I was filling in the latest Reserve Bank Survey of Expectations form the other day. If one ever needed to be reminded that macroeconomic forecasting is a mug’s game, or wanted a lesson in humility, all one needs do is keep a file of one’s successive entries to that survey. Coming on the back of the latest annual inflation rate of 6 per cent, it was sobering to look back at the two-year ahead expectations I’d written down in 2021 (as I happened, I missed the July 2021 survey so can’t give you my exact number, but suffice to say it would have borne no relation to 6 per cent).

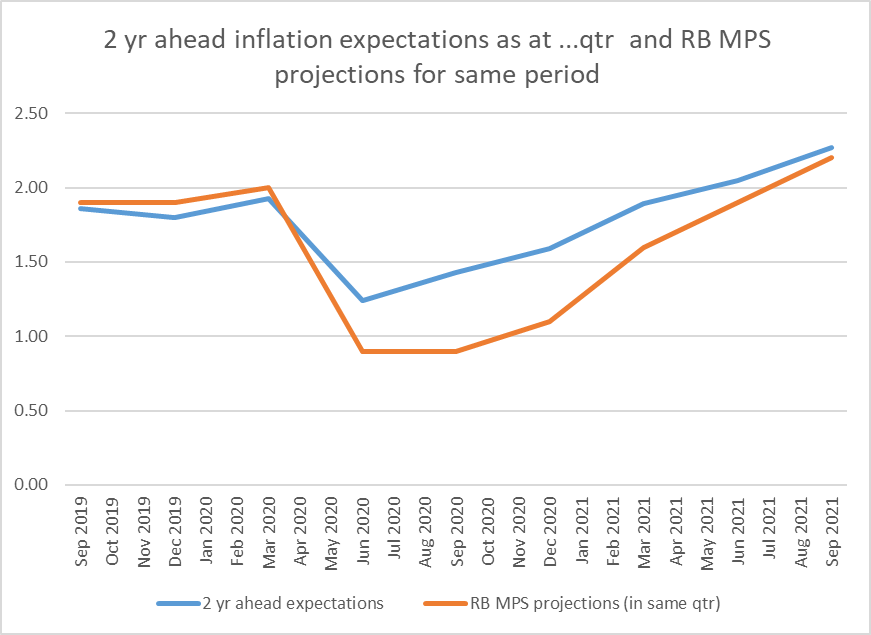

I wasn’t alone. This is what two-year ahead expectations were each quarter from March 2019 (done around the end of January) to September 2021 (done around the end of July). With something of a scare in the June quarter of 2020, the average respondent generally saw medium-term inflation sticking pretty comfortably in the target range the government had set for the Reserve Bank MPC.

As the Reserve Bank often likes to point out, these expectations measures haven’t historically had a great record as forecasts. In fact, here are the outcomes for the dates at which these two year ahead expectations were sought (so the Sept 2021 quarter survey asked about inflation for the year to June 2023). I’ve shown both the headline CPI and the Bank’s sectoral factor model measure of core inflation. Although the question asks about CPI inflation, in some ways core outcomes are a better comparator since no one is going to forecast out-of-the-blue changes in government charges or taxes, or oil prices, two years hence.

The average private commentator/forecaster who completed the surveys has been pretty hopeless.

Unfortunately for us, since it is the Reserve Bank MPC that not only makes monetary policy but is, notionally at least, accountable for stewardship and outcomes, the Reserve Bank was a little worse still

The Reserve Bank’s projections were consistently lower than those of the average surveyed respondents over the period relevant to the inflation outcomes of the last couple of years, and by margins that (by the standards of surveys like this) are really quite large. But the underlying story is even worse, because the Reserve Bank runs the Survey of Expectations so as to have the data available when making their own projections. Thus, the Survey of Expectations is open to respondents from late last week until Wednesday, but the August MPS is not until 17 August, with forecasts finalised perhaps on the 12th. The Reserve Bank has consistently more information than the survey respondents, including both the survey responses themselves and the full quarterly suite of labour market data (and other bits and pieces of extra data from here and abroad). All else equal, the Reserve Bank projections should be at least a bit closer to outcomes than the average respondents’ expectations, even if both lots of people were making the same misjudgements about the underlying story. Time has value.

The picture would be more stark again if I could effectively illustrate respective OCR expectations over the period. Both the Bank and survey respondents are, in principle, providing endogenous policy forecasts (ie both allow the OCR, and any other policy levers at the MPC’s disposal, to change), but the survey respondents are only asked about the OCR out to a year ahead (and, more recently, 10 years ahead, but that is less relevant here). And during the worst of the Covid period, the Bank wasn’t publishing OCR projections, but rather an “unconstrained OCR” path, which went quite deeply negative, even though the actual OCR couldn’t go that low. But it looks as though not only were the Bank’s inflation outlooks more wrong than the private survey respondents (answering several weeks earlier), but they were probably based on looser monetary conditions than private respondents were assuming.

We don’t know where annual inflation is going from here, or when and how quickly it will get back to around the 2 per cent the MPC is supposed to have been focused on. But if we add a couple more surveys and sets of MPS projections to the chart (bringing us up to numbers done in early 2022) it seems pretty likely that the Reserve Bank MPC projections will still have been more wrong than the private survey respondents were (after all two of the four quarterly numbers that will make up December 2023’s annual inflation have already been published). All this in the period of the biggest inflation outbreak, and monetary policy error, in decades.

I was on record last year as opposing the reappointment of the Governor (and, for what it is worth, the external MPC members). In a post back in November I included a list of 20+ reasons why Orr should not have been reappointed. None of them were the actual inflation outcomes.

I’ve tended to emphasise that both central banks (here and abroad), and markets and private forecasters, to a greater or lesser extent really badly misjudged inflation. And that is true. But central banks, and specifically their monetary policy committees, were charged with the job of keeping inflation near target, and given a lot of resource to do the supporting analysis and research. If they had done only as badly as the average private sector person over that critical period, perhaps there might be reason to make allowance (but these people voluntarily put themselves forward as best placed to do the price stability job, and are amply rewarded for it (financially and in terms of prestige). And in New Zealand at least, they did worse.

What is more, and this gets me closer to my list of reasons why none of the decisionmakers should have been reappointed, not once have we had from them (individually or collectively) an apology – for the massive economic dislocations and redistributions their mistakes led to (unwittingly no doubt, but they purport to be experts) – or even a serious attempt at robust self-examination and review, with signs that they now understand why they got things so wrong. Not a serious speech, not a serious research paper (or whole series), really not much at all (yes, there was their five-year self review late last year, but as I noted at the time there really wasn’t much openness there either). Not even an acknowledgement that they – the experts who took on the job – did worse than the respondents to their own surveys through an utterly critical period.