Late last week The Treasury released a new 40 page report on “The productivity slowdown: implications for the Treasury’s forecasts and projections” (productivity forecasts and projections that is, rather than any possible fiscal implications – the latter will, I guess, be articulated in the Budget documents). In short, if (as it has) productivity growth has slowed down a lot then it makes sense not to rely on optimistic assumptions about rebounds in productivity growth based on not much more than hopeful thinking. Fortunately, “wouldn’t it be nice if productivity were to grow faster” does not seem to be The Treasury’s style.

It was a slightly puzzling document though. The global (frontier) productivity growth slowdown has been around for a couple of decades now, and so is hardly news. There isn’t much (if anything) new in what The Treasury writes about that. But there also isn’t much new on New Zealand, and although there are a few interesting charts in the paper, there is very little attempt to get behind them and think about the fundamental economic factors that might be influencing those trends in the data. As an example, we are told “increasing business R&D raises the prospect of productivity benefits”, but there is little sign of any analysis of what it is that leads firms to choose (or not) to undertaken R&D spending (or spending now classified as R&D) in New Zealand. Much the same goes for business investment more generally. The decline in foreign trade as a share of GDP is noted, but it seems to be treated as some sort of exogenous event that just happened, with no attempt to offer an economic (or economic policy) interpretation. More generally, it was striking that neither the nominal nor real exchange rate gets even a single mention in the entire document.

Treasury seems to have been at pains to point out that this 40 page paper wasn’t intended as a policy document, or to address at all the much bigger issue of the huge and decades-long gap between New Zealand’s average labour productivity and that leading and highly productive economies. But they are, as they like to boast, the government’s premier economic advisers. And although they refer readers to their recent Briefing for Incoming Ministers, suggesting that “The Treasury’s Briefing to the Incoming Finance Minister outlines the Treasury’s strategic advice on the opportunities to lift productivity”, it is thin pickings there too. I hadn’t previously read the BIM (low expectations of such documents these days) but when I checked it, the main substantive document amounted to fewer than 30 pages (including lots of charts and full page headers) covering all areas of policy. There was, I think, two pages on productivity. Perhaps they tailored their product to the perceived interest of the customer (few recent governments have shown any serious interest in addressing the productivity failure) or perhaps the premier economic advisory agency just had little of substance to say.

One of my favourite (if depressing) charts over the years has been this one (where tradables here is primary and manufacturing components of GDP plus exports of services). It is doubly depressing because when I first saw it – devised by a visiting IMF mission – was in about 2005, when per capita tradables output had only just started going sideways.

This increased inward-looking nature of the New Zealand economy – across successive governments – gets very little attention in The Treasury’s document.

But perhaps what struck me most – and prompted me to write this post – was the near-complete absence of any discussion about productivity performance in those advanced economies that weren’t at the frontier (there is plenty of international discussion about the frontier, since the countries concerned are the US and a bunch of EU countries) but were or are about New Zealand’s level of average productivity. In fact, I suspect the impression a casual reader would get from Treasury’s document is that everyone has experienced slower productivity growth together.

And that is really, at best, only part of the story.

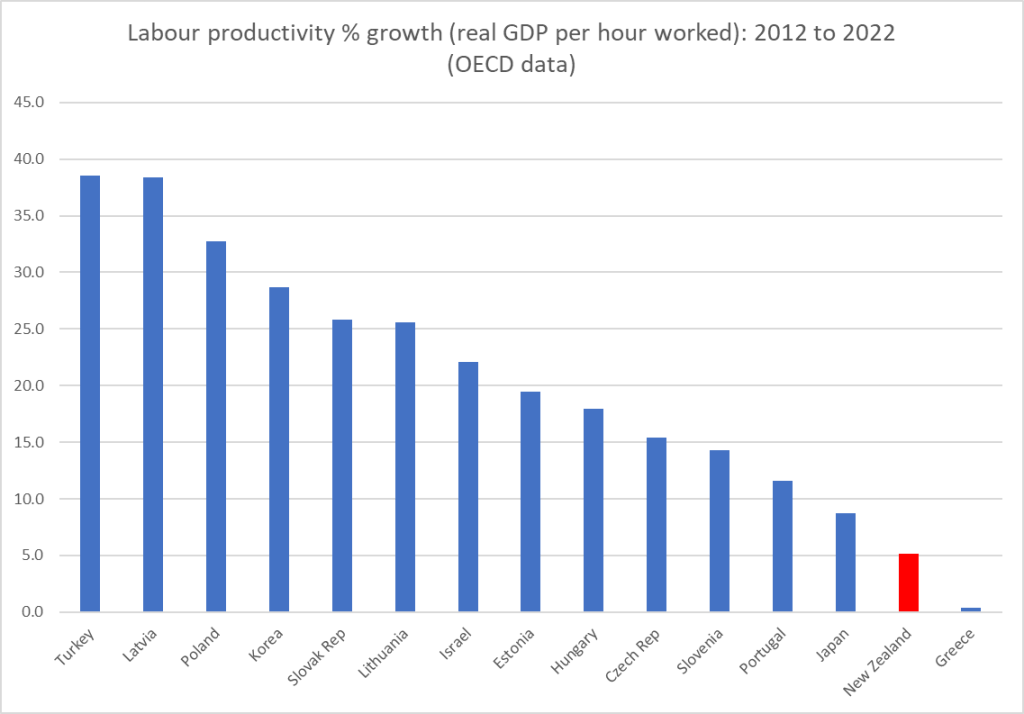

I put this chart on Twitter a couple of weeks ago

These were the group of OECD countries that had moderately close average levels of labour productivity to that of New Zealand at either the start or the end of the period. The period itself was simply a round number: the most recent decade for which there is complete OECD data.

And New Zealand has done really badly over that decade, so badly in fact that of these far-from-frontier economies, only Greece did worse than New Zealand. And these were all countries that, being far from the frontier, had – in principle – significant catch-up or convergence opportunities. More than a few of them realised those opportunities. New Zealand languished.

(Nor is there any mention/discussion of how the experience of Australia and Canada – both richer than us, but otherwise with some similarities around policy experiments and economic structures – have also had woefully bad productivity performance in the last five or so years. Perhaps there are lessons to be learned, insights to be gained?)

I’m not really sure what The Treasury’s purpose was in writing and publishing the productivity document was. But we – and I include ministers here – deserve better from the government’s premier economic advisory agency. The government having – sensibly in the circumstances – scrapped the Productivity Commission, we really need more than ever a high-performing Treasury. It isn’t obvious that we have one, or that it is being led by someone with the interest in or capacity to deliver excellence. Her term expires shortly

Again, thanks for the insights. Perhaps the folks within Treasury wrote the document with the specific intention to ‘scare/warn the horses’ via that public information so that the electorate will accept the carnage to come (economic restructure and recession). And perhaps ‘in the backroom’, they informed the minister/Cabinet of the analyses/background that you lament they did not cover in the public document.

As you suggested, Australia and Canada (altho much bigger in size) have similar welfare-state economies, such as ours, and are also experiencing bad productivity performance.

Someday, hopefully soon, we will get onto accepting that the ideals of the ‘hands off’ approach to regulatory intervention has had its day. I know that every economist I run my proposal for regulation of the residential rental market by, totally disagrees with it in principle – but these are not BAU times – no times of crises ever are;

https://www.interest.co.nz/property/119377/katharine-moody-takes-look-rental-affordability-suggesting-parliament-considers

Thinking outside the ‘box’ that we have trapped ourselves in since the 1980s era is the kind of intellectual muscle needed. Look for example, how difficult you struggled in advocating for zero-bound/negative interest rates. That, at the time, was out-of-the-box thinking, so much so that the excuse was that ‘no one had prepared for it’. Well, I think it’s time to prepare for the totally unexpected by putting everything ‘on the table’, both the ‘speakable’ and the ‘unspeakable’.

Hope you keep publishing through the crisis, Michael as your curiosity and intellect is needed more than ever.

LikeLike

The previous Labour/Greens government and its hands on regulatory approach towards property ownership and rentals was a complete failure. Rents have risen as a result of the rampant gung ho regulation imposed by the previous Labour/Greens government.

The reality of rising costs imposed by more regulation leads to higher rents. Like any business you can’t have costs higher than incomes to have a sustainable business. If you start imposing rental caps then you start to have to look at caps on rates, caps on insurance, caps on building materials costs, caps on builders labour costs, caps on the RBNZ interest rates, caps on banks interest margins. Where does it end?

LikeLike

Thanks Katharine. PNG things take up much of my time now, so posting here is going to be patchy to say the least.

LikeLike

The productivity equation is quite simple. Produce more with fewer humans. So the reality is more robots. The argument that NZ was more productive previously we all know is by just having more sheep or more cows to increase productivity or larger farms without considering the wider implications ie damage to Climate. And also we have reached peak farming in NZ.

Elon Musk with his highly automated mega factories is the productivity dream. But as we all know there is a an associated cost with automation. The balance between productivity and profitability. Humans are flexible and they are relatively cheap. Robots are still inflexible and are expensive.

LikeLike

These sort of behaviors are becoming the rule rather than the exception (locked in an in-house deceit).

I was taken by this discussion where (it appears to me) Sir Peter Gluckman is attempting to negotiate that position?

LikeLike

Great to see you back!

And what a can of worms we all face .

Tradeable productivity, which is needed to sustain the currency is in severe decline! Years of over regulation and subsidisation of everything except exports. Accomodation supplements , Working for families ,interest subsidies and yes even school and preschool FREE lunches.

(lInterest rates differentials are very real for housing vs exporting.)

There is also the inherent tax on tradable industries of a higher exchange rate driven by interest rates that have consistently been among the highest in the OECD.The appalling balance of payments reflects and drives the above

Ask any farmer, manufacturer or any other entrepreneur if NZ encourages tradable productivity.? Many have retreated into the fragile Carbon markets as dictated by profitability.

Regulation and bureaucracy has been the growth industry along with immigration and housing.

Labours ( Douglas )promise decades back of no subsidy’s was a lie.as was the level playing field.

Those subsidies have merely been transferred largely to successive governments social goals.

The big problem with all this for NZ is that an “export led “recovery is no longer possible.

NZ no longer has the exports, manufactured or agricultural to recover Even the service industries are failing.

new How can a Government fix this??

LikeLike

Key answer to your final question involves the choice to really want to fix it, to want a much better future. There is no sign either side of politics currently does. Officials are much maligned, but officials respond to incentives: they’ll generate serious advice/options when they perceive there is a real and urgent demand for that sort of product. As it is, we get agencies like today’s diminished RB and Tsy.

LikeLike

Your comment re “ the choice to really want to fix it “ has really made me think.

Many of us have views of right and wrong ,largly based on our beliefs nurtured from child hood.But in these increasingly diverse (and secular) times there are beliefs being expressed that are contrary to the values installed in many of us

So it is coming down to those who are entrusted the responsibility of running NZ — The Government.A strong focus on economic stability, balancing the books and property rights.These are important to some,but not so important to others.The Adam Smith mantra of self interest is rife.

MMP facilitates and encourages a myopic approach. Half NZ politicians are appointed , and are not scrutinised by any ballot box. The biggest concern they all have is remaining in power.Again cynicism can lead to thinking that some of these politicians regard inflation as good for wealth transfers within the populace. Friedman called inflation a tax and we know all governments love tax!

Without strong leadership the economy will continue to wallow and decline.

You are absolutely right.

LikeLike

The banks price interest rates based on risk. Unfortunately commercial or exporting activity has a much higher failure rate which has resulted in the higher interest rates for commercial or exporting activity. The market is doing what the market does ie pricing a margin above the cost.

LikeLike

The RBNZ operates independent of the government. The higher interest rate in NZ is driven by inflation. There was a time that I was quite negative about the hawkish nature of the RBNZ and our high interest rate environment compared to most of OECD neighbours and our trading partner countries. But I have come to understand that higher interest rates is a necessary evil in keeping inflation under control. It is actually to influence the exchange rate and not just a consumption management tool. As a consumption management tool interest rates do not really work very well as there are actually more savers numerically than there are borrowers. And the amount of household debt pretty much equals the household savings.

Previously I was more keen on a variable superannuation rate to reduce consumption by increasing savings which works in a place like Singapore. But a higher savings regime from higher superannuation does not support a higher exchange rate. New Zealand imports everything because the population is just too small to manufacture large scale. If the exchange rate drops inflation will fly through the roof.

It is this automatic interest rate adjustment that makes the NZD the 11th most traded currency in the world. It is a sought after currency. The currency market relies on the RBNZ to be disciplined in its administration of the OCR. It is that confidence that makes the NZD a well supported currency. It is that confidence in the NZD by currency traders that allows New Zealanders to buy anything it wants anywhere around the world. It is a valued currency.

LikeLike

Hi Michael

Following are my reckons on NZ’s productivity.

There are 2 problems. First an economic one – NZ’s productivity paradox is easily explained and fixing the big problems is not being prioritised. Second a political one – the median voters, that determine who is in government, are getting what they voted for.

On the economic problem.

Scale and distance from markets is a very significant cost for NZ and basically stops endogenous (technology or competitive) boosts to our productivity. We are not very successful at exporting and the economy grows in line with immigration-based population growth. The parameters for growth are set exogenously to the economy. We have an economy almost solely reliant on its natural resources (geography, geology and climate). These endowments are (mis) managed using an unsophisticated concession system.

I see long lists of fixes but success requires focusing on the big stuff, which is mostly about efficiency in the provision of factors of production. Fixing productivity requires the government running structural surpluses, successful monetary and bank prudential policy management, a tax and welfare system that encourages people and capital to come to NZ and ends the ruinous effective marginal tax rates, the end of rent seeking in the management of our endowment (we should price the externalities and let the highest price win) and an economy welcoming of foreign direct investment (I wish politicians would stop conflating this with seeking capital for infrastructure projects). Michael, I know you would add a more careful immigration policy onto that list.

On the political problem.

I really enjoyed Roger Partridge’s “Crisis of ambition” opinion piece in the Herald on 18 April. He is absolutely correct. The median voter is getting what they voted for. The political groupings play a game that I call “the political game of productivity”. They have long lists of fixes for productivity that are remarkably similar but require twenty years of focus. The lists only differentiate themselves with a little more social or private distribution, finely calibrated to the concerns of the median voter at the time. But NZ’s decline continues at pace.

The most rational thing to do now is to leave the country. And that is what a town the size of Fielding or Levin is doing each year.

What is going to happen to NZ is either its social cohesion will collapse under the weight of its economic mismanagement and we will get increasing political disruption until a autocratic leader emerges. You know, the usual failed state playbook that we can see in the South Pacific nearly everywhere. Or we have a seismic, weather or biological calamity that leaves us with TINA (There Is No Alternative). I give each of these alternatives about a decade to occur.

It is just possible that civil society can communicate a real plan to the median voter who does their best not to listen. Sort of a myopic short termism has gripped them as they face dealing with increasing competition for scarce resources. They are getting what they voted for but not what they want.

LikeLike

Stimulating as always Andrew. Your list of fixes would have some overlap with mine (I assume you’d add company tax rates to your list), altho useful as much of that stuff is I doubt it will get us far without a radical rethink on immigration policy.

I’m not usually out-pessimisted, but I guess my outlook is of a muddling downward ride – relatively in economic terms, even as in absolute terms governance deteriorates further, corruption increases, and many leave for Aus (as they have been for 50 years now, and even tho Aus is hardly a stellar success story). But perhaps that is in a way more pessimistic, because it is a story of the way of the last 90 years (with few brief exceptions) just keeps on. Spain was a leading economy, and then spent hundreds of years dropping behind.

LikeLike

The FX comment reminded me of a recent leading paper the Infrastructure Commission wrote on renewables(or someone like that at least). One of the big points was that the cost of renewable wind generation per Mwh was trending down and would continue to. A chart that showed a nice line moving down over a 5 year period. Brilliant, except it looks like they used a single spot fx point in time in the calculation of cost. At least it got the nice trending line I guess.

BTW I am currently developing a wind farm but have a finance/quant background so have an appreciation of what I am saying.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Except that the winds are not blowing and energy security is being threatened so Genesis Energy will ship more coal from Indonesia and this morning we get threats of power cuts by our power suppliers.

LikeLike

[…] This article by Michael Reddell was first published on Croaking Cassandra […]

LikeLike

[…] of Croaking Cassandra as economist Michael Reddell once again tackles NZ’s woeful productivity over the last two […]

LikeLike