That was the title of a ten page piece published last week by the ANZ economics team (chief economist Sharon Zollner and one of her offsiders, who appears to be a temporary secondee from the Reserve Bank). You can find a link to the paper here.

The gist is captured in the paper’s summary

I found the first line of that final bullet rather jarring – the balance of payments not having been any sort of policy focus for decades now (really since the shift to a floating exchange rate) in 1985.

But what really puzzled me about the note was how little macroeconomics there seemed to be in it, or behind it. It isn’t that there was no interesting material in it; in fact there were a variety of interesting charts on developments and issues in individual sub-sectors, and for anyone interested in these issues it is worth a read. But I thought I’d throw in a few macro perspectives.

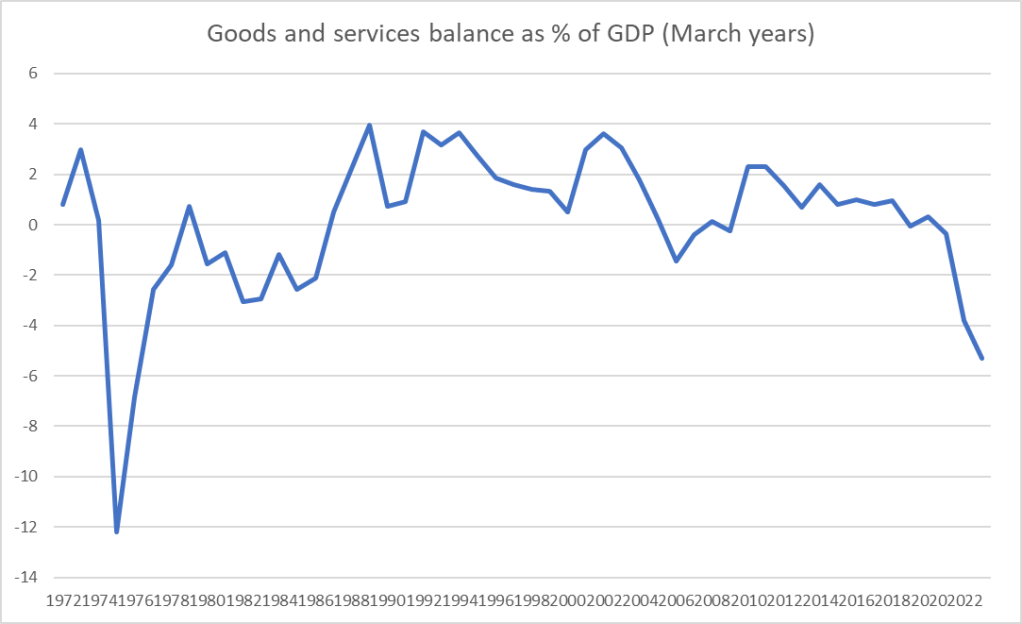

The paper starts with this chart

which is a rather different picture than the one (for the current account) we usually look at. The current deficit as a share of GDP got to about current levels in 2007, but looking just at the goods and services balance what we’ve seen in the last couple of years is without precedent for many decades. Here is the same chart with the longer run of annual data.

I’m not entirely sure why ANZ chose to focus on the good and services balance. It is akin to the primary balance in a fiscal context, which I argued here a few weeks ago it made sense to give more prominence than is often done in New Zealand for a number of reasons. If as a country you are running a goods and services balance (or surplus) it is unlikely that the NIIP position (as a share of GDP) is going to get away on you. (Of course, there isn’t anything necessarily wrong with a widening negative NIIP position – as so often, it depends what is causing the change.)

But one other positive feature of focusing on the good and services balance is that it helps to make clear that the recent sharp widening in the current account deficit – to one of the widest among OECD countries – is down to the spending choices of New Zealanders. The other big component of the current account is the income deficit (primarily in New Zealand, investment income – interest and profits). Interest rates have risen a lot in the last couple of years. But I’d have to confess I hadn’t really noticed that, thus far, the income deficit has not widened much at all as a share of GDP. If interest rates stay around current levels for long that will probably change.

So if it is spending choices that – compositionally – explain the sharp widening of the current account, where do we see that.

Well, the badly mis-forecast sharp increase in core inflation is one place. But step back a little further.

Here, from the IMF WEO database, are investment and (gross) national saving as a per cent of GDP, in annual terms included estimates for calendar 2023.

Another way of looking at the current account deficit is as the difference between saving and investment. And here you see that investment as a share of GDP last year and this has been at the highest we’ve experienced in decades (since the days of Think Big), and while the savings rate isn’t at any sort of record level it has been quite a bit lower than what we’d seen in New Zealand over half decade or so pre-Covid. Saving here is national savings – household, business, government – and we know that government dissaving – substantial operating deficits – has been a feature of the last few years, never more so than in 2022 and 2023 by when the economy was already running beyond capacity.

Beyond capacity? Well, we know the labour market has been stretched beyond sustainable (in the RB Governor’s own words) and both the Reserve Bank and Treasury have talked of positive output gaps.

But absolute numbers for local output gaps don’t get much coverage or grab the imagination. But this chart is from the IMF’s World Economic Outlook a couple of weeks back. The good thing about the IMF numbers isn’t that they are right – few forecasters consistently are – but that they take a fair common approach across a whole bunch of countries. And on their reckoning even this year on average the New Zealand economy is seen as the most overheated – “overheated” means prone to larger than usual balance of payments deficits and higher than usual inflation – of any of the advanced countries they do such estimates for. And that without any surge upwards in the terms of trade of the sort we were enjoying when the economy was last this stretched – in output gap terms – in 2007.

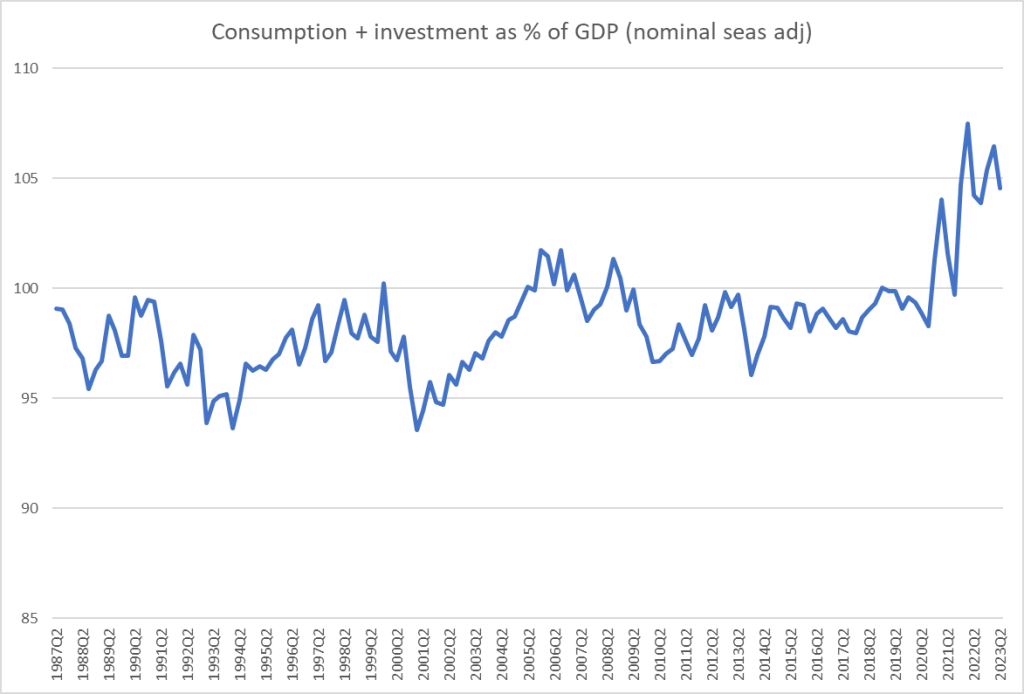

And then here is another chart I’ve shown before to highlight just how unusual domestic demand has been here in recent years.

Domestic demand needed to increase to some extent to fill a void left by the slump in net exports (most notably net services exports) if the economy was to remain fairly-fully employed, but policy (mostly monetary policy, which takes fiscal policy as given) was set so badly that we’ve ended up with astonishing levels of domestic spending, and with it……high core inflation, and a really marked widening in the balance of payments current account and goods and services deficits.

But, and here’s the thing, we still do not need specific balance of payments. Not from government, and not even from you and me thinking we’d best do our bit for the nation. Rather, as the government (eventually) gets the deficit back down again, and as the Reserve Bank eventually does its job, we can expect these imbalances largely to sort themselves out, and certainly not to end up posing severe risks to anything much. And if perhaps Chinese tourism exports never fully recover, we can expect private domestic spending to adjust, as it tends to when (for example) the terms of trade fall and people find themselves less well off than they had thought.

Of course, we shouldn’t rule out an exchange rate adjustment at some point, but we’ve come to forget how common they used to be in New Zealand – common, without being highly disruptive or prompting higher interest rates again. For a couple of decades at the RB we used to spend huge amounts of time trying to make sense of some of the biggest real exchange rate swings in the advanced world…..and then they just stopped (the reasons for that aren’t, I think, well understood or even extensively studied).

The ANZ paper ends with this line

The bottom line is, ‘something’s gotta give’, as the saying goes. We can either be the collective architects of that change or we can wait for changes to be imposed on us by foreign creditors and

financial markets.

That seems overwrought, but we should expect our macro policymakers to do their jobs rather better than they have in the last 3 years or so. But perhaps it isn’t the done thing for market economists to call out policymakers too vocally?

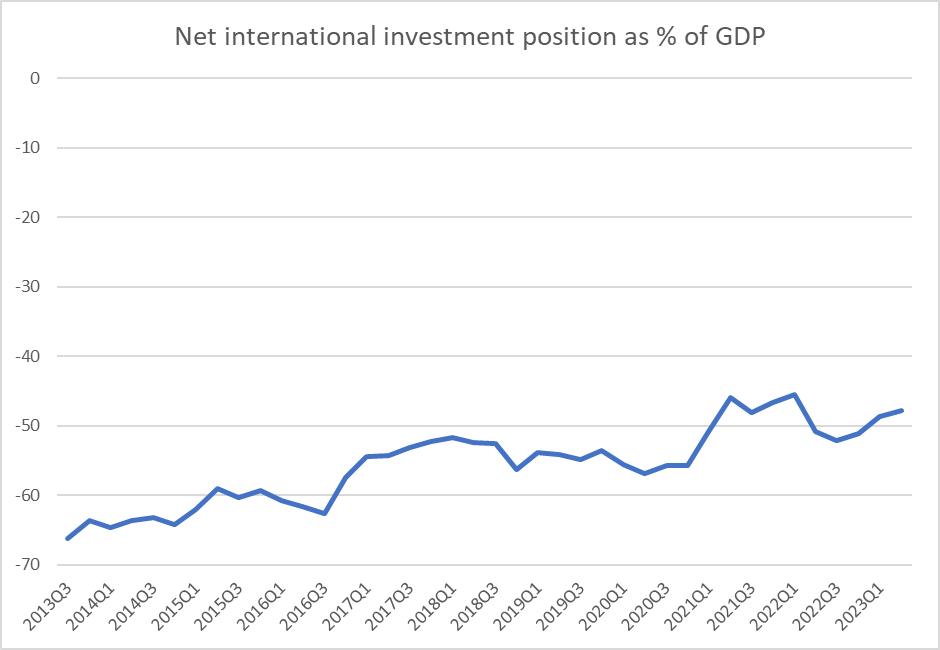

UPDATE: Oh, forgot to include this chart, which does put the last couple of years’ external imbalances in some perspective.

The rest of the world’s net claims on New Zealand residents have, if anything, shrunk a little further as a share of a GDP over the Covid years. It seems unlikely the creditors will be dunning “us” any time soon……which is not to say that if our interest rates end up lowish relative to the rest of the world there might not be some fall in the exchange rate.