Over the last three rather tumultuous US trade policy weeks, I’ve read these four books. I started with Irwin (whose book had sat on my pile for years, consulted from time to time but not read) in a week of lots of flights and hanging around airports/hotels, and then one thing led to another. In a somewhat related vein, I’m expecting to finish today John Taylor’s book on his time (2001 to 05) as US Treasury Under Secretary for International Affairs for a, perhaps rather complacent, echo of a somewhat less troubled age.

All four books made for interesting reading, although in truth the fourth (Dobson) is perhaps likely to be of niche interest only, although it was a reminder of an age (mostly, the Cold War) when alliances were thought to matter greatly.

Doug Irwin’s history of US trade policy dating all the way back to the colonial era has been often lauded in the years since it was published, and deservedly so. It is a fascinating and apparently pretty comprehensive history, all the more so if your knowledge of 19th century US history and politics before the Civil War is as patchy as mine. There was, for example, what Irwin describes as “the most dramatic self-imposed shock to US trade in its history” [a description that probably still holds even this month], legislation in 1807 that “prohibited all American ships from sailing to foreign ports and all foreign ships from taking on cargo in the United States. Although foreign ships were permitted to bring goods to the United States, few did so, because they would have had to return empty. The embargo brought America’s foreign commerce to a grinding halt…” The embargo didn’t last long but while it did it was enormously disruptive and costly (imports at the time were around 7 per cent of GDP).

The book was also a helpful reminder that high tariffs in the US started out primarily as a revenue tool (small Federal government, and a limited number of ports so – as in various countries more recently – tariffs were generally easier to collect. Income tax was also unconstitutional in the US in the 19th century. New Zealand’s early tariffs were also primarily about revenue.)

But two of the points I wanted to comment on appeared on pages 2 and 3 of the book. From page 2, “Congress is at the center of the story because it is the principal venue in which trade policy is determined. Producer interests, labour unions, advocacy groups, public intellectuals, and even presidents can demand, protest, denounce, and complain all they want, but to change existing policy requires a majority in Congress and the approval of the executive. If the votes are not lined up, the existing policy will not change.”

The book was published as recently as 2017.

This month, we can only yearn for Congress to reassert its constitutional authority and to once again take the central place in the story. One of the fascinating dimensions of the book is how little involvement presidents really had in trade and tariff policy perhaps until the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934. Even then the scope of power delegated to the Administration was quite limited and time-bound, with authority having to be renewed every few years. The US tariff schedule was primarily a matter for the Congress.

Perhaps some of Trump’s recent moves will eventually be held not to have been authorised by the various pieces of legislation under which Congress has delegated far too much of its power to the President, but if the insane policies are Trump’s own doing, they have been enabled by supine legislators over many decades.

And then, on page 3 of the book, Irwin makes his case for his book (the first major history of US trade policy since 1931) thus:

“Since then the United States has moved from isolationism and protectionism in its trade policy to global leadership in promoting freer trade around the world”

As a claim, it was probably always a bit of a stretch – and Irwin doesn’t shy away from describing the quotas (under pressure and threat from the US) on exports of Japanese cars in the 1980s, or things like the Multi Fibre Agreement, only completely unwound 20 years ago, even if he is perhaps light on agricultural trade restrictions and subisidies (eg) – but that was 2016/17, and this is now. Those were the days.

Irwin concludes his book by noting that, amid all the ups and downs and political dramas around this or that aspect of trade policy, there had been three broad eras in US trade policy history (to 1860, from 1860 to 1934, and since 1934) and (in words that must have been written very early in 2017 at the latest) “if it took the Civil War and the Great Depression to bring about a major shift in US trade policy in the past, it is hard to anticipate the next political or economic jolt that might put it onto a different track, the election of President Trump notwithstanding.”. Too which I guess we can only wryly reflect that – in the old line – forecasting is hard, especially about the future.

Fishman’s book, Chokepoints, was almost equally fascinating, but much more contemporary being published just this year and focused on US economic warfare over the last couple of decades – with a focus on relations with Iran, Russia, and China – from the perspective of a well-connected academic who was an insider (State, Treasury, Defense) for a time. It really is well worth reading – with positive blurbs from all sorts of prominent people – but if you only want a review, this from Foreign Affairs is a good taster.

There has been rising global unease (among traditional US friends and allies) over the weaponisation of the financial system by the US in the last couple of decades (and other recent books worth reading in this area are Daniel McDowell’s Bucking the Buck and (former French official) Agathe Demarais’s Backfire: How Sanctions Reshare the World Against US Interests). Former Bank of England Deputy Governor Paul Tucker in his fairly recent book on the international order was clearly uneasy about the extent and reach of US sanctions policy.

There are two main chokepoints. One – around chip technology – isn’t really new. Dobson’s book (see above) is a reminder that economic warfare during the Cold War was in large part about controlling the exports of technology to the Soviet Union and its satellites. Overall trade as a share of GDP was never as high between the eastern and westerns as that between the West and China today, but nonetheless the Soviets were keen to get access to advanced Western technology and for decades there were fights (inter-agency in the US, and with allies) around just what should be banned and what permitted, and what approach might best balance commercial and geopolitical interests. Extraterritorial US sanctions were even briefly in place in the 1980s.

But use of the financial system, and the dominant position of the US dollar, as a direct instruments of leverage/sanctions, is newer. Fishman is a champion of the US approach, which often relies not on sanctions directly on other countries, but on the ability of the United States to penalise, and exclude from the dollar systems and markets, private companies – American or foreign – who might have anything to do with countries, entities, or people targeted by the US. Or to, in effect, compel, SWIFT – based in Belgium – to accede to US information demands. US sanctions on Iran were enforced this way, to the immense frustration of many European governments who were unable stop European companies/banks responding to (pretty draconian) “incentives” on them from the US. At a more individual level, apparently when Hong Kong’s Carrie Lam was sanctioned by the US, even Chinese banks had little effective choice but to stop dealing with her, forcing her to fall back on cash for personal transactions.

You or I might or might not agree with the US foreign policy approach in each of these cases. Many, for example, are probably sympathetic re pressure on Russia (although as book notes, in reality pressure on Russia would have been a lot greater if the West – US perhaps most notably – had been willing to endure the much higher prices that an effective embargo would have involved), but what should probably sober us all is the power it delivers to a rogue president to do exactly as he pleases, using this economic warfare weapon (a variant on the general point that in providing powers to governments one should always think first about how the other side might use it when their time comes).

Take, for example, this extract from the Conclusion to Fishman’s book (written before the return of Trump):

“The United States should also explore novel uses for sanctions and export controls. Some of humanity’s biggest challenges today, including climate change and the risk of unconstrained artificial intelligence, are transnational collective-action problems – not usually the province of economic warfare. But just as Washington can bar companies from dealing with Iran or Russia, it could bar them from participating in carbon-intensive energy projects anywhere in the world.”

Just breathtaking. And if you are, perchance, a Green Party supporter and think this possibility a “good thing”, turn it round and imagine it applied to some other cause where you and some US President might have opposing views. Think of that sort of power used more broadly historically: support our war of choice on Iraq or…..you’ll be cut from the US financial system. And if one might have been inclined to scoff at the prospect of such extremes just a few months ago, we now have the rogue lawless US President in office, apparently unbothered by any ideas of alliances, mutual trust, and anything beyond the flattery of the tributary. For good and ill these are real powers, able to be used (and actually being used) today. I can think of causes where such power might be used for good, but any such fearsome power exercised by one state – and more so one person – at next to no near-term cost to those wielding it is pretty fearsome to say the least. In a decent, responsible, and judicious person, let alone Trump.

People might reasonably push back and note that in WW1 and WW2 neutral rights (to trade) took a battering at the hands of the belligerents (often our side, since the British, and then the British and Americans, jointly had effective control of the high seas). And if, as Thucydides, “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must”, at least those WW1/WW2 interferences were a) at a time of legally declared international war, and b) for the most part didn’t attempt to reach behind national borders. Not like, as above, the suggestion that the US alone should be able to determine what sort of energy projects a country undertakes. (To be clear, I’m not aware of any politician having proposed this: I’m responding to the proposal in the book.) It is a power too far (as even some more reflective US figures have appreciated – for example the cautions offered by the then US Treasury Secretary in 2016)

At this point, exacerbated by the events of recent weeks, there must be many (and many more) people wishing for the dethroning of the dominant position of the US dollar. And that might be so even if you regard the increasingly lawless and untrustworthy rogue United States as, taken together, immeasurably less evil than the CCP-controlled People’s Republic of China.

All that said, it is hard to see it happening any time soon, how it could be brought about, or even what such a change would practically amount to.

People talk loosely of the USD as “the reserve currency”, but in doing so they tend to be conflating quite a range of things. At the narrowest level, there is the currency that most central banks hold most (although far from all) of their foreign reserves in (here New Zealand is a – very sensible – exception in that, enabled by being very small, our foreign reserves are widely spread across a range of currencies). But countries with properly floating exchange rates actually don’t need much in the way of foreign reserves and often don’t hold that much. Moreover, even among the countries that have run up very large reserves, holding their real exchange rates down to some extent, the biggest increase occurred back in the 00s. And it isn’t that obvious from the data that the US ever got any particular benefit from having countries holding the bulk of their reserves in US dollars, most especially in the floating era now 50+ years old. If countries were to shift away from USD reserves holdings it is not obvious the US would be particularly worse off either (as someone who used to champion the RBNZ approach in house, I really do recommend it for small and middling countries).

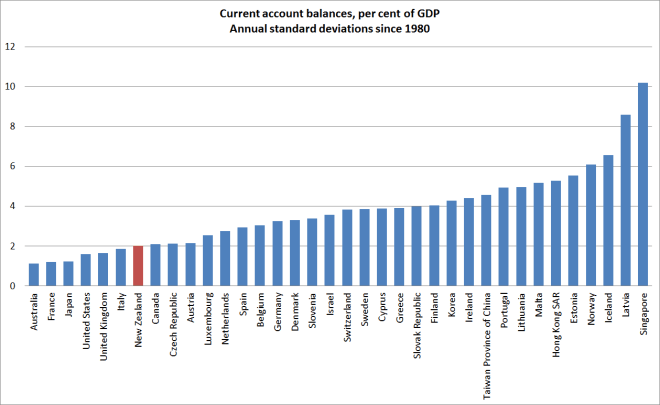

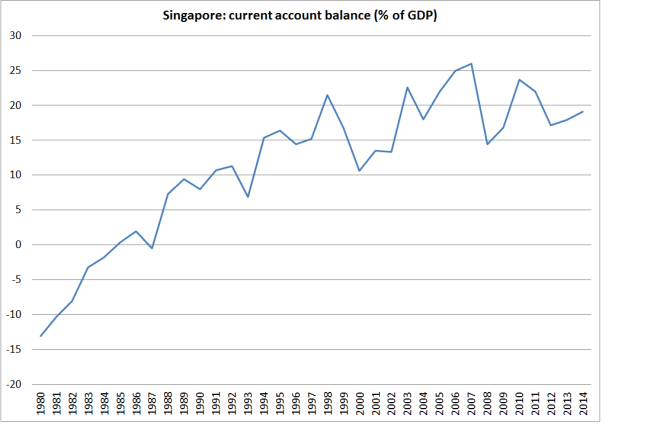

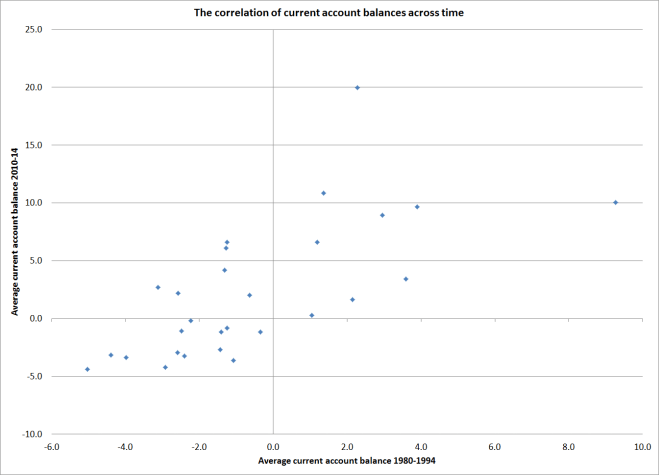

There is a lot of loose talk about how being “the reserve currency” enables the US to run imbalances other countries couldn’t. Some US MMT champions even focus on the US as somehow uniquely able to adopt their approach. But it really isn’t so. Look, for example, at the fiscal imbalances in Japan, or the current account deficits (and large negative net IIP positions) that places like New Zealand and Australia (and others) used to run back in the 00s. You do not need to be a “reserve currency” to be able to borrow in your own currency at pretty affordable rates. And, like it or not, the US – unlike Antipodean economies – is always going to be large economy (with a significant weighting in global asset allocations).

I can’t help thinking that what matters much more is the (largely unconscious) market choice to use USD as the reference currency (eg in most foreign exchange trading), and the size and depth of US markets, including debt and equity funding markets, that really matters (including in giving the US that economic warfare power discussed above). And those things aren’t about central bank choices at all. Markets could, eg, trade NZD or AUD mainly against the yen or the euro, but they don’t. And the network efficiencies from those evolved market practices are strong, and very unlikely to be easily displaced. In principle, perhaps, the euro could be a viable replacement – or something like co-equal role – but there isn’t the market depth, and it is only a decade or so since break-up (or at least break-out risk re Greece) was very real. As for China, there is no capital account openness and whatever one thinks of the lamentable trend in the rule of law in the US, or the rather random risk of being stopped at the airport or picked up off the street, no one in the rest of the advanced world is going to take Chinese ideas of rule of law (what suits the Party) in preference.

There is lots of discussion around these topics on the way in which the US came to displace the UK 100 or so years ago. I’m not sure that a lot of it is overly helpful, since on the one hand we’d been coming then off a metallic base for currencies (including through the heyday of London pre WW1), and there was an (increasingly evidently) larger economy and market to take much of London’s dominant role (and of course two World Wars didn’t help). This is a fairly unique situation, and it isn’t easy to see how things evolve away (at least without much more direct other-government interventions than seem on the cards at present).

This has all been rather discursive and perhaps self-indulgent. In (probably large) part that is because there is no easy or evident alternative, and the only paths forward for now seem to be ones where, whatever good there might have been about the US at times in the last century, things look to be getting worse, and people/countries are more vulnerable than they’d like, whether to tyrannies or to an utterly untrustworthy rogue democracy, in decline in for decades and yet spiralling worse this year with no obvious way reliably back or out. Meanwhile neither side of US politics does anything serious about the fiscal rot.

If you want some more reading on these topics, this new article in Foreign Affairs by Fishman and a couple of co-authors is interesting, if not fully compelling (seems harder than they think for the USD to be “dethroned”).