This blog has been a bit quiet in recent weeks (if anyone has insights on what sections 15D and 98 of the Government Superannuation Fund Act do and don’t allow I’ll be happy to hear from you) but I hope to make up for it this week.

In the 4+ years the statutory Monetary Policy Committee has been in existence, there has been not a single public speech given by any of the three external members. There have been no serious interviews either, just one petulant and testy set of responses to some emailed questions late last year, responses that I characterised at the time this way:

At times, Harris displays all the grace and constructive open and engagement we might expect in a rebellious 15 year old told they have to make conversation with Grandma at the family Christmas celebrations. If the answers aren’t quite monosyllabic grunts. most of them might as well be.

There have never been any rules against external MPC members speaking, just some mix of the Governor’s wishes and their own predilections (shy, lacking confidence in their own views, reluctant to face scrutiny, or simply not believing in either openness or accountability?) that meant it never happened. It really was quite astonishing: not only was it a new regime, which one might have thought participants might have wanted to show off at the best it could be, but we then went into a period of turmoil and fairly extreme policy experimentation, quickly followed by……the biggest monetary policy failure in decades (that high and persistent core inflation), as well as $10 billion of financial losses, for which the taxpayer (you and me) were on the hook. Surely any decent person, charged with all the power and responsibility they personally took the taxpayer’s dime to assume, would want to explain their thinking, their mistakes, and the lessons they’d individually learned.

But not Harris, Buckle, and Saunders, all three now limping towards the end of ill-starred terms in office (each having been reappointed once, they can’t be appointed again – Harris and Saunders will be gone by this time next year, and Buckle by early the following year). And we know nothing at about their views, their contributions, their defences, the lessons they’ve learned, or even any contrition they might feel. Of that latter, presumably none or surely they’d have told us. Decent journalists are only an email or phone call away. Meanwhile, we live with the inflation, the looming recession…..oh, and as taxpayers are $10 billion poorer as a result of their choices.

You’ll remember that the external members were selected in a process whereby (in the words of a Treasury paper to the Minister of Finance)

Which did tend to select against people who might either think hard or make serious and self-critical attempts to learn from their mistakes.

You may also remember a strange article a few weeks ago in which the Minister of Finance and The Treasury (but not the Bank or the Bank’s Board) tried to pretend that there had never been any such restriction. A couple of us are still waiting for responses to OIA to better make sense of quite what game Treasury and the Minister were playing there, but my post a few weeks back makes clear – from their own contemporaneous words at several points through the process- that there had in fact been such a restriction. It appears to have been removed for the next round of MPC appointments (vacancies being advertised at present), and if so that is a welcome step forward.

And somehow, one of the external members, (emeritus professor) Bob Buckle, emerged from his monetary policy purdah to deliver a keynote lecture at the recent conference of the New Zealand Association of Economists (invited, he tells us, by the council of the NZAE no less). His topic? “Monetary policy and the benefits and limits of central bank independence”.

There is 25 pages of text and more than 150 references at the end. But here’s the thing. I’m pretty sure I learned nothing from the lecture and wasn’t prompted to think harder or differently about anything.

In a way, perhaps that isn’t surprising. Buckle’s focus has tended to be on empirical macro (VAR models and all that) and some public finance and tax issues. He doesn’t have a publication record in areas around central bank independence, and has not (that I’m aware of) offered any speeches, presentation, papers or anything with interesting or challenging angles on the issue over the course of his academic career. He is, in many respects, a pleasant establishment figure (and there is a place for them) not one who will make you think about things freshly or differently.

Perhaps the council of the Association of Economists was thinking, “well, after four turbulent years as a foundation member of a Monetary Policy Committee perhaps he will offering some perspectives informed by his experience as a policymaker. After all, he done no speeches, but this will be a more academic audience, which might be in his comfort zone. And, after all, a lot hasn’t gone well for monetary policy in the last few years”. If so, they must have been disappointed.

Someone who was there sent me a message later that day

I’m no expert so cannot speak about the literature he described, but the lack of NZ content was so noticeable it was weird. Cliches about “elephant in the room” and all that. He did mention “we need to wait for full assessment” when someone asked a question about the covid monetary interventions, but he was obviously uncomfortable saying even that.

It seemed impossible to distinguish from a paper he might have written had he never been appointed to the MPC. Was there nothing he thought differently about, or understand more (or less) from having been inside the tent? If so, he clearly wasn’t inclined to tell us. And, in fact, as my correspondent pointed out there was hardly anything about New Zealand at all (I checked and there are no mentions of “New Zealand” outside footnotes and references that are more recent than about 1990).

It can’t have been just that he didn’t want to offer any thoughts relevant to the immediate monetary policy situation (where will the OCR peak and when and why?). It must instead have been that he had nothing insightful or challenging to say on his own topic (just possibly, the Governor had persuaded him to deliver something so grey and un-insightful, but (a) that would hardly be in the Governor’s interest (he is usually keen to talk up his committee), and (b) real insight shines through anyway. There was none in Buckle’s paper.

There might, for example, have been thoughts on accountability. The literature is replete with references to the importance of accountability if a central bank is to have operational autonomy. But how does Buckle think about that specifically, having been one of those who were to be (in principle) held to account, in tough times. What sort of accountability does he think really matters and why? What, if anything, made a difference to his own conduct/advice. He offers us nothing.

Or, say, on communications. What is it that convinced Buckle, now as a policymaker, that never hearing from (ostensibly) powerful key policymakers (and it isn’t just no speeches or no interviews but no select committee appearances) is the best way to run an operationally independent central bank? Again, no insight.

And if operational independence for central banks tends to reduce inflation (there is some suggestion in the literature that it may), is that always and everywhere a good thing. After all, in the aftermath of 2008/09, a whole bunch of countries went through a protracted period of inflation undershooting the target. Perhaps an inflation-happy Minister of Finance might then have been better than an independent central bank? Perhaps not, but the issue isn’t addressed (not even, more extremely, in the Japanese context). And on the other side, there is no serious engagement – even slightly speculative – on what the experiences of the last few years tell us about the case for central bank independence? The implied promise 30 years ago was that if we handed over day to day control to central bankers, we wouldn’t see core inflation of 5-7 per cent again. And yet we did. Buckle never engages much with Tucker’s criteria for delegation to expert agencies (either for central banks, or by comparison with other government activities), but it isn’t controversial that the case for delegation is stronger, all else equal, when the delegatee knows what it is doing.

There is nothing at all about whether, and if not why not, it might be important to buttressing central bank monetary policy operational independence to do something about fixing the effective lower bound on nominal interest rates.

There isn’t even any sense of an intuitive familiarity with the experiences of other countries. What, if anything, do we learn from the cases of the (very small handful) of advanced countries that hadn’t given independence to their central banks (low inflation Singapore being a prime example). These aren’t just issues for New Zealand, but he is a (retired) New Zealand academic and a New Zealand policymaker.

And so on.

There were various small things I took exception to. There were hints of Orr (misleading Parliament) in a couple of attempts to shed some of the blame for inflation onto the Russians, as if core inflation had not already reached its peak (and unemployment its trough) before that invasion

There was the somewhat surprising claim

That footnote 50 took you, among other places for other countries, to the Reserve Bank’s report marking its own homework late last year. Sure enough, when you check it the word “mistake” doesn’t appear at all (or “error”) and there is no expression of “regret” at all (you’ll recall Orr’s standard line is the non-regret regret “I regret that NZ has had to deal with a pandemic, the war etc”).

And if this paper might not have been the place to go into all that in detail, wasn’t it an obvious place to think aloud about the place for contrition (people being human, mistakes being inevitably, and some of those mistakes are very costly indeed to people who are not themselves policymakers, while often appearing to have no consequences at all for those who made the mistake) in the independence/accountability context.

One interesting line that popped up in several places during the speech was a concern about anything that might tie the hands of the MPC.

This paper suggests there are intersections between legislated objectives and operational independence that could have implications for central bank independence and the political acceptability of CBI. These intersections involve expanding central bank mandates, conditions attached to the pursuit of primary objectives of monetary policy, and funding arrangements that could influence central bank independence over the choice and scope of alternative monetary policy instruments.

That is fairly wordy, but what it means is that Buckle thinks they need to be free to lose $10 billion again on fresh highly risky financial interventions (having neither here nor in the 2022 self-review either expressed contrition for the actual losses, shown how they would do better in future, or explored whether there might be reasonable limits to the financial losses taxpayers might be willing to let unelected officials incur (almost all government spending has to be appropriated by Parliament first, but not when the MPC takes the public balance sheet for a spin)).

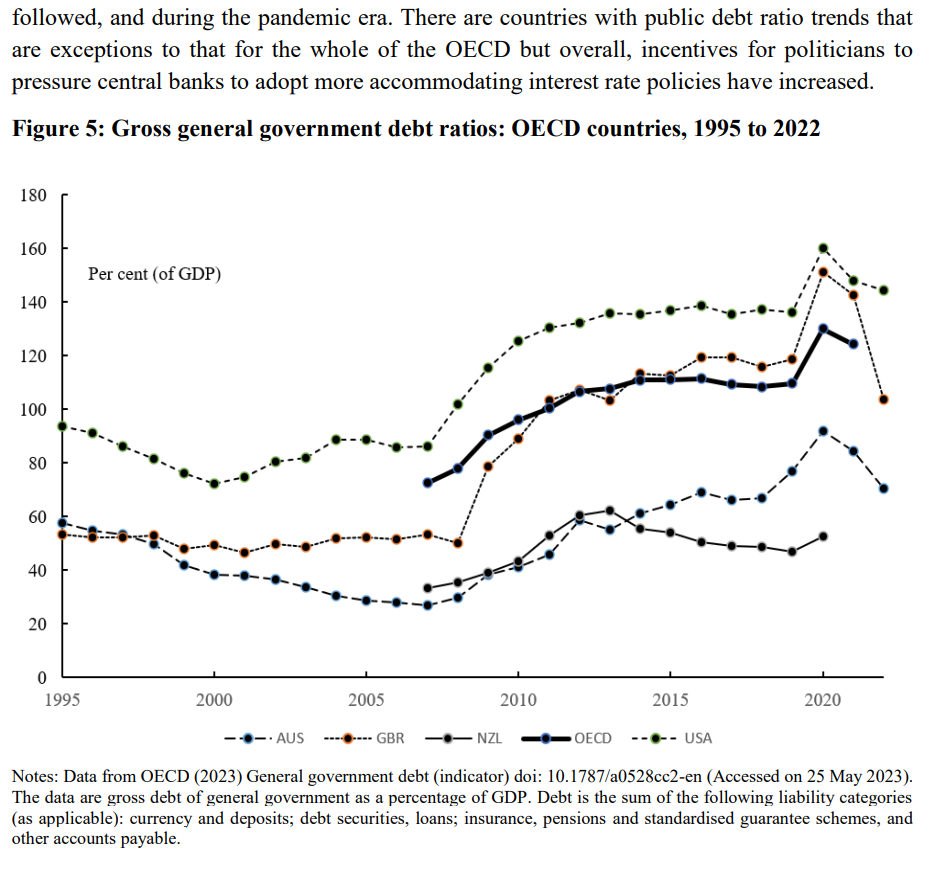

Which brings me nicely to the last substantive section of Buckle’s paper, on fiscal policy connections. It is fairly unenlightening (and reminded me of the ambitious play by the Secretary to the Treasury for a greater role for fiscal policy just before everything went to pot on inflation). But Buckle repeats, unreflectively, suggestions that central bank independence might have led to lower fiscal deficits (and seems to think this is automatically a good thing). He then suggests that times are changing and fiscal policy might be more of a threat, illustrated with this chart

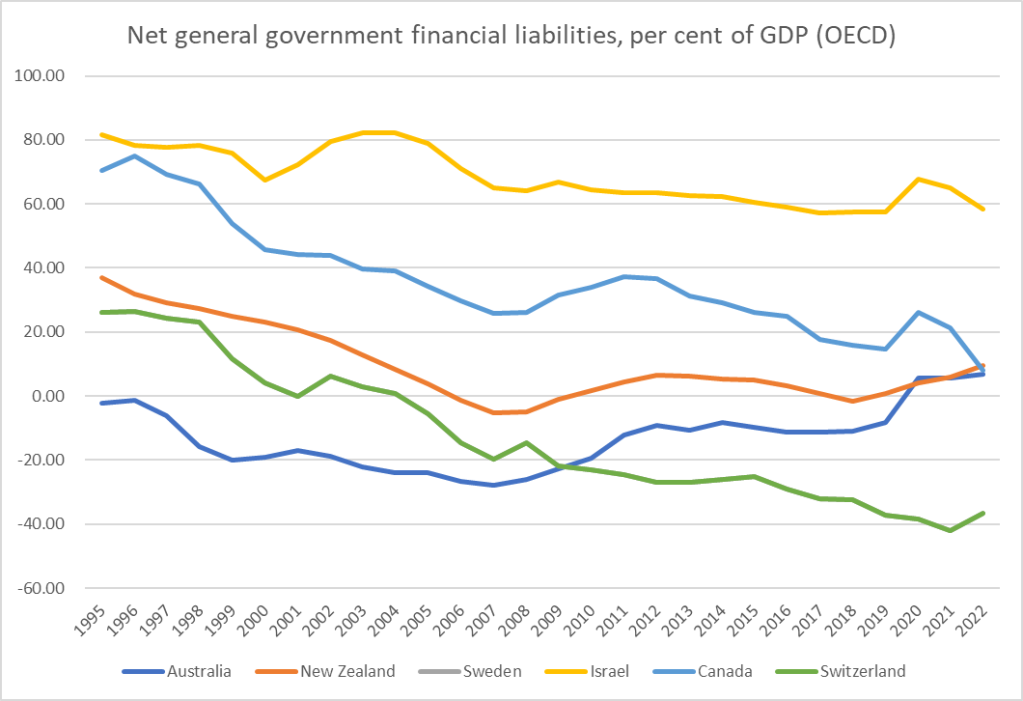

Perhaps, but here is another way of looking at things. Here is net government debt for half a dozen small to middling inflation targeters with independent central banks, including New Zealand

All these countries have pretty moderate levels of net debt, and all except Australia (barely) have had a falling ratio of net government liabilities to GDP over the last 30 years.

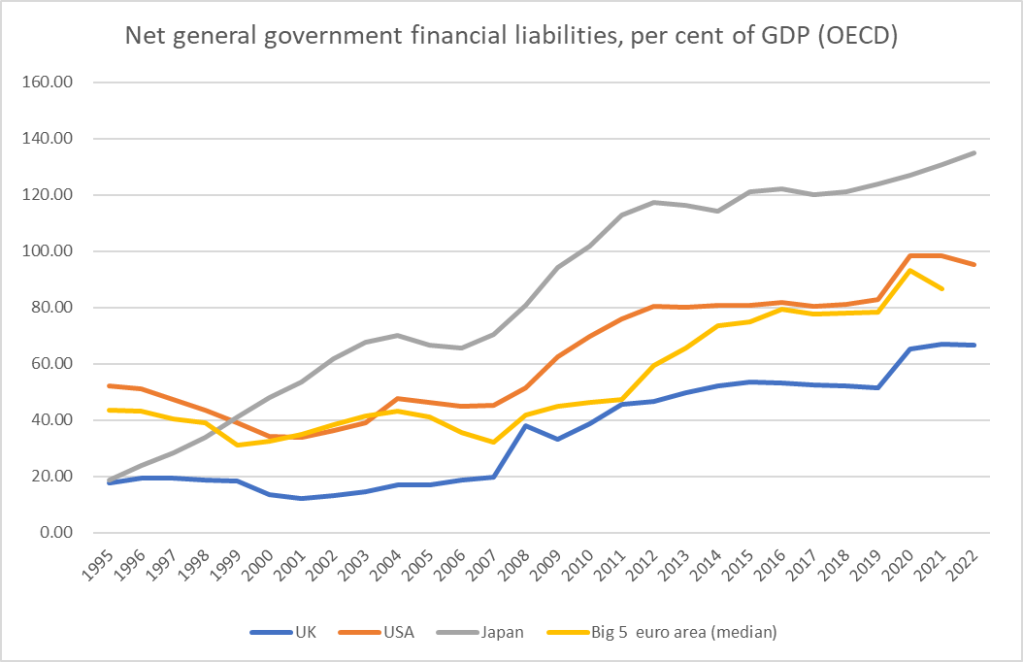

On the other hand, here are some other (larger) countries with independent central banks (in the euro area by far the most independent of any of the central banks)

All four lines slope upwards, and in all four cases debt is a lot higher than it was in 1995, early in the new era of central bank independence.

Perhaps it is fair to suggest there may be some future issues in some of these countries for central banks, but you’d have thought that a New Zealand policymaker might recognise the very wide range of country experiences (which might also make one a little sceptical that whether or not the central bank is independent explains much if anything of advanced country fiscal choices and outcomes).

No doubt there will have been some readers who got something from something like the Buckle lecture (I passed it on to my economics student son eg, and there is always a use for introductory material), but from a serving policy maker, to a premier New Zealand economics audience, it really is pretty disappointing.

Buckle is probably the least unqualified of the external MPC members, but efforts like this are a reminder of how far from the frontier of best practice New Zealand’s new MPC – creature of Orr, Quigley, and Robertson – is. One can only hope that if there is a new government that they will care enough to insist on much better (in the RB, and in so many of New Zealand’s degraded public sector institutions)>