For the first 20 years or so of inflation targeting in New Zealand, there was a near-constant hankering for other instruments to “help out” monetary policy. In the early days of getting inflation under control, it was little more than ritual incantations (the team I ran included them every month in our papers to the Minister) that it would help, adjustment would be easier, if only there was labour market deregulation, reduced trade protection, and tougher fiscal policy. In the Brash years, his colleagues became very familiar with the Governor’s hankering for what we (or he) called “tweaky tools”, things that at the margin might make a difference, particularly perhaps in easing the exchange rate pressures that used to be such a feature of New Zealand monetary policy tightening cycles. There was even the pesky visiting US academic in the mid-90s who used his public lecture to suggest that discretionary fiscal policy should be handed over to the Reserve Bank (we winced). It wasn’t so different in the pre-2008/09 Bollard years. At the then Minister’s urging we and Treasury ran an entire Supplementary Stabilisation Instruments projects in 2005/06, culminating a year later in a scheme for a discretionary Mortgage Interest Levy, a scheme the then Minister was tantalised by, sufficient to consult the Opposition, but eventually shut down work on only when National walked away. At about the same time, yet another invited visiting academic was openly proposing a variable GST as a supplementary stabilisation instrument. In the same vein a few years later, Labour in 2014 campaigned on giving the Reserve Bank power to vary Kiwisaver contribution rates, to assist monetary policy in the cyclical (inflation) stabilisation role Parliament has assigned it.

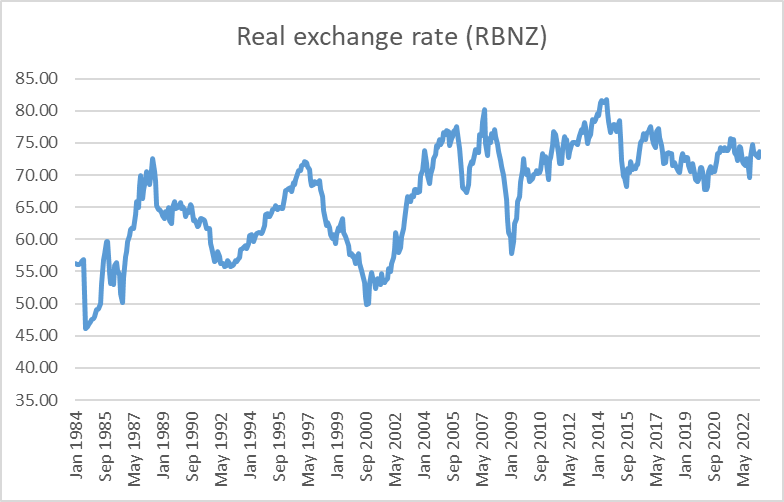

Of course, between mid 2007 and mid 2021, there were hardly any OCR increases, and those there were were quite small and short-lived (unnecessary in the first place as it happens). And since around 2010 New Zealand real exchange rate fluctuations have been much more muted than we had become accustomed to (over the decades from 1985, they were not only highly salient in political debate but also inside the Reserve Bank).

And if big cyclical swings in the real exchange rate still haven’t resumed, big OCR increases have.

And with it talk of spreading burdens, easing loads, and finding supplementary tools seems to be back. There was an article in the Herald a couple of weeks ago sympathising with indebted households who, it was claimed, are bearing the brunt of the belated anti-inflation fight.

(I wouldn’t usually be very sympathetic with people who took big mortgages when house prices were rocketing on the back of pandemic-policy low interest rates and didn’t lock in, say, five or seven year fixed rates, except that……..the Reserve Bank itself by buying up $50+ bn on longish-term government debt at the same time did rather tend to suggest to the borrowing public that rates weren’t likely to go up much – after all, which responsible government agency would expose its stakeholders (taxpayers) to a meaningful risk of $10+bn of financial losses.)

And that prompted Don Brash to enter the conversation, reviving a call he had first made in 2008 and suggesting that the Reserve Bank be given the power to vary the petrol excise tax as an additional counter-cyclical tool to assist monetary policy and spread the burden. This is reported and discussed in this Herald piece today, which in turn draws from one of Don’s own blog posts. Don ends his post with this claim

But it would have the huge advantage of spreading the social effects of controlling the inflation rate.

I disagree, quite strongly, with Don’s proposal, for a variety of practical and principled reasons, and would do even on a best-case model (say, legislation limited the extent of the Bank’s discretion and revenues were properly and formally ring-fenced).

(In the Herald article, ANZ chief economist Sharon Zollner is also quite sceptical, adding this tantalisingly radical observation – topic for another post another day:

She said the more salient questions we should be asking were not what tools should we use to try to steer the economy, but rather, should we try to do it at all, given the limitations of economic forecasting? Might the costs outweigh the benefits?

Don is quite right that (as we saw last year), petrol excise taxes can be adjusted very quickly and the effects are also typically seen in retail prices very quickly. He suggests that as the price elasticity of demand for petrol is quite limited, any increase in petrol taxes will quite quickly dampen households’ other spending, in turn dampening inflation pressures. There are certainly plenty of households who are quite cash-flow constrained, but whether the effect exists to a material extent in aggregate would need rather more careful and formal review (reflecting on my own behaviour, I’m also a bit sceptical).

But even if we grant that the effect is real and, whatever the effect actually is, perhaps fast-working, there are lots of other problems. These include:

- the temporary petrol excise tax cut of 2022/23 was 25 cents a litre. As far I can see, the direct fiscal costs of that were about $1 billion over 15 months. Even if it was $1 billion for a year, that is about 0.25 per cent of GDP. And although many economists, including me, pointed out that the income effect of this cut (and the associated road user charge and public transport subsidies) was inflationary, I’ve not seen anyone suggest it was a decisive factor in explaining core inflation outcomes over the last year or so. Quadruple the effect and one might be talking more serious macroeconomic impacts, but that would require giving the Reserve Bank discretion to make much larger changes in excise taxes than any Minister or Parliament has ever made before. Sold as an explicitly temporary effect, a cyclical stabilisation adjustment of this sort would probably result in less demand effects than, say, an excise tax increase known to be permanent.

- Don Brash argues that petrol excise taxes are easy to change. Much less so (as we saw last year in the rushed package) are road user changes for diesel-fuelled vehicles). The Brash scheme doesn’t seem to envisage adjusting road user charges, but to do one and not the other – as part of a new permanent stabilisation model – would seem simply politically untenable. He also recognises that electric vehicles are becoming more of an issue than they were when he first dreamed up the scheme, but says “Admittedly, with the growing use of electric vehicles there may come a time when varying the excise tax on petrol would have little effect on aggregate demand. But that time is still some way away.” It seems likely that EVs will soon, as they should, face road user charges, but again the politically tone-deaf nature of the suggestion that the unelected central bank should be able to whack on huge tax imposts on one lot of drivers but not others (the “others” often stylised as being upper income anyway) is staggering. And if you are tantalised by a thought “oh, but we can encourage people towards EVs”, remember that any such scheme would almost certainly have to be symmetrical…….

- As Brash acknowledges, one downside of his scheme is that increasing fuel excise taxes to fight inflation will itself, at least initially, boost CPI inflation. From a central bank accountability perspective this itself isn’t fatal (the target could be re-expressed as one for CPI inflation ex indirect taxes, and the fuel excise effect won’t show up directly in the better analytical core inflation measures), but…….one of the things we know about survey measures of inflation expectations is that they seem to be quite heavily influenced by headline CPI developments (and you can be sure media will keep highlighting headline effects). We don’t have a very good sense of how those expectations are then reflected in behaviour (spending, borrowing, price and wage setting) but it is unlikely to be helpful – and especially if we were talking of $1 a litre excise tax changes)

- It is certainly true that there are plenty of cash-flow constrained households. For better or worse, however, many of the most cash-flow constrained households also benefit from formal inflation adjustments (welfare benefit indexation), which directly undercut the cash-flow argument Brash is relying on. The tendency of governments to at least inflation-index the minimum wage works in the same direction (and if neither adjustment is immediate, the central bank should be focused on medium-term inflation prospects, not one quarter possible effects).

- People are rational. The MPC meets seven times a year. Given the prospect that seven times a year, on pre-announced dates, the fuel excise would be up for grabs, behaviour will change, with people either queuing for petrol the morning of the MPC meeting, or holding off as much as possible until just after. Especially if the prospective excise adjustments are large enough to be economically meaningful (and the road user side is even more challenging if it were to be included).

- It is a long-established principle of our system of government, dating back centuries, that taxes should only be imposed and adjusted by elected Parliaments (or at very least by formulae fixed by Parliament, as with indexation). Back when the Mortgage Interest Levy (see above) was being devised (I was the key RB deviser), I recall telling Alan Bollard that I would join the marches in the streets against any notion of taxation without representation. Same should go for petrol excise tax levies. It is all rather redolent of Muldoon’s proposal from the 1970s (which was firmly rejected) for the minister to be able to do modest adjustments to tax rates for cyclical stabilisation purposes. It is the sort of argument that has technocratic appeal, but no democratic appeal. And before anyone suggests parallels, the rate at which a central bank pays interest to a bank that chooses to deposit with it is not a tax.

- The Brash proposal seems to have no framework within which the MPC should decide whether to use a fuel excise tool, and to what extent it should use one tool rather than another. Perhaps overall accountability for inflation – weak as that now seems to be – would be unchanged, but we’d be opening the door to the whims of 7 unelected people, several with very little technical expertise either, to decide whether to whack up the fuel excise tax or whack up the OCR. There are huge distributional implications from such choices, and no framework. opening the way (among other things) to extensive lobbying from vested interests preferring one rather than the other. That seems, to put it politely, unappealing.

- One of the elements of the Mortgage Interest Levy proposal that exercised our minds a lot was how to ring-fence the revenue. There wasn’t much point in an additional tax, which might dampen some forms of demand, if the prospect of that money meant governments felt free to spend more. One can devise all sorts of clever-clogs institutional arrangements, but in the end public revenue is public revenue, net public debt is net public debt, and cost of living pressures and elections are very real. This might not be an insuperable obstacle, but money pots will tempt politicians (government and Opposition).

- Brash justifies his proposal on the grounds of mitigating the “social effects” of controlling inflation. That may well be a laudable goal, but it is one for governments. This year, however, the government has chosen to run a much bigger fiscal stimulus than it had planned even at the end of last year, on a scale swamping the plausible extent of any fuel excise tax tool, at a time when inflation is still a severe issue. Had they been at all concerned, there were options, within current legislative and governance frameworks. The government chose not to take them (and to a detached observer there is little concrete sign National would really have done much different).

Some of the points above matter more than others, and some will matter more to some than to others. But overall, it seems an unappealing proposal. Actually, I’d be rather surprised if the Reserve Bank itself were at all keen, at least after half an hour’s thought.

In the original Herald article a couple of weeks ago, the author ended this way

Quite.

Interesting.

The idea for Mr Orr to be given powers to vary the petrol excise tax is truly horrifying. This suggestion is actually insane. This means that in the Socialist Republic of Aotearoa, it will probably be Greens policy anytime soon…

However, the issue that Dr Brash raises (an overvalued real exchange rate) is a serious one. The problem is that a higher OCR drives up the exchange rate, causing private sector contractions through various transmission mechanisms, which in turn actually results in government spending rising still further, in a disastrous feedback loop of doom. As Kommissar Robbo has raised State spending by $50 billion or more, the entire weight of contractionary monetary policy required to offset this insanity is falling on an already beleaguered private sector. After the kicking the economy took from Zero Covid nutjobs, the private sector has now reached breaking point.

The solution to all this sounds simple. Central and local government spending need to be cut. Alas, it is actually virtually impossible to implement such policies, in practical terms. The neo-Marxist Team of $55 million (with over half a billion “advertising” expenditure from Kommissar Robbo) simply won’t allow it.

More realistically, local and central government spending will continue to rise, and the economy will fall, relative to our trading partners. This is what is happening across the whole of Europe, turning the economies into basket cases, one at a time.

Refer to the French economy as a good example of our neo-Marxist endpoint, if National / ACT don’t cut the size of the State.

LikeLike

Wouldn’t it make more sense for the Reserve Bank to adjust up and down a land value tax rather than fuel taxes? Land value taxes are the ultimate inelastic tax (the land can not run away) so it would not affect how the market allocates resources. It would have a faster effect than the OCR. It would have better equity effects than adjusting the OCR – which has caused asset price booms.

P.S I am not saying giving the RB this ability is a good idea – I agree giving unelected officials the power to tax is dodgy… democracy is important…

LikeLike

Most land is owned by people who are relatively less cash constrained.

Reading a book on a completely different topic prompted a thought that a variable salt tax might better fit what Don was searching for. Of course, theFrench salt tax is said to have one of many factors behind their Revolution.

LikeLike

Okay, since the method of neo-Marxism is to tax us to prosperity, how about giving Mr Orr the chance to impose a tax on breathing?

Breathing is fairly inelastic. We breathe 12 – 18 times a minute. Of course, the pesky “far right” white supremacists will probably hold their breath to avoid the tax, but the world record is only 24 mins 37 seconds, so we’ll catch them in less than thirty minutes. Perhaps we could put in an inheritance tax at the same time as the breathing tax, just in case some of the alt-right types try to use the loophole of dying to avoid my utopian breathing tax?

I’d imagine Kommissar Robbo is completely ravenous right now, and can gorge on as much tax revenue as can be generated. He is completely insatiable. Go Robbo!

Remember – collectivism is kindness.

LikeLike

Indeed – the official cash rate retains a relatively sharp edge given the short tenor of most private sector debt.

Asymmetric policy remains a problem – all out response when there is a hint of deflation risk but a more measured response when inflationary risks (relative to target) are rising.

What’s wrong with a +2.0% OCR increase if conditions warrant, there is a heads up and communication is clear?

LikeLike

It is clear that taxes are too low in the Socialist Republic of Aotearoa. Kommissar Robbo gobbled $50bn odd taxes in a few sittings, using both hands, swallowing every course in the blink of an eye.

These small portions only served to wet Kommissar Robbo’s appetite. Now he is ravenous. It feels like a lifetime since Kommissar Robbo last gorged. We urgently need to raise a capital gains tax, a wealth tax, an inheritance tax and a land tax. Feel free to add your favourite flavours. We owe this much to our great leader. These delicacies should be good for a $60bn blowout buffet for Kommissar Robbo. We can trust him to feast on this revenue in one sitting, and consume it all, not leaving as much as a crumb behind! Hooray to Kommissar Robbo!

No to the salt tax! Kommissar Robbo likes to add salt and pepper to his feast when he’s gorging. A salt tax could give him indigestion. Let’s not take out gorger extraordinaire for granted.

Hooray to the Socialist Republic of Aotearoa! Hooray to the insatiable beauty of taxation!

LikeLike

Hi Michael

Changing the subject. Do you have a view on ‘strengthening competition policy’ as a monetary policy helper? It would be more long term than a ‘tweaky tool’.

Andrea – your erstwhile reply girl.

LikeLike

Hi Andrea. Nice to hear from you.

All in favour of strengthening competition generally (sometimes things touted as “strengthening competition policy” don’t necessarily actually do so) but for efficiency etc reasons. I don’t think more competitive markets are necessarily helpful to mon policy (recall the years in the 10s when core inflation persistently well undershot target, in much the same product/service markets as we’ve since). Of course, if such micro reforms aren’t much longer term help to mon pol there is certainly no reason to think they add to any mon pol problems.

The biggest challenge here and abroad for central banks is poor forecasting, basically they (and many others in the pte sector) simply don’t seem to have had the right models to adequately understand and forecast what is going on .

LikeLike

Inflation is now rampant.Today the nurses settlement 13.5%, plus the accompanying back dated lump sum payments the huge local government rate rises just a couple of government driven inflation boosts.There are a lot more but the biggest culprit is the NZ Government.

The Reserve Bank will have a real Aegean stable to clean.

LikeLike