The Public Finance Act requires that every four years The Treasury publishes a “statement on the long-term fiscal position” looking “at least” 40 years ahead. Parliament allowed them to defer the report due last year, but yesterday they published a draft – for consultation – of the report they will formally publish later this year. Quite why they have chosen to go through this additional step, of consulting formally on the draft of a report that is likely to have next to no impact even when finalised, is a little beyond me.

These long-term fiscal reports are fashionable around the world. As I’ve noted previously I was once quite keen on the idea, but have become much more sceptical. They take a lot of work/resource – which should be scarce, and thus comes at a cost of other analysis/advice The Treasury might work on – and really do little more than state the obvious. As I noted when the last long-term fiscal report was published.

I was once a fan, but I’ve become progressively more sceptical about their value. There is a requirement to focus at least 40 years ahead, which sounds very prudent and responsible. But, in fact, it doesn’t take much analysis to realise that (a) permanently increasing the share of government expenditure without increasing commensurately government revenue will, over time, run government finances into trouble, and (b) that offering a flat universal pension payment to an ever-increasing share of the population is a good example of a policy that increases the share of government expenditure in GDP. We all know that. Even politicians know that. And although Treasury often produces an interesting range of background analysis, there really isn’t much more to it than that. Changes in productivity growth rate assumptions don’t matter much (long-term fiscally) and nor do changes in immigration assumptions. What matters is permanent (well, long-term) spending and revenue choices.

And I’m old enough to remember people lamenting the potential fiscal implications of an ageing population – at least conditional on government choices – well before long-term fiscal reports were a thing.

What’s more, lots of countries have these sorts of reports, and of them some have very high and rising levels of government debt, and others don’t. It isn’t obvious that access to these sorts of long-term reports really makes any difference at all (see, for example, the US, with a rich array of private and public sector analysis – although do note that the US is well ahead of us in raising the eligibility age for Social Security retirement benefits).

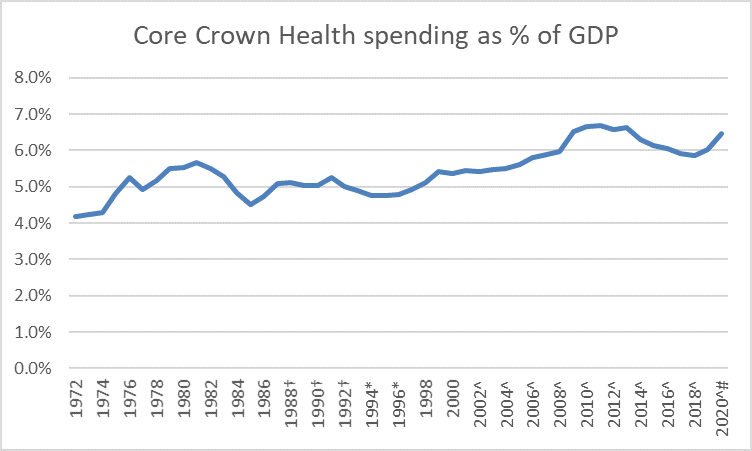

New Zealand, to the credit of politicians in both main parties, has been one of the (not so small) other group of countries where government debt as a share of GDP has been kept fairly low and fairly stable. We’ve had recessions and earthquakes, and governments with big spending ambitions but if you reckon – as I do – that low and fairly stable government debt is generally a “good thing”, New Zealand has been a success story. We even ramped up the NZS eligibility age from 60 to 65 (back to the 1898 eligibility age) in fairly short order. For good or ill – and no doubt there is an argument to be had – government health spending as a share of GDP was not much higher last year than it was 40 years ago (recall, 40 years is the statutory timeframe for long-term fiscal statements).

At the start of last year I’d probably have put myself in the camp of those saying “we’ve done okay on fiscal management and there is no obvious reason to suppose we won’t adjust as required in future”. Among other things, there is a certain absurdity in paying out a universal state welfare benefit to everyone at 65 as an ever-increasing share of those 65+ are still in the workforce, so change was likely to happen – it had in other countries, it had here previously and actually Labour in 2014 and National in 2017 and 2020 had campaigned on beginning to raise the age of eligibility (to which you might respond that none of those parties then got elected, but National still won 44.4 per cent of the vote in 2017).

I’m no longer so sure.

One chart that didn’t feature in the draft long-term fiscal report was this one from the Budget.

On their own numbers and estimates, the cyclically-adjusted primary deficit for the current (2021/22) financial year is projected to be really large (in excess of 5 per cent of GDP), at a time when – again on their own numbers – the economy is more or less back to full employment, with an output gap estimate close to zero. Note (again) that this is not a dispute about appropriate policy in the June quarter of last year when most of us were ordered to stay home and many were unable to work. It is about now.

In their text, Treasury is at pains to play down the current fiscal situation. They don’t mention these cyclically-adjusted estimates, but they claim that the situation is temporary, the spending is temporary, and will go away quite quickly. Of course, they have lines on a graph that show such an outcome, but that isn’t the same thing as hard fiscal choices over a succession of years. No doubt there are still some temporary programmes – the subsidies for Air New Zealand and exporters, MIQ costs, and vaccine costs – but a cyclically-adjusted primary deficit in excess of 5 per cent of GDP is getting on for a gap of $20 billion per annum. And every instinct of this government appears to be to spend more.

Here is the chart from the draft report

The primary deficit for 2060 on this scenario actually isn’t much larger than the primary deficit The Treasury smiles benignly on this year (assuming it will all go away quite easily). There are long-term issues that need addressing, but perhaps a less complacent approach to the current situation – and the poor quality of a lot of the new spending decisions – might be a better place to start.

Ah, but of course we heard from The Treasury a couple of weeks ago – the Secretary no less – that they are now keener on more government debt and a more active use of fiscal policy. Which probably isn’t the best backdrop against which to make the case for adjustment.

More generally, one of the things that has shifted over the last couple of years – and certainly since the 2016 LTFS – is some sense, especially on the left, that lots more public debt is something to embraced or welcomed, coming at little or no cost (so it is claimed). The focus is always on interest rates (low) and never on opportunity cost (when the coercive power of the state is at work in the spending choices). It makes it a bit harder to mount fiscal arguments about NZS if – as is probably the case – New Zealand could have government debt of 177 per cent of GDP without being cut out of funding markets (although note that, in the nature of such scenarios, the debt ratios mechanically explode beyond that 40 year horizon). And that is another reason why I’m sceptical of the benefits of reports like this: The Treasury really can’t offer any useful insights on the appropriate level of public debt, even if they can offer useful technical advice on the implications of various specific measures that might raise or lower the debt. The real debates to be had are political – both about the debt and the numerous progammes and even (to some extent) around the tax choices.

On NZS here were my thoughts from a post a couple of years ago (emphasis added)

As for NZS itself, personally I’m not overly interested in arguing the case for reform on fiscal grounds but on a rather more moral ground. Even if we could afford it, even if there were no productive costs from the deadweight costs of the associated taxes, there just seems something wrong to me in providing a universal liveable income to every person aged 65 or over (subject only to undemanding residence requirements). 45 per cent of those 65-69 are now in the labour force – suggesting they are physically able to work – which is substantially greater than the 30 per cent of those aged 60-64 who were in the labour force 30 years ago when NZS eligibility was at age 60.

I don’t consider myself a welfare hardliner. I think society should treat quite generously those genuinely unable to work, especially those who find themselves in that position unforeseeably. Old age isn’t one of those (unforeseeable) conditions, but personally, I have no particular problem with something like the current flat rate of NZS, or even of indexing it to wage movements (which would be likely to happen over time anytime, whether it was the formal mechanism from year to year), from some age where we can generally agree a large proportion of the population might not be able to hold down much of a job. I don’t have a problem with not being overly demanding in tests for those finding work increasingly physically difficult beyond, say, 60. But what is right or fair about a universal flat rate paid – by the rest of the population – to a group where almost half are working anyway? It is why I would favour raising the NZS age to, say, 68 now (in pretty short order) and then indexing the age in line with further improvements in life expectancy, and I’d favour that approach even if long-term fiscal forecasts showed large surpluses for decades to come. At the margin, I’d reinforce that policy change with a provision that you have to have lived in New Zealand for 30 years after age 20 to be eligible for full NZS (a pro-rated payment for people with, say, between 10 and 30 years of actual residence). Why? Because in general you should only be expected to be supported by the people of New Zealand, unconditionally, in your old age, if most of your adult life was spent as part of this society.

Reasonable people can, of course, debate these suggestions. But they are where I think the debate should be – about what sort of society we should be, what sort of mix between self-reliance and public provision there should be, even about what mix of family support and public support there should be, or what (if any) stigma should attach to be funded by the taxpayer in old age – not, mostly, about long-term fiscal forecasts.

And Treasury can’t help with very much of that. It is what we have politicians, think tanks, and citizens for.

I don’t think enough weight is given to the role that rules of thumb play in disciplining choices. If, in modern floating exchange rate open-capital account economy, many governments can take on almost any amount of debt as they want, and even the interest rate consequences of higher public debt are really quite small, what constrains government choices? No doubt there are a few zealots who think no constraints are necessary, but most people – left, right, or centre – don’t operate that way.

I favour running fiscal policy to two rules of thumb (not legal restrictions, but political covenants/commitments). First, aim to keep the (cyclically-adjusted) operating balance near zero, and second, aim to keep net public debt (all inclusive measures) near zero.

Note that (a) neither rule of thumb would be binding year by year (the state needs to cope with pandemics, earthquakes, or the like), they would be constant aiming points, the standard reference points towards which policy is oriented over several years, and (b) neither rule of thumb says anything about the appropriate size of government (if we conclude we want governments to do more (less) longer-term than adjust tax rates to pay for that. Adjusting tax rates – especially upwards – is a much higher hurdle (and appropriately so) than the Cabinet (commanding a majority in Parliament) simply deciding one morning to substantially alter spending.

There is probably less dispute about the operating balance rule of thumb than about the debt one. Smart people will mount arguments about (a) infrastructure, or (b) the potential capacity of the Crown to capture various high returns. A typical householder or company will, after all, have some debt. But (a) the disciplines on individuals and firms are much stronger, and more internalised, than they are for governments, and (b) much of government activity acts to reduce private savings. I’m not going to pretend there is any great difference between the narrow economics of a 20% debt target vs a -20% one, but zero has a resonance that no other number is ever likely to have. (And if you think this benchmark is demanding, on my preferred analytical measure – the OECD series on net general government financial liabilities – New Zealand has been between 10 per cent and -5 per cent of GDP continuously since about 2004.)

If you want the state to do more, make the case, have the debate for higher taxes – which takes the resources from specific identifiable types of people (tax incidence arguments aside), rather than by monetary policy squeezing out other private sector activity to make way for the government (in a fully-employed economy they are the only two options, there are no free lunches).

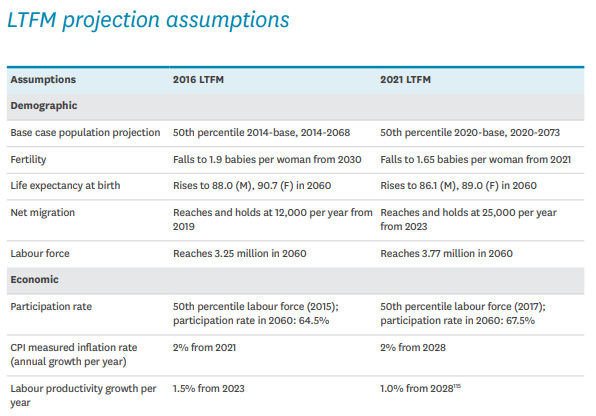

This has gotten rather rambly and I’m going to stop here, except to point you to this interesting table at the back of the Treasury report.

I noted:

- the sharp drop in the long-term assumed birth rate (largely reflecting recent developments presumably)

- the reduction in the assumed improvement in life expectancy

- the significant reduction in assumed long-term productivity growth, and – unlike the others, substantially a policy matter,

- the substantial increase in the assumed long-term annual rate of net inward migration

Reblogged this on Utopia, you are standing in it!.

LikeLike

In order to remain viable, one of the key restrictions to National Superannuation would be to apply it to NZ citizens only. NZ residents with overseas passports should be cut from being entitled to National Superannuation. The 10 year stand down period should also be extended to the 600k New Zealanders that live and work in Australia and have not paid any NZ taxes for most of their lives.

National Party should not be increasing the age entitlement to 67 without first cutting out the non citizens from the scheme. Why are New Zealanders being treated poorly so that other Nationalities get equal entitlements?

LikeLike

Another report. More blather posing as information. This report is merely word salad to the government of the day. A useful distraction from the never never land we are fast becoming. China won’t have to invade us we are so without any sense of reality we will probably surrender.

LikeLike