I’ve taken to calling the paper chains, the refusal of the world’s central banks now to do anything about taking official interest rates deeply negative, even though standard macroeconomic prescriptions – such as the Taylor rule – suggest that is exactly what should be done.

I’m not suggesting it is some sort of allegory for our age, in which every detail of the 1930s can be mapped to something now. It can’t. It is really just about a single point: that self-imposed constraints, which can seem very very important to preserve at the time, can actually in some circumstances prove incredibly costly, and in those circumstances the sooner they are jettisoned the better.

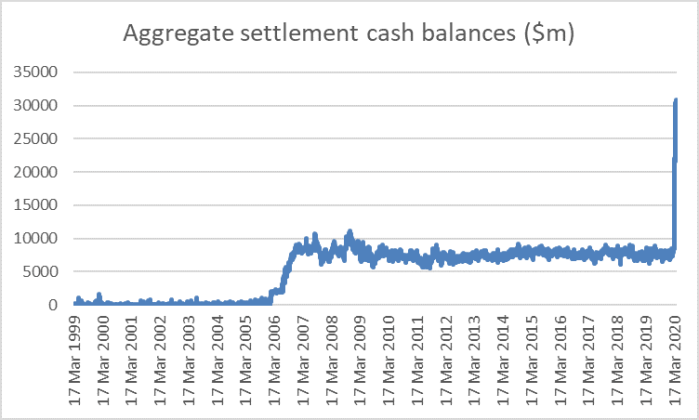

One area in which the parallels certainly aren’t exact is around fiscal policy. Most countries in the 1930s had very little freedom of fiscal action initally, precisely because of the monetary/gold parity constraints – increase your fiscal deficit and the resulting increase in demand will also result in increased current account outflows (of gold). In some cases – New Zealand – there was just no effective borrowing capacity at all – thus, Keynes’s advice to Downie Stewart that I’ve quoted here previously (“if I were you I’d try to borrow; if I were your bankers I would not lend to you). We have nothing like those sorts of technical constraints. But that doesn’t mean there are no limits in practice – as we saw after 2008/09, public tolerance of continued very large ongoing fiscal stimulus, even in badly affected countries, was really quite limited. In the real world, fiscal policy isn’t any sort of fully adequate substitute for monetary policymakers choosing to sit on the sidelines – dealing, perhaps, with market liquidity issues, but not doing much about the overall stance of monetary policy, even as deflationary risks mount (thus, real retail interest rates have not fallen at all in New Zealand and Australia this year, despite the huge economic slump).

There is a, perhaps understandable, sense in some quarters that there wasn’t too much wrong with economies last December. Perhaps, but things have now changed, and if one strand of macro policy – typically the most important for cyclical purposes, and easiest to adjust – is allowed to sit on the sidelines doing nothing – and elected ministers have the power to change thatg – there is risks that this economic downturn ends up much more severe and protracted than it needs to be. All because central bankers won’t break free of their paper chains and their old mindsets (aggravated in New Zealand’s case by the stunning negligence of a Reserve Bank that talked modestly negative interest rates for some time but did nothing at all to ensure there were no technical/systems obstacles): we pay the price for both lack of preparation and the reluctance/refusal to break the paper chains and put in place quickly the sorts of rules and practices that could allow official rates to be taken deeply negative for a time, in turn supporting demand (directly and via the exchange rate) and supporting medium-term expectations about the economy and inflation.