I picked up The Post this morning and in an article about some of the fiscal challenges governing parties may face came across this line about the latest pay offer to secondary teachers. The journalist might have been channelling the Beehive with his line that “it’s a very good offer”, “the union would be mad to turn it down”, and (most striking to an economist) “remarkably the pay hike is more than double that of the rate of inflation”.

Knowing it was a multi-year settlement, well after the expiry of another multi-year collective, that was really a bit much: apples for oranges comparisons sprang to mind. So I went and tracked down some numbers, and then some more numbers. The first round were in a Twitter thread here.

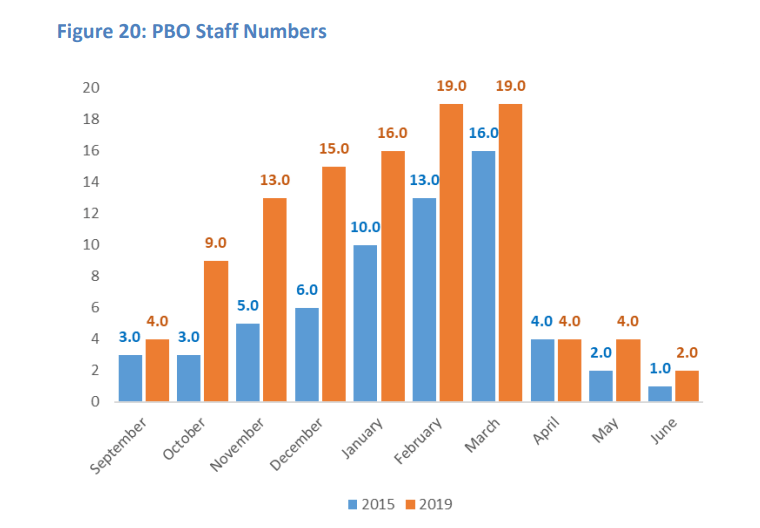

Over time one normally expects to see real (inflation-adjusted) wages rising. In New Zealand, as in most places, they were last decade. But times have been tough since. In this chart I’ve used the best (stratified) measure of private sector wages rates, deflated by the CPI.

In the last couple of years there has been a significant setback. On this measure of real wages, as at Q2 this year real wages were no higher than they had been four years earlier. There are probably several factors at play: prices (inflation) often adjust faster than wages, especially when there is an inflation shock out of blue, forecast by almost no one. But – despite the record low unemployment rate – there are also other dragging factors; notably the fact that there seems to have been very little economywide productivity growth over the last several years, and the terms of trade have also fallen quite a bit. There are no mechanical linkages from any of these influences to wage rates, but in many ways the recent poor performance of real wages might not be considered too surprising.

But even so, on average, New Zealand real wages rates last quarter were still about 7.5 per cent above where they’d been at the start of the period shown.

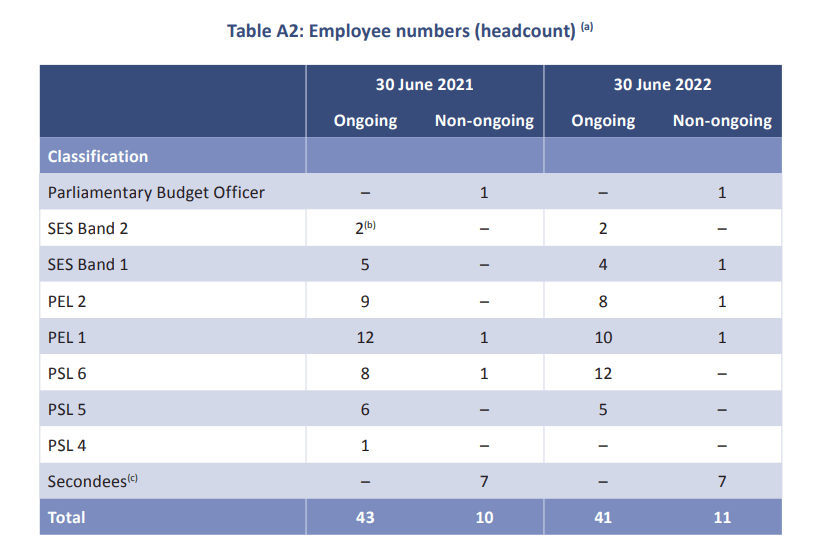

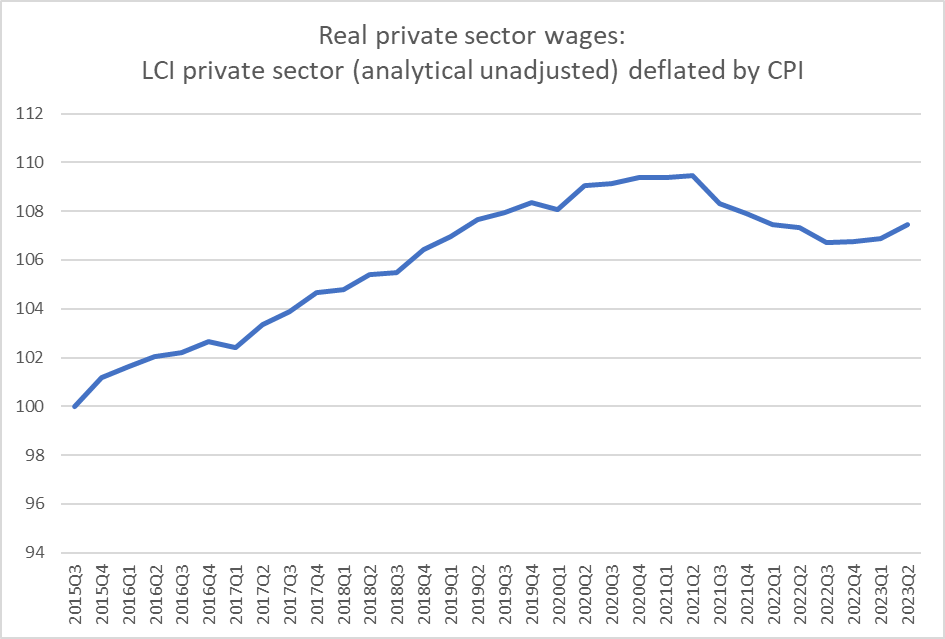

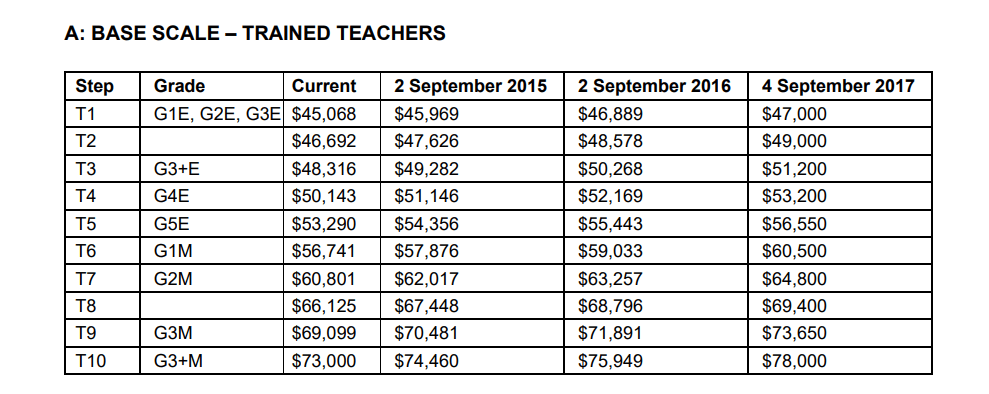

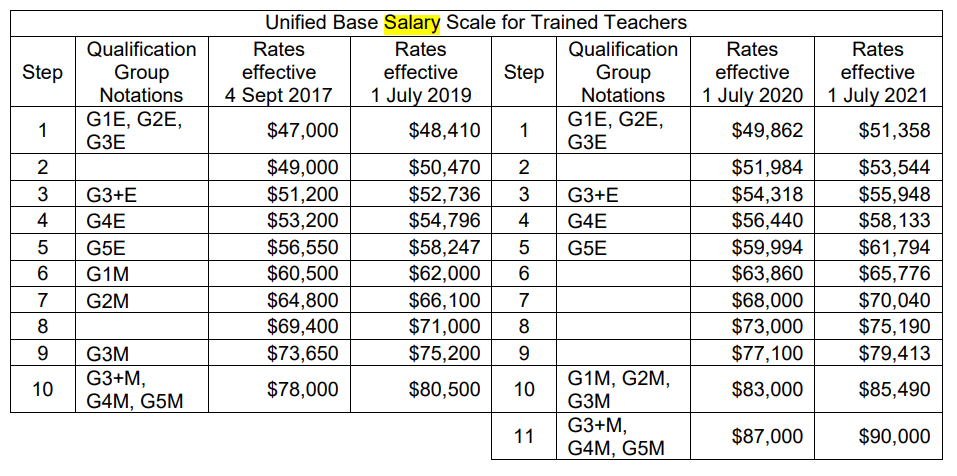

Why did I choose that period? Because back in the dark woebegone (or so the left and the teacher unions would have it) days of the Key government the second most recent secondary teachers’ collective employment was signed (October 2015). Backdated a few weeks, the teachers got a payrise, and an agreement to a couple more pay rises over the following couple of years. Multi-year nominal agreements make some sense (keeping down negotiating costs etc) when inflation is low and stable.

In July 2019 another three year agreement was signed, this time by the Labour government.

You can see the first column of that table is the final column of the previous table. You can also see the new top of scale step added to the table.

The latest offer by the government is for increase of 6 per cent backdated a few week to 3 July, another 4 per cent next April, and a final 3.9 per cent on 1 December next year. I’m not clear whether the proposed agreement would be for two or three years, but these are the wage increases offered. The July 2023 increase appears to represent the first salary increase since July 2021, in which period inflation has run far away that earlier negotiators will have expected. As it happens, the labour market has also been very tight in that time.

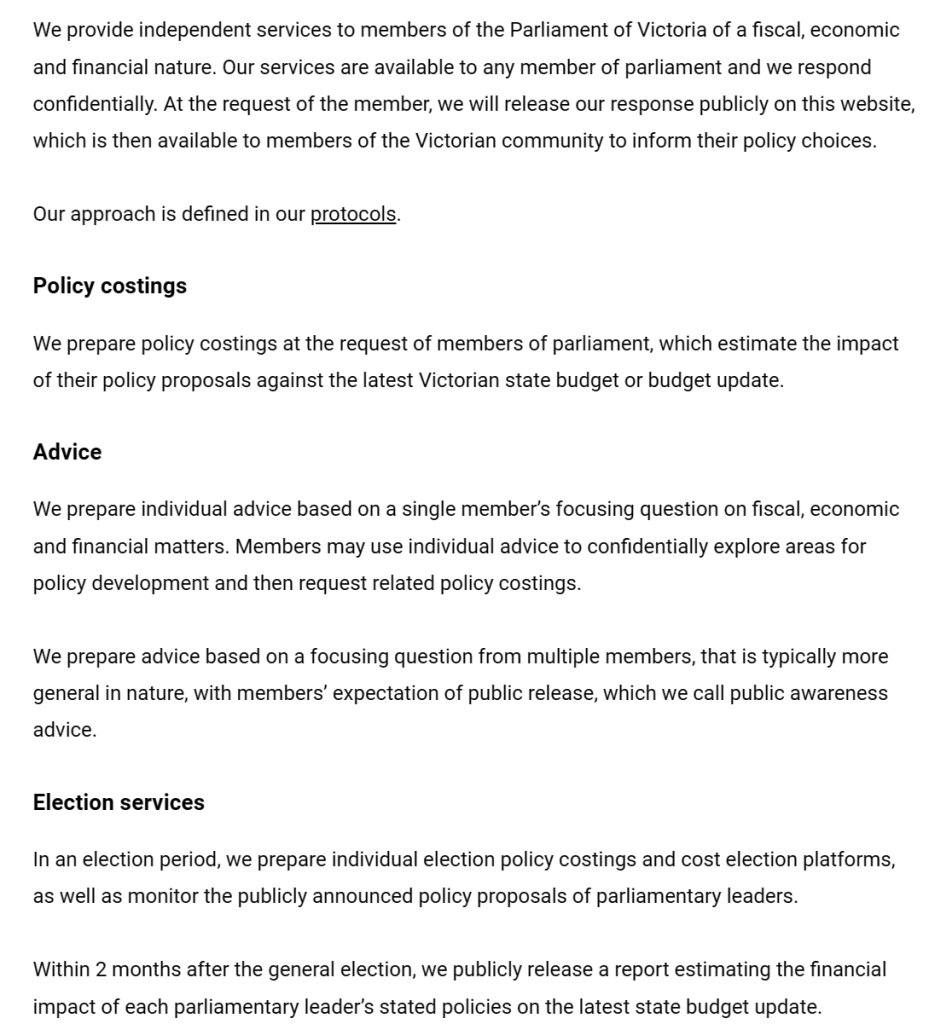

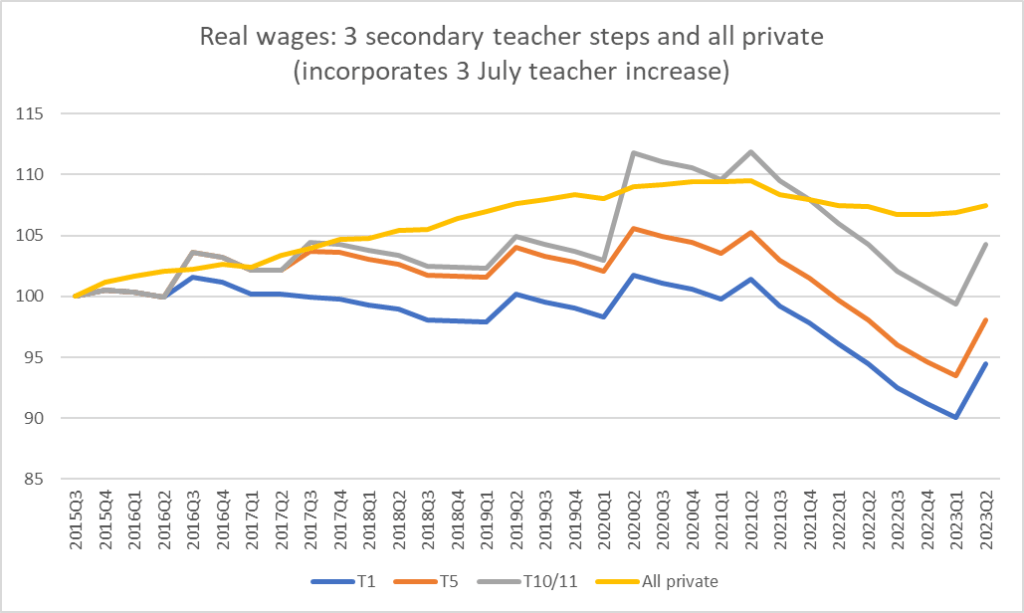

What I was curious about was how teachers were doing (a) relative to the CPI, and b) relative to private sector wages (why private sector? Because they tend to move a bit more flexibly in response to economic conditions rather than political imperatives.)

The secondary teachers’ scale now has 11 steps. For simplicity, I looked at just bottom one (T1), step 5 (T5), and the top step (was T10, now 11). Incorporating the 3 July increase teachers are being offered this is how real teacher salaries from 2015 to now compare with the movement in private sector real wages over the same period.

All three steps leave teachers right now behind the private sector as a whole, with only the effect of that new top step added in 2019 bringing that group of teachers somewhere close to the average private sector movement over those eight years.

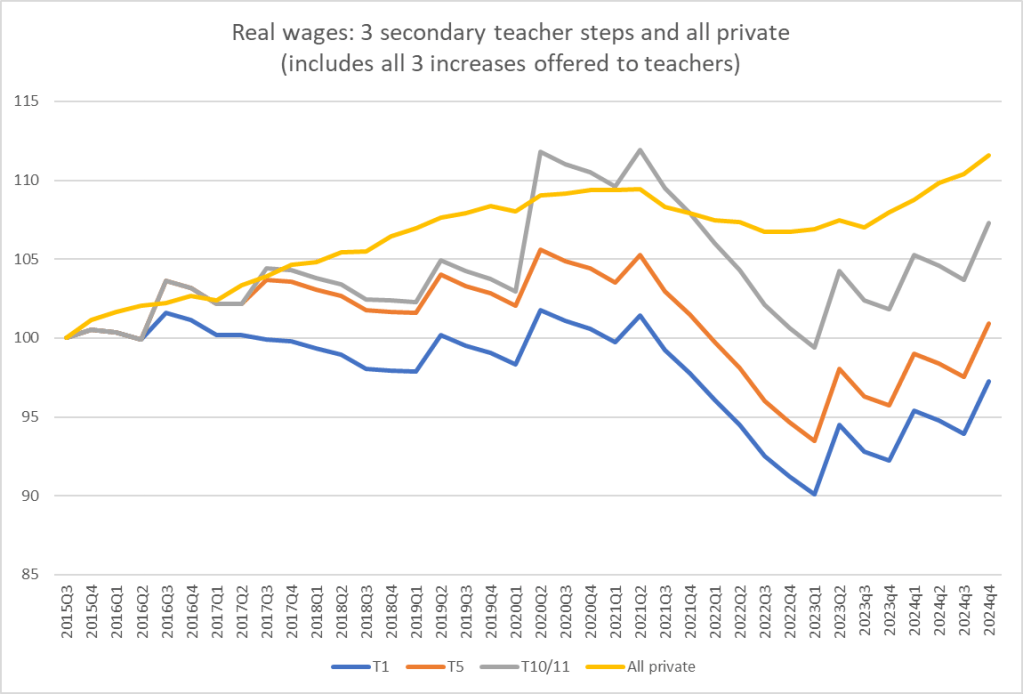

But, of course, the offer includes two more pay increases for secondary teachers. Those are known, and if the offer is accepted, guaranteed. We don’t know what the inflation rate will be over that period (or what inflation rate either the teachers or the government had in mind) but the Reserve Bank is responsible for inflation and they publish quarterly forecasts. The most recent ones were published in the May Monetary Policy Statement, and my sense is that they may be a little low. But in the next chart I’ve used them to deflate the teacher pay rises.

We also don’t know what will happen to private wages, but again the Reserve Bank publishes forecasts (they publish forecasts for the private sector LCI, but I’ve adjusted them to a private sector LCI (analytical unadjusted) using the recent gap between the two series. The Bank expects quite a bit of growth in private sector real wages in the next 18 months.

Over 9 years, on these forecasts, private sector real wages would have risen by 11.6 per cent, but the real wage rate for starting teachers will have fallen, and that for the middle step hardly have changed at all. Even that new top step included in 2019 doesn’t bring the real increase close to that for the average private sector job.

(There is a one-off lump sum payment as part of the offer, but that is best seen as “compensation” for teachers having been caught under a multi-year agreement with hugely high unexpected inflation – the direct responsibility after all of a government agency. It doesn’t affect real wages looking ahead, or thus recruitment/retention choices/challenges.)

Of course, it is up to the teachers whether or not to accept the offer. Perhaps on average it replicates what a market process would eventually have thrown up, and recruitment and retention will no longer be a challenge for schools once this agreement is in place. Or not.

But it is a little curious to contemplate the sight of a left-wing government, of a party long quite closely aligned with teacher unions, asking teachers to agree to significant real wage cuts relative to what was envisaged when the previous agreement was signed in 2019. Critics of the declining quality of the education system might suggest that such an outcome as only fair and reasonable, but I rather doubt that is the message the former and current Labour Ministers of Education have in mind.

And in a high-performing education system you probably wouldn’t expect to see secondary teaching real wages falling, and falling behind those of the private sector as a whole.

But with only one child left in school, if the offer ends the strikes for the last 18 months of our direct exposure to the system I guess that will count as some small mercy.

PS: One slight consolation of the current outbreak of inflation is the reminder for a new generation of just why high and unpredictable inflation is a bad thing. Not only do multi-year agreements become a lottery, but there is all that money illusion that leads people to see a 14 per cent one-off increase as large or generous,