Typing the date I notice that in the Christian calendar today is the Feast of the Annunciation – the announcement of a coming Saviour and Redeemer – and that today it is nine months until Christmas. One can only wonder how things will be, here and abroad, on Christmas Day 2020.

But what about current policy and related issues? First, to get out of the way a couple of important, but less central or immediate issues.

The first is around accountability. Personally, I’m uneasy that Parliament is simply closing down for the time being, in the middle of one of the most severe crises in our history, with an unprecedented usurpation of power by the executive. But whatever the shorter-term questions, challenges etc (that the planned Select Committee is unlikely to do much about) there will be a need for a serious reckoning with how the authorities, political and official, handle all stages of this pandemic – those past and those, perhaps over many many months – still to come. After the 1918 pandemic, the New Zealand government set up a Royal Commission, which reported back within about six months. The report is here. It seems like a good model for a variety of purposes: accountability, documenting issues and experiences, and learning from what worked well (and what do not) for future pandemics. It would be a welcome commitment to openness and accountability if the Prime Minister would now commit that once the pandemic is passed such an independent and powerful Royal Commission will be established (in case there is a change of government before then, ideally that would be endorsed – or done jointly with – the Leader of the Opposition.

In the meantime, a serious commitment to accountability and openness – around contentious and highly uncertain re effect policies (and even choices not to act) – would be enhanced if the current government would commit to the pro-active release of all Covid-related papers going to Cabinet, to Ministers, and to government agencies and officials who have either independent policymaking power or delegated authority to set operational policy on these matters, (There might perhaps be a few – very few exceptions – around national security, but openness builds trust – or exposes weaknesses, which in turn is a basis for correcting and improving things.)

The second is around economic data. New Zealand’s official data are pretty mediocre at the best of times – one of only two OECD countries with only a quarterly CPI, badly lagging GDP numbers, no monthly read on the unemployment rate, and so on. It is hard not to imagine that the official data will only get much worse this year, with long delays even if adequate numbers are finally able to be patched together. It would be helpful for analysts if Statistics were to give an early outline of their plans and contingency plans.

But in the meantime, it would also be highly desirable if the authorities (whether SNZ or economic agencies like MBIE, the Reserve Bank or the Treasury) and getting together a timely public dashboard of high-frequency administrative data. Things it might cover could include, for example:

- daily or weekly new welfare benefit applications,

- weekly bank credit data

- weekly data on electronic payments

- daily or weekly arrivals data

These – and no doubt others – would be valuable not just now as we tumble into the abyss, but through all the inevitable ups and downs – perhaps quite volatile ones – in the coming months. If/when we eventually get official data it will be good for the economic historians (and the Royal Commission) but for now we need a range of timely high frequency data (no doubt all stuff that could be compiled by people working from home).

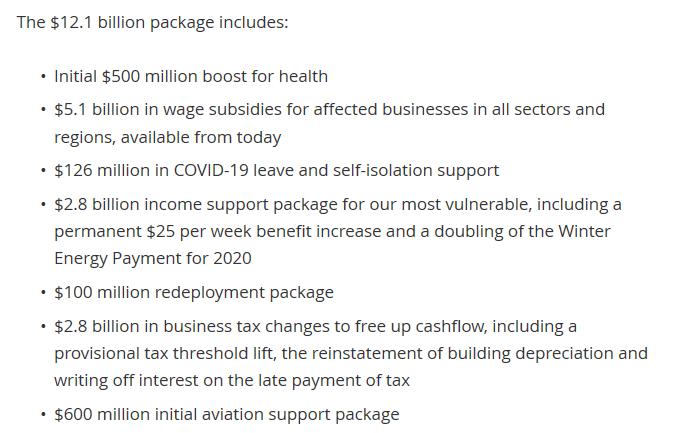

What I really wanted to focus on today is the announcement by the government and the banks (and the Reserve Bank) yesterday afternoon. There were very few details in the announcement, but what we know is this:

The package will include a six month principal and interest payment holiday for mortgage holders and SME customers whose incomes have been affected by the economic disruption from COVID-19.

The Government and the banks will implement a $6.25 billion Business Finance Guarantee Scheme for small and medium-sized businesses

The scheme will include a limit of $500,000 per loan and will apply to firms with a turnover of between $250,000 and $80 million per annum. The loans will be for a maximum of three years and expected to be provided by the banks at competitive, transparent rates. The Government will carry 80% of the credit risk, with the other 20% to be carried by the banks.

The Reserve Bank has agreed to help banks put this in place with appropriate capital rules. In addition, it has decided to reduce banks ‘core funding ratios’ from 75 percent to 50 percent, further helping banks to make credit available.

Take the “payment holiday” first. I guess it was always likely for customers that were only fairly modestly indebted and had a fair amount of collateral to offer – indeed, in those circumstances the willingness to offer such an extension is obviously sensible and mutually beneficial.

But do note that this offer by the banks – how much was it a genuine offer, and how much were they coerced into it – includes (or seems to) all existing residential mortgage and SME borrowers. Just on the mortgage side, that includes those who will have taken on loans in the last year or two with LVRs well in excess of 80 per cent. It seems highly likely that market-clearing house prices will be falling at present, perhaps really rather a lot, even if the market is highly illiquid and there won’t be any open homes for the time being. And although people don’t have to stump up with the cash for the next few months, interest is still accruing. Floating first mortgage rates are still around 4.5 per cent, and on a $500000 mortgage a household will run up perhaps another $12000 of debt in the coming six months. An 80 per cent LVR last month could easily be a 100 per cent LVR next month, and worse than that if the security had to be realised in the near future. Typical business lending interest rates are higher than those for residential mortgages.

I am not, of course, suggesting that banks should waive the interest. But these continued high interest rates just reinforce the absurdity of the Reserve Bank Monetary Policy Committee simply refusing to cut the OCR any further, having cut it by only 75 basis points in the biggest economic slump of our lifetimes. Setting monetary policy in a way that delivered, say, zero per cent low-risk retail lending rates would deliver real sustained relief to borrowers, and treat depositors as is appropriate at present (time having no value, or even negative value).

And what of the business loan guarantee scheme? It looks relatively attractive to the banks, especially as (at present) there is no sign of any guarantee fee, however modest, and will enhance/underpin to some extent and for some classes of customers their willingness to lend a bit more. Since banks know their own customers they still need to make decisions about which firms are likely to survive, with enough prospect or security that the bank is likely to get its money back.

But I doubt it will be that attractive to many businesses at all, and they may be something of an adverse selection problem in those who actually seek to use it. And those interest rates – the official statement says “competitive transparent rates”, while RNZ this morning referred to them as “normal commercial rates”. Time has little or no economic value at present, at least across the economy as a whole. Risk-free rates should be negative in a deflationary slump like this, and normal commercial rates – which always carry a risk margin – probably should be pretty much zero. That is hundreds of basis points less than firms are, and will, actually pay. Fixing that would provide real relief, and perhaps a bit more willingness to take on a bit more debt, but the Minister and the Governor simply refuse to do anything about it.

But if debt service relief – real relief, not just delays – would be of considerable help, the real issue remains the dramatic slump in revenue many firms have already seen and that many more are just now beginning to experience. And there is extreme uncertainty about (a) how much worse things might get (bounded at zero revenue I guess, but often with fixed outgoings), and (b) when, and how strongly even then, things might improve. No one knows, and certainly your typical owner of a modest-sized business doesn’t. Many of them won’t have much collateral, and they will have low profit margins at the best of times (Martien Lubberink at Victoria yesterday highlighted that The Warehouse group seems to fit that bill), and for many it won’t be obvoius why it is worthwhile to borrow, rather than to simply close down now and perhaps get lucky enough to be among the earlier people to realise any remaining assets. Even if there is a robust business there five years hence, it won’t be so for the current owners if they take on lots of new debt in the interim.

It may get a bit tiresome to keep reading it, but the government’s approach still does not seem to recognise – or if it recognises the point, be willing to do anything serious about it – that the biggest issues around the survival of firms is dramatic income loss and extreme income certainty. While they avoid confronting that more and more businesses will close by the day.

Which, of course, brings me back to my income guarantee proposal, guaranteeing households and firms (to the extent they maintain paid employees) 80 per cent of last year’s net income for the coming year. It is the sort of national economic pandemic insurance policy we might well have signed up to if we’d thought seriously enough about the issue 20 years ago (experts have always advised that a really severe pandemic would be along one day). We can’t – or shouldn’t – go offering that level of comfort indefinitely, but given the position successive governments have kept net public debt to (zero per cent on the best OECD measure), we can – and should – certainly do it for a year. It buys both firms and households (borrowers) and banks a reasonable amount of time. If, perchance, economic life looks like returning to normal in six to nine months, it would have served its purpose, and avoiding many liquidations and insolvencies. If there is still huge uncertainty, or worse, by then, everyone can start adjusting further. It isn’t a policy that will or should save every firm, or perhaps even every household, but it would offer a valuable affordable buffer – one that we’ve either paid the premium for in the last 25 years (getting/keeping that low debt) or could do so over the 25 years after the crisis in over.

And we should back it up with a 20 per cent (legislated) temporary cut in wages (and probably rents). There are plenty of households that are going to do just fine economically this year, even as the economy’s capacity to generate returns has slumped dramatically. It is about fairness, shared sacrifice, (and perceptions thereof) and about actually easing the burden on some of those firms (whose “profits” are now deeply negative) everyone wants to hold together if we can. Complement it with a windfall profits tax if you like for the few firms that might do exceptionally well through all this.

I really hope it doesn’t take much longer before the government is finally willing to confront that “income loss and extreme uncertainty” nexus, and be prepared to take steps that meaningfully address it, in ways that help stabilise for now (and to the extent possible) firms, households, and (thus) underpinning the ability of banks to lend.

Oh, and what stops them just getting on and doing the little it would take to dramatically cut interest rates?