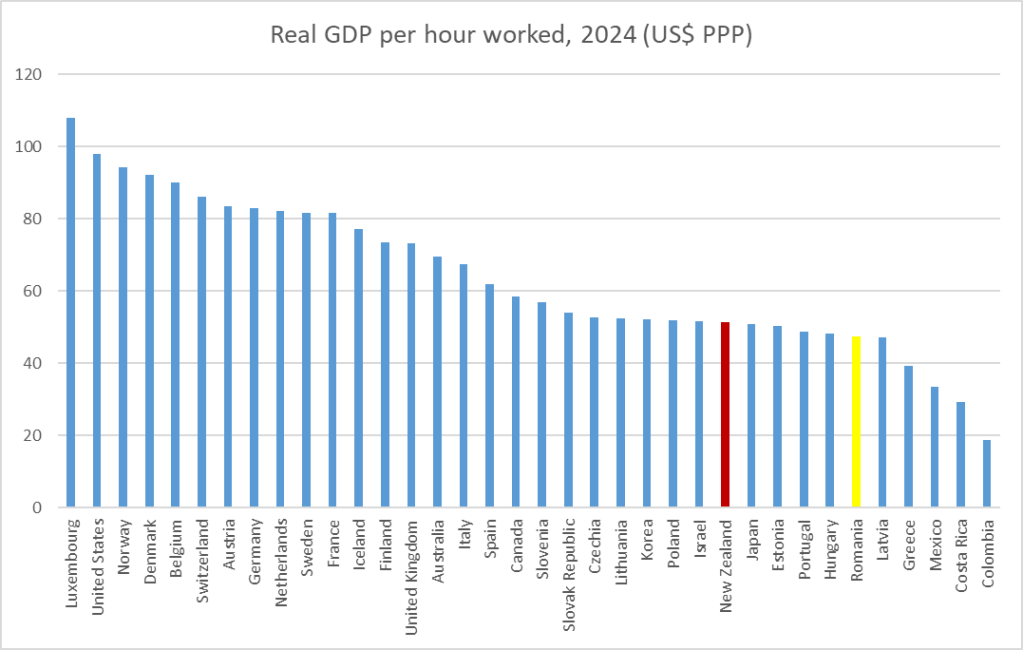

Over the life of this blog there have been a few charts I’ve kept coming back to. There have been some of the obvious ones, for example around the persistent underperformance of the New Zealand economy on labour productivity. It takes a while for a fairly annual data to turn up on the OECD database, but here are the near-complete 2024 estimates.

Just two observations on that chart:

First, it would take a 74 per cent increase in average labour productivity in New Zealand to match the average across Denmark, Belgium, and Switzerland (3 small European countries, not heavily reliant on nature’s bounty – unlike, notably, Norway). That margin – the steep hill we have to climb – has slightly increased in the last decade.

Second, Romania isn’t in the OECD but back in 2017 I wrote a long post about Romania and suggested then that if the relative performance of productivity growth in the two countries over the previous decade continued in another 20 years they’d have caught us (the backdrop of course being the absolute mayhem left at the end of the Ceaucescu regime). On present trends now (last decade’s performance), Romania is likely to pass us in perhaps another five years.

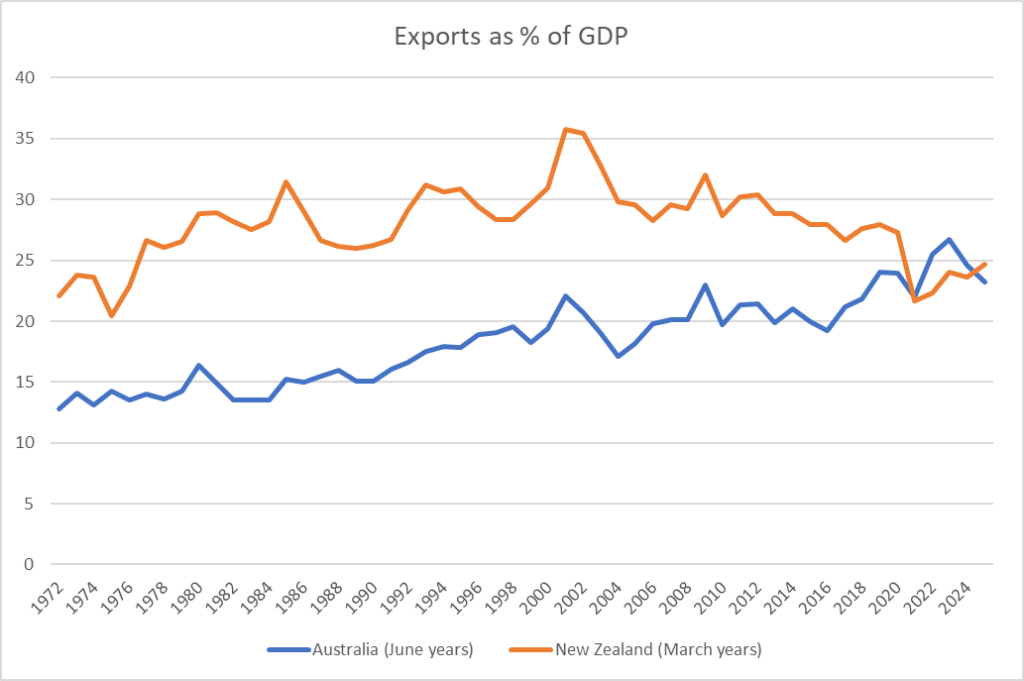

Then there were the foreign trade charts I updated in a post last week.

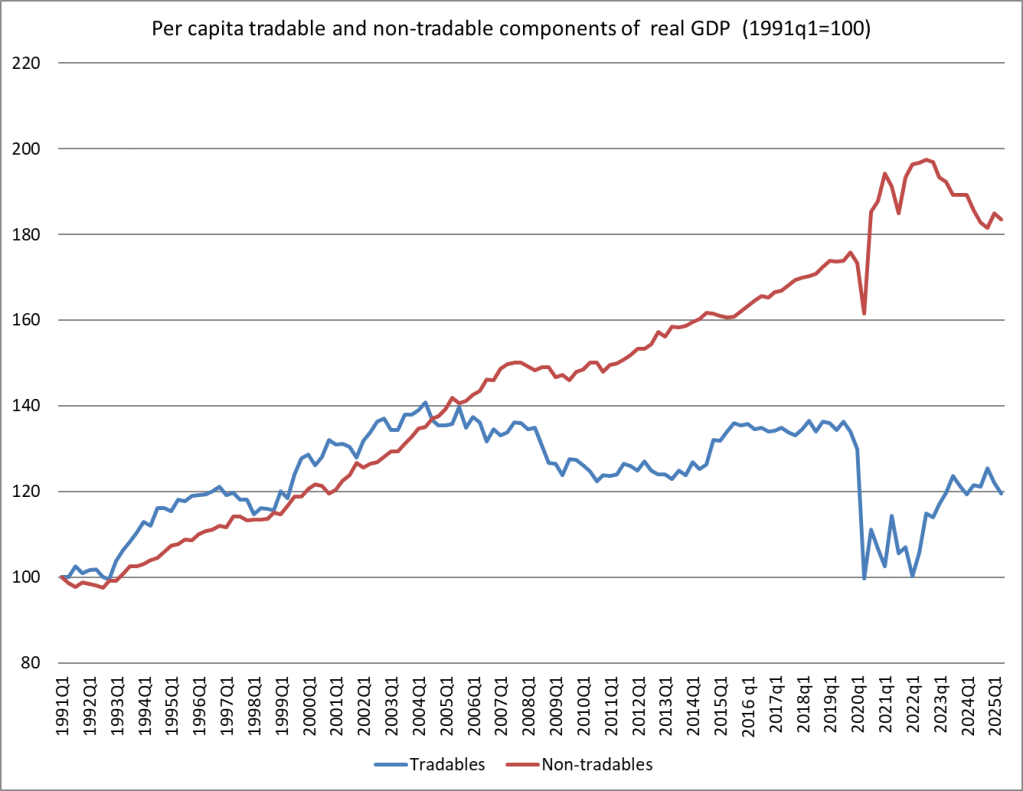

In a somewhat related vein, every so often I’ve run a chart (first devised for New Zealand by the IMF) that is a rough and ready indicator of the split between the tradables and non-tradables parts of our economy (tradables here being the primary and manufacturing sector, together with exports of services).

This is the latest version

The dismal nature of the picture (and economy) is captured in that blue line. Not only has the pre-Covid level not been regained, but the per capita size of the tradables sector of our economy is way smaller than it was 20 years ago. Meanwhile, the non-tradables sector, after a Covid and overheated domestic economy interruption, seems to keep tracking upwards. It isn’t a sign of a healthy economy.

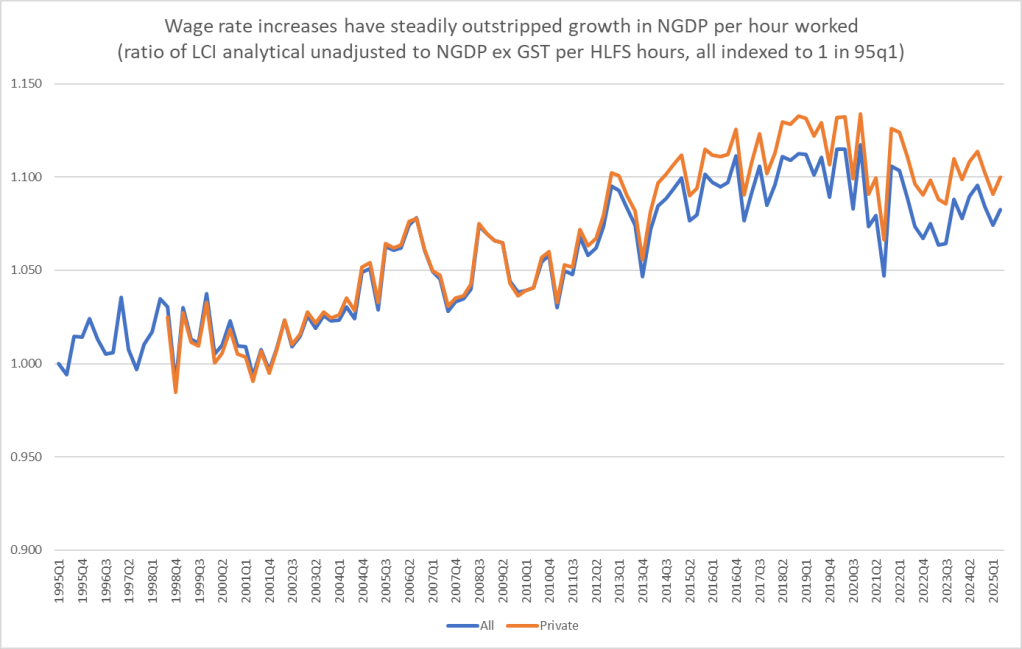

And finally in this brief update post, what about wages? Every so often I’ve included this chart.

People don’t seem to find it very intuitive, but when the lines are going up wage rates (captured by the LCI analytical unadjusted series) are rising faster than nominal GDP per hour worked. When I first did the chart, perhaps seven or eight years ago, of course what caught my eye was the (quite strong) upward trend over 15+ years from about 2000. I saw it as another way of casting light on real exchange rate or competitiveness issues, and as not inconsistent with the inward skew to the economy apparent in the previous (tradables vs non-tradables) chart. Whatever the causes, relative to the capacity of the overall economy to pay (or generate income), wage rates were holding up strongly.

The series is noisy (terms of trade fluctuate quite a bit, and the hours worked series is also a bit noisy quarter to quarter). But there is also no mistaking that the trend apparent up to the late 2010s, arguably right up to the eve of Covid, has changed since. Wages have actual fallen back relative to nominal GDP, whether on the private sector or whole economy wage measure. (And for those who insist on a partisan lens, it doesn’t appear to be a Labour vs National thing.) The fall back isn’t large, absolutely or relative to the previous rise, but equally it isn’t inconsistent with all those polls suggesting that “cost of living” is still the most front-of-mind public concern.

There is no overall intende message in this post, just that coming towards the end of another year it is worth standing back and reflecting on the more structural aspects of how the New Zealand economy is doing (there will always be cyclical swings). In summary, not well.

UPDATE:

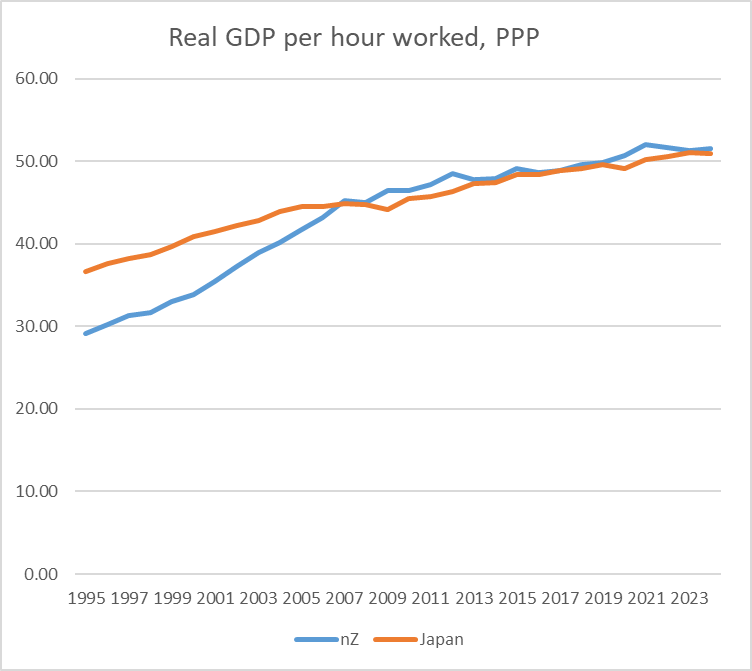

A commenter noted that in the first chart above NZ was just ahead of Japan. On this measure, we have been much the same as Japan for getting on for 20 years now.

Apart from Romania being likely to overtake us, the other real surprise is that Japan is just below us on the real GDP/hour measure……

LikeLiked by 1 person

I added a chart to the post illustrating that (on this measure) we caught up with Japan almost 20 years ago now and have basically been level-pegging since.

LikeLike

I have worked in the private sector my whole life. I have seen continual efficiency gains and/or increasing sales (volume and price) without a 1:1 labour input effect. So where does our productivity fall down? Is it a public sector/private sector issue?

The current deindustrialisation that is happening due energy related decarbonisation costs is going to make your graphs look pretty sick in the next few years.

LikeLike

It mostly isn’t a public /private issue (public sector productivity is an issue in most places). More about the failure of firms operating here to successful find overseas markets for more products/services, in turn a reflection of distance (which we can’t do much about) and a persistently overvalued rap exchange rate.

LikeLike

Interesting. If it is a real exchange rate issue, ie the nominal and as a consequence real exchange rate need to be lower to increase exports, then does that suggest that we are over populated relative to our productive capacity? If the real exchange rate was lower then I would expect an exodus of human capital as it is relatively easy to arbitrage the real value effects.

LikeLike

The essence of the story I’ve running for 10-15 years now is that high rates of immigration to a country with relatively limited oppprtunities (distance etc) and modest savings rates has turned the economy inwards, channelled by an overvalued real exchange rate (thst fluctuates but which in trend terms has not enduringly fallen as NZ productivity dropped so far behind OECD leaders). A material change in immigration policy would work in part by lowering the real exch rate.

LikeLike

Hi, thanks for that. I went to look at permanent net migration and found the series ended in Nov 2018. I have not managed to work out the relationship between the new estimated data and the old arrivals and departures data. I was looking to see if there was anything that “happened” around the 2005/7 GDP per hour worked inflexion point.

There is definitely a ramp up in net migration from 2001 and another lift in 2014.

Are we predominantly “importing” people to undertake domestic economic activities?

LikeLike

Remember that global (advanced world) prodiuctivity growth also slowed down markedly after 2005, so a date like that may not be critical to the NZ specific element of the story. It isn’t so much that the non-citizen migrants are coming to one sector vs another as that bringing a lot more people in tends to skew the economy inwards partly to meet the (wholly legitimate) needs of the migrants (houses, schools, roads, factories, shops, offices etc).

LikeLike