It is a glorious day in Wellington, suggesting that summer might really be with us soon. Tempting as it is to just get outside, I had been reading MBIE’s flagship annual report Migration Trends and Outlook 2014/15 and wanted to note (again) a few concerns about the apparent quality of the immigration policy analysis being undertaken by the government’s chief advisory agency in this area.

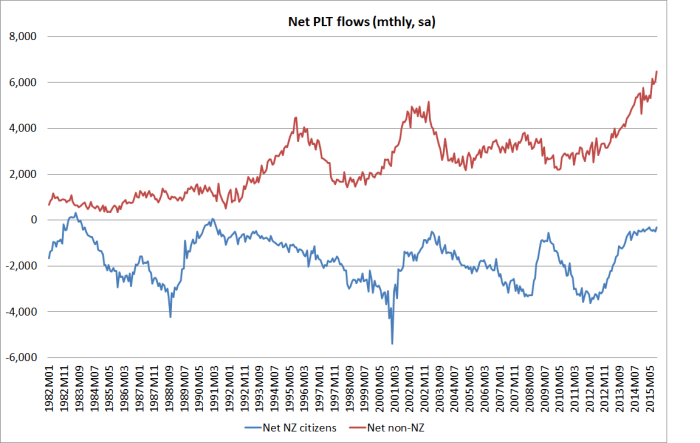

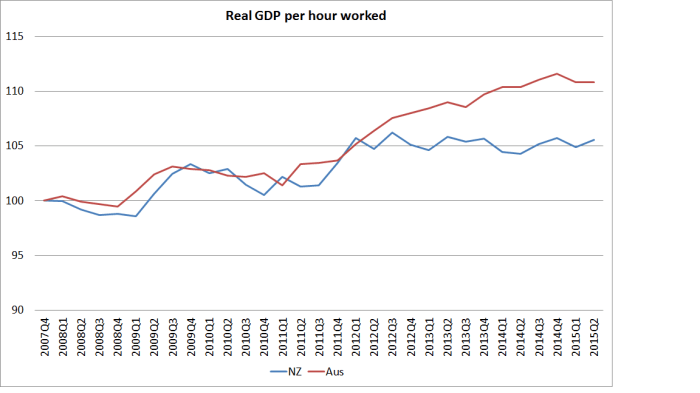

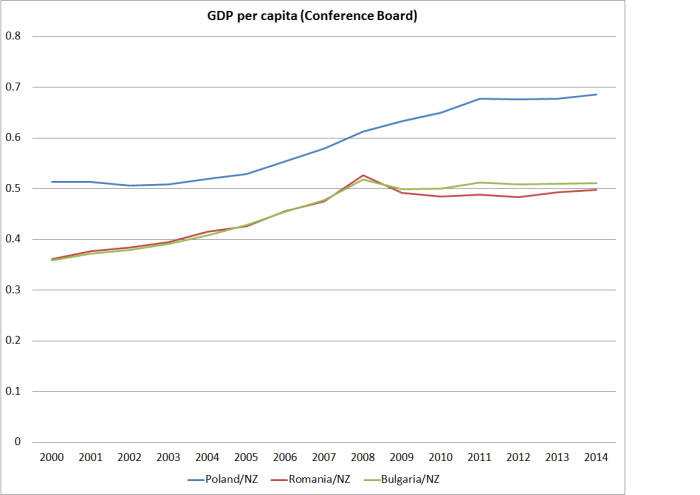

Recall that, in New Zealand, immigration policy is no minor matter – it is one of the largest discretionary structural economic policy interventions undertaken by governments. Each year, on average, we drift a little further behind Australia and the rest of the advanced world. And yet each year we target bringing (permanently) another pool of people equivalent to 1 per cent of the existing population.

Migration Trends and Outlook is not a heavily analytical piece. But it tells the story MBIE wants us to hear about New Zealand’s immigration. And it simply isn’t very convincing.

The report saying that it is aimed at “policy-makers concerned with migration flows and their impacts” and “the wider public with an interest in immigration policy and outcomes”.

So we should take seriously what it says. It begins with this statement:

1.2 Why immigration is important

Immigration helps grow a stronger economy, creates jobs and builds diverse communities. Skilled workers address skill shortages and bring skills and talent that help a wide variety of local firms. Business migrants bring their networks, experience and capital to boost the economy. Visitors and international students bring in significant revenue, with international education and tourism being two of New Zealand’s biggest export-earning sectors.

Internationally, migrants are increasingly mobile, and competition for skilled people in the global labour market is strong. In 2014/15, as in other recent years, the focus of immigration policies continued to be on attracting skilled temporary and permanent migrants to help resolve New Zealand’s labour and skill shortages and to contribute to New Zealand economically.

The “skill shortages” line pervades the entire 66 page document, in a way redolent of a manpower planning exercise from the 1960s. In fact, it reaches a peak in the Conclusion to the entire report where it is asserted that

Like many countries with declining birth rates, an aging population and high emigration of local-born people, New Zealand relies on migrants to fill labour shortages.

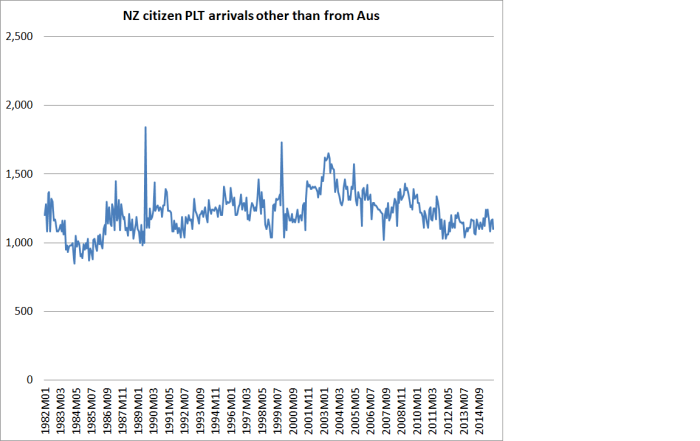

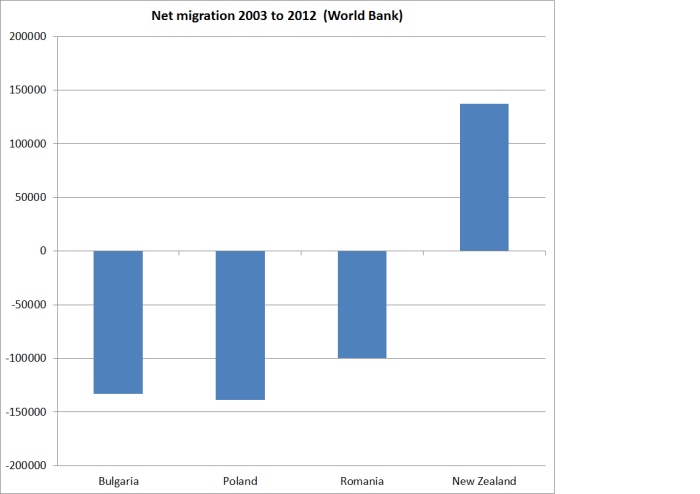

I’ve been trying to work out which countries MBIE has in mind here. For a start, there aren’t that many relatively advanced countries that have an average annual net outflow of their own citizens in excess of 0.5 per cent of the population. And of the countries with large average outflows of their own citizens (various eastern European countries for example), few have large scale inward migration programmes at all. And of countries with large scale inward migration programmes – Canada or Australia for example – I’m not aware of any others that also have large net outflows of their own people.

So the statement seems to be factually false. But perhaps more concerning is the apparent sense that somehow the number of jobs in an economy is independent of the number of people, or the price of the services of those people, and that if it weren’t for the wise actions of a prescient government, the economy really couldn’t cope with (a) New Zealanders pursuing better opportunities abroad, and (b) New Zealanders choosing to have only modest numbers of children.

What I find remarkable in this document, as in other MBIE immigration work I’ve seen, is the absence of any sense of market processes, and how the market might sort these things out. For example, if there are excellent opportunities here which New Zealanders are simply ignoring in their rush to get to Australia, surely we’d expect real wages to increase here? If that happened, some of the opportunities might disappear. Some New Zealanders might change their minds about going to Australia. Some people might regard more training as worthwhile, to better equip themselves for those higher-paying opportunities. Some will switch jobs from less rewarding ones, to the ones where the returns are now higher. Some people might work harder or stay in the workforce longer. But not one of these market mechanisms is even discussed. And this from a key economic agency, implementing the policy of a vaguely centre-right government? Does it not occur to them that “shortages” don’t happen in most markets, and when they do they are usually just a sign that the price has not adjusted. Why does MBIE think that labour is different?

Although MBIE and the government seem to see immigration largely as a labour market phenomenon (“a critical economic enabler”), the price of labour “wages” appears only once in the entire document (purely descriptively). “Price” does not appear at all. In fact, “productivity” and “competition” each appear only once, in neither case in the context of an analytical sentence. “Labour market” does appear repeatedly, but almost always only descriptively. There is simply no sense, anywhere in the document, of a competitive market process at work. If one were being unkind, one might think MBIE saw the role of government as being to ensure that the right pegs were in the right holes.

The “skill shortages” argument has been with us for many decades. I was wryly amused to dip into a book over the weekend which reported the claims of New Zealand employers’ bodies in the 1920s urging high rates of immigration on exactly the same sort of “skill shortage” arguments. You really wonder how countries without large scale immigration programmes managed to survive – let alone to consistently economically outperform New Zealand over many decades.

Immigration advocates have sometimes argued that if only we can attract the cream of the global crop – talent, initiative, ideas – we can lift the productivity of New Zealand as a whole, and that of the pre-existing population as well. It was never very plausible – short of some of global catastrophe, it was never obvious why the cream would now want to come to New Zealand – a pleasant spot to be sure, but small and very remote, and not at the leading edge of very much. There is periodic talk of the transformative powers of immigrants in Silicon Valley, but even if it were true there, why would it be likely (on the balance of probabilities) to work here? We are small and distant. San Francisco is neither. And we have universities that, in most fields, are mediocre at best. We are fooling ourselves – or rather our governments seem to keep trying to fool us – if we believe that plausible immigration (volume, type of people, or whatever) is the answer to New Zealand’s economic challenges. There is no sign it has been in the last 100 years, and the boosters – MBIE chief among them – offer no reason to think that is about to change. We have to make our own future – as most successful countries in the past have done. If we do, perhaps able people will be clamouring to join us and we can (or not) take the pick of the crop. For the present, it still seems more likely that rational New Zealanders will choose to leave for Australia whenever they can, although it is harder to do so than it was previously.

I’ve written previously about the relatively low-skilled nature of even most of those being granted residence as Skilled Migrants over recent years. The table below (from the MBIE report) updates that for 2014/15. And recall that these are the principal applicants in the Skilled Migrant category – ie the most skilled of our migrants. They make up only around a quarter of our annual residence approvals. Not all of the others will be less skilled, but on average they will be. I don’t know about you, but this list does not suggest that our immigration programme is functioning as any sort of medium-term “critical economic enabler” (to use one of MBIE’s own phrases).

| Main occupations for Skilled Migrant Category principal applicants, 2014/15 | ||

| Occupation | 2014/15 | |

| Number | % | |

| Chef | 699 | 7.2% |

| Registered Nurse (Aged Care) | 607 | 6.2% |

| Retail Manager (General) | 462 | 4.7% |

| Cafe or Restaurant Manager | 389 | 4.0% |

| ICT Customer Support Officer | 282 | 2.9% |

| Developer Programmer | 209 | 2.1% |

| ICT Support Technicians nec | 205 | 2.1% |

| Software Engineer | 147 | 1.5% |

| Accountant (General) | 138 | 1.4% |

| Early Childhood (Pre-primary School) Teacher | 127 | 1.3% |

| Marketing Specialist | 124 | 1.3% |

| Dairy Cattle Farmer | 123 | 1.3% |

| Carpenter | 122 | 1.3% |

| Electrician (General) | 111 | 1.1% |

| Office Manager | 106 | 1.1% |

| Baker | 105 | 1.1% |

| Program or Project Administrator | 97 | 1.0% |

| Software Tester | 95 | 1.0% |

| Sales and Marketing Manager | 94 | 1.0% |

I noted the other day, that the residence approvals target has not been met for the last five years (the target is 45000 to 50000 per annum, and approvals have lagged a bit below 45000 each year). That raises some questions about even the design of our immigration programme. I’ve always tended to work on the assumption that since most of the world is much poorer than we are, it should never be a problem finding enough immigrants if we wanted them – even notionally “skilled” ones. Returns to labour in New Zealand are higher than anywhere in Africa, Latin America, the Pacific, or most of Asia. There are plenty of English speakers who could pass health and security tests. So how come we can’t fill our targets with suitably “skilled” people – especially as the skills threshold seems depressingly low?

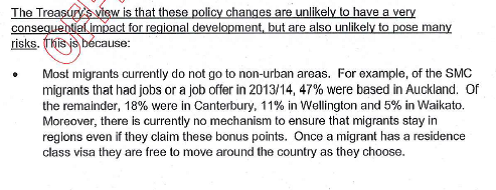

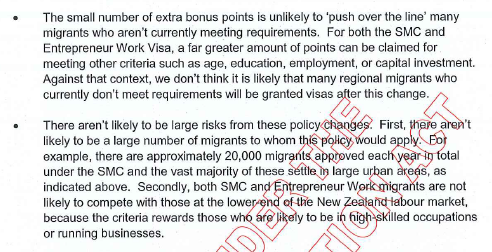

I wonder if it is partly because most residence approvals are now granted to people already living in New Zealand (around 70 per cent) – that is typically people here on a work visa, or a study visa. The logic is apparently that people adjust more easily if they are already familiar with New Zealand. So in applying under the skilled migrant category you get points for having a job or confirmed job offer. 92 per cent of successful applicants got points that way. You also get points for a job outside Auckland, even though Auckland is the fastest-growing part of our economy – just over half of all those with jobs/offers claimed points for jobs out of Auckland.

But it is expensive to come to New Zealand – particularly for people relocating a family here. And it is hard to effectively job-search from abroad. And we impose an additional cost by rewarding people who get job offers in the less productive parts of the country (with fewer alternative future opportunities). Personally, I think our immigration policy is pretty deeply flawed, but if our governments are serious about wanting lots of skilled migrants shouldn’t we think about putting fewer roadblocks in the path of any able person who wants to come? There seems to be something wrong with the fact that a country with still relatively high returns to labour can’t manage to fill its immigration target (despite alleged “skill shortages”), even by taking such a pool of rather dubiously “skilled”people. 10000 a year (the number of skilled migrant principal applicant granted approval) simply isn’t that many in world terms – we really should be able to do better than having the four most common occupations of our skilled migrants being chefs, aged care nurses, retail managers and café and restaurant managers.

Perhaps the continued emphasis on skill shortages is a sign that MBIE has largely given up on the other channels by which immigration might boost “the prosperity and wellbeing of New Zealanders” [the phrase from MBIE’s own mission statement]? But even if so, the “skill shortages” argument – for the sorts of people New Zealand is mostly importing – is pretty intellectually slipshod. In addition to the points I noted earlier, the MBIE document is also devoid of any macroeconomics. It has long been pretty common ground among New Zealand macroeconomists that, whatever the possible long-term effect of immigration, in the short-term immigrants add more to demand than they do to supply. The Reserve Bank’s own research shows it. But what that means is that even though an individual immigrant might relieve an individual employer’s “skill shortage”, in aggregate an increase in immigration increases the pressure on the labour market as a whole. Resource pressures are intensified and not eased. If the knowledge transfer and productivity stories carried much weight now for New Zealand – as perhaps they may have in the 19th century – that might be fine. But there is no evidence of that channel having worked, and no real sign of that changing soon. And yet if our immigration policy is supposed to ease skill shortages it is almost doomed to fail by construction.

We deserve rather a better quality of analysis from a large public agency paid to provide high quality economic advice on immigration and economic performance issues. I hope that when the Cabinet has been reviewing the residence approvals target recently they have been more willing to ask some hard questions about just what is being achieved by our immigration programme than has been evident to date.