There is a bit of discussion around (internationally more so than in New Zealand) about the possible merits of raising inflation targets, to something centred on 4 or 5 per cent annual inflation, rather than the 2 per cent focal point of most countries’ targets today. The main argument for doing so is to raise nominal interest rates in more normal times, in turn creating scope to cut policy interest rates further in real terms in future serious downturns.

I doubt it is a viable option at present for most inflation targeting countries, simply because most have largely exhausted conventional monetary policy capacity – policy interest rates are already near or below zero – and many are struggling to achieve their current inflation targets. It is, probably, still an option for New Zealand (with the OCR still at 2 per cent), although in my view raising the target is less attractive an option than taking action to reduce the impact of physical cash in creating a near-zero lower bound on nominal interest rates. The costs of positive inflation rates may not be that large, but they increase as the target inflation rate increases – and perhaps especially so in a country like New Zealand where income on financial savings (eg interest, which includes compensation for inflation) is taxed just the same as labour income.

Unlike most inflation targeting countries, New Zealand does have a history of having raised its inflation target. We started out aiming for 0 to 2 per cent annual inflation rates, and then raised that target to 0 t0 3 per cent at the end of 1996, as one aspect of the National/New Zealand First coalition deal. The Bank acceded to the change, but had not sought it.

Yesterday I was asked a question about the background to the second increase in the target. In September 2002 the inflation target was raised from 0 to 3 per cent per annum, to the current 1 to 3 per cent per annum. Why? My short answer was “politics”, and this is my fuller answer. I was quite closely involved – at the time I was one of the Governor’s three direct reports – but others will no doubt have slightly different memories/perspectives.

The opportunity for a change in the Policy Targets Agreement (PTA) opened up when in late April 2002 the long-serving Governor, Don Brash, unexpectedly announced his resignation from the Bank, effective immediately, so that he could contest the forthcoming general election as a National Party candidate. Key figures in the governing Labour Party – in particular the Prime Minister, Helen Clark – were furious, including with the Reserve Bank’s Board which had agreed terms and conditions with Brash that had not required any stand-down periods when he left office. I can’t speak for all my then colleagues of course, but my impression was that many people at the Bank, while perhaps wishing Don well personally, thought that resigning as Governor to go straight into party politics wasn’t quite the done thing, and risked undermining (albeit at the margin) the reputation of the Bank.

The Bank’s (and Brash’s in particular – as single decisionmaker) stewardship of monetary policy had been contentious in some circles for a long time. Both National and Labour stood solidly behind the Reserve Bank Act, and especially its monetary policy arrangements, but the Minister of Finance, Michael Cullen, had been uneasy for a long time as to whether the target framework was too restrictive. Back in the mid 1990s, as Opposition Finance spokesman, he had actually campaigned to widen the target band to -1 to 3 per cent per annum, and when he had become Minister in 1999 he added to the PTA the explicit requirement to “seek to avoid unnecessary instability in output, interest rates and the exchange rate”. No one ever – in fact, still – knew quite what it meant, but it was a response to the continuing unease, including that around the monetary conditions index debacle of 1997 to 1998.

The Labour-Alliance government which came to power at the end of 1999 commissioned, as had been promised, an international review of New Zealand’s monetary policy arrangements and the conduct of monetary policy. Michael Cullen wasn’t looking for radical change – or he would not have appointed Lars Svensson, one of the academic experts on inflation targeting, as the reviewer – although there was a sense that he would not have been averse to a recommendation to shift to a committee or Board system for making monetary policy decisions. In the end, the review was pretty tame – I was part of the secretariat, at the same time as being a Bank senior manager, and we went to some lengths to encourage Svensson not to be too effusive about the Brash stewardship, fearing that otherwise the report would lack credibility. Svensson did recommend a move to a committee system, but his proposal – for a committee of internal senior managers, somewhat akin to Graeme Wheeler’s Governing Committee – got no political traction. There was no political mileage in legislating to shift from one technocratic economist making the decision to four or five technocrats making the decisions.

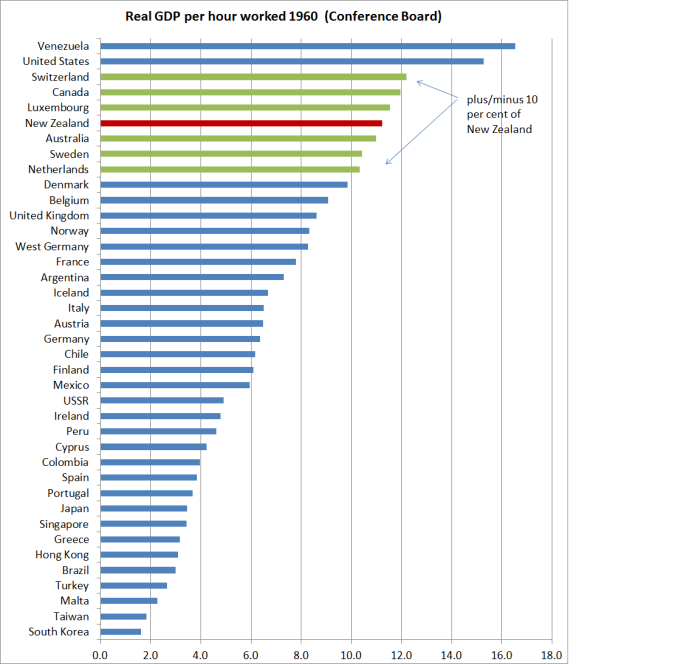

There was also longstanding unease, and puzzles, as to just why New Zealand’s relative economic performance had not improved. At the time, our exchange rate wasn’t high, but our interest rates were still high relative to those in the rest of the world, and there was no sign that the income or productivity gaps to the rest of the OECD were beginning to close. There was questions around whether somehow something in the way monetary policy was being run, or the way the target was specified, was somehow contributing to the medium-term real economic underperformance. Were we, for example, by holding interest rates so high unintentionally lowering potential GDP growth? In some circles there was a sense that the Bank jumped at shadows – raising interest rates at the first hint of inflation, and never “gave growth a chance”. As people pointed out from time to time, our inflation target was lower than Australia’s, but our interest rates typically weren’t.

Add into the mix the government’s unease with Don Brash’s views of the wider economic policy framework. His speech at the August 2001 Knowledge Wave Conference, on how best to accelerate economic growth, didn’t go down well with the government (understandably – I think those internally who had seen the draft were all pretty much of a view that it was material that should be saved for his retirement). It all seemed to just add to a sense that something was wrong at the Bank, and in how monetary policy was being run.

Actually, the Bank had been quite aggressive in easing policy during 2001, probably more so that (with hindsight) was warranted. The US recession, and the 9/11 attacks, prompted pre-emptive easings, from an institution determined not to make Asian crisis mistakes again. But by early 2002, the talk was turning again to the prospects for OCR increases. There had already been two 25 basis point increases by the time Don Brash resigned, and the projections and policy statements foreshadowed a lot more increases to come.

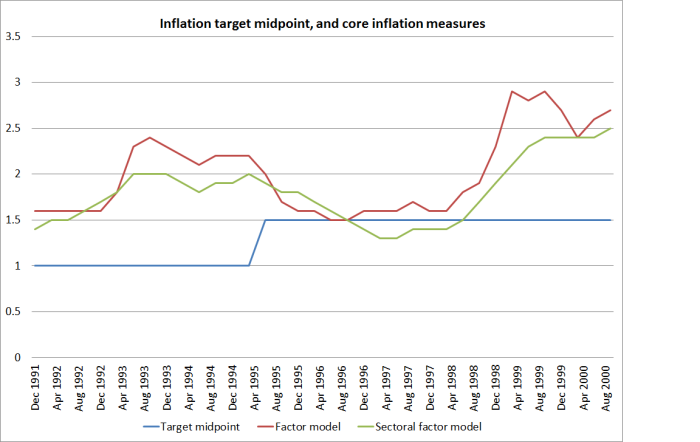

It is also worth remembering that, at the time, just over a decade into inflation targeting, the Bank had had inflation out-turns averaging well above the midpoint of the inflation target range. That track record continued right through until the 2008/09 recession, and it made us unusual by the standards of inflation targeting central banks – the more so, perhaps, because our rhetoric often stressed the importance of focusing on the midpoint of the target range (to maximize the chances the inflation would be within the target range). This chart illustrate the track record – although note that, at the time, we did not have either of these particular core inflation measures (they are just readily to hand).

Inflation had been above the target midpoint throughout almost all the inflation targeting period, had never (in core/underlying terms) been in the 0 to 1 per cent part of the range, and by now (mid 2002) inflation was not only in the upper half of the range, but was rising.

Deputy Governor Rod Carr was appointed as acting Governor once Don Brash resigned, and he took the next few OCR decisions, and did the associated communications. The OCR was raised at both of his first two OCR decisions, and in the May 2002 MPS in particular, Carr’s rhetoric was (and was widely seen as) very hawkish – words of man who might be champing at the bit to raise the OCR. The May projections had envisaged another 150 basis points of OCR increases over the following year or so which would, so the projections showed, bring inflation progressively back to around the middle of the inflation range.

In the Beehive, there seems to have been a sense that they definitely didn’t want the Board nominating a “Brash clone” as Governor, and a real unease about what another 150 basis points of OCR increases would do to the prospects for the sort of “economic transformation”, including the growth in the export sector, they were seeking. What, people might have asked themselves, was the point of having really large OCR increases to get inflation to the midpoint of the target range when it had never been there for long previously? And since (core/underlying) inflation had never been in the zero to one percent part of the target range, why not just pull the range up a bit? To do so, it could be argued, wouldn’t change anything much.

Throughout this period, Bank staff were at work on a major series of background briefing papers to help whoever was nominated as Governor, and perhaps the Minister, in negotiating a PTA. For the first time, since the Act had come into effect, we passed the real possibility of an outside appointee, perhaps with little or no background in monetary policy. I can’t now see that collection of papers on the Reserve Bank’s website (but will happily link to them if they are there: UPDATE: they are here) but suffice to say that they did not advocate a change to the PTA, or to the inflation target specificially. They were not, by any means, doctrinaire on the importance of the current target range, but saw little prospect of any real economic gains from raising the target.

In the Beehive, there was also a bit of a sense that if Australia could do just fine – indeed, so it was seen, to prosper – with an inflation target centred on 2.5 per cent annual inflation, perhaps we should move to adopt the same target. I gathered that the Prime Minister in particular was quite keen on that option.

In the end, the Secretary to the Treasury, Alan Bollard was appointed as Governor. He agreed to change the target in two ways.

The first was eliminating the 0 to 1 per cent part of the target range, so that in future the target would be 1 to 3 per cent annual inflation. My understanding/memory is that he did not see this as a route to higher inflation, but rather to cementing in something more like the average inflation outcomes of the previous few years. But it ruled out the need to tighten simply to get back to a target midpoint on 1.5 per cent. To Alan’s credit, he strongly resisted the Prime Ministerial preference for adopting the RBA’s target, centred on 2.5 per cent. Staff advice was that a target as high as that could not really be considered consistent with the statutory requirement to pursue and maintain price stability.

The second was to introduce the concept of a medium-term horizon explicitly into the PTA, as in these extracts

For the purpose of this agreement, the policy target shall be to keep future CPI inflation outcomes between 1 per cent and 3 per cent on average over the medium term.

3. Inflation variations around target

a) For a variety of reasons, the actual annual rate of CPI inflation will vary around the medium-term trend of inflation, which is the focus of the policy target.

Since we had always run inflation targeting looking out at the medium-term projections, it was never entirely clear to what extent this change was substantive, and to what extent it was (as with many PTA changes) rhetorical – making explicit what was already happening.

Shortly after he took office, Bollard gave a speech in which he tried to explain how he interpreted the new PTA. The speech was much haggled over internally, and so what emerged was pretty carefully considered drafting. The key passage was

The key change in the agreement is that the inflation target has been explicitly defined in terms of “future inflation … on average over the medium term”. This implies that monetary policy should be forward-looking, and avoid getting distracted by transitory fluctuations in the inflation rate. In typical circumstances, we expect to give most attention to the outlook for CPI inflation over the next three or so years. If the outlook for trend inflation over that period is inconsistent with the target, we will adjust the Official Cash Rate. Our intention will be that projected inflation will be comfortably within the target range in the latter half of the three year period.

Note that the “key change” in his view was not the increase in the target – consistent with the notion that the unused portion of the range was just being dropped off – but the “on average over the medium-term wording”. There are no references left to the midpoint of the target range, just a focus on being “comfortably within” the target range when we looked at projections 18 months to three years ahead.

I recall writing an internal paper, probably as part of haggling over this speech, arguing that if anything the new PTA might have given us less (or at least not more) flexibility – a narrower target range balanced against the “on average over the medium-term” wording.

Bollard operated with the same operational autonomy over the OCR as others Governors had. But I think those of us there at the time felt that he had much the same unease about how the Bank had been run – and about the anti-inflation inclinations of key personnel – as the Beehive did. It wasn’t that long after he took office that the OCR was cut by 75 basis points. As always, there were economic arguments that could be made for and against those cuts – at least one seemed reasonable to me at the time – but they proved quite ill-fated. They had to be reversed, and more, although it took too long to do so – and to his credit, at the end of his term, Bollard explicitly acknowledged that the cuts had been unnecessary. The cuts, and the slow reversal of them, set the stage for core inflation increasing to above 3 per cent over the following few years. Without the Policy Targets Agreement change, it would have been a little harder for that particular mistake to have been made.

(In discussions about raising inflation targets, a focus is often on the response of inflation expectations. In a sense, Alan Bollard was gifted a modest “free lunch” – he could stimulate the economy a bit more than otherwise in the short-term – because there was no immediate increase in survey measures of inflation expectations when the target midpoint was raised, perhaps reflecting some sense that – whatever our rhetoric – the 0 to 1 per cent part of the old range had already become something of a dead letter.)

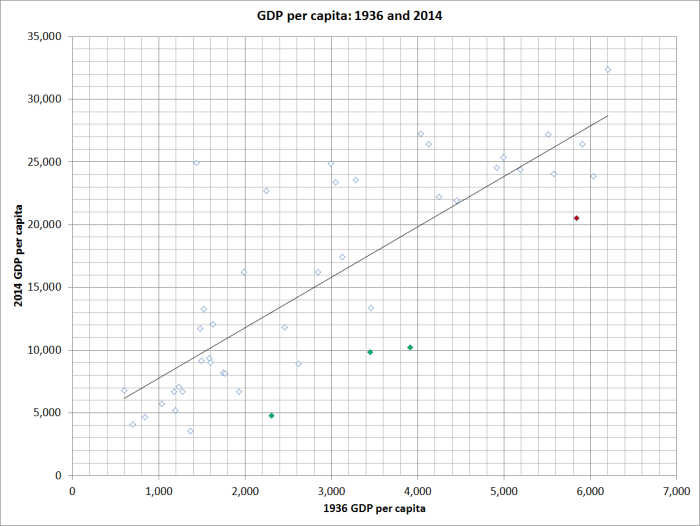

So, as I said, it was politics rather than solid economic analysis that drove the 2002 PTA changes. To the extent that it reflected unease about New Zealand’s economic performance, they were good questions, but the wrong answer. The same could, of course, be said for the desire of Labour, the Greens and New Zealand First to change the Reserve Bank Act now (rather than just the PTA). There are real economic challenges and puzzles around New Zealand’s long-term economic underperformance, but changing purely nominal measures – like the way an inflation (or related) target is specified – is likely to be almost wholly irrelevant to responding to those problems,