I did an interview with Mike Hosking this morning on monetary policy and inflation, against the backdrop of this afternoon’s Reserve Bank Monetary Policy Statement. Where we differed seemed to be around wages. Hosking asked how did wage inflation get so high, contributing to the ongoing inflation problem, and suggested that wage earners should now hold back in order to help bring inflation down.

Such lines aren’t unknown, even from central bankers (the Governor and other senior Bank of England people have run such lines recently, and not emerged well from the experience). I think they are almost entirely misplaced. Inflation (well, core inflation anyway) is a monetary policy failing, a symptom of persistent excess demand across the economy (for goods, services, labour, and whatever). One symptom of that excess demand was the incredibly tight labour market – record low rates of unemployment (not supported by microeconomic structural liberalisations) and firms crying out for workers, reporting extreme difficulty in finding them etc. All those pressures appear to be beginning to ease now, but employment growth has been very strong even recently, the unemployment rate is still well below most serious NAIRU estimates, and the participation rate is far higher than it was pre-Covid.

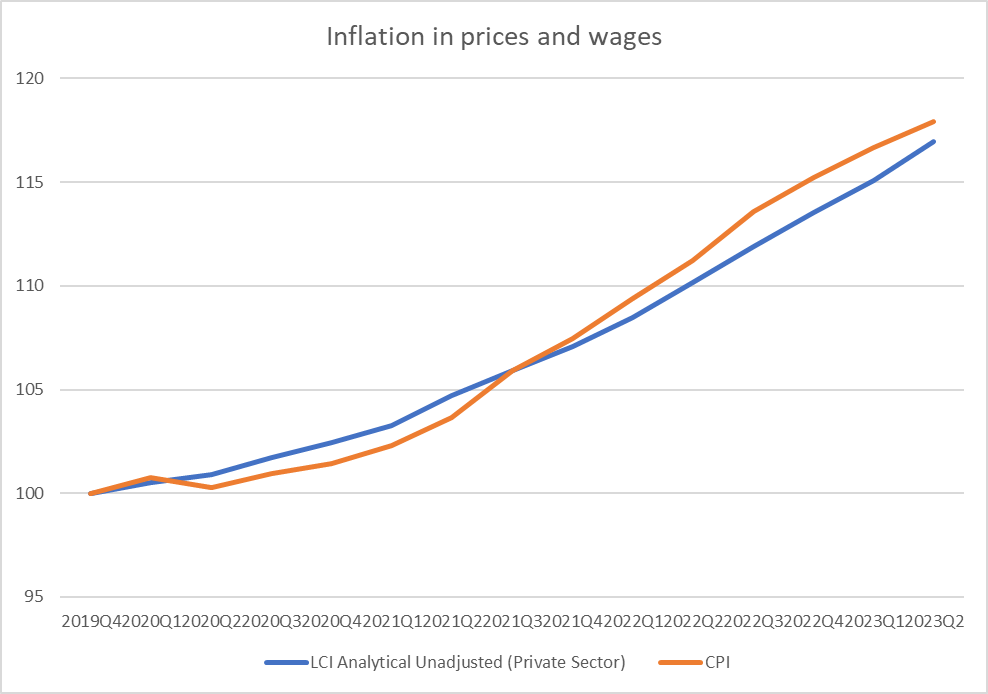

If anything, it is surprising we have not seen stronger growth in wage rates. Here is a simple chart showing wages (the stratified LCI Analytical Unadjusted index of private sector wage rates) and prices (the CPI) since just prior to Covid.

Over that 3.5 year period real wages have hardly changed (in fact they are slightly down, but the difference at the end of the period is less than 1 per cent). Even allowing for the fact that the inflation took everyone by surprise – most notably the central bank and its MPC – it isn’t really what I’d have expected this far into an inflation shock. Note that over time you’d normally expect real wages to rise as trend productivity improves, but the best estimates so far suggest little or no economywide productivity growth in New Zealand over the Covid period.

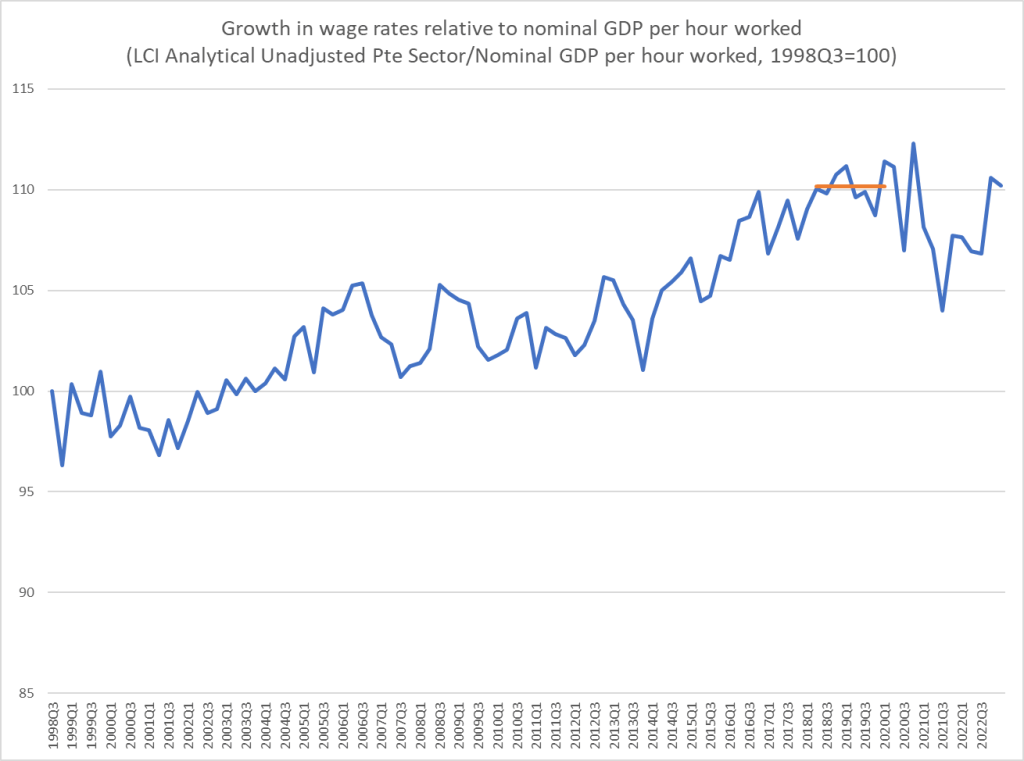

Now, as I noted in yesterday’s post the terms of trade for the New Zealand economy as a whole have been falling, reducing purchasing power relative to the real output of the economy. Perhaps wage rates have been doing something unusual relative to overall capacity of the economy to pay?

In this chart, when the line is rising (falling) private sector wage rates have been rising faster (slower) than nominal GDP per hour worked.

The orange line is the average for the couple of years immediately prior to Covid. As you see, the final observation (Q1 this year, as we don’t yet have Q2 GDP) is almost exactly at that pre-Covid level. Wage rates have not risen in any extraordinary way relative to the either prices or overall economic performance in the last year or two.

The gist of Hosking’s question was that if only workers now took lower wage increases the adjustment back to low inflation might be easier. At one level, I guess it just might, but only in the same way as if firms decided to increase their prices less (the CPI is, after all, ultimately just a weighted average of firms’ selling prices). But things don’t work like that, and it isn’t even clear that they should (there is a lot to be said for decentralised processes for both price and wage setting). As I noted in response, the labour market these days mostly isn’t a union leviathan confronting a combined employers’ leviathan, but a decentralised process in which individual firms and their workers make the best of the situations they find themselves in. Firms want/need to attract and retain staff and have to pay accordingly, and when employees have other options they can either pursue them or suggest they need to be paid more to stay where they are.

Core inflation is an excess demand phenomenon, which can be reinforced to the extent that people (firms, households, whoever) have come to fear/expect that inflation in future will be higher than it has been in the past (and whatever weight one puts on them that is what inflation expectations surveys are now showing). What we need isn’t firms or workers to be showing artificial “restraint” but the central bank to do its job, to adjust overall demand imbalances in ways that once again delivers core inflation sustainably near 2 per cent. Unfortunately, that can’t just mean heading back to things as they were at the end of 2019 when inflation was low, on the back of years of low inflation, but rising: achieving the reduction from 6 per cent to 2 per cent is the dislocative challenge.

Changing tack, as I mentioned yesterday one of the key things I will be looking for in the MPS today (more or less regardless of what immediate policy stance the Bank takes) is evidence of engagement with the question of why (core) inflation has come down so much in some (by no means all) other advanced economies and not in New Zealand.

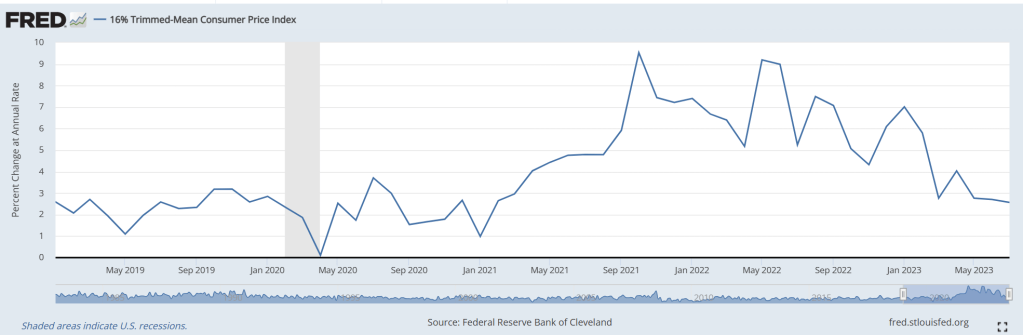

To illustrate, here is the US trimmed mean CPI (monthly annualised)

The weighted median series looks much the same.

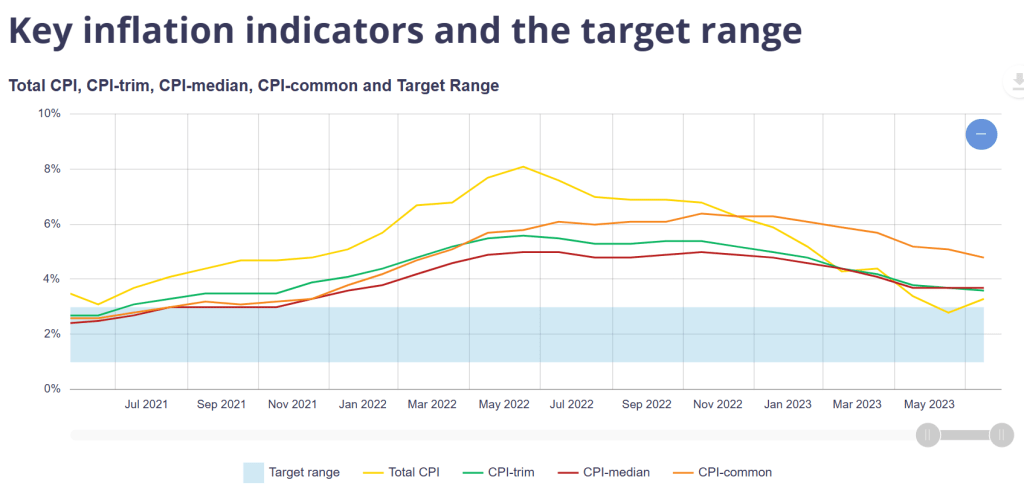

And here are the Bank of Canada’s annual core inflation measures

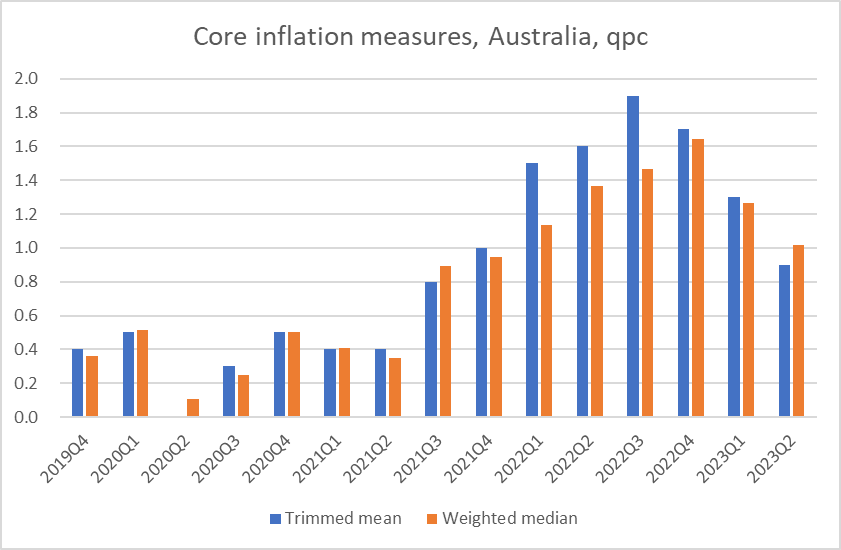

But it isn’t only in North America. Here are the Australian core measures (both now showing much the same story)

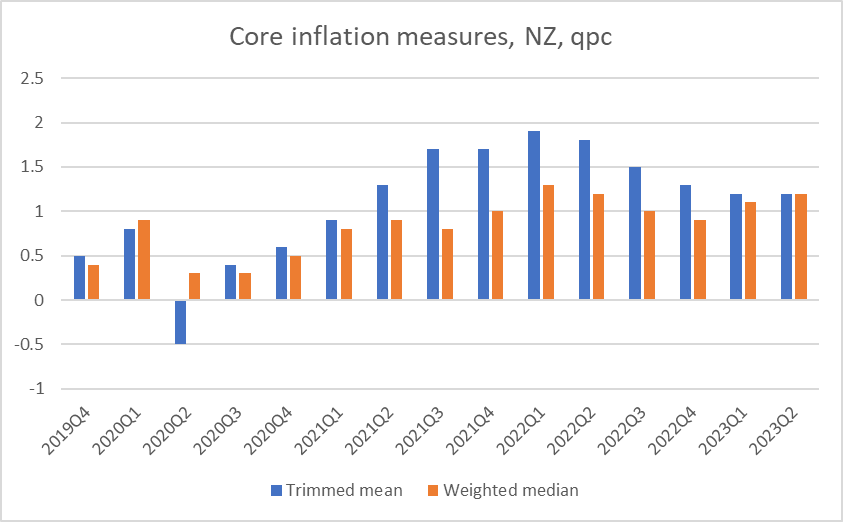

And yet here are the NZ measures

The trimmed mean appears to have fallen from a peak 18 months ago, but is hardly falling at all in the last couple of quarters, while with the weighted median it is not clear that there has been any reduction at all. Both are at levels a long way from the target midpoint.

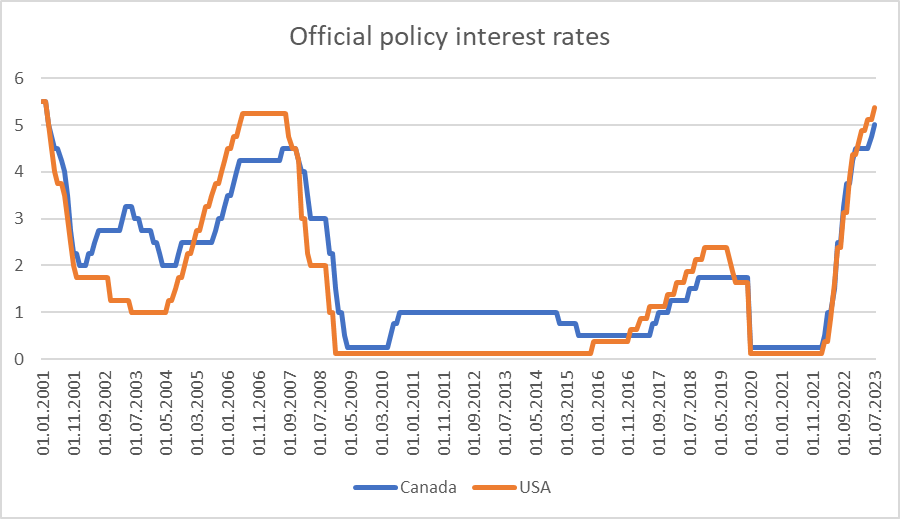

At one level, perhaps the US and Canadian inflation reductions are less surprising. Their central bank policy rates are now at or above the pre 2008 peaks. By 21st century standards these are now high interest rates for those countries

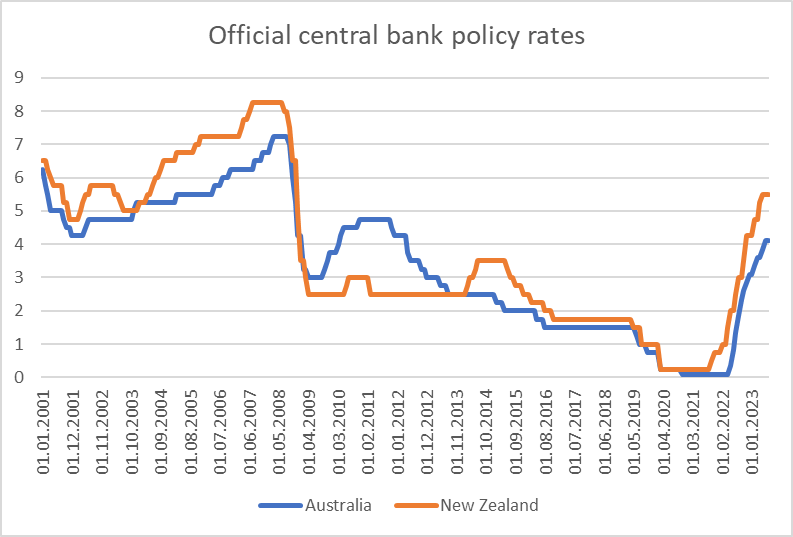

New Zealand makes quite a contrast……but Australia even more so.

I don’t understand quite why core inflation has already clearly come down in Australia at what seem to be quite modest interest rates. If you look carefully at those core inflation charts you will notice that core inflation started rising two quarters later than in New Zealand, and now seems to be clearly falling more and sooner.

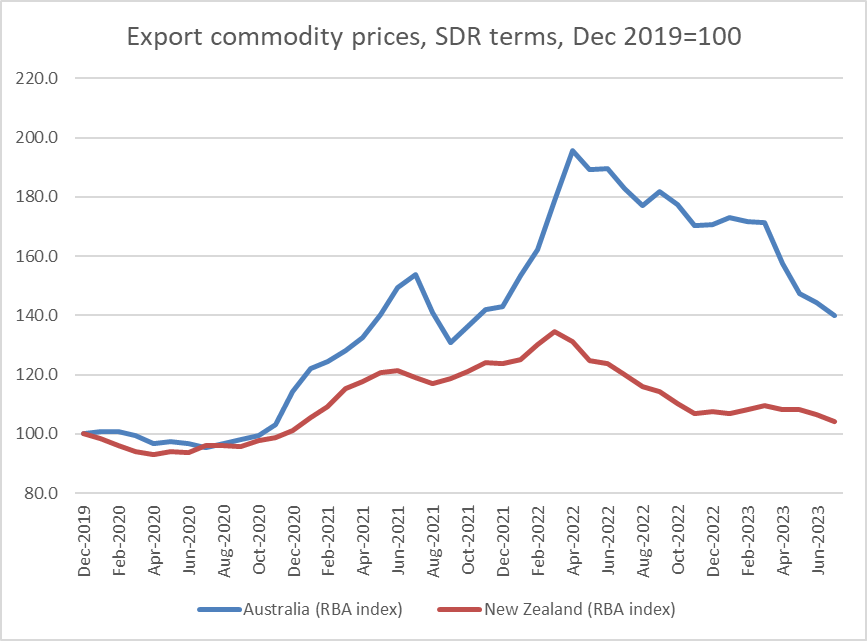

Relative to New Zealand, Australia has had a better run with commodity prices

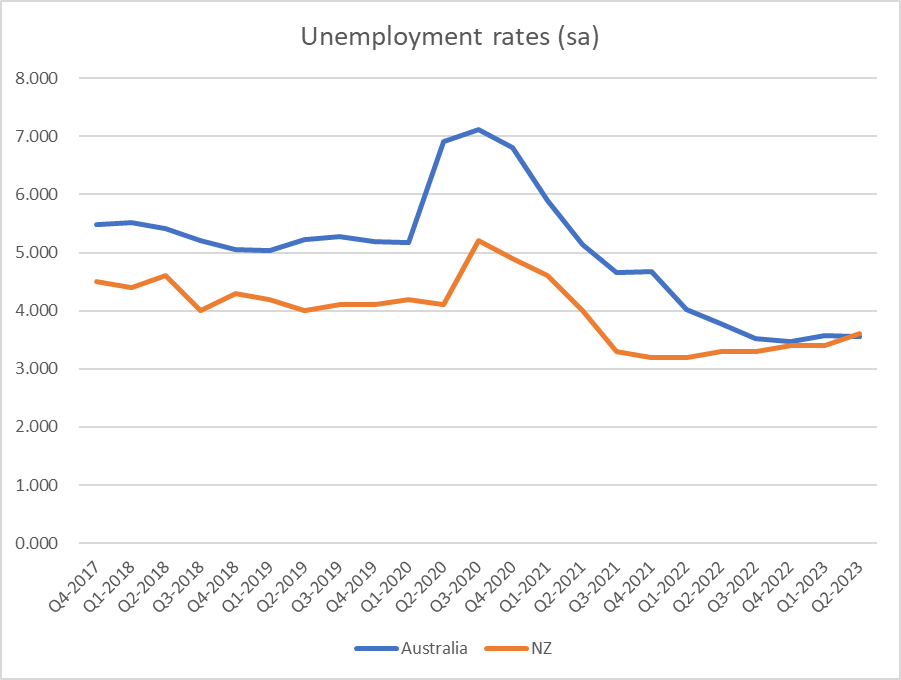

And whereas Australia usually has a higher unemployment rate than New Zealand, at present they are roughly the same, suggesting that if anything Australia may have an unemployment rate further below NAIRU estimates than New Zealand does.

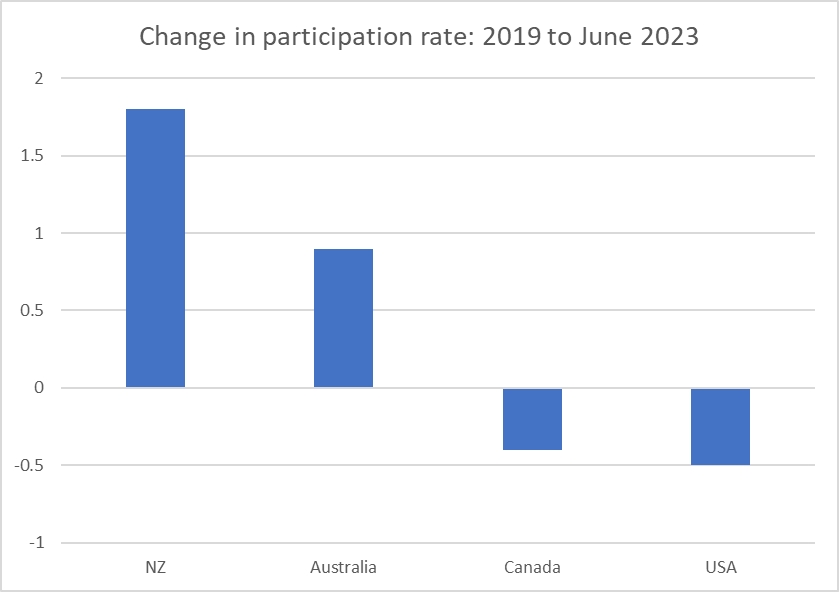

There must be good explanation for what is going on, for why core inflation has not yet fallen (as it has not in some other advanced countries) but to be persuasive such explanations need to be able to encompass credible explanations for why things have gone better (inflation fallen earlier and faster) in the US, Canada, and Australia. Those stories matters: on the face of it, the US and Canadian comparisons might suggest that the RBNZ has simply not done enough, but the Australian comparison (in an economy with a very similar Covid experience, and also a more similar labour market experience) might reasonably suggest the opposite. One sees stories from the UK and North America ascribing inflation to the low post-Covid participation rates, and (in the US) some easing in inflation perhaps being down to a recovery more recently in participation. But of these four countries NZ stands out as having the largest rise in participation (true even if some might discount the latest quarterly rise) and apparently (thus far anyway) the stickiest core inflation.

Perhaps the explanation will eventually be shown to have been some mix of “the cheque was in the mail” and “New Zealand data were published more slowly and infrequently than many other countries” – plenty of places already have July inflation data, in some cases July unemployment data, while we have only mid-May inflation and unemployment data, and have a two month wait for more.

Or perhaps there is more of an economic story. I hope the Reserve Bank can offer some serious analysis this afternoon.