The Treasury this morning hosted a guest lecture on the merits (or otherwise) of a Fiscal Council, hosted by the acting Secretary to the Treasury, Struan Little.

A Fiscal Council in this context is something quite different from the sort of state-funded policy costings office that many of the New Zealand political parties seem to be gravitating towards thinking would be good idea (more state funding, under the guise of something in the public interest, so why should we be surprised). Over the years I’ve written consistently sceptically about the policy costings unit idea, and was only reinforced in that view by my involvement last year in the contretemps over the costings of National’s proposed foreign buyers tax.

The general idea of a Fiscal Council is to have an independent expert-led small agency that provides independent and non-partisan analysis, research and advice on aggregate fiscal policy, aiming to improve the overall quality of debate on fiscal policy issues and, so it is hoped, improve fiscal policy itself. Such bodies have become flavour of the decade over the last 15 years or so. Fiscal councils are particularly common in Europe, where the macroeconomic issues are generally rather different: countries in the euro-area not only give up the option of monetary policy for national cyclical stabilisation (leaving any such national countercyclical activity to fiscal policy), but are also subject, loosely as it may be, to European Union rules.

The idea of establishing a New Zealand fiscal council has been championed by the OECD (but there have been other advocates, including a report from a former top IMF fiscal official done for The Treasury a decade or so ago, and the New Zealand Initiative). I also tended to be somewhat sympathetic (but see below).

The speaker at this morning’s lecture was Sebastian Barnes, a (British) mid-level manager in the OECD’s Economics Department, and (while working for the OECD) a former long-serving member (and then chair) of the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council (IFAC), that had been set up in 2011 in the wake of the Irish financial and fiscal crises of the previous few years.

My impression, from a distance, of the IFAC had been fairly positive over the years, and nothing Barnes said this morning shifted that sense. IFAC is a pretty lean body (apparently costing about EUR1 million per annum), with five part-time council members (a mix of academics and people with more of a policy background), and a secretariat of five fulltime economists and one administrator (they apparently share premises, and admin support with the main national economic research institute). If you look at the current council, three of the five members seemed to be non-Irish (two UK-based and one Italian – a retired IMF official who used to be the desk economist for Ireland).

Barnes spoke very positively about the Irish IFAC. That wasn’t exactly surprising – he’d spent 10 years on the Council, was present at its creation, and works for the OECD, which has called for New Zealand to set up a Fiscal Council – but his comments and experiences were interesting. For a small entity, they are pretty active and publish quite a few regular reports each year, as well as more occasional (but not infrequent) research. Barnes noted that the role of IFAC was threefold: monitoring compliance with the fiscal framework, improving fiscal and economic analysis in Ireland, and promoting informed debate on fiscal issues (and not just among technocrats and politicians).

He claimed (and I have no reason to doubt him) that IFAC had become a fairly respected and well-regarded entity on the Irish scene, and that (for example) it had established a strong reputation with the media as a credible analytical agency and a clear communicator. Barnes reckoned IFAC’s presence had helped strengthen parliamentary oversight on fiscal policy issues. One thing that he was at pains to stresses is that IFAC focuses on analysis and avoids getting into normative debates. Here he seemed to be primarily referring to choices around raising taxes or reducing spending (as ways to maintain overall fiscal balance and moderate debt), let alone to specific tax policy or (say) pensions spending. There is, it seems, quite enough to do in deepening understanding of the fiscal arrangements and highlighting risks around fiscal policy becoming pro-cyclical, a big issue for Ireland leading up to 2007. It is worth noting that Ireland now has some very distinctive issues, notably an abundance of tax revenue from foreign multi-nationals (and a big budget surplus), of the sort that may (or may not) prove particularly sustainable, and where the associated tax bases are not always hugely well understood.

It is difficult to see that the IFAC has done any particular harm. Perhaps it has even done some good for overall economic policy in Ireland. It doesn’t appear to have become politicised, it has maintained a clear sense of an expert-led analytical and advisory body. And it hasn’t cost the Irish taxpayer very much at all.

But it is still rather hard to pin down quite what useful difference fiscal councils, there or elsewhere, have made, and thus whether New Zealand really should regard the establishment of one as a medium-term priority. Barnes did note that a very visible effect of establishing fiscal councils had been that more people were now working on fiscal policy issues (he reckoned at least 100 more across Europe) and argued that fiscal policy issues had tended to be under-researched, especially relative to monetary policy. He several times referred to their inspiration as being expert-led research-oriented central banks. More research isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but…

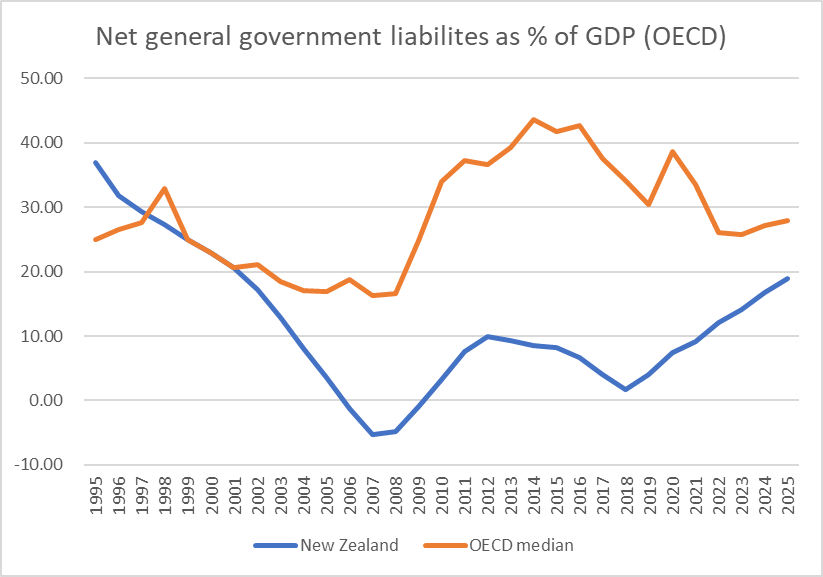

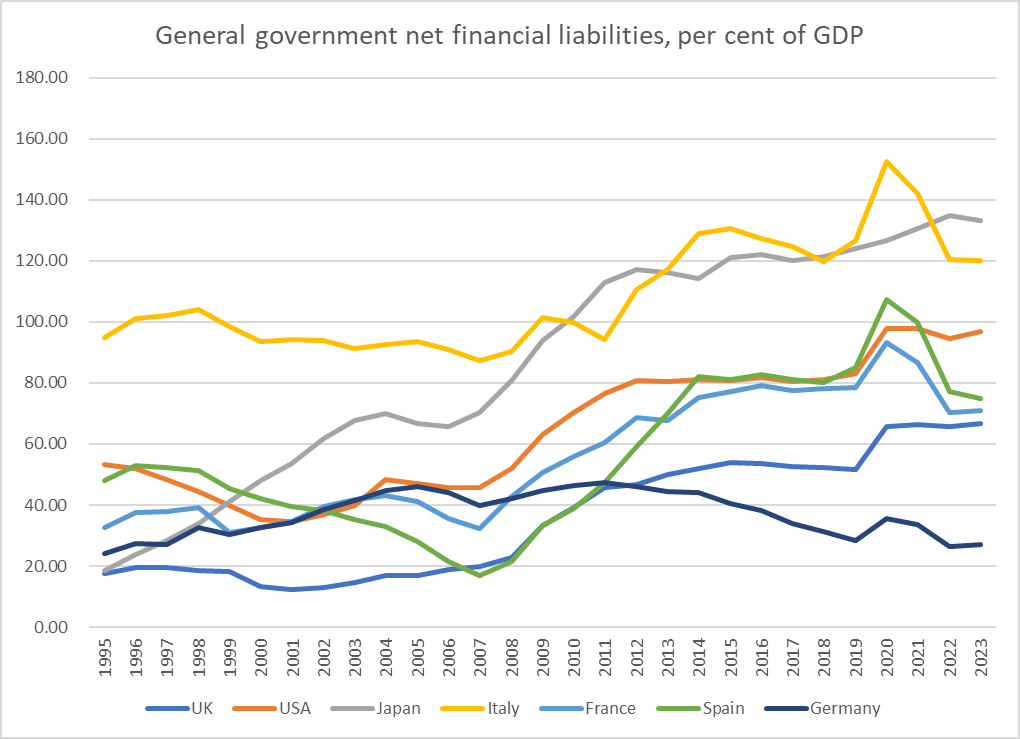

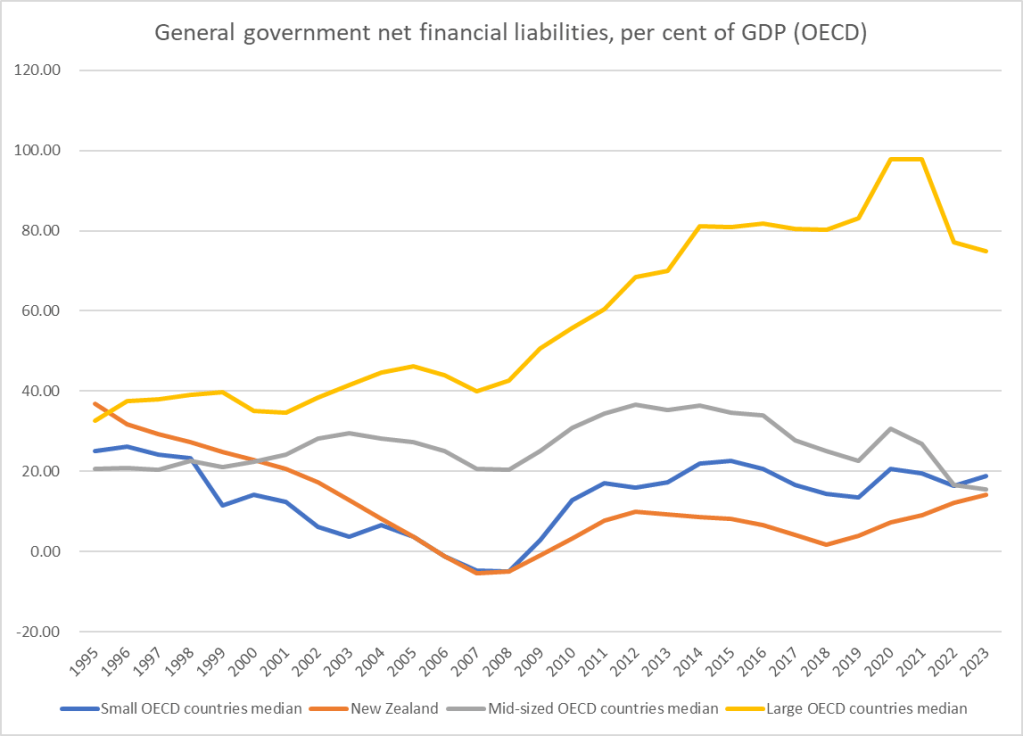

I posed a question, noting that across the OECD there had been a proliferation of fiscal councils and yet it wasn’t obvious that overall fiscal management was getting better (he’d opened his talk with a multi-country chart of gross debt as a share of GDP, and if not every country had gotten worse over the decades, the upward trend (dominated by large countries) was pretty clear). Perhaps things were improving relative to a counterfactual (not directly observable) or perhaps fiscal councils might be more in the nature of a nice-to-have, a luxury consumption item – and good for the employment of macroeconomists and public finance people – rather than an effective contributor to better fiscal policies?

His (honest) answer was that we “can’t really tell”, but that he thought some had had “some incremental impact”, while going on to note that some of the better-regarded ones were in places (like Netherlands, Denmark, and Sweden) which had long managed themselves fairly well anyway. Perhaps a decent Fiscal Council was then a common output of a wider disciplined approach to good government and effective fiscal management? As for Ireland, I was struck the other day by a feature article in the FT about Ireland’s fiscal challenges (those big surpluses from the corporate tax revenue), in which numerous Irish commentators were quoted/mentioned, but there was no reference to IFAC or its analysis at all.

It was an interesting presentation, but if it was the best case for a Fiscal Council here (and it should have been given his OECD and IFAC background) I didn’t find it very persuasive. It wasn’t helped by the New Zealand experience of the last decade, where (a) the central bank has become anything but expert-led and produces little serious research or analysis of its own (for all its limitations, Treasury is now producing more), and (b) a Productivity Commission was set up, with a vision of being expert-led, and has now disappeared again, amid a sense (well-justified in my view) that the previous government had substantially degraded it (and to be clear this isn’t a partisan critique – active partisan seem to have been appointed by this government to several boards which should be known for being highly non-partisan). How optimistic could one be that a Fiscal Council could avoid being quickly degraded and politicised, in the New Zealand as we now find it? And do we really think that our fiscal challenges – as we drift towards being a normal OECD country in that regard – have to do with lack of sufficient analysis (official or public)?

A decade ago I had a somewhat different view. About the time I was leaving the Reserve Bank I wrote a discussion note for my then colleagues, prompted by a recent visit from US academic economist Ross Levine who was championing an arms-length monitoring body for banking regulation, suggesting that perhaps there was a case for a Macro Council, providing arms-length and independent analysis, research and review around fiscal policy, monetary policy, and financial regulation. I put the discusssion note on this blog back in its early days.

These days I’m pretty deeply ambivalent. While such a body might, perhaps, play a useful role (mostly as luxury consumption item, but if one is wealthy and successful there is nothing wrong with luxury consumption) in enriching debate/analysis in a successful and well-governed New Zealand, if I was a Minister of Finance seriously interested in much better institutions for economic policy etc in New Zealand, it isn’t where I would start. Whatever really able people are available, whatever financial resources can be spared, which be much better used in seeking to overhaul and get to (or in some case back to) real and sustained analytical and policy expertise. If I had in mind particularly the Reserve Bank, it is far from being the only economic institution with diminished capabilities (and perhaps limited demand for something better from successive ministers). And it is difficult to see how an effective Fiscal Council, let alone a Macro one, would be appointed (and able composition maintained). We have very few academics working in the area, no non-partisan research institutes, and while there are partisan people with real expertise attempting to tap them is just a recipe for repeated games of partisanship in appointments. And while I quite like the Irish use of foreign expertise, the realistic pool is limited to Australia (travel distance still matters a lot) and that pool itself doesn’t seem deep). And Ireland doesn’t need to stock a quality MPC.

It was an interesting presentation, it was good of Treasury to host it, but count me unconvinced.