Since taking office, the new government has replaced quite a number of chairs of government entities. I’m sure there are many others but NZTA, Health NZ, Pharmac, and the FMA are just the examples that spring to mind. It isn’t uncommon for such changes to be made, and in many government entities board members can be replaced at will by the government of the day.

It isn’t so for the Reserve Bank. Mostly, board members (including the chair) can only be replaced at the end of their terms. This is consistent with notions of the operational independence of the Reserve Bank, and much the same provisions apply to MPC members.

Two years ago the overhauled Reserve Bank Act came fully into effect and with it came a new Board. If the previous government appointed people who mostly simply weren’t fit for the responsibilities they were taking on (I compared them in an earlier post to a slightly overqualified board of trustees for a high decile high school), and in several cases had question marks around them, at least the terms of the appointees were staggered so that if there was a change of government there would in reasonable time be an opportunity for change. In fact, they left one possible position unfilled (the Board can have between 5 and 9 members). Perhaps most importantly, the previous chair Neil Quigley was given only a two year term (ending on 30 June 2024), much shorter than would normally be desirable but in what was clearly intended as a transitional appointment, smoothing the way with (a) a new Act, and (b) a large and simultaneous crop of new Board members.

As a reminder, the Reserve Bank’s Board is a very powerful body. They hold all the powers of the Reserve Bank other than those statutorily assigned to the Monetary Policy Committee. That means not just the corporate aspects (that the published Board minutes suggest they relish most), but all the prudential regulatory policy and supervisory powers, and most of the issues around the Reserve Bank’s large balance sheet. It also means that the Board has the primary responsibility for recommending the appointment of the Governor and of the external MPC members, and the responsibility for holding to account and overseeing the Monetary Policy Committee. These are very substantial powers, and in some cases at least seem to be taken very seriously (for example I noticed in a recent set of published Board minutes that a Board member had actually been presenting to the Board the paper on a set of proposed regulatory policy changes – which seems, frankly, quite unusual, but their choice I guess).

It is no secret that things have not gone well at the Reserve Bank in recent years.

And yet late last week this announcement appeared from the Minister of Finance

Even among those with low expectations of the current Minister of Finance, it was pretty astonishing news. It isn’t really possible to get rid of the Governor – unless he had been inclined to do the honourable thing, including accepting responsibility for the macro mess, and resign – but the Board chair’s term expired just six months after the new government took office. Of the three parties in the government, the two who had been in Parliament last term – ACT and National – had both objected to Orr’s reappointment when, as his new law required, Grant Robertson had consulted them. And it was the Board, led by Quigley, that was responsible for choosing to recommend Orr. The Finance spokesman for one of the parties (ACT) had been out in public, on ACT’s official accounts, just a few weeks ago attacking Orr

And who is responsible for the Governor’s performance monitoring and accountability? Why, that would be the board, with typically a leading role played by the Board chair.

But never mind says Nicola Willis (presumably with the endorsement of the entire Cabinet), let’s give Neil yet another two years. Either the government thinks things at the Reserve Bank are going swimmingly or (much more likely) they just don’t care. That would be consistent with there being no sign of any change to how the MPC is supposed to work (eg requiring more openness and accountability), no sign yet of any Letter of Expectation from the new minister to the Bank signalling any sort of difference of direction/emphasis, and no sign at all of pressure on the Bank to voluntarily join in cutting its (bloated) expenditure authorised by the previous government, in an agreement that has another year to run.

It isn’t obvious that there would have been any political price at all if they had chosen to replace Quigley. It was widely expected. It was the end of his term. And so on.

And there are numerous reasons why this reappointment is bad.

One of them is that, no matter how good a person is, sixteen years on a single board is just too long (Quigley was first appointed in 2010). He has already been chair for eight years (the typical limit, for example, on government department chief executives in a single role). Even the Reserve Bank Act recognises this sort of issue: the Governor, for example, simply can’t be reappointed when his current term expires in 2028, and the same went for the external Monetary Policy Committee members who are turning over this year and next. And what of Board members?

Presumably Quigley’s time on the Board prior to 2022 doesn’t count formally against this constraint, but…..sixteen years (even as the Board’s role has changed over time) is simply too long (as is 10 years as chair, again almost no matter how good you are).

Then there is the Reserve Bank that he has presided over for the past eight years, as the power and responsibility of the Board was substantially increased. That is the Bank that has delivered as follows:

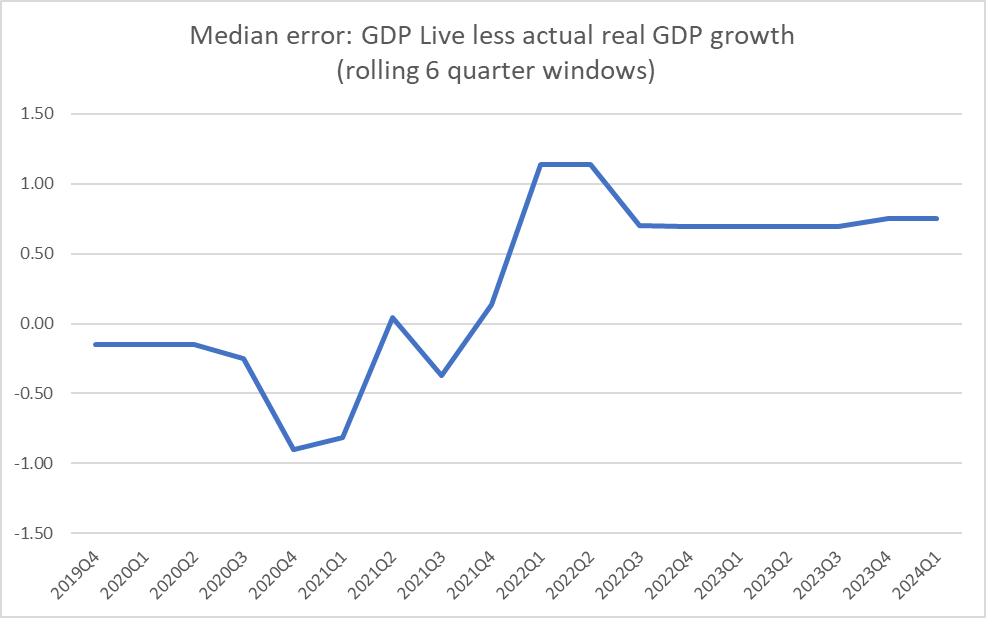

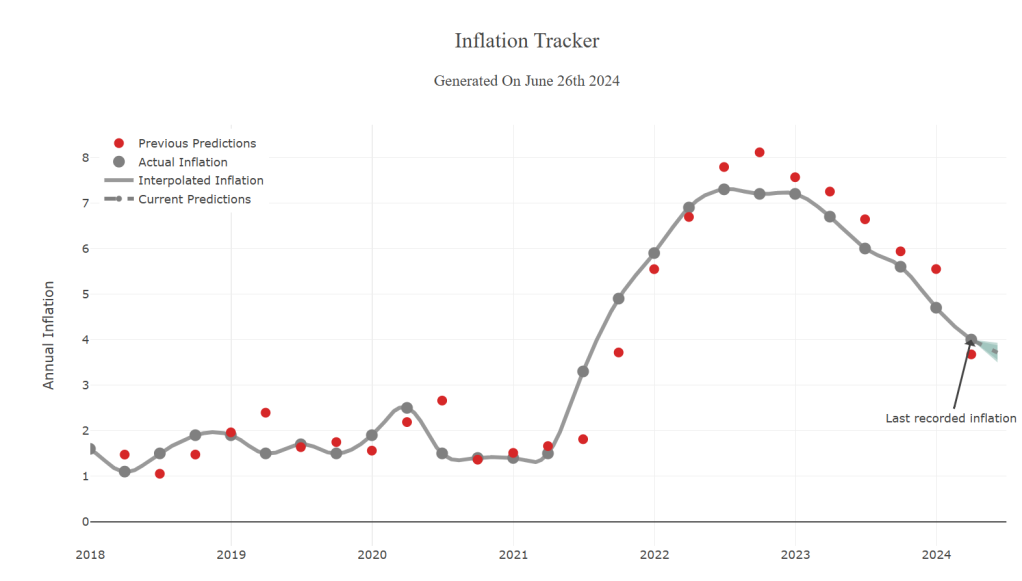

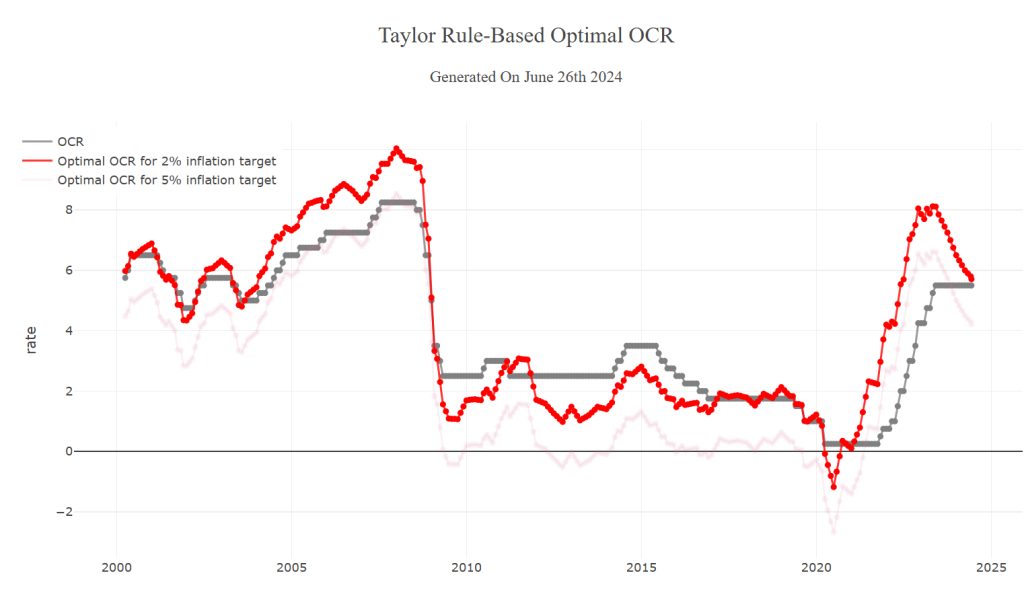

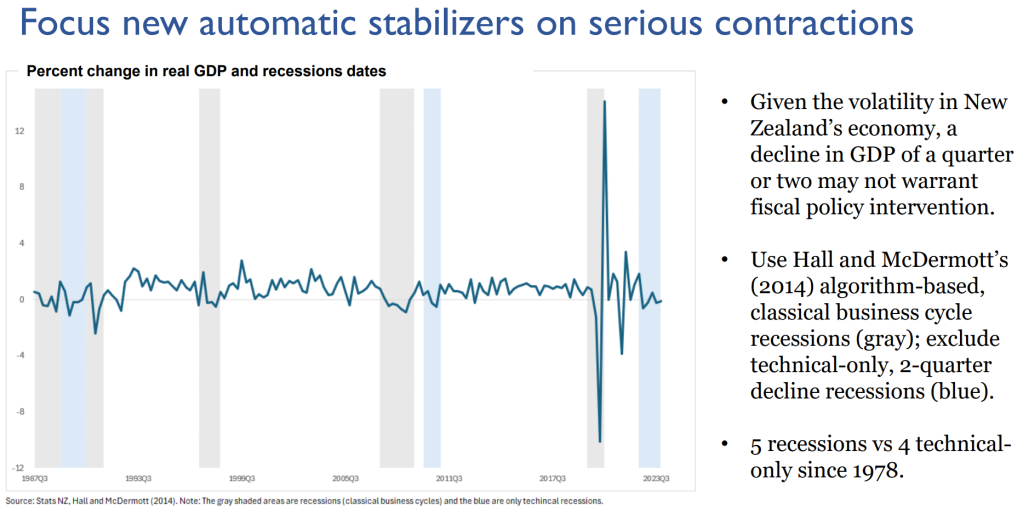

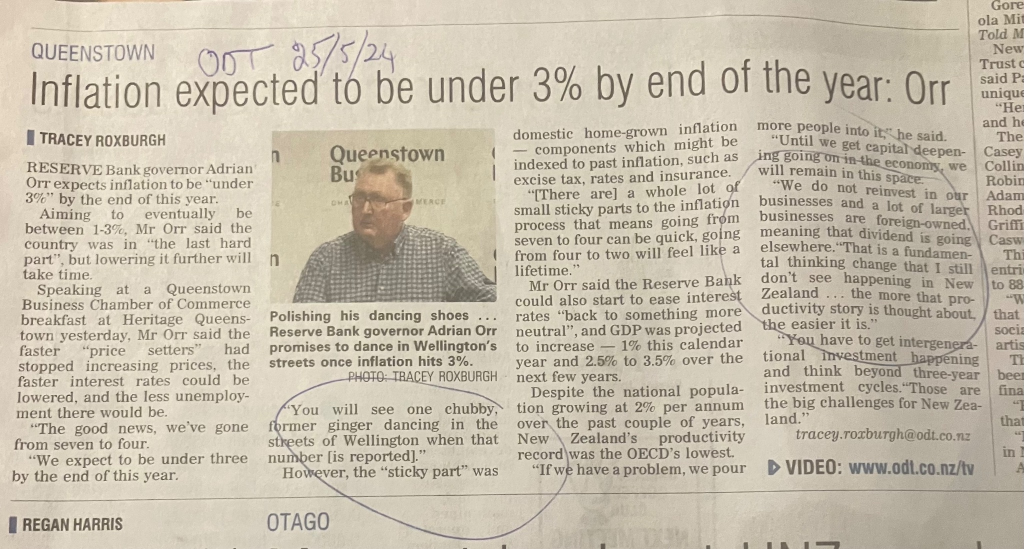

- the worst outbreak in inflation in modern times, including first the most overheated economy among OECD central banks, and now a wrenching dislocation – including deep falls in per capita GDP – to get inflation back under control,

- losses of around $11.5 billion dollars on the utterly unnecessary Large Scale Asset Purchase (LSAP) programme, with no material offsets or benefits to show for this rather reckless gamble,

- the sharp decline in the volume and quality of published Reserve Bank research and analysis (Treasury is hardly a research powerhouse but is now clearly better than the RB),

- the near-complete absence of any sort of serious speech programme from powerful senior decisionmakers,

- the blackball placed by the Board/Bank on the appointment to the MPC in its first five years of anyone with actual or future research expertise/activity in macroeconomics or monetary policy (a policy so beyond comprehension that the documents show that not even Treasury officials in the macro area understood it)

- the absence of robust cost-benefit analysis for the increasingly intrusive range of prudential controls the Bank has put in place,

- the evident loss of focus on core functions, in favour of the personal ideological preferences of management (and perhaps the Board),

- the appointment of a deputy chief executive with specific responsibility for monetary policy and macroeconomics with no background in the subjects and no evident expertise (pretty much unprecedented these days),

- a Governor who has repeatedly lied to or actively misled Parliament (eg here, here, here, and here),

- and so on.

Many of these things were the direct responsibility of the Governor and/or the Monetary Policy Committee, and it is pretty appalling that Orr himself was reappointed but (a) the Board is responsible for overseeing and holding to account the holders of these offices, and b) the Board recommended the appointment or reappointment of each of these people (the Governor himself, external MPC members to the limits the law allowed, and the utterly ill-qualified DCE who could not have been appointed to an MPC role without the Board’s imprimatur). There is also no sign that the Governor is any more willing or able to engage in a constructive manner or tolerate dissent, disagreement, or criticism than ever. He plays distraction, he plays the man. He simply isn’t a figure of gravitas commanding general respect. And he is Quigley’s responsibility.

“Public sector accountability” has increasingly become a sick joke, but Orr and Quigley are perhaps the New Zealand epitome of that. Accountability – serious practical accountability, with consequences – was supposed to be price of power and independence. Mess up really really badly and under this government (and the last) you don’t even get politely sent on your way when your term is up. This government couldn’t do much about Orr now, but they could have replaced Quigley and simply chose not to do so.

As to why, who knows? Well, the Minister presumably does but she isn’t saying (and apparently no journalists are asking). Her statement talks of two things. The first is “retaining his leadership and experience in central banking and monetary policy”, which can’t really be said with a straight face when one looks at the Reserve Bank’s recent record as a central bank (and Quigley has no direct involvement in monetary policy). The second is that his reappointment ensures the Board “is well positioned to take om new members”. Which might have been a half-plausible line in 2022, with five new members in a single day (and a new Act and responsibilities) but is a rather desperate claim now…..especially when the Minister – in office for six months already – has made no effort to fill the two possible vacancies that are there (one of long standing, the other arising 2-3 months ago when an existing director left for another government appointment), and there is an established cohort of existing directors carrying on.

The best explanation is that she simply didn’t care.

(The more hardbitten cynics might recall Quigley’s cosy relationship with the National Party over his university’s bid for a medical school (“a present for the start of your second term”), but Quigley is more of an opportunist, working whatever angles or sides benefit him, rather than some National hack – he was, after all, confirmed as chair previously by the Labour government.)

I have wondered if one possibility is that the government has someone in mind who might be suitable as chair but is either not yet ready or not yet available. Looking at the Board page I spotted this

“Future directors” are quite the thing in the public sector these days, and as this text says Grant Robertson encouraged the Board to appoint one. But they only got round to doing so on 1 June. Vermeulen, who seems to be Belgian, was a researcher at the ECB for a long time, switching to academe and relocating to New Zealand just a few years ago. He looks as though he could be a credible contender for some role in or around the Bank (possibly an MPC position, when another vacancy arises next year), perhaps even an effective Board member or even, one day, chair. It seems like a fairly unambiguously good appointment on the face of it. But then with actual Board vacancies outstanding, if this was anything like the backstory why wasn’t he just appointed straight onto the Board? If he doesn’t seem to have any much governance background, he looks no worse qualified overall than several existing Board members, and at least (unlike most of them) has some subject knowledge and expertise. So the more I think about it, the less likely my charitable explanation seems.

It is true, as the minister said, that a couple of other (underqualified) board members’ terms expire next June, but that shouldn’t have impeded replacing Quigley now – if anything it should have helped impel change at the top starting now. If Willis and her colleagues cared.

Finally, a reminder that Quigley hardly exemplifies the qualities one should be looking for in a chair of a powerful and prominent government agency, that needs to command widespread respect – not just as non-partisan, but as highly capable, honourable, and marked by the utmost standards of integrity – in return for the huge degree of influence (for good, but often for ill) that the public and Parliament grants to the Bank. The Board’s role in such an entity is to act as agent for the public, upholding all the standards citizens might reasonably expect, not to simply have the back of management and the bureaucratic institution.

Quigley can on occasion talk a good talk. But there is little evidence that he walks the talk or insists on it from the Governor or management.

On institutional capability for example, he was clearly primarily responsible for the extraordinary blackball put in place, preventing active experts from being appointed as external MPC members (a call all the more extraordinary when none of the internals were really expert either). Astonishingly, OIAed documents (finally obtained recently, when they should have been released in response to a 2019 request – now subject to an appeal to the Ombudsman) show that Quigley himself had been keen on stocking the MPC with, all things, lawyers – for a function that had almost no regulatory dimensions.

As to integrity, a series of OIAed documents last year (eg here ) show that Quigley actively asserted to The Treasury that there had never been such a blackball – this the person who himself in 2018 told an academic of my acquaintance that that person would not be considered for exactly that reason (research active in the broad subject area). And then last year – when MPC positions were being advertised again and question about the blackball were being asked – together with The Treasury he tried to suggest it was all a misunderstanding, the responsibility of some midlevel Treasury manager who had somehow misunderstood everything (and by 2023 was no longer at Treasury so was no longer in a position to push back), prompting Treasury and the then Minister to repeat his simple falsehood in public statements to the media. It was pretty despicable behaviour – against a backdrop of public comment from the then Minister, the Minister’s then economic adviser, and the Bank itself (in 2019 and 2022) defending exactly the blackball Quigley now denies ever existing. Just possibly by last year, Quigley – a busy man – had ended up confusing a couple of different things (real conflicts of interest were a genuine concern for the Board in selecting MPC members), but he made no effort to clarify the situation or acknowledge any mistake. Note that one of the other Board members from 2018/19, actively involved in the selection proceess, went on record to the Herald to (a) disagree with Quigley, b) wonder why Quigley didn’t just act to clarify things, and also, as I understand, to indicate to the Herald that they had accurately reported him.

These simply aren’t the actions of an honourable man, with any sort of commitment to the openness and transparency the Bank prefers to prattle on about rather than to practice.

On integrity, I found this line from Quigley himself in an email from 2018 (around the MPC selection process): “the Reserve Bank can never be in the situation that the integrity of its senior decision-makers could be called into question by other roles”.

Again, fine words and no one is going to disagree. But Quigley simply doesn’t walk the talk. He was active in the selection of Rodger Finlay for, first, the “transitional Board” and then the full new Board of the Reserve Bank in 2021/22 at a time when Finlay was the chair of the board of the majority shareholder in the fifth largest bank in the country. It was simply extraordinary that it happened, but nothing in the documentary record suggests that Quigley – the Board chair – ever raised much concern. It all finally got sorted out about the time the new Board finally took office, but (a) Finlay had been receiving Board papers and attending Board meetings for months while still having his Kiwibank ownership role, and b) now serves as the Board’s deputy chair, with perhaps no current conflict but still tainting the Board’s standing (and any sort of commitment to strong and honest governance in the financial system) by his prominent presence.

Then there was the case of the current Board member Byron Pepper, who was appointed to the Reserve Bank Board – with no sign of any objection by Quigley as chair – despite being then a director of an insurance company part-owned by another insurance company that was regulated by the Reserve Bank (Board) itself. It wasn’t illegal, but it was simply a poor appointment (particularly in the first up round of appointments to a new institution) and dreadful look. But not to Quigley apparently, who simply seems to have no moral sense of what is right and wrong, what is an appropriately high standard of governance, just of what can be gotten away with. Eventually, several months later, Pepper resigned from that insurance role under pressure. OIAed documents show that Quigley still didn’t think there was anything wrong but that awkward public questions might be asked and they had to worry about the pesky OIA, which (apparently inconveniently) they had to provide “good faith responses to”.

And what of Quigley own other roles? Specifically, (what always seemed like it should be a fulltime job) as Vice-Chancellor of Waikato University. Well, there Quigley and his university were recently openly reprimanded by the Auditor General for inappropriately weak procurement practices in respect of the expenditure of large amounts of public money hiring a former Cabinet minister as a lobbyist. And this was the same Quigley, the same institution, that hit the headlines a few months ago with the oh-so-cosy, but spectacularly badly phrased (particularly from someone who was at the same chair of the Board of the Reserve Bank) fawning email to National’s then health spokesperson Shane Reti, as Quigley lobbied for a new medical school.

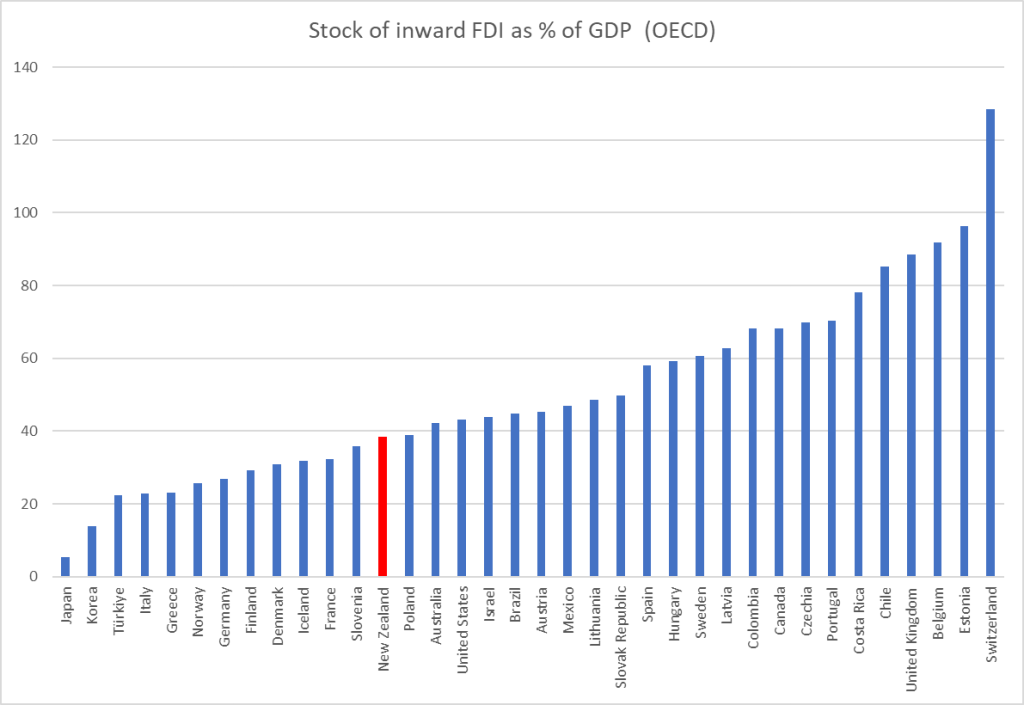

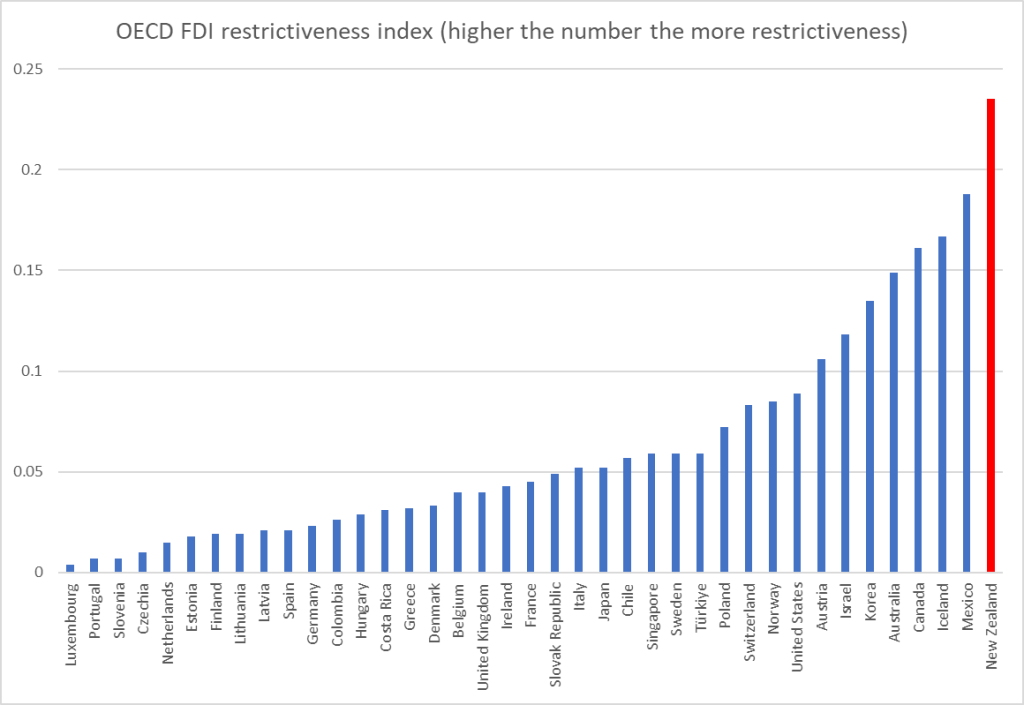

All the evidence is that, under pressure, he lacks integrity and judgement, including any fundamental sense of what is right and wrong, and what is fit and proper in the chair of a prominent and powerful public institution. He is unfit for office (an office he seems not to have exercised for any good – and if the Orr we’ve seen, blustering, repeatedly actively misleading Parliament, unwilling and unable to engage constructively, pursuing personal political agendas in public office (most recently his weird FDI remarks) is the one that has benefited from any guidance, counsel, or restraint from Quigley as Board chair heaven help us). And yet…. Nicola Willis and the Cabinet just went ahead and appointed him again.

They seem not to care at all about the decline of New Zealand public institutions (as, for example, their extraordiinary failure to appoint a Public Service Commissioner). Cynics suggested their only real interest was in holding office themselves. Sadly, evidence is mounting in support of that claim.

(But I have this morning lodged an OIA request with Willis’s office for all material relating to the Board appointments and vacancies. Perhaps some more favourable material will emerge. Time will tell, but I won’t be holding my breath.)

Note that under the amended law passed by the previous government, Willis will have been required to consult with other parties in Parliament on Quigley’s fresh appointment. Here, of course, only opposition parties matter. It will be interesting to see if any of them had comments to make – but between two mired in severe reputational (and worse) issues around their own members, and one that reappointed Orr (and the rest) in the first place, it is perhaps too much to hope for anything to have been said.

ADDENDUM

Since I hope this will be my final post about the selection of those MPC members in 2018/19 (the blackball now having been removed and some better appointments made this year), the latest set of papers the Bank eventually released again confirm how the Board under Quigley has been gaming the system to give the Minister of Finance what he (at the time) wanted. The Act is written with the clear intention that the Board selects individuals to be appointed to the MPC and recommends those specific names to the Minister. The Minister can reject such nominations, in a process that should be documented and disclosable, but (and this was a point the Bank often made in publicly championing this unusual double veto system) cannot impose his own candidates. Papers around the first selection process show that nothing of the sort happened. Even when the final recommendations went up to the Minister the Board presented him with a menu of options and invited him to choose his favourites, This was after they had already consulted him and his office, who had made it clear that they wanted at least one female appointee (even though the one chosen had no subject expertise or relevant background and may have been quite astonished at her own selection). The latest papers also reveal that late in the process a list of names was canvassed with the Minister who still wasn’t satisfied and at that point seems to have proposed that former union economist and Michael Cullen ministerial adviser Peter Harris – also with no relevant subject expertise – be added to the list. Of course, he was and was then appointed by the Minister.

To be clear, I am not a big fan of the legislated system. I would rather, as typically in other countries, the Minister was free to choose his or her own appointees to the Board and MPC and as Governor (I have previously proposed adding non-binding “confirmation hearings” (as in the UK) as some check on inappropriate appointments). But that is not the law as it stands (and was reaffirmed in the latest amendments). What we actually have is performance theatre on the public – pretending one system, practising another – all made possible by a compliant Board chair, Neil Quigley. For all his poor judgement and weak leadership, he does seem to make himself useful to ministers. But that isn’t what the chair of the Reserve Bank is supposed to be or do.