Wednesday mornings at present don’t find me at my most relaxed and sanguine. It is the morning I join the supermarket queue at 6:50am (a bit shorter this week than last), and notice that the owners have now erected shelters for customers to queue in the rain – winter coming and all that. And I’m reminded of the Prime Minister’s fantasies, when she was urging people not to stock up before the lockdown, that the supermarkets would run normally no matter how intense any lockdown. When milk is scarce (in New Zealand….?), flour is available patchily at best, there is little or no fresh fish (my supermarket is about a kilometre from where the fishing boats moor), and the availability of almost anything else seems to be something of a lottery, it is a strange definition of normality. Add to that packing groceries into bags in the carpark – where it is cold, but not yet wet. As it is, it is a bit like a bank run…if people come to doubt, rationally or otherwise, that the bank can meet its debts, it is an incentive to get out entirely while you still can. Here, the medium-term risk probably isn’t the New Zealand produced basics, which will eventually get sorted out, but the foreign-produced non-perishables (not much affected by New Zealand government choices). Which year will supplies of those get back to normal?

Anyway, having got that off my chest, it is time to turn back to monetary policy and the Reserve Bank of New Zealand. The Governor is scheduled to appeared before Parliament’s Epidemic Response Committee tomorrow. If the Committee is serious about holding the government and powerful independent government agencies and figures to account, there should be a whole series of hard questions posed to the Governor (and to his colleagues on the Monetary Policy Committee, the external half of whom never seem to face any scrutiny, challenge, or questioning. There are important questions about the past, the present, and (a few) about planning for the future, and only a few can be addressed in a short session (many are likely to need to wait for a Royal Commission or a later external review of the Bank’s handling of the crisis).

At an overarching level, there should be much the same question for the Bank as for the rest of government: why is there so little transparency, so little pro-active release of relevant background and decision documents. Anyone would think we didn’t have a central bank that likes to boast about how transparent it is, or a government that used to boast that it would be the most open and transparent ever. Say it often enough and it still doesn’t change the (quite different) reality.

The first set of questions might reasonably be about the past and Reserve Bank preparedness.

For example, Committee members might consider asking the Governor about the state of preparedness of unconventional monetary policy when he took office (in March 2018), many years after other countries had already been undertaking such activities and, in some cases, dealing with negative official interest rates.

And as it is now almost two years since the Bank published an article on options around unconventional policy, including negative official interest rates. In that article, the authors observed

Overall, it appears that the Reserve Bank could implement negative interest rates, with the potential leakage into cash relatively small in value terms at modestly negative rates.

So the Bank might reasonably be asked what steps the Bank had put in place by this point to ensure that there were no technical obstacles to using a modestly negative OCR (eg checking out whether bank systems were readily able to cope and, if they were not, prioritising getting them ready)?

Since the Bank was well aware of the limits to how deeply the OCR could be cut – because of the possibility of conversion to zero interest cash – what work programmes did the Bank have in place to explore options for easing, or even removing, the constraints (all of which were under the Bank’s direct control). If there are such papers, the Committee might ask for them to be released.

It might be reasonable for the Committee to ask what modelling and scenario-based work the Bank had undertaken in recent years to prepare for the possibility of a new serious economic downturn while the initial starting level of the OCR was still very low? How, for example, did they factor in the observation that in typical recessions the OCR (or equivalent) has been cut by 500+ basis points, in turning often helping generate a large reduction in the exchange rate. Macrostabilisation in the face of deep adverse shocks being, after all, at the heart of why we have a central bank with discretionary monetary policy.

In a lengthy interview last August, the Governor indicated his preference for using a negative OCR before using large scale asset purchases etc. As late as his speech on 10 March 2020, a negative OCR was still being presented as a live option. What changed? When?

At the February Monetary Policy Statement the Bank was quite upbeat about economic prospects here and abroad, even moving to a mild tightening bias. Almost two weeks later, in a tweet approved by the Chief Economist, the Bank was still talking up economic prospects for 2020. Doesn’t this suggest an extraordinary degree of blindness, backward-lookingness, and complacency about the risks just about to break over us? To what extent, if at all, had the Ministry of Health or The Treasury been alerting you by this time to the scale of the health and economic risks?

In your speech on 10 March and in interviews immediately after that, the Bank was still coming across as extraordinarily complacent and reluctant to do anything with monetary policy. Given the way the Bank had responded to past exogenous shocks threats, how do you justify the refusal to act for so long, perhaps the more so when you knew the limits of conventional monetary policy were approaching and (in various statements/interviews last year you were alert to the threat of inflation expectations falling away in any renewed downturn). The Governor might also be asked if the technical working papers promised in his speech are now ever going to be released.

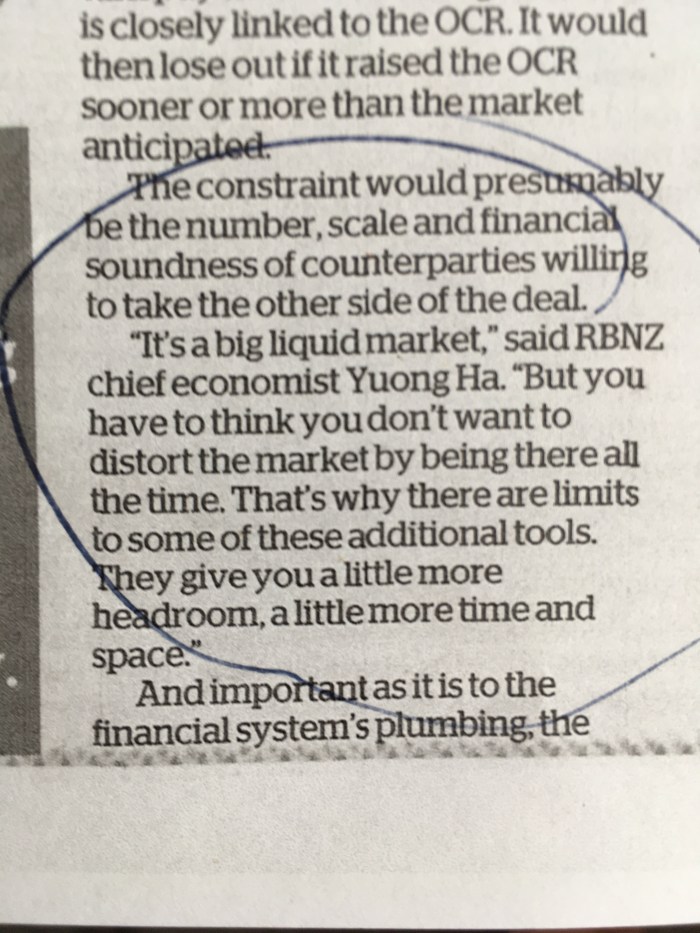

And finally, in the pre-action, phase, it might be reasoanable to ask whether the Bank’s Chief Economist was correctly quoted in the Herald on 13 March, when he is reported as saying – of the various possible unconventional instruments (asset purchases and the like) – that “there are limits to some of these additional tools. They give you a little more headroom, a little more time and space.”

The Present

The Monetary Policy Committee finally acted on Monday morning 16 March. The OCR was cut by 75 basis points to 0.25 per cent, but a floor was put in place at that level. The Committee pledged not to change the OCR “for the next twelve months”. It was an extraordinary commitment to make amid so much uncertainty, and again suggested a degree of misguided complacency or comfort that something close to the worst had already been seen.

But, most importantly, the new floor came completely out of the blue. There had been no hint of it in the speech or interviews the previous week and we have still seen not a shred of analysis in support of a floor at that level. Various central bankers were wheeled out to tell us that not all banks’ systems could cope with negative rates and that the Reserve Bank didn’t now want to put any pressure on those banks.

So, a reasonable question might be when did the Governor and the MPC first learn that not all banks’ systems could cope with negative interest rates? (For that matter, when did they ask?) How many banks had this system failure, and roughly what share of the banking market do they account for? Are the issues with retail or wholesale systems bearing in mind that many overseas wholesale rates have been negative for several years)? If retail, given that term deposit rates are still mostly above 2 per cent, and lending rates higher (often much higher) than that, why couldn’t the OCR have been cut further?

Another reasonable question might be to ask what steps is the Bank now taking – and at what level of the organisation – to insist that banks either get ready for negative rates or risk being left to one side in favour of those that are ready? (Bank spokespeople have suggested a negative OCR might be an option some time down the track.) What deadlines have been given by the Bank? What commitments made by the tardy banks? Why is there no naming and shaming (in fairness, it might be easier for a journalist to ask each bank and do the “naming and shaming” that way).

The Governor has indicated that urgent work is proceeeding on details of a deposit insurance scheme. What, if any, urgent work is underway on easing or removing the constraints that give rise to the effective lower bound on nominal interest rates? If none, why not?

The Bank has announced a large scale purchase programme of government (and now local authority) bonds. How would the Governor evaluate the effectiveness of that programme. It is easy to see that it has limited the sell-off in government bond yields, and perhaps in some other asset markets, and thus limited any tightening in monetary conditions. But relative to the conditions the MPC delivered on 16 March, is there any credible evidence that the asset purchase programme has eased conditions, and thus materially substituted for a lower OCR itself? If so, what are the relevant transmissions mechanisms.

The Bank has injected huge amounts of settlement cash to the banking system. Given that all settlement cash balances are now being remunerated at the OCR itself – the previous tiering system has been scrapped for now – aren’t you at risk of further holding up market interest rates by offering almost unlimited risk-free investment at 0.25 per cent? (This is a concern that, for example, George Selgin had posed in the US in the wake of the Fed’s earlier large scale asset purchases.)

The Governor might reasonably be asked about the falls in inflation expectations observed in both surveys and market prices, and invited to offer his thoughts on how those expectations are likely to be returned to around 2 per cent when (a) his asset purchase programme is achieving little overall loosening, and (b) MPC has pledged not to cut nominal interest rates further, no matter how bad the economic and inflation situation gets.

Relatedly, the Governor might be invited by the Committee to tell it how much real retail interest rates (borrowing and lending) have fallen since the start of the year, and to contrast that with the scale of the reductions in each previous New Zealand recession. Hint: there has been almost no reduction at all (and, at a wholesale level, the real five year government bond rate is at the same level now it was in early December).

Since the Reserve Bank’s last economic projections were completed in early February, perhaps the Governor might be invited to comment on the inflation numbers in The Treasury’s economic scenarios published yesterday (the Secretary to the Treasury is, after all, a non-voting observer at the MPC table). The best of those scenarios had inflation at 1.25 per cent for each of the next two years (several scenarios had negative inflation), outcomes which – if realised – would risk further entrenching lower medium to long term inflation expectations. Are such outcomes consistent with the Bank’s own thinking, and if so would they be acceptable to the Committee? If not, why won’t they ease monetary policy further? And if the Governor thinks the Treasury numbers are too pessimistic, what channels does he expect to be at work to avoid such low inflation?

Perhaps time might be spared for a hypothetical: what does the Governor think would be worse, in terms of the economic responsibilities the Bank has, if the OCR were able to be set at,say, -5 per cent and retail lending and deposit rates were commensurately lower (modestly negative)? Inflation? Employment? What? How?

Given the Governor’s enthusiasm for the employment dimension of his new mandate, how does an adamant refusal by the MPC to cut the OCR further no matter how bad the economic situation gets square with all that rhetoric?

Does the Governor (and MPC) now regret the “no change for 12 months” commitment? What positive stabilisation value did it add, given that no serious observer has ever supposed that OCR increases were at all likely in the year after 16 March?

Here it is perhaps worth adding that the Governor is well known as an enthusiast for the active use of fiscal policy, to pursue all sorts of personal agendas. However, he is Governor of the Reserve Bank, responsible for monetary policy, and his refusal to actually use the tools he has – and is statutorily charged with using – seeems little short of dereliction of duty.

The Governor might also be asked about the foreign exchange intervention option. Very unusually for a New Zealand recession, the exchange rate has fallen very little at all (even though one of our major export sectors is just shutdown completely for the time being). The Bank has indicated that foreign exchange intervention is one of the tools open to it to attempt to ease monetary conditions further. Why has this tool not yet been deployed? How effective does the Governor expect that it could be? (For what it is worth, I’m sceptical as to how much difference it will make, but (a) we won’t know until we try, and (b) if it is tried and failed, it would help turn the spotlight back on the adamant refusal to adjust the OCR.)

And finally for this section, there was that op-ed of the Governor’s a couple of weeks back that concluded with this injunction

Support each other, think beyond just the next six months or more, and visualise the role you can and will play in the vibrant, refreshed, sustainable, inclusive New Zealand economy.

Just which planet was he on as he touted this vision of a “vibrant, refreshed” New Zealand economy as the wreckage mounts of one of the biggest economic shakeouts, and losses of wealth, ever?

Oh, and when he was stating at about the same time that New Zealand had perhaps the strongest banking system in the world, how does he square that with his relentless rhetoric last year in favour of much higher ratios of bank capital, all the time suggesting that even if that were done our banking system would not then be out of step with international norms?

The Future

Why will the Reserve Bank not publish all relevant background and analytical papers relevant to monetary policy decisionmaking this year?

The Reserve Bank’s balance sheet has been hugely increased by the interventions undertaken in this crisis. Experience in other countries, after the last recession, suggests that getting back to normal size is likely to be a long slow process. One of the risks of very large central bank balance sheets is that central bankers then become part of the credit allocation process itself, favouring some sectors, disfavouring others (in ways usually more appropriate to fiscal policy). What protections do citizens and taxpayers have against balance sheet choices being made by the Governor – still the single decisionmaker in key areas – in ways that advance his personal political agendas.

What approach are you planning to take to economic forecasting for the May Monetary Policy Statement? Can any central forecasts be particular meaningful or instructive in such a climate of extreme uncertainty?