Or to give the book its full title, The Money Illusion: Market Monetarism, the Great Recession and the Future of Monetary Policy.

I was engrossed in the 2008/09 recession – and the associated financial crises – at the time it happened, as an official at the New Zealand Treasury, and it must have been very early in the piece that I started reading Professor Scott Sumner’s then new blog, also The Money Illusion. I’m not a regular reader now, but found much of what Sumner had to say about the conduct of monetary policy – mostly in the US – stimulating and thought-provoking, even (perhaps especially) when I didn’t end up agreeing. So I was keen buyer when his 400 page book appeared.

It is an interesting mixture of a book – partly textbook, partly personal intellectual autobiography, and partly a tract championing a different approach to policy (and history). It would be well worth reading for anyone interested in monetary policy, with a particular focus on the recession of 2008/09 and it aftermath, and possible reforms for the future. Were I an academic teaching a monetary economics class I’d encourage all my students to read it (and have commended it to my economics-student son), not as replacement for a textbook but as a practically-oriented complement to it.

I usually read books of this sort with a pen in hand. But flicking through the book again I see that the pen was hardly deployed at all in the first 60 per cent of the book, which is a really clear and useful introduction to how the monetary system works, through a slightly different lens than most will be used to. If I didn’t agree with it all – and there were a few straw men tackled – people coming to grips with the system and concepts and history will almost inevitably see things more clearly for having read it. It is an achievement in its own right.

The second part of the book is focused much more on the policies adopted, mostly by the Fed, in 2008/09, and on the way ahead (bearing in mind that the big was largely finished before Covid, although I doubt the thrust of Sumner’s arguments would have been much changed by the experience of the last 18 months). And it is there I start to differ (and thus have lots of marginal notes).

It isn’t, I think, that we differ that much on how the economy works (or even how monetary policy works). Like Sumner I’m a champion of the potency of monetary policy. It can’t make countries rich, or solve things like New Zealand’s decades-long productivity failure, but it can – and should – do all it can to keep the economy as fully-employed as (labour market regulation etc makes) possible consistent with keeping inflation in check. It really matters, given the pervasiveness of sticky wages and prices in the economy. Sumner’s previous book, on the US experience of the Great Depression, was a really nice illustration of both the potency of monetary policy, and the way that misguided regulatory interventions (in that case much of the New Deal) can mess up economic performance.

And I’d also endorse two of his specific criticisms of choices the Fed made in 2008.

The first was the failure to cut official interest rates at the FOMC meeting a couple of days after the Lehmans failure. I think everyone – including Bernanke – now recognises that it was a mistake, but it really was an almost incomprehensible one. The justification was that the FOMC saw the risks of higher inflation as balancing the risks of lower growth. Now, as I noted in my post yesterday, headline inflation in September 208 was high – oil price effects mostly – but it is still hard to see how smart people could have reached the conclusion that a cut in the Fed funds rates was more risky than sitting tight. There was, for example, nothing disconcerting about the medium-term inflation outlook revealed in the breakevens in the government bond market (and by this time the Fed had already cut the Fed funds rate by quite a lot over the previous year. This is, of course, consistent with one of Sumner’s themes: central banks really should be taking more of a lead from market-price indications (which embody more wisdom and perspectives than a few dozen economists in any central bank can, and – he hopes – with less risk of (eg) groupthink).

It was a bad call. But in isolation it can’t have mattered much. After all, the FOMC went on to cut over the next couple of months, reaching their (self-identified) floor in December 2008.

The second questionable call was the move to pay interest on excess reserves held at the Fed (“settlement cash” in New Zealand parlance). I’ve written about this move in an earlier post, reviewing a book by George Selgin. This step was taken to stop short-term interest rates falling further…..in the depths of the most serious recession in decades…..by underpinning the demand for (willingness to hold) settlement cash. Selgin argued that this move deepened and extended the US recession – an interpretation I challenged in the earlier post – but it certainly dramatically changed any relationship that had previously existed between money base measures and wider nominal variables (nominal GDP, inflation, or whatever) – one of Sumner’s points – and did nothing to assist in getting inflation and activity back on course. (Our Reserve Bank made a similar decision last March, moving to pay the OCR on all settlement cash balances and thus underpinning short-term rates, at a time when the Bank also thought it needed to do massive bond-purchasing programmes.)

And while Sumner constantly (and rightly) cautions about simplistic reasoning from price changes, one of his other points about this period – and how the Fed was too slow and unaggressive in its approach – is how surprising it was to see real interest rates trending up over much of 2008. Discount the extreme surge if you like – though Sumner will argue that changes in market prices like that (tied in with risk aversion, market illiquidity) probably in any case support monetary easing – but that real yields were higher in January 2009 than in January 2008 does not sit that comfortably with a story of an aggressively-easing Fed.

(At the time New Zealand had only a single indexed bond, then with about 7 years remaining to maturity. Yields on that bond did not start falling until November 2008, even though the economy had been in recession all year.)

But there is a tension in Sumner’s book. At least early on there is a sense that he thinks the Fed could have avoided the recession together if only they’d done a better job, but the specific failings he explicitly highlights cannot credibly have been large enough in effect to have avoided the recession (and further on in the book he notes that they might only have dampened the severity of the recession, which is a much weaker – and harder to test – claim).

In many ways his starting point is that the responsibility of a central bank is (or should be) to manage nominal spending in ways that avoid big and disruptive fluctuations (which often involve recessions, and sometimes exacerbate periods of banking stress). I have no particular problem with that. I still prefer something like inflation targeting (at least in countries like New Zealand and Australia) as the operational form that responsibility takes, while Sumner now prefers nominal GDP targeting (preferably in levels form, but in growth rates still better than nothing.

His bolder claim seems to be that if there is a recession – and he makes explicit exceptions for one where, as in March 2020, governments temporarily close down economies/societies – it is the fault of the central bank. And that is a step far too far for me. He might be right that in an ideal world no one would ever unconditionally forecast a recession, since they would also forecast that the central bank would take the steps required to forestall it. And so he might be right to say that neither the housing bust nor the associated financial crisis caused the US recession – central bank failure to react in time did – but that seems to me to simply assume away the problem, in a way that there are no easy or quick substantive or technical fixes for.

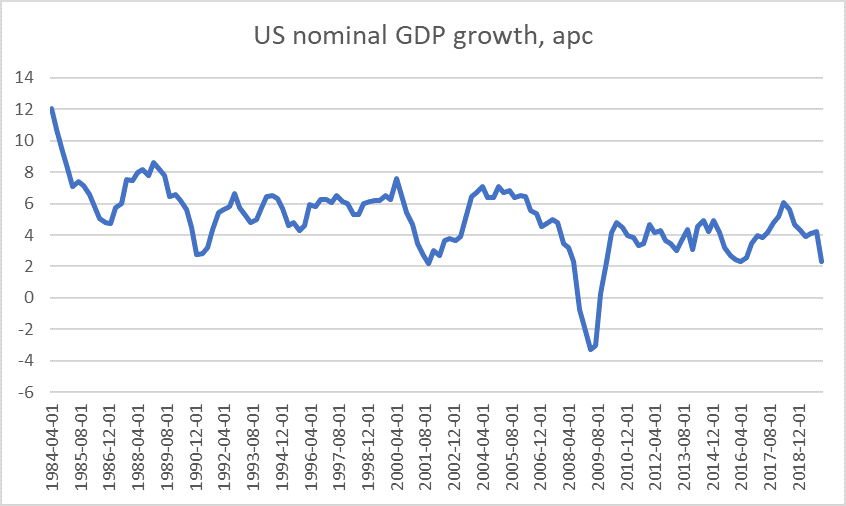

Here is a chart of US nominal GDP growth (note, as we see it now, not as people first saw it at the time).

Sumner thinks the Fed should aim to keep nominal GDP on a path consistent with about 5 per cent annual growth. Clearly that did not happen in 2008/09. Nominal GDP fell by more than 3 per cent in the worst 12-months and (consistent with then policy) there was never a later overshoot to get back on that 5 per cent annual growth levels track.

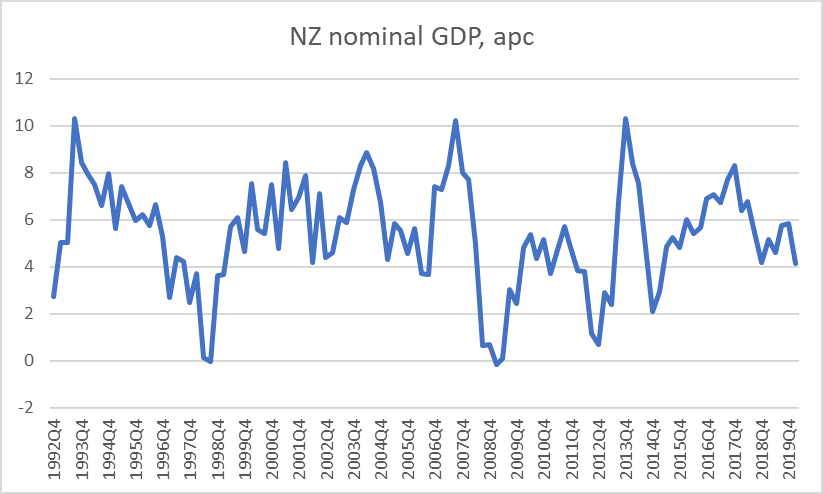

Here is a similar chart for New Zealand (from the low inflation era)

Our nominal GDP path is a lot noisier than that of the US – commodity price fluctuations are a key reason why NGDP targets are not a good idea for New Zealand (or Australia) – but you can see how much nominal GDP growth fell away in the two recessions (1997/98 and 2008/09) – and actually in the double-dip recession in 2010 too. Broadly speaking that doesn’t count as a successful outcome – but then nor does the real GDP recession, the rise in the unemployment rate, and (the extent of) the sharp fall in the core inflation rate.

But here’s the thing though. Had Alan Bollard – then the sole decisionmaker – been presented with credible forecasts at the start of 2008 that nominal GDP growth was going to go negative over the coming year, I have little doubt that he would have been prepared to cut the OCR sharply (he wasn’t exactly an anti-inflation hardliner). But he wasn’t. Not just from the internal forecasters, but from the wider forecasting community or the financial markets. Inflation breakevens weren’t plummeting, long-term real interest rates weren’t falling, the exchange rate wasn’t falling much (as late as May 2008 it was still higher than it had been at the end of 2006). The share market was falling back but (a) the New Zealand share-market wasn’t very representative of the wider economy, and (b) few if any one in New Zealand has ever put much weight on local share prices as an indicator. The Bank did not cut early or hard enough (and I was one of Bollard’s advisers until August 2008 and although I was one of those more focused on global risks I wasn’t recommending deep early cuts)….but we did not have the information on which to do so. I would argue that no one did. In a sense, it was the point of that period…..for a very long time no one understood quite how bad some of the lending had been, or who was exposed, or what the macro consequences (absent monetary offset) would be.

From all I read or saw of the US at the time, and since, I don’t think anyone in the US did either. It wasn’t as if the Fed was totally blind: they had been taken by surprise in 2007, but actually starting cutting in September (you can see in the chart above, nominal GDP growth was beginning to slow).

Could the Fed or the RB have done better? Almost certainly (some identifiable Fed mistakes above), but it is inconceivable that they could have prevented the recession – not because the techniques weren’t there, but because the information and understanding wasn’t.

One of my criticisms of Sumner’s book is that he largely avoids this issue, and more or less assumes much more was achievable over 2008/09 (the issues re the recovery are different but note that in NZ and in the US markets were often keener on tightenings than either central bank – and Sumner urges paying more attnetion to market prices). An example of what I have in mind is his treatment of Australia.

We are told that

Among all the developed countries, Australia was the one with that sort of devil-may-care attitude, and it breezed through the Great Recession with only minor problems. And yet from a conventional point of view the Aussies did the least aggressive monetary stimulus. Unlike most other developed countries, they did not cut interest rates to zero.

He goes on to present a table showing that average nominal GDP growth in Australia for 2006 to 2013 was much the same as in the previous decade (unlike the US and the euro-area).

And yet….the RBA was still raising interest rates into 2008 (I recall a conversation at a conference in early 2008 at which a very senior RBA figure expressed astonishment at what the Fed thought it was doing keeping on cutting), the RBA ended up cutting by 425 basis points, there was a huge fiscal stimulus, and yet here is the Australian nominal GDP growth chart.

And yet look how much nominal GDP growth fell away in that downturn (a bit more than in the US). And it wasn’t as if there were no real consequences, with the unemployment rate rising 2 percentage points.

I’m not saying it was a bad performance…..it might even have been about as good as the authorities could have managed. But that is sort of the point. Limitations of knowledge, understanding etc…..not just in central banks, but much more broadly.

I could go on, exploring some of this points and Sumner’s specific policy prescriptions in more depth. But this post has probably gone on long enough already. He favours targeting a futures contract on nominal GDP, which may be a reasonable idea (at least in the US context), but it isn’t going to change the basic problem around knowledge. In countries like New Zealand (as Sumner notes) something like an aggregate wages series would probably make more macroeconomic sense (but would have its own political problems). I’m all for using monetary policy aggressively, but there are limits to what short-term stabilisation can be hoped for, no matter the indicator, the specific target, the instruments, or the individuals.

(Rather than labour points about nominal GDP targeting, I’ll link to some remarks I made on the topic at a conference a few years back.)

Good books make you think, and think harder. The disagreements are often where the most value lies in forcing one to think harder about one’s own view. This one is worth reading and reflecting on. And I’m going to finish where the book does with a quote I endorse (even if a bit more relevant in the US than here):

In other words, the goal is a world in which policy makers don’t view fiscal stimulus or the bailout of bankrupt firms as a way of “saving jobs”, but rather as a sort of crony capitalism that favors one sector over another.

But there will still be recessions, real and nominal.

I don’t think anyone Reay could have anticipated the collapse that took place on LEH, as it was clear that Hank Poulsen either didn’t understand their importance, or, as some have argued, had a vendetta against Dick Fuld. Hence no one anticipated they’d let LEH collapse, which ricocheted through the system at lightning speed.

But by late 2007 there were many people calling for a deep recession in the US. I well recall countless global conference calls at the IB I was at, where the Head of Credit Research and the Head of Cross Asset research were beside themselves. Our US-based Head of Research, who’d worked ad an economist at the Fed, just couldn’t see it. They simply didn’t understand the house of cards that had been built up. But there was a great piece of research done by by Kansas City Fed, that went through the entire mortgage industry examining role of documentation, teaser rates etc. Reading that at the Coffee Bean on Orchard Road, at Christmas 2007 I remember the feeling of dred that came over me. We took a knife to our Asian GDP forecasts in January, halving our growth protection for China from 15% to 8.8% much to my China economist’s annoyance, but in retrospect we were still too cautious.

LikeLike

I recall many discussions with the RB international team in early 2008 who couldn’t see any reason why what was going on in the US shld matter to NZ at all (and I think thought I was rather obsessive to keep labouring the issue). And I make no great claims to any depth of prior understanding.

LikeLike

In 2007 – 08 I was working at UBS investment bank, in the sleepy backwater that was Group Treasury Funding and Liquidity. Things got pretty hot very fast.

UBS ran through its capital a couple of times, and was bailed out. I’ve never been abducted and gang probed by aliens, but if it happens, it may not be stranger or scarier than that period.

Bear went first. Many months later, AIG (the biggest insurer in the world), Lehman and Merrill Lynch (merged) were effectively all gone. From memory, most of this happened in less than a week. People were saying the remaining two American IB’s (Goldman and Morgan Stanley) would go bust by the end of the week…

Everything happened so fast.

At the time, the initial obsession was with moral hazard. This changed after Lehman / AIG.

Bernanke, Paulson et al saved the world, as far as I’m concerned.

The balance sheets of investment banks, back in the day, were extremely leveraged.

Another Great Depression was on the cards, without the bailouts. Paulson begged Pelosi on his knees, and the world kept turning…

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Utopia, you are standing in it!.

LikeLike

I think I’m more on Sumner’s side here: a lending confidence based recession can’t be blamed on banks because, as private organisations, they are fundamentally not responsible for money/credit stability. It is entirely on the central bank and the politicians that set the terms that the CB operates on and therefore to counteract all lending confidence / money supply based recessions.

In 2008 banks were no longer sure each other bank was solvent enough to lend to and this led to the recession, that wouldn’t happen in a full reserve banking system. I realise it is not quite this simple and shadow banking is still a potential problem, but under full reserve banking eliminating shadow banking whenever it arises would be much more likely to happen.

LikeLike

Full reserve banking might change the probability of bank failures, but I don’t think it would make a significant difference to the probability of future recessions (or even make them any easier to predict).

LikeLike

I’m not sure it would reduce (non-investment) bank failures as there doesn’t really seem to be any of those in the current system either. It’s about ensuring confidence in the stability of the system stays high at all times, that would greatly reduce the scope of lending confidence based recessions and thus limit the total amount and severity of recessions by eliminating this category.

Presumably supply (1973, oil) and demand (2020, covid) shock recessions would still happen. The Dot-com crash? That might have been moderated because of the limits on lending sprees that would exist as part of a full reserve system. The Asian Financial Crisis? I don’t know enough about it to say.

I think it’s pretty easy to know that you are in some sort of recession because the triggers are usually fairly obvious, but you do make a good point in that it can be hard to know exactly how deep or long the recession/downturn is going to be.

LikeLike

I think your final line sums it up:

“But there will still be recessions, real and nominal.”

I disagree with Sumner that recessions are the fault of central banks, or even that they should be completely offset by cb intervention. The 1987 share-market crash in NZ, or the subprime crash 2008 are both examples of irrational exuberance in the marketplace, rather than the fault of central banks, in my view. There is a misallocation of resources, that when corrected is going to result in a loss of output, irrespective of any central bank remedial actions.

In addition, I don’t think the extent of the 2008 crash was realistically easily identifiable before the event. I don’t believe that even insiders who had spent decades looking at the balance sheets of the banks had any idea how leveraged the market was. Market watchers assumed real and effective hedging was in place, or that exposures weren’t as high as they later turned out to be.

For example, AIG owned a relatively tiny portfolio of Credit Default Swaps amongst their trillion-dollar house and car insurance products. Only a tiny fraction of their employees worked in the financial services department issuing CDS, and even these people probably didn’t properly appreciate how leveraged as a whole the banking industry was. No one saw the whole picture.

There is no way that central bank action could have anticipated and then stopped nominal GDP from falling in 2008.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this very useful and interesting overview Michael.

Scott Sumner’s recent review of monetary policy thinking around the lower bound is also pertinent. See here if interested https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/sumner_princeton-school-and-zero-bound_working-paper-v1.pdf

Personally, I find the notion very disquieting that central banks can and should aim to use monetary easing to make a credible “promise to be irresponsible”. Economists have good reason to worry that once double-digit inflation expectations are entrenched it is very costly in output losses and unemployment to get them down.

To propose that central banks seek to promise to be irresponsible looks too much to me like proposing to let a child play with fire.

My concerns are time inconsistency, moral hazard and the porblem of long and variable lags. To that long-standing list I would now add the political pressures on central banks to fund fiscal deficits at ruinous interest rates for lenders. There is evidence that central bankers are becoming more political as the lines between monetary and fiscal policy are getting more blurred.

I am still keen to see really good empirical evidence that monetary policy can be consistently used (eg in NZ) to fine-tune the real economy in the short run without jeopardising medium term price stability. (This is the old rules vs discretion debate.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Bryce. Sumner argues that the monetary policy lags are much shorter than we typically regard them as being. He seems quite confident of it, but the only evidence he adduces is early in the book where he has a nice chart – I think from his depression book – showing a surprisingly tight correlation (at relatively high frequency – prob monthly) between asset prices changes and industrial production.

I guess you won’t dispute that central banks can influence nominal GDP quite substantially, so the real question is whether they can usefully do something to stabilise real GDP,

Thanks for the reminder that I need to read the new paper too. In the book I was a bit surprised at how little he engaged (basically not at all) with issues around eliminating the lower bound (whether or not one agrees with doing so).

LikeLike