On 13 May, the Reserve Bank released its latest Financial Stability Report. As part of that release, the Governor announced that he intended to impose a ban on (highish LVR) lending secured on Auckland residential investment properties. The Bank indicated that a consultation document on the proposal would be released in “late May”.

The consultation document finally appeared yesterday. I have some fairly extensive comments on the contents of the document, and on the process. I will be making a submission, and will publish that here in due course.

But today I wanted to focus on just one aspect: the place of the stress tests the Bank undertook, with APRA, last year.

As a reminder, the results of the stress tests were reported in the November 2014 FSR (details on pages 9-11 here). The Reserve Bank was, apparently, then very happy with the resilience of the banks (individually and as a system – the latter rather than the former being the required statutory focus). As they noted:

The Reserve Bank’s emphasis tends to be on ensuring that banks have sufficient capital to absorb credit losses before mitigating actions are taken into account. The results of this stress test are reassuring, as they suggest that New Zealand banks would remain resilient, even in the face of a very severe macroeconomic downturn.

As I noted on 13 May, it was somewhat surprising then to find no reference to these stress test results in the latest FSR, even as the Governor was moving to impose very restrictive and intrusive new controls. I suggested that perhaps the Governor did not believe the stress tests. But if so, he owed us an explanation for why, especially in view of the fairly unconditionally positive coverage of the stress test results which he had signed off on in finalising the November report.

I was further puzzled when someone who had attended the Finance and Expenditure Committee hearing on the FSR told me that when the Governor was questioned about the stress test results and their implications for conclusions about the soundness of the financial system, he had simply avoided answering that element of the question.

However, the Reserve Bank then referred to the stress test results in responding to questions to the Herald’s personal finance columnist, Mary Holm. I covered those comments earlier.

On 16 May, there was this extract:

What does the RB think about the possibility of a property plunge. “Whether property prices could drop by half from today’s values is purely speculative,” she says. “Nevertheless, a 50 per cent drop matches some of the more severely affected economies in the global financial crisis such as Ireland.”

So they’re not ruling it out. But would such a drop cause banks to “collapse”? “The short answer is no, we do not believe so,” she says.

“The Reserve Bank conducts regular bank stress tests in collaboration with the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority. The most recent one was last year, and the results of it are featured in the November 2014 Financial Stability Report, pages 9 to 11, on our website.

“This stress-test exercise featured two imagined adverse economic scenarios over five years, one of which involved a sharp slowdown in economic growth in China, which triggered a severe double-dip recession in New Zealand. Among the impacts were house prices declining by 40 per cent nationally, with a more pronounced fall in Auckland – similar to your reader’s worst case scenario.”

So how would our banks fare?

“The Reserve Bank was generally satisfied with how the banks managed their way through the impacts of these scenarios, and we are comfortable that the New Zealand financial system is currently sound and stable, and capable of withstanding a major adverse event.”

Note that present continuous tense in the final sentence: we are comfortable “that the New Zealand financial system is…capable of withstanding a major adverse event”.

That was reassuring, but it did appear inconsistent with proposals for heavy-handed new controls on the other.

And then the following Saturday, we got some more comment from another Bank spokesperson.

“We repeat our comments from last week that the Reserve Bank was generally satisfied with how banks managed their way through the impacts of two adverse economic scenarios in the 2014 bank stress tests, which included a scenario similar to what your reader describes.

“We are comfortable that the New Zealand financial system is capable of withstanding a major adverse event, such as a collapse by up to 50 per cent of the Auckland housing market.”

These words, given to the Herald after the publication of the FSR and published less than two weeks ago, stated quite explicitly that the Bank is “comfortable that the New Zealand financial system is capable of withstanding a major adverse event, such as a collapse by up to 50 per cent of the Auckland housing market”.

And there I half-expected the matter to rest. Since policy development around LVRs seemed to be on a (rather distant) parallel track to stress-testing analysis, I half-expected the consultation document to avoid any mention of the stress-testing results at all, the Bank having reaffirmed only 10 days or so ago the resilience of the system.

But in yesterday’s consultation document, they do address briefly the stress-testing issue. Here is what they say:

The Reserve Bank, in conjunction with the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, ran stress tests of the New Zealand banking system during 2014. These stress tests featured a significant housing market downturn, concentrated in the Auckland region, as well as a generalised economic downturn. While banks reported generally robust results in these tests, capital ratios fell to within 1 percent of minimum requirements for the system as a whole. Since the scenarios for this test were finalised in early 2014, Auckland house prices have increased by a further 18 percent. Further, the share of lending going to Auckland is increasing, and a greater share of this lending is going to investors. The Reserve Bank’s assessment is that stress test results would be worse if the exercise was repeated now.

First, they note that “capital ratios” in the stress test fell to within 1 per cent [percentage point] of minimum requirements for the system as a whole. But here is how those results were described in the November FSR.

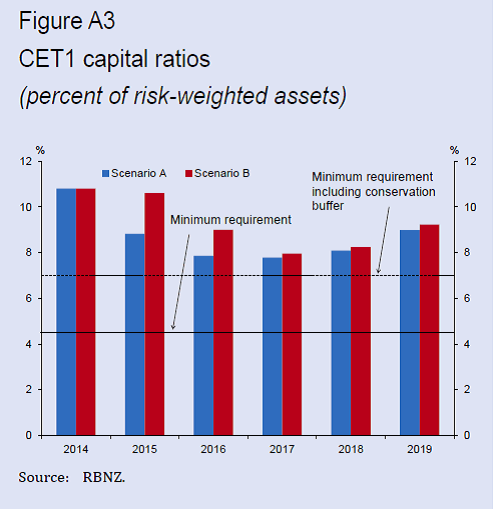

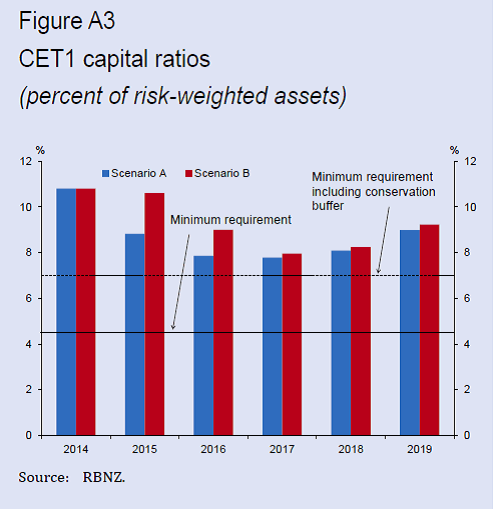

Common equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital ratios declined by around 3 percentage points to a trough of just under 8 percent in each scenario, but remained well above the regulatory minimum of 4.5 percent (figure A3). Banks are also required to maintain a 2.5 percent conservation buffer above all minimum regulatory capital requirements, or else face restrictions on dividends. On average the banking system fell within this buffer ratio in both scenarios, due to total capital ratios falling close to minimum requirements (figure A4). Average buffer ratios reached a low of 1 percent in both scenarios. As a result, some banks would have been faced with restrictions on their ability to issue dividends. The intention of the buffer ratio is to provide a layer of capital that can readily absorb losses during a period of severe stress without undermining the ongoing viability of the bank. Given the severity of the scenarios, capital falling within buffer ratios was an expected outcome.

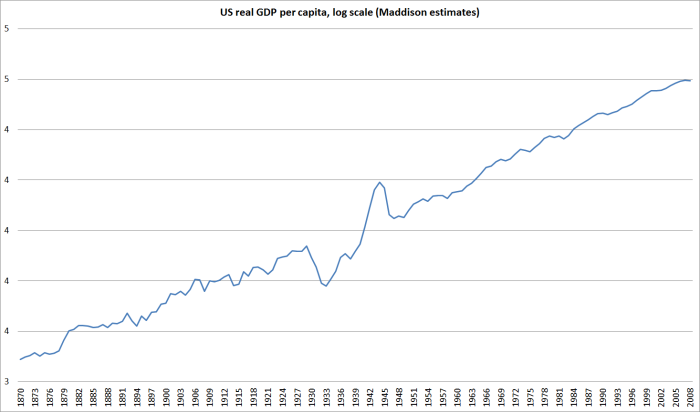

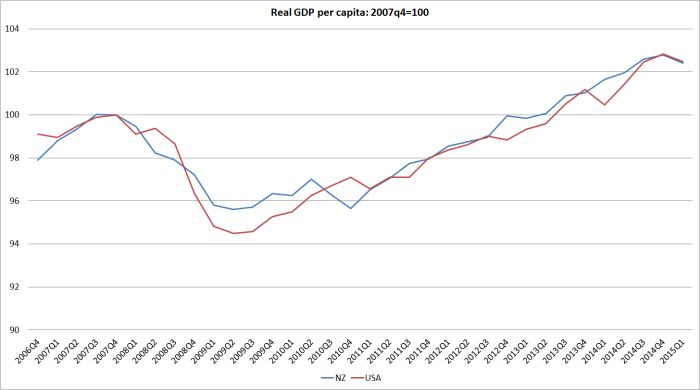

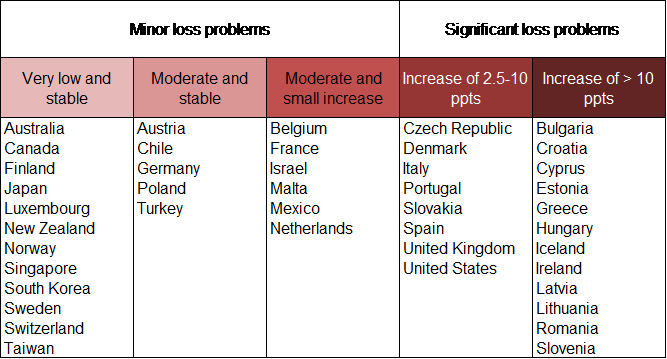

In other words, the Bank seemed pretty comfortable. As they should have been. A banking system that can withstand a very severe asset market correction and adverse macroeconomic shock with, at worst, “some banks would have been faced with restrictions on their ability to issue dividends”, while all were always above minimum required ratios (themselves calculated using risk weights that are demanding by international standards) is an extremely strong banking system. Plenty of banks abroad raised additional capital during 2008/09 without ever coming close to failure, but not one of the big New Zealand banks ever needed to raise any new capital in these stress test scenarios. But that it is what one would expect when capital buffers are large, and credit to GDP ratios have been going nowhere for seven or eight years.

As the Bank also notes, it is not even that the loan losses in the scenario were large enough to cut into the dollar level of capital banks held: the deterioration in capital ratios arises only because the risk weights on bank loan books rise in the course of the severe downturn. Not a single bank had less capital at the end of the severe stress scenario than at the beginning.

CET1 (tier one, common equity) is the focus of the Bank’s capital framework. Here is the chart from the stress test results.

The Bank also rightly notes that the scenarios for the stress tests were finalised in early 2014 and things have changed since then. Of course, they have not changed materially in the two weeks since the Bank publically reaffirmed the resilience of the system, but let’s put that detail to one side for the moment.

Unfortunately, neither the Bank nor I can easily tell what this set of facts means for the results if the stress tests were to be run today. Auckland house prices have certainly increased a lot in the last year, the share of lending going to Auckland has increased, and a greater share of this (Auckland) lending is going to investors. But other things have changed too – among other things, nominal incomes are higher than they were then, and interest rates look to be lower for longer than the earlier scenario envisaged. Those owing the large accumulated stock of debt (a stock that continues to worry the Bank) have had more time, and more income, to strengthen their own ability to handle adverse shocks.

Perhaps the much higher level of Auckland house prices now suggests that any future stress test scenario should use an even larger fall than the 50 per cent used last year. But 50 per cent is about as large a fall in house prices as has been seen, on any sustained basis, anywhere. If a 50 per cent fall is still a reasonable scenario from the new higher level (as I’d argue it is, given that no one has a good basis for knowing the “equilibrium” level of prices in the presence of ongoing regulatory constraints and policy-fuelled population growth), then all else equal there would be fewer loan losses for banks in an updated test not more.

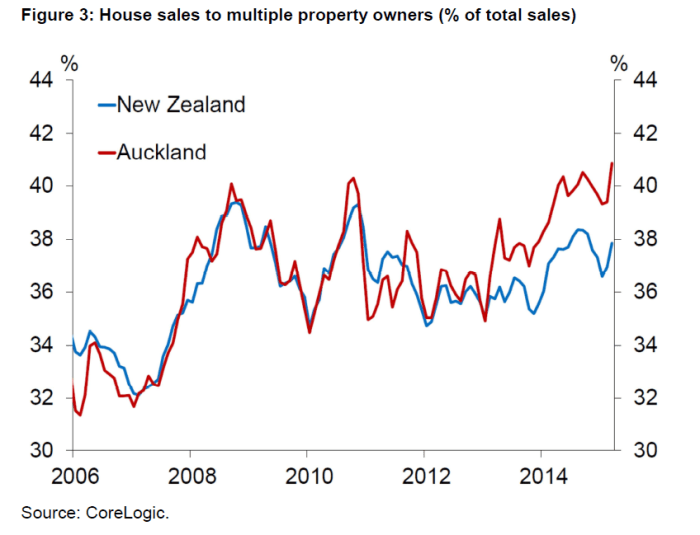

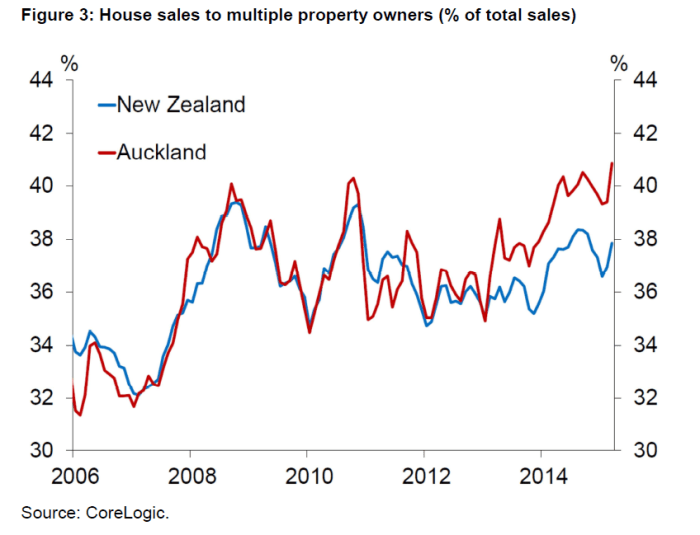

It is certainly true that a higher share of residential lending is now taking place in Auckland (although I suspect the share of the stock can’t have changed much in one year). In the stress test scenario that would, mechanically, mean a higher level of losses (since the scenario assumed a larger fall in house prices in Auckland than elsewhere). And of the lending in Auckland a little more has been going to investors. But note that final point carefully – as Figure 3 in their consultation document illustrates, the proportion of house sales being made to “multiple property owners” (the proxy for investors) is now no higher than the average in the series since 2008.

The investor property share is higher than previously in Auckland but (a) the difference from the rest of New Zealand is small, and (b) the greater role of investors is partly due to the earlier LVR restriction, which will have forced some first home buyers out of the market, to be replaced by investors. Moreover, in the consultation document the Bank indicates that the earlier LVR restriction has improved the overall “resilience” of the financial system. Even if one believed that lending to investors was riskier than lending to owner-occupiers, all other characteristics of the loan held equal (and the Bank has still not yet persuasively made that case), the overall implications of any changes in portfolio structures over the last year look likely to be small.

Stress tests run today would certainly produce different results to stress tests run a year ago. But housing loan losses have hardly ever been at the heart of a banking crisis, the stock of debt is rising only slowly, and the 2014 results were so strong that it is difficult to believe that the Bank’s analysts are seriously wanting us to believe that stress tests run today would suggest that the financial system was now imperilled. Indeed, I noted the careful way their claim was worded – they suggest that the results today would be “worse”, but not “materially” or “substantially” worse. Given how strong the 2014 results were – as the Bank itself told us – a slight deterioration, in a business so fraught with uncertainty, should not really be a matter of particular concern. Recall that in last year’s tests – an exercise to which the Bank and APRA devoted a lot of resource – not a single bank had a single year of losses. It might sound too good to be true, but it is the Bank’s own work, and “no losses” leaves rather large room for them to be wrong without the soundness of the system being in jeopardy.

Unfortunately, the Bank seems to be all over the place on this issue. It is difficult not to feel some sympathy for the staff who are required to dream up rationalisations, and explain away past robust results, to provide some support for the Governor’s strong pre-determined views. But if they really do believe that stress tests run today would result in a materially greater threat to the financial system then (a) they should probably have steps in train already to raise required levels of bank capital, and (b) it might have been helpful if they made the case in the Financial Stability Report.