For a long time I’ve been a strong supporter of central bank transparency about stuff a central bank actually knows something about, but a sceptic of the faux transparency of publishing stuff a central bank really knows very little about. In the former category, one might think of the background papers going to the MPC (by aiming deliberately low I once got them out of the Bank for a forecast round 10 years previously, but good luck if you asked now for the papers around the 2020 and 2021 decisionmaking, let alone those from six months ago). In the latter category I primarily had in mind medium-term macroeconomic forecasts, including endogenous forecasts for the OCR. Sure, the numbers are mostly put together fairly honestly, but in truth (and this isn’t a criticism, more a description of the limitations of human knowledge) central banks just don’t know very much about the future, especially a couple of years ahead. In principle, an OCR forecast now for the end of 2026 would be drawing on forecasts for inflation pressures well out into 2028. Forecasting 2024 or 2025 remains a considerable challenge.

But my criticisms there have typically been about the hubris or delusion involved in thinking one could add meaningful value re where things might be a couple of years hence. In fact, I was rereading this morning an old piece I used at a BIS conference years ago on such issues. But I tended to be relatively more relaxed about near-term forecasts, for (say) the next quarter or two, included the associated guidance on likely policy. If one might still be sceptical about just how good central banks might be at nowcasting or near-term forecasting (a) they do have more resource to throw at the issue than any other forecaster, and b) they should at very least know a little more than we otherwise do about their own reaction functions (ie how they might react to any given set of economic/inflation data). That might be so whether one had in mind explicit near-term OCR forecasts (to the second decimal place) as the Reserve Bank does, or just “bias statements” of the sort pretty much all central banks tend to engage in.

Here in New Zealand, even with some new and (apparently) improved external membership of the MPC, the last six months don’t score very well even on that count.

It was less than five months ago (22 May in fact) when the MPC released a Monetary Policy Statement indicating, in their forecast track, that there was a bit better than even chance that the next warranted move in the OCR would be an increase this year (to be consistent with this track, probably in August).

Their associated communications (which I’ve written about previously) was so at-sea that they tried to deny the implications of their own chosen track (the chief economist even tried to blame it on the tools, rather than the MPC of which he was a part).

Within six weeks, (without a new full set of forecasts, and in the absence on holiday of the chief economist), the MPC had flipped to a dovish stance. This was how I illustrated it at the time

And on this occasion they more or less did follow through. There wasn’t any huge inconsistency between their July and August statements (and the associated 25 basis point cut in the OCR).

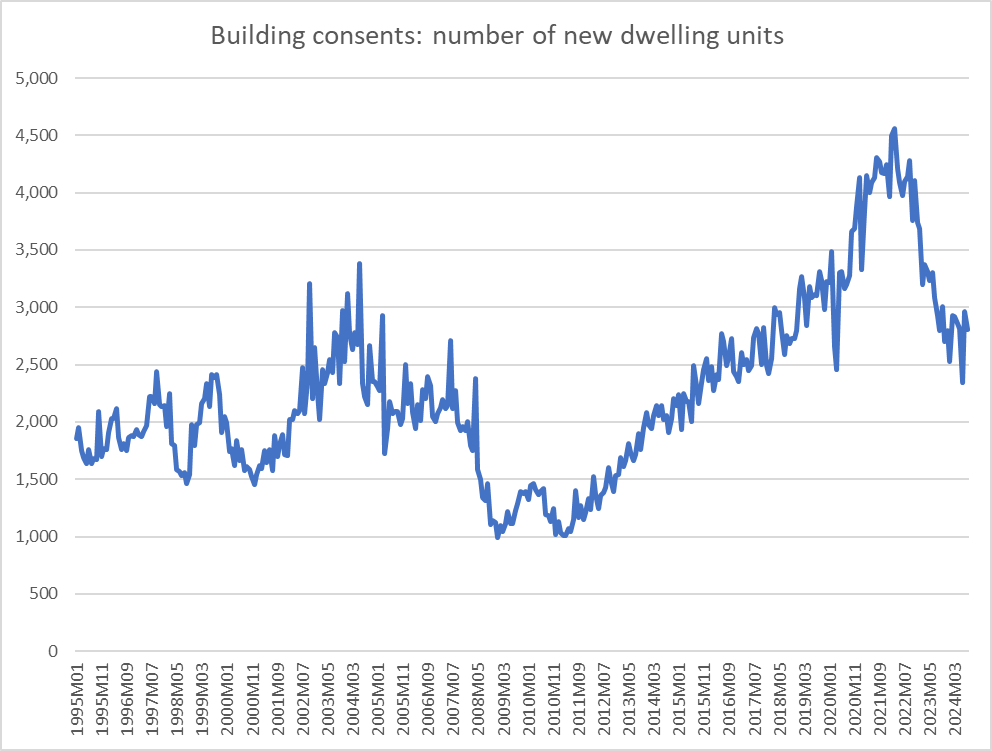

But this was the forecast track in the August MPS, published only six weeks ago

That forecast track was exactly consistent (weight by days) with 25 basis point cuts in October and November, such that it was clearly intended by the MPC as specific forward guidance. It looks as if they envisaged another 25 basis point cut in February such that by then the OCR would have been lowered to 4.5 per cent.

And yet yesterday we saw a 50 basis point cut, and a fairly high degree of confidence among market economists that another 50 points will follow next month. One can argue that there wasn’t a clear direct signal of that from the MPC, although when you put a big headline in the “minutes”, and explicit statements that a) inflation is expected to “remain” around the target midpoint, and b) that an OCR of 4.75 per cent is still “restrictive”, it doesn’t take much guessing to see what they had in mind yesterday (especially with the three month MPC summer holiday coming up).

Now, as it happens, I think yesterday’s OCR cut was most likely to right call in substantive macroeconomic terms (and still think we are probably heading towards 2.5 per cent by the second half of next year). But that isn’t the issue for this post. Rather the point was nicely summed up by a journalist’s tweet yesterday

Which is a pretty damning indictment, of a committee whose claims to exercise such great discretionary power is that they are technically expert and have some reliable/predictable idea of what they are doing. And that simply isn’t obvious at present.

No one particularly minds when central banks change their mind when there is some significant exogenous shock, the size or timing of which they could not reasonably have anticipated. But it is far from clear that anything very much has changed about the economic backdrop since May (no really big data surprises on GDP or unemployment, and confidence measures seem to have bounced around a bit without leaving us in a lot different place than in early May, let alone August). Instead, the expert committee, drawing on its staff, seem simply to have gotten things very wrong, and to have seriously misread the extent of the disinflation that was already well in train (or at least so they assume, having anticipated yesterday the CPI numbers out next week). It doesn’t seem so different (though probably less severe) than the mistake they made in 2020/21 and even early 2022.

If the MPC really can’t do better than that there are two options. Either they aren’t the men and women for the job (in several cases that seems quite likely) or they should stop just injecting random noise purporting to be expert judgement by publishing forward tracks and indications of what might happen next. And, of course, there is no indication in any of the published sets of minutes from May to now of any robust debate or disagreement among MPC members, which is simply additionally damning: they all went along with each of the flip flops and inconsistencies through time, with no indication that any of them were applying the intellectual energy and analytical grunt to contest and challenge whatever view was coming from staff or management. I’ve long argued for much more personal accountability for MPC members – the risk has always just been that individuals (whether inexpert internals or the externals) would just free-ride, go along for the status, the fee, the addition to the CV, while adding little, and not bearing any consequences when the overall MPC does poorly. Management hates the idea of an open contest of ideas – has ever since reform models started being explored a decade ago – and one of their worries was of a “cacophony” of voices, in which truth would be obscured. It was never a compelling argument – other central banks manage, and it was a clearly an argument that reflected mostly management self-interest – but the experience of the last six months highlights again just how little “truth” or knowledge there is in anything much the MPC says beyond the specific OCR adjustment on a specific day. An open (but respectful) contest of ideas, exploration of alternative models, could hardly be worse than what’s been on offer again this year.