That was, more or less, the title of two events I attended at the University of Auckland last Thursday. With the help of generous funding from the Sir Douglas Myers Foundation (in particular), the university had been able to bring in a bunch of well-regarded overseas academics and prominent “public intellectuals” for several events focused on issues around the potential and actual disruption to economic globalisation as a result of overt political choices (notably, the tariff policies of recent US administrations). The key person driving the programme seems to have been Prasanna Gai, professor of macroeconomics at Auckland (and, of course, a member of the Reserve Bank Monetary Policy Committee, where he sets something of an example to his colleagues by actually being willing to deliver speeches and outline his thinking).

I gather there was a more technical academic-focused event on Friday, but the two events I attended were the full day workshop on “Geoeconomics and the Future of Globalisation”, and an evening public dialogue event “Geoeconomic Fragmentation: Challenges and Opportunities”.

The workshop was conducted on Chatham House rules so I can comment only on what was said and not who said it. Attendees were a mix of academics, market economists and the like, and public servants and people with official roles. I’m not quite sure why the presentations – mostly from academics – were non-attributable (several speakers drew on their published papers) but anyway, those were the rules.

The evening event featured two visitors, in dialogue (of sorts) moderated by Gai. The first was Andy Haldane, formerly of the Bank of England and now one of the great and good, whose op-eds on all sorts of interesting issues, and angles on those issues, pop up not infrequently in places like the Financial Times (one of those Brits you feel sure will end up with a knighthood or perhaps a peerage). And the second was Laura Alfaro, currently chief economist of the Inter-American Development Bank, on secondment from an academic position at Harvard Business School, and also a former minister in her native Costa Rica. I doubt I am seriously breaching the rules if I say that Haldane’s remarks at the evening event (see below) were very very similar to those at the earlier workshop.

The whole area of so-called geonomic fragmentation should be fascinating (indeed, one panellist went so far as to call it “the only topic”) After all, not only do we have Trump (and between his terms Biden, who didn’t exactly dismantle Trumpian protectionism from the first term), but issues around both the political and economic rise of China, the widespread use of unilateral US sanctions (a recent book on which I wrote about earlier in the year), and of course the intense efforts from some countries (including little old New Zealand) to use sanctions to put pressure on Russia and its ongoing war on Ukraine. In our own remote corner of the world, I presume New Zealand restricting aid to the Cook Islands over apparent geopolitical concerns won’t exactly be good for bilateral trade.

There were some interesting presentations. I particularly enjoyed a keynote address on global value chains and geonomics, and especially the way in which connections of individual firms are often more important to focus on than industries or countries per se (thus, the dependence of TSMC on single firms in Holland (ASML) and Germany (Zeiss)). We were also reminded that most firms that import buy a particular product from a single supplier, with little or no effective diversification, something extreme tariff uncertainty may change. This presenter also reminded us that up to 40 per cent of US trade now involves dual-use products where national security considerations can reasonably come into the mix. That lecture concluded with a reminder that trade policies will be shaped by whatever it is that governments want to maximise at a point in time, and there is no necessary reason why that goal should be maximisation of near-term GDP. National security considerations are to the fore much more than they were, or than was readily conceivable, in the 1990s and 2000s. But there was also a reminder that if private firms will never internalise all externalities, those same private firms will innovate quickly when the rules of the game change (thus China’s current chokehold on “rare earths” is unlikely to last long).

There were also useful reminders as to just how much the tariffs etc have changed trade between US and Chinese firms: China’s share of US imports has now dropped back to around where it was 20 years ago. And yet at the same time both Chinese exports and US imports in total have continued to grow. There was an argument made by several speakers that as yet there is little sign of overall globalisation having gone into reverse. In his evening address, Haldane was particularly strong on this claim, arguing that flows of goods, and people, and money (and even more so information) are at levels never before seen, and (more ambitiously) that the benefits of these flows were at least as large as economists like him had argued for (I was curious where he was going to find the evidence of the economic benefits of large scale immigration to his own country, it of the underperforming economy, but no one asked). Haldane argued that much of what was wrong with political tides, public mood etc, was that economists had underestimated the social and redistributive effects of globalisation. Count me rather sceptical, but Haldane – a technocratic social democrat – saw it as grounds for more and smarter government, to enable people to reskill, retrain etc. He was also openly championing industry policy – seeming to conflate legitimate national security issues with the rather more dubious of politicians and officials trying to pick winners (and wasn’t even that compelling on the national securituy side in suggesting a place for food protectionism). And if he was overall optimistic (self-described) he still saw risks of all falling apart, an unravelling of open trade, and risks around a crisis over high and rising public debt. Quite what the latter had to do with geoeconomics wasn’t clear to me.

Haldane was a funny mix. He seemed keen on international financial institutions leading the public dialogue on the benefits of globalisation (as if such agencies – IMF etc – commanded mass public trust…..), and also called on business to play a more prominent role (good luck with that). But when asked about the role of technical experts I thought he was to the point in asserting that they need to wear lightly what expertise they have, and be much more willing to own up to mistakes (“we all make them after all”). I don’t recall if he mentioned them specifically, but central banks seemed to be among those he had in mind. If you like citizen panels to deliberate on policy issues, Haldane too was keen. Quite what it had to do with the geoeconomic challenges wasn’t quite clear, although I think that he, like some other participants, were inclined to aa view that if only the public were made to see what was good for them normal service could be resumed (one speaker at the workshop was robustly, but shallowly, of that view regarding mass immigration). Quite how it took account of the activities of places like Russia and China wasn’t clear.

Of the evening speakers, I found Alfaro (from the IADB) much the more interesting, partly presenting work she’d done for a Jackson Hole paper a couple of years ago and in pushing back on some of Haldane’s enthusiasms (industry policy for example). Like many speakers she noted that the US protectionism was unlikely to dissipate quickly – that the political environment had changed, and that little about that was unique to Trump. She reported some results in which public respondents were very sceptical on trade, and retained that scepticism even when presented with apparently hard evidence of the benefits. She stressed the decoupling of trade between the US and China, but also argued that so far that had proceeded smoothly, often supported by banks to enable firms to reallocate business, and that there was little evidence of overall deglobalisation. As for whether the vaunted “rules-based-order” could re-establish itself, she placed considerable weight on the willingness, or otherwise, of the US to assume leadership in a multilateral context. I got the impression she was not optimistic.

There was quite a strong sense from speakers of hankering for a better time (perhaps 15-20 years ago). I was less convinced that this particular group of speakers had much to offer in thinking through the economics of geopolitics and associated fragmentation issues. No doubt they were experts in their own narrow fields, but perhaps those were more about “what are the effects and where do they show up” (interesting in its own right) rather than in how best, and when, to deploy economic policy instruments. China itself attracted very little attention – whether for example modern slavery issues and associated restrictions, political interference, alliance with Russia, threat to Taiwan, or whatever. Politics – geopolitics especially – just wasn’t the comfortable place for most of these presenters.

One speaker – who has a lot of published material in this area – was among those emphasising a standard result that if, say, the US imposes large tariffs on other countries they should not retaliate as doing so would only make the retaliating country poorer. On the assumptions in the model, of course that is sensible – overall, the cost of trade protection are mostly and ultimately borne by consumers in the country imposing the restrictions. But one of those assumptions – in fact a critical one – seems to be that trade policy retaliation does not then change, for the better, the behaviour of the original protectionist power. But there was no analysis of when and whether that might, or might not, hold. Alliances were mentioned a few times during the day, but never very systematically. One of the things that was striking to me back in March/April was the way countries seemed to make no effort at all to work together to push back on the rogue actor in Washington (in our part of the world, for example, Luxon and Albanese offered no vocal support to the Canadians). I have no idea whether a more concerted effort might have deflected Trump (perhaps it would have worsened things) but you might have hoped for more analysis of the issue.

It is easy for economists to simple wish that politics would stay out of the way, and derive results that assume it away. It is also easy to focus on GDP maximisation (or some less crude utility form of that), but – as above – much depends on what politicians actually want to maximise. No doubt modellers in August 1939 would have told us that retaliating against the next German aggression would only make us poorer – and of course, it did so dramatically, as massive cost of blood and treasure – but a handful of courageous countries (Britain, France, New Zealand, Australia, Canada, South Africa) concluded that it was a price worth paying for a better, but risky, outcome. No doubt when China invades Taiwan, modellers – and firms – will produce results showing that retaliation will only make the rest of us poorer. No doubt, but do we just sit by? Most of the West has chosen not to in respect of Russia even when, as in the New Zealand or Australian case, Russia poses little or no direct threat to us. In my view, we were right to do so. And then of course, which instruments work best, which risk being self-liquidating (eg concerns about US overuse of unilateral sanctions motivating innovative to reduce that exposure).

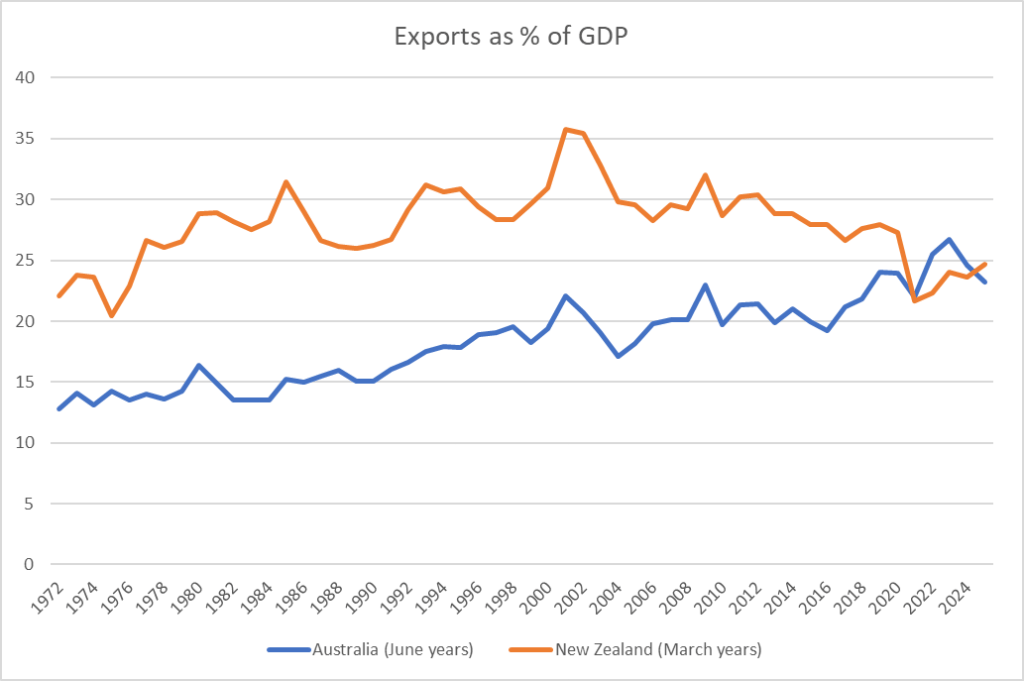

Finally, there was quite a strong sense that the workshop and dialogue were quite northern hemisphere focused. Amid all the upbeat reminders about the ongoing reach of globalisation I don’t recall anyone all day pointing out that, at least on trade in goods and services, globalisation in New Zealand has been going backwards for 20 years now, without anyone even consciously trying.

Lest I sound unduly negative, I enjoyed the day, caught up with people I hadn’t seen for a while, and appreciated the invitation. And surely the benefit of events like these is if attendees coming away thinking a bit deeper or broader themselves, even if a little orthogonally to the actual papers presented.