I’ve never really been persuaded that it is a good idea for public servants to be giving speeches, unless perhaps they are simply and explicitly explaining or articulating government policy. If they are, instead, purporting to run their own views or those of their agency it is almost inevitable that we will be getting less than the unvarnished picture and more than a few convenient omissions. Public servants still have to work with current ministers after all.

The thought came to mind again when I read a speech given last week by Struan Little, now a “chief strategist” at the Treasury but until recently a senior Deputy Secretary (and actually Acting Secretary for a time last year). The speech was to some accountants’ tax conference, under the heading “The role of the tax system in addressing New Zealand’s intertwined fiscal and economic challenges”. All else equal, you might suppose that lower taxes would be more likely to be part of dealing with the productivity failings and perhaps higher taxes might have some role to play in closing the gaping fiscal gaps. It isn’t clear that Treasury necessarily sees it that way. They seem quite keen on raising taxes generally, especially on returns to capital.

(To be clear, I’ve been on record for some time picking that whoever is in government over the next few years the GST rate will rise, but that is prediction not prescription – and I’m not a senior official. Somewhat oddly, in his speech Little claims that “there are no simple options to raise substantial merit over the shorter term” when, whatever the merits of such a policy, raising GST is certainly simple.)

Now, I guess it was a tax conference, but it was slightly odd that not even once was it mentioned how much spending has increased in the last few years. Core Crown operating expenses were 28 per cent of GDP in the last full pre-Covid year (to June 2019) and in this budget were projected to be 32.9 per cent of GDP this year (25/26), slightly UP on last year. The current structural deficit, from the same budget documents, was projected to be about 2 per cent of GDP. I guess officials always need to have tools to hand if politicians want to go the higher tax route but it isn’t obvious that the scope of expenditure savings has been exhausted (or even much begun perhaps outside core departmental operating costs, which generally isn’t where the big money is).

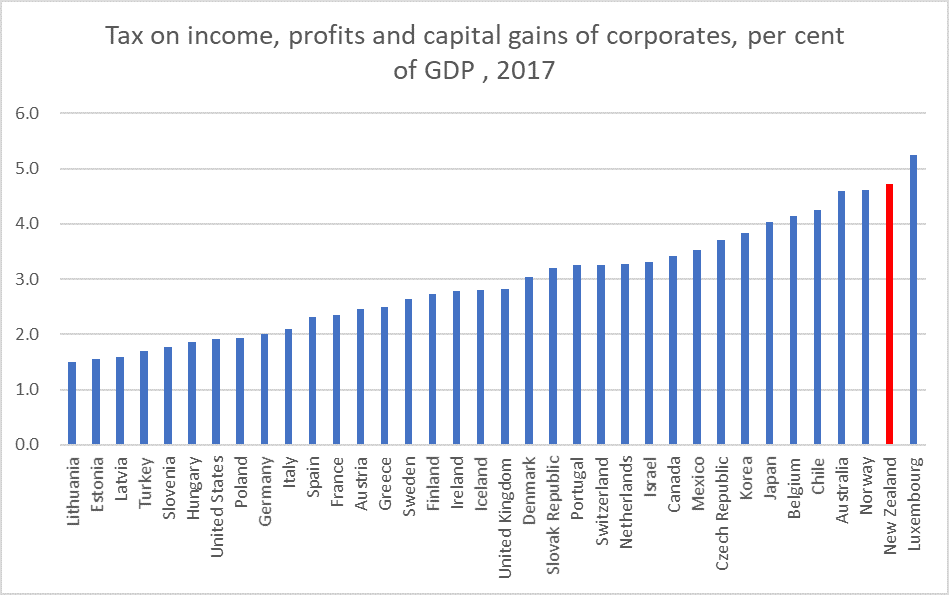

Remarkably also, there is no mention at all in the speech that New Zealand’s company tax rate is among the highest in OECD countries. In the literature, the real economic costs of company taxes are generally found to far exceed those of other main types of tax. There is no mention either that New Zealand has long taken one of the highest shares of GDP in corporate tax revenue.

That chart is a few years old now but the OECD data are very dated and the most recent I could find on a quick search was for 2020 (when, unsurprisingly, we would still have been well to the right on this chart).

Instead what we got is a straw man discussion, claiming that life (and literature) have moved on and that now everyone agrees the tax rate on returns to capital should be positive. In practice no one has seriously argued in the New Zealand debate that capital income should generally be taxed at zero, notwithstanding some literature suggesting that on certain assumptions a zero rate might be optimal. Where there is debate is a) how high that rate should be, and b) what should count as taxable (capital) income.

Now, to be fair, on a couple of occasions Little suggests that we need to cut taxation on returns to inward foreign investment (because of our imputation system the company tax rate falls most directly on foreign investors), but then never addresses the issue as to whether or why our income tax regime should treat foreign investors more favourably than domestic investors and what the implications of that might be.

Treasury has, of course, long been keen on the idea of a capital gains tax. Little repeats an estimate from the Tax Working Group some years ago suggesting that such a tax might raise 1.2 per cent of GDP per annum but then never bothers engaging with the fact that the largest source of (real) capital gains in recent decades has been in housing, and that the reform programme of the current government is supposed, at least according to the Minister responsible (if not to his boss) to be lowering house prices, and (presumably) making sustained and systematic real capital gains on housing/land a thing of the past.

Little champions the somewhat-strange Investment Boost subsidy introduced in this year’s Budget, and yet (of course) never notes that the biggest returns (by a considerable margin) to that subsidy are for investment in new commercial buildings. The very same sector that the government (perhaps over Treasury objections) increased taxes on last year, when it barred tax depreciation on commercial buildings. Where is the coherence in that? Or in the fact that Investment Boost offers a subsidy to rest home operators but not to providers of rental accommodation? But I guess Treasury wouldn’t really want to comment in public on any of that. The Minister would certainly not have been keen on them doing so. He never offers any thoughts either on why subsidising a specific input – as if capital goods are some sort of merit good – is preferable to lowering the tax rate on returns to whatever combination of inputs firms find most profit-maximising.

We also get the same (now decades-old) line about housing being tax-favoured while never noting either a) that the story of New Zealand in recent decades has been too little housing (& urban land) not too much, or b) that the largest tax advantage by far in respect of housing is to the owner-occupiers with no debt. Perhaps Treasury favours taxing imputed rents (with suitable deductions including for mortgage interest) but if so there is no hint of it in the speech (something for which the Minister would no doubt be grateful).

And there are tantalising but concerning lines suggesting Treasury might favour rather arbitrary distinctions between returns to different types of capital. Thus, there is mention late in the speech of possibly in future reducing tax on “productive capital investment” (which then does Treasury regard as “unproductive” ex ante), there is a reference at one point to taxation on “physical capital”, without being clear as to why physical capital returns should be treated differently than returns on intangible capital. And perhaps potentially most concerningly there was this line: “a coherent approach would not necessarily mean taxing all capital [returns to capital?] at the same rate, since not all capital is the same”. What, one wonders, does Treasury have in mind there? After all, not all human capital is the same either (you are different than me) but our tax system treats all financial returns to it much the same anyway (or so it seems to me; perhaps I’m missing something).

There are some fair points in the speech. Little notes that our system “penalises certain types of saving when inflation is high”, which is true but understates the point: even 2 per cent inflation results in such distortions, and they apply to borrowing (when interest is deductible, which it generally is for business) and depreciation, not just to returns on fixed interest assets. These distortions have been known for many decades, and yet there seems to be no momentum – political or bureaucratic – to address them, whether by changes to the tax system or to the inflation target.

And there was a paragraph late in the speech that I very much welcomed.

I’ve long been keen on a Nordic approach and it was an option noted by the 2025 Taskforce back in 2009. But what chance is there that the bureaucrats might support such a change? When I was involved in tax debates IRD was quite resistant to any cuts to business tax rates arguing (with little or no evidence) that many taxable profits were rents – returns above the cost of capital – and that taxing them came at little or no cost. And if by some chance a new generation of officials has emerged, what chance ministers (whichever main party is in government) being that bold. Another growth-supportive option that might have warranted mention in that paragraph would have been work on the possibility of a progressive consumption tax.

As I noted at the start of the post, I’m not sure senior officials really should be making speeches other than to represent the policy of the government of the day. They simply can’t add much, or any sort of unconstrained perspective. The free and frank advice has to be for ministers. That said, perhaps at some point it would be useful for Treasury to publish some research/analysis outlining what sort of tax structure would, in its view, be most conducive to supporting a much faster rate of productivity growth in New Zealand. It is unlikely that tax system changes could ever represent any sort of panacea but insights into the mental models of the government’s premier economic advisers could still be useful. Since it isn’t impossible that the answer might be much lower taxes (and thus spending) than at present, you could even put some constraints around the exercise: if you (or your political master) needed to raise 27 per cent of GDP in tax, which mix of taxes and tax rates would be most consistent with helping enable a materially faster rate of productivity growth.

Good post. The term “productive capital” needs to be relegated to the dustbin of history. It is a wholly nonsense phrase that people hide behind to push whatever agenda they want.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Like many Wellington once great instititions (like the RBNZ), the Treasury is a shadow of its former self. Low quality staff. Hopeless senior management team. I visited there many years ago with Sir Roger Douglas to meet Treasury Secretary Makhlouf. Half an hour before he said he couldn’t make the meeting anymore. So I told him we couldn’t make it either. Then ten minutes later he called to say he could make it. The meeting was a waste of our time. The senior managers we met barely knew any economics.

On that note, Little’s speech was a load of hogwash. Changing the tax mix is very much a side issue compared to others like the fiscal blowouts that have been forecast due to population ageing and the state of our health service. Best Treasury staffers don’t make public talks when its all wrong, confused and they’re insufficiently qualified. Its a new world. The game has changed. Willis, Lux and Little types are out of touch. Its not 1970.

LikeLike

Michael

You raise an interesting point about the compatibility of a high corporate tax rate and CGT. But everything about particular taxes has plus/minus. Be that a tax on consumption (GST), income (PAYE and corporate), capital gains (company, individual), capital (rates), or targeted (alcohol, fuel, tobacco).

Its a real shame that we dont (so far as I know) have a document that outlines the pros/cons. The consequence is that politicians and “experts” pop up with their views and the rest of us are left scrambling. The current CGT “debate” is a good example. A massively complex and distortionary tax that plays to a desire to “eat the rich”, or a fair treatment of a form of income which is currently not paying its share? Take your pick.

Obviously something has to happen to address government’s deficit as the current levels of borrowing are already impacting the cost of funds and that can only get worse. Plan A seems to be “growth” so there is more to tax and user pays (water and roads). Which implies that new/higher taxes are perceived as largely political.

Tim

LikeLike

There are certainly gaps in the material that is out there. Small country problem I suppose, at least in part (no specialist tax think tanks etc and few detached academics in the area).

On growth, important (crucial) as it is, I suspect few economists etc believe it is any sort of panacea for the worsening fiscal imbalances. There will need to be hard choices on spending and/or tax policies as well.

LikeLike