A few weeks ago the Minister of Finance announced that the government’s Budget would be delivered on 14 May. That really isn’t far away now. I noticed the Minister, on TVNZ’s Q&A yesterday, suggesting the timing was opportune in light of the coronavirus. Perhaps, but contemplate some relevant dates. Last year’s Budget was delivered on 30 May and according to the documents these were the relevant deadlines

Assuming much the same sort of timetable holds this year, the economic forecasts the Budget draws on will have to be finalised in not much more than three weeks from now. The tax and other fiscal forecasts are finalised later but they draw on the economic forecasts. And who supposes that there will be any meaningfully greater certainty in three weeks time than there is now? In truth, the Budget economic forecasts will be little more than (well, really less than given the long publication lags) one potentially useful scenario. They simply aren’t going to be – and can’t be – any sort of useful guide for policy in the current climate, and I hope the Minister and the Treasury Secretary (the forecasts are Treasury’s and the Secretary has to sign off on them) start making that clear soon. Consistent with that, in setting budgetary policy no one should be getting hung up on (for instance) whether the bottom line is a small surplus or small deficit. Any such forecast number – in a period of extreme uncertainty – will be just meaningless.

In his interview yesterday the Minister of Finance seemed to be saying much the same sort thing as in his speech on Thursday. Much of it was, at one level, sensible enough, but to me it fell a long way short in grappling with the likely severity of the issues, and the related uncertainty, and with the vulnerability of the world economy and the limitation of current macro policy. Perhaps it was partly what he was (wasn’t) asked, but he is an experienced politician and knows how to get across the messages he wants to convey. When community outbreak becomes a significant thing here, there is going to be a lot of economic disruption (even in the most optimistic cases abroad, eg Singapore, containment so far has appeared to rely on extensive social-distancing – voluntary and compulsory – none of which is conducive to holding up short-term GDP (or similar indicators).

But even pending that, what will be happening to tourism right now? We know tourism from China collapsed a month ago – first PRC restrictions and then our own – but what about travel from other markets. How many people are going to be keen on booking new trips, or even – if they have the option – embarking on new trips now? I don’t know about you but I flicked through the travel sections of newspapers yesterday and today, wondering quite how many takers there would be. Allowing for both direct and indirect effects, tourism is estimated to be about 10 per cent of the economy and about 55 per cent that is international tourism. Even if international tourism only halves for the duration – and it would be a lot lower than that if there is significant community outbreak here, that alone is equivalent to taking almost 3 per cent out of GDP. Sure, there is scope for some switching – more domestic tourism, as New Zealanders pull back on their foreign travel – but a couple of nights in Picton is for most hardly a substitute for the trip to Disneyland. And, of course, there are more and more reports of business travel – typically higher-end – being cancelled. And all of that is just one sector of the economy: that associated with foreign travel. It takes no account of scenarios in which people are unable to work, whether because of illness, movement restrictions, school closures or whatever.

There is simply no way of knowing how long or how deep the economic effects will be, or (for example) what public psychology – including eagerness to spend and to travel – will be like as the world gets through the other side. But with strongly asymmetric risks I reckon there is a pretty strong for an aggressive macro policy response. And some part of that clearly has to be fiscal, especially given the failure of authorities – here and abroad – to deal with lower bound constraints on monetary policy (covered in my post on Friday). If you are sceptical that I’m over-egging the monetary policy limits point, I’m not nearly as pessimistic as the local ANZ economics team

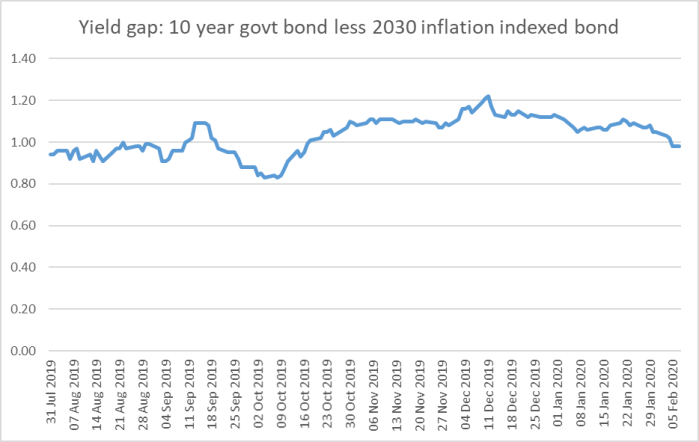

Not as pessimistic only in that I think the OCR can usefully be cut further than they believe. But if they are right and we really will be at the conventional limits of monetary policy by May (the day before the Budget in fact) people really should start worrying, because the ANZ economic scenario is not as bad as it could get. And there are few additional buffers that people can really count on in planning and forming expectations (including of inflation).

There has been quite a bit of talk about how monetary policy (and aggregate fiscal policy for that matter) can’t solve immediate problems – even bizarre articles from people who should know better suggesting there is some sort of either/or dimension between medical solutions and macro policy responses. And that is true, of course. Macro policy can never deal with the sectoral effects of sectoral-focused shocks. Macro policy is about stabilising the wider economy. Macro policy also can’t do a great deal in the very midst of a crisis – financial or otherwise. But what it can do in the midst of a crisis – perhaps especially a disease one, where moral hazard concerns are less of a worry – is better than nothing (easing servicing burdens, easing the exchange rate, signalling activity, leaning (a little) against collapses in confidence etc). Perhaps more important is the value of such tools when either the immediate crisis passes and we are left with chronic weakness in demand (perhaps for a few quarters, perhaps longer) and during the recovery phase. Macro policy tools work with a lag, and it is well to get adjustments in place pretty early (which is why monetary policy flexibility is so good to have: it is a very easy instrument to adjust, including to unwind when the need has clearly passed).

What sort of fiscal policy? I’m not that interested in specific assistance packages to individual sectors. In some cases, that sort of action might be justified, but much won’t really be – and the announcement a couple of weeks ago of funding to promote non-Chinese tourism looks even sillier now. Realistically, political considerations are likely to be more important than anything else in shaping those sorts of handouts, but (fortunately perhaps) such specific interventions/distortions/bailouts aren’t likely to be large enough to materially respond to wider weaknesses in aggregate demand.

And whatever you think of the case for more – even much more – government infrastructure spending, there are long lags to getting any such projects up and going. The case for a second Mt Victoria tunnel in Wellington might be rock-solid – and it is even in Grant Robertson’s constituency – but it is no sensible part of a response to a coronavirus-induced recession, even if (say) you worried about several waves of the virus over a couple of years.

Generalised tax cuts in income tax rates – which might or might not make sense longer-term – aren’t particularly effective because (a) the overwhelming bulk of any cut would go to higher-income households, (b) there is no particular incentive to spend (and some of the things higher income people might othewise spend on – an extra overseas holiday – aren’t likely to be so attractive in the next few months, and (c) as the Minister observed in his interview yesterday, such cuts tend to be permanent.

One could do, as Hong Kong announced last week, some sort of lump sum distribution – perhaps $1500 payment to each adult. It is much more concentrated ($ value) towards people likely to spend additional cash, but it is still less likely to be spent at the height of a crisis than in other circumstances, just because people will be (eg) staying away from shops. But perhaps a more significant issue is precisely that it is one-off – you might get a one-month lift to demand and activity, but the situation is reasonably likely to require longer-term support than that.

The point of this past was really to explore one other option I haven’t yet seen mentioned: an explicitly temporary reduction in the rate of GST. The idea has been around for a while, it was tried by the United Kingdom as part of their macro policy response in 2009, and was discussed in some detail in a paper presented in New Zealand almost 15 years ago by the (then) academic economist Willem Buiter, who had also served as a member of the Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee.

Buiter was invited to New Zealand as part of a focus in the mid-2000s (including this work) looking at possible tools that might enable more downward pressure to be maintained on aggregate demand – keeping inflation in check – without the concomitant upward pressure on the real exchange rate; the latter having become something of a sore point with both the Governor and the Minister of Finance. One element of that involved inviting four international experts to offer advice. The resulting papers, and discussant comments, are here. Buiter was invited to focus on fiscal policy issues and his specific paper is here. One of the options he explored (from p51 at the link) was using a temporary change in the rate of GST.

As a stabilisation option, supplementary to whatever monetary policy can do, a variable GST rate has one very big advantage relative to most fiscal options that are often touted. Not only does a temporary cut put more money in the pockets of households – and do so in a moderately progressive way (whatever lifetime consumptions patterns, in any particular period low income people typically spend a larger proportion of that period’s income, and face tighter credit constraints) – but it provides an active incentive to spend now because you know that prices will be more expensive later. Take as an example, an announcement that the rate of GST would be lowered by 2.5 percentage points for a year. For a person/household facing the choice between saving and spending now, at the start of the period, it is akin to a 250 basis point cut in interest rates. As the year goes on, the (annualised) effect gets even stronger (as we’ve seen with past GST increases, spending is brought forward to just before the increase).

There are all sorts of drawbacks with this instrument in general, whether used for temporary increases or temporary cuts, including judging when it would be appropriate to deploy the instrument (relative to, say, using monetary policy). Buiter favoured an independent committee – akin to an MPC – having the power to adjust the rate (something which I’m old-fashioned enough – only Parliament should change tax rates – to find abhorent). But this is an unusually stark situation (and may well be starker still by Budget day) – as, in a different way, was the UK financial crisis in 2008/09. It is not just a matter of slowly accumulating pressures (or lack of demand pressures) but a stark, truly exogenous (to the New Zealand economy) event. Defining a trigger for action shouldn’t really be a problem. And we are very close to the limits of conventional monetary policy, so the tradeoff-among-instruments questions also presents less starkly than Buiter would have imagined.

One of the other drawbacks – which the UK ran into – is defining an exit point. The period of weak demand around the world lasted much longer than any authorities expected in 2008 when they were devising responses to the financial crisis/recession. The extent of that weakness was hard, perhaps impossible, to foresee. With a pandemic virus perhaps it is a little easier – these things tend to sweep through in perhaps 12-18 months (even in 1918) so – for example – a cut in the GST rate announced/implemented in May, to end at end of 2021 might seem reasonable (while still providing a substitution effect signal). And if, spare us, at the end of the next year severe problems still faced us, then realistically choices could still be made then about whether to proceed with raising the GST rate or not (to not do so should require new legislation) – there shouldn’t be (but who can really imagine) the same debates about whose fault it was the banks had failed etc.

One other drawback in the risk to inflation expectations. Cut the rate of GST by 2.5 percentage points and the level of the CPI will fall by perhaps 2.1 per cent – and the reported annual rate of inflation will be that much lower than otherwise for a year. With a heightened risk of inflation expectations sliding away, there is a risk that those headline effects could accentuate the problem, even though none of the core inflation measures – the ones most analysts emphasise – would fall. There is no easy way to know how large this effect would be, and it would be quite circumstance-dependent. If, for example, the New Zealand dollar fell sharply – as it usually does in severe adverse global events – the direct price effects of more expensive imported tradable goods would lean against the GST effect on headline inflation (the UK, for example, had a sharp fall in its exchange rate around 2008/09). And if the temporary GST cut was part of an aggressive multi-faceted (monetary and fiscal) stabilisation package, the (helpful) demand effects might well outweigh any risks of adverse headline effects on expectations.

The other downside concern might be implementation lags. When I was around these sorts of discussions, IRD used to emphasise that these sorts of changes couldn’t be done overnight. Announce on Budget day a GST cut starting three months hence, and the risk is that you worsen things in that three month period. But when I went back to check the UK experience, I found that the policy had been announced on 24 November 2008, to come into effect on 1 December 2008. If a change can really be implemented that quickly – and hard to see why New Zealand IRD should be less capable than HMRC – a one week disruption might be tolerable.

Finally, relative to using monetary policy more heavily, fiscal options will tend to hold up the exchange rate more than otherwise. That might be less of concern in a scenario in which it has fallen a lot anyway and – as importantly – monetary policy options are approaching their limits.

I am not, repeat not, recommending that the rate of GST be temporarily cut, even on the assumption that the economic situations looks as bad or worse late next month when final Budget decisions have to be made. But, in a highly policy-constrained world, it looks like an option that should be pulled out of mothballs and looked at fairly closely by the Minister’s advisers, including a closer review of the strengths and pitfalls of the UK experience. In situations like the one we seem to find ourselves in – with the world one shock away from exhausting normal macro policy capacity, and that shock now seeming to be upon us – it is probably better to err on the side of doing more rather than less, and to consider taking risks with instruments that would not normally count as ideal (in which category I put the variable GST).

And whether or not the Minister of Finance thinks it an option worth exploring, I’d welcome comments here, including from those closer to the operational details of GST than I am.